THE NEW URBAN DESIGN – A SOCIAL THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE ?

on

RUANG

SPACE

THE NEW URBAN DESIGN – A SOCIAL THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE?

By: Alexander R. Cuthbert1

Abstract

Over the last ten years and 1000 pages of text, I outlined a unified field theory which I refer to as The New Urban Design. Possessing the same structure, the three books can be read in series or in parallel, and may best be described as a matrix of possibilities (Cuthbert 2003, 2006, 2011). In this paper I revisit some of the ideas in these texts that need to be more fully developed. Important among them are the undeniable effects of this new field for architecture and urban planning, and an expanded brief on the use of Marxian modes of production to support social analysis in these disciplines. From this perspective we can at least develop some truth as to the historical progress of urban form. In redefining urban design as an independent field, architecture and urban planning subsequently become different regions of thought from what they had previously entertained, namely during the period when they colonised urban design and shared the spoils between them. Extending this argument even further, it is clear that neither discipline, nor the resulting mainstream urban design (i.e. one produced by architects and planners) - have had resort to a social theory of their own existence. All so called theories of architecture and urban planning, have failed with good reason. Architecture has relied almost exclusively on aesthetics and technology for its self awareness. Despite the fact that social theory began to penetrate planning theory in the 1970’s, this did not change the idea that planning can have no internally generated theory other than the trivial, since it is an epiphenomenon of the state. It is not an independent factor in urbanisation, and therefore can have no consciousness of its own that is any more than ideological in the Marxist use of the term. In conclusion, the paper suggests that if the weltanshuung of the New Urban Design is persuasive, this has wide ranging implications for education, practice and the development process at all scales of operation.

Keywords: urban design, social theory, mainstream logic, ideology

Abstrak

Dalam sepuluh tahun terakhir penulis telah memaparkan sebuah kesatuan teori yang direpresentasikan ke dalam 1000 halaman tulisan (tiga buku), yang Penulis pandang sebagai The New Urban Design. Dengan menerapkan struktur yang baru, ketiga buku ini bisa dibaca secara beruntun (seri) maupun secara pararel, dan juga bisa dideskripsikan sebagai matrik yang menawarkan beragam kemungkinan (Cuthbert 2003, 2006, 2011). Dalam paper ini, Penulis meninjau kembali beberapa ide terkait, yang perlu dikaji lebih lanjut. Beberapa hal penting yang perlu digarisbawahi disini adalah, dampak dari kemunculan bidang urban design yang tidak bisa dihindari terhadap dunia kearsitekturan dan urban planning, dan pengenalan lebih lanjut dari penerapan moda-moda produksi sesuai konsepsi Marxisme dalam mendukung analisis sosial berkenaan kedua disiplin ini. Dari perspektif ini, kita, paling tidak bisa membangun kebenaran akan kemajuan historis dari sebuah tatanan perkotaan. Dalam meredefinisikan urban design sebagai disiplin yang independan, arsitektur dan urban planning selanjutnya menjadi bidang yang berbeda dibanding dengan pemahaman kita sebelumnya. Khususnya pada masa-masa dimana-

arsitektur dan urban planning mendominasi urban design. Melanjutkan argumentasi ini, urban design secara umum (yang didefinisikan oleh para arsitek maupun urban planner) belum memiliki teori-teori sosial yang dibangun berdasarkan keberadaannya. Semua yang disebut dengan teori tentang arsitektur ataupun urban planning telah gagal untuk alasan-alasan tertentu. Arsitektur secara ekslusif bersandar pada estetika dan teknologi untuk kebangkitannya. Meskipun dalam kenyataannya teori-teori sosial telah pada awalnya mempenetrasi teori tentang planning di tahun 1970's, ini tidak merubah ide bahwa planning belum memiliki kemampuan untuk membangun teorinya sendiri secara internal. Ini dikarenakan oleh perencanaan sebagai sebuah epiphenomenon dari negara. Ini bukan faktor independan dalam pertumbuhan sebuah kota, dan sehingga bisa memiliki kesadaran dari dirinya sendiri yang melebihi ideologi dalam konteks pemikiran Marxisme. Sebagai kesimpulan paper ini menyarankan bahwa, jika perspektif dari new urban design sangat persuasif, ini memiliki implikasi terhadap pendidikan, praktek dan proses pembangunan pada beragam skala dan operasionalnya.

Kata kunci: perancangan kota, teori sosial, logika, ideologi

Introduction

" It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness" (Marx: A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy).

" Human beings are not a species that are content to live in society, but a species which produces society in order to live – in other words [one which] invents new modes of organisation and thought" (Maurice Godelier: The Mental and the Material).

The private realm of architecture and the public realm of urban space require to be interpreted not in their own terms but in terms of urban design. But this is not the old or mainstream urban design of architecture to which I refer. Rather it is a new sense of urban design that is evolving, one with a global compass, whose object is the form of cities, not merely architectural projects. Urban design is not a concept universally deployed in all countries, and the meanings attached to it vary enormously. In 1953, the Spanish architect Jose Luis Sert first defined urban design as project design (Cuthbert 2009, Krieger 2009). Given the state of knowledge at that time within the environmental professions, this seems quite reasonable.

On the other hand that definition has endured over the last sixty years and still retains great influence. Sert defined what he considered to be urban design purely on his own opinion and in the absence of any refined understanding of the structures that govern society and space. On reflection his action was more a need to monopolise territory focussed on constructing projects in the aftermath of World War II, than to arrive at a scientific definition of a discipline. So Sert actually set constraints on the field of urban design by conflating it to project design, a situation from which it is still struggling to recover.

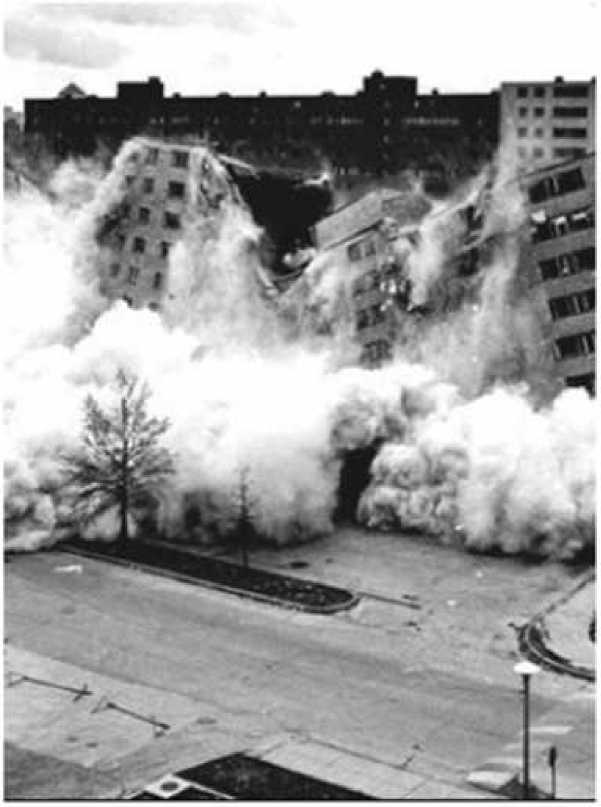

The pitfalls in this definition are legion. First, there are the incredible limitations of Sert’s position - how do we explain the forms of global urbanisation that cannot be reduced to a project? (Figure 1). Second, if we look at historical cities such as Shishtar, can there be any serious suggestion that this magnificent creation has no urban design qualities since it is not a project? (Figure 2). Third, do many of the astounding failures of mainstream urban design still qualify as ‘urban design,’ for example the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St Louis designed by world famous architect Minoru Yamasaki (the project had to be dynamited due to insoluble social problems (Figure 3)); the Gorbals in Glasgow, or indeed the centres of many American cities today? Fourth, to this we can add the indulgences of the architectural imagination that created monsters in the name of urban design, and which thankfully were never built (for example le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris, and Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Hochhausstadt Project of 1924).

Figure 1. Fort Worth Texas 1970 Source: Author

Figure 2. Shishtar Iran

Source: Kostoff (1992:221)

Figure 3. Pruitt-Igoe St Louis

Source: https://www.google.com/search?q=pruittigoe+housing+ project+in+st.+louis, accessed on 11/11/2013

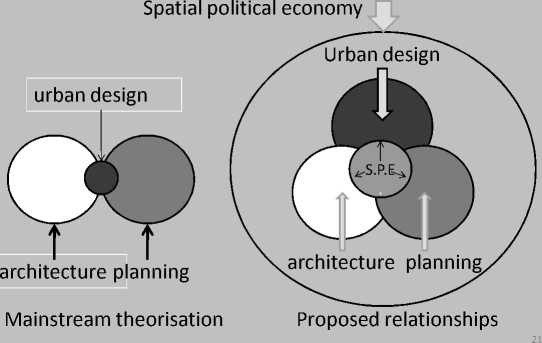

While Sert’s definition secured the discipline for the architectural profession, it also created an intellectual and theoretical vacuum. After all, how can the objects of human labour (buildings and spaces in this instance) - create satisfactory explanations of their own existence without recourse to the forces that created them? Nonetheless, the design dimension of built form was colonised by architecture, and the development control dimension (regulation) was similarly colonised by planning (Figure 4). To counter this, an entirely new relationship is proposed (Figure 5).

But until the 1970’s planning was almost completely dominated by architects, and had been since the inception in Britain of the Town Planning Institute in 1913. Consequently architecture exerted singular influence over urban space as a whole, one originating in the instigation of professional monopolies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Illich 1977, Gouldner 1989, Carter 1985). As long as this situation prevailed, no social theory of architecture could evolve. Aesthetics and technology dominated as themes, and the idea that an appropriate theoretical base for architecture could be found in the organisation of social relations through built form was nowhere to be seen.

conceptions

Figures 4 and 5. Mainstream urban design and the proposed new conceptual system Source: Author

The Architectural Imaginary

So the question is, how is architecture to be understood? This seems like a simple problem, given some ten thousand years of architectural production. Some may be satisfied with architectural theory to date, but to others it is clear that something huge is missing - something that for all practical purposes renders prevailing concepts somewhat inert. Historically, we have inherited two dominant paradigms. First that architecture is a reflection of particular aesthetic choices and traditions (Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Modernism, Postmodernism etc.). Second that it is defined by its own structural logic, by its technology in use (Romanesque, Gothic, Constructivist etc). But in neither of these cases do we really find satisfaction (Hays 2000, Salingaros 2006, Johnson 1994). Using either logic or intuition, explanations seem partial and inherently incomplete. The question remains, ‘what makes architecture’? Or even more to the point, what makes architects?

Architecture has failed in a fundamental way to satisfactorily explain its material and symbolic existence - first because it’s dominant paradigms have made this impossible. Second, in colonising urban design in its own image throughout the twentieth century, it has weakened rather than strengthened its own integrity. In Sert’s terms, mainstream urban design is merely a set of professional practices, supported by an anarchy of ideas that have little substance i.e. they do not cohere in any significant manner that would serve as the foundation for substantial theory (Cuthbert 2007). So-called ‘theory’ in architectural and urban design, as Sert has suggested, emerges from projects, not from the historical and material growth of cities, originating let’s say, with Ҫatal Huyuk around 7000 BC. Assuming we limit urban design to project design, then how do we explain the formal arrangements of the rest of the planet, from squatter settlements to conurbations? Do we also assume in the process that none of this has been designed in some manner, whether by informal human activity, or from the ravings of ministers, princes, monarchs, oligarchs, dictators, tyrants, the state in its various reincarnations, or international monopoly capital? Or indeed that history in its entirety prior to 1953 somehow did not qualify? I summarised this position as follows.

"Where Sert got it wrong was in believing that he could monopolise history, brand it, turn it into a commodity, and in the process capture the cultural capital represented in the product. But in the process of naming, he reduced the vast social complexity of urban form generation to an endless regression of architectural compositions" (Cuthbert 2009: 443).

In contrast to this cultural world view, the new urban design encompasses all urban form, not merely that generated by the architectural profession over the last sixty years. But to do this, we cannot merely extend or revamp the mainstream (Cullen 1961, Bacon 1967, Alexander 1987, Newman 1980, Rowe and Koetter 1979, Lynch 1981, Gosling and Maitland 1984, Hillier and Hanson 1984, Vernez- Moudon 1992, Salingaros 1998 1999, Carmona 1996, Schurch 1999 etc.). Nor can we rely on professional institutions for assistance, since they are heavily compromised due to their absorption by the capitalist system as a whole - dealing with private clients, establishing private firms or becoming architect-developers i.e. companies, thus deleting the original meaning of professionalism. Therefore we cannot rely on any significant explanations (let alone theory) emerging from such an ideologically compromised situation whereby professionals become commodity producers in commodity producing society. The intention of the New Urban Design is to bypass this dilemma in its entirety by simultaneously accommodating architectural theory, mainstream urban design and urban planning, but in the process, reconstructing relationships and re-establishing priorities into a single theorised field (Cuthbert 2003, 2006, 2007, and 2011).

While architecture qua building accommodates humanity in various forms in its entirety, we have no theory of architecture that acknowledges this fact. Nor do we have any generally accepted recognition that it emerges from, and is configured by this same reality. One possible explanation is that in the absence of social theory, the enigma of architecture as a realm of expert and arcane knowledge and its monopoly in professional hands can remain secure, but only by distorting reality in the interests of selfpreservation. The idea that architecture is socially produced, including the imagination of the architects themselves, is a threatening idea and thus remains virtually stillborn in the architectural lexicon. Slogans such as architecture is frozen music (Goethe 1829), less is more (Robert Browning 1855, adopted by Mies Van Der Rohe), form follows function (Louis Sullivan 1896), and a house is a machine for living in (Pierre Jeanneret ca. 1930) - have wielded a massive influence disproportionate to their content, and retain much of their power today within architectural professions worldwide. In none of these is it recognised that architecture and the architectural imaginary are socially produced.

Somewhere in the journey to the present the ideological forms adopted by architecture in respect to modernity and postmodernity excluded any major attempt to present its history,

theories, political ambitions, and its formal arrangements within capitalism as a social phenomenon. The main reason for this overall hiatus is that the production and reproduction of architecture has been abstracted away from the production and reproduction of society. The existence of architecture as a phenomenon has been decided by architects operating as a caucus, delineating what architecture is or is not by various forms of practice, professional interest, a host of awards and the colonisation of public institutions such as tertiary educational programs. Overall, the cult of personality by architects triumphed over any need to further theorise architecture, since logically, the theory was inherent to the practice of architecture and was transmitted by the adage ‘watch my lips move’.

As previously mentioned, any synergy between individuals was wholly absent, genius or otherwise. With the exception of a few emancipated theorists, architecture was neither more nor less than what architects practiced (Korilos 1979; Dickens 1979,1981,Tafuri 1979, Krier 1975 and 1978, Krier and Culot 1979, Knesl 1984, Clarke 1989, King 1996, Knox 1982; Sklair 2005 and 2006, Easterling, 2006). But we can push this idea even further. Insofar as architecture may be represented in as the atoms of environmental structure, it can never of itself suggest its own laws of motion, its materiality and its form (Alexander and Poyner 1967). Such laws can only emanate from the environment within which architecture is encompassed, namely that of society and the production of social space. So at this point we must introduce another key idea, that architecture and urban design are not the same phenomenon at all.

The Importance of Political Economy to the New Urban Design.

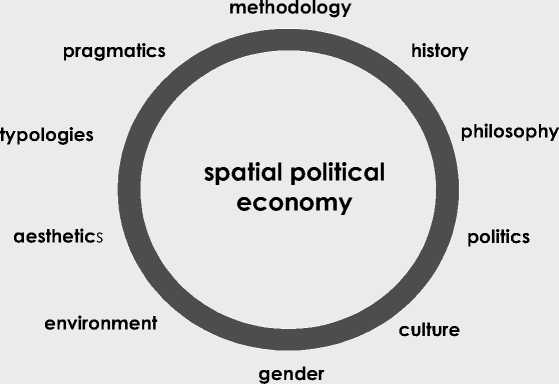

In order to pursue this argument, we must separate out mainstream urban design, from the New Urban Design, since the guiding ideologies of the former were dominated by architects and planners. The New Urban Design is rooted to social theory in the form of political economy (not of Smith but of Marx) in particular its morphing into spatial political economy that is widely understood in the social sciences but has not yet penetrated architecture. Political economy is currently used in the sense of radical economics rather than the bourgeois economics of Adam Smith and Ricardo. This perspective allows us to view the relation between society and space in a radically different manner from that of the mainstream. While architecture and the New Urban Design are indeed related symbiotically, we can argue that they are in fact opposites, but nonetheless complementary in the Chinese sense of Yin and Yang.

To clarify this idea somewhat, it may be argued that architecture is fundamentally about the private realm of property ownership, of social exclusion, security and defence, of closed systems and climate control. Its fundamental unit is the building. There are few if any buildings that cannot be locked up at night, and increasingly so where access during the day requires significant security clearance and surveillance. It is a wholly material phenomenon. In contrast, the New Urban Design is about the public sphere and the public realm, community, freedom of movement, resistance to oppression and democratic social ideals. In essence it is evanescent with public space its fundamental concern. So it can be argued that it has no material existence. Architecture is material and closed, urban design is immaterial and open. The urban is the region where the private realm of architecture meets the public realm of the new urban design. And of course they need each other. This fact is probably best expressed by Manuel Castells definition of urban design:

"We call urban social change the redefinition of urban meaning. We call urban planning the negotiated adaptation of urban functions to a shared urban meaning. We call urban design the attempt to express a shared urban meaning in certain urban forms" (Castells 1983:303-304).

While Castells denotes the importance of urban form to urban design, until that time, the great social scientists (Marx, Durkheim, Simmel, and others) – had not been interested in

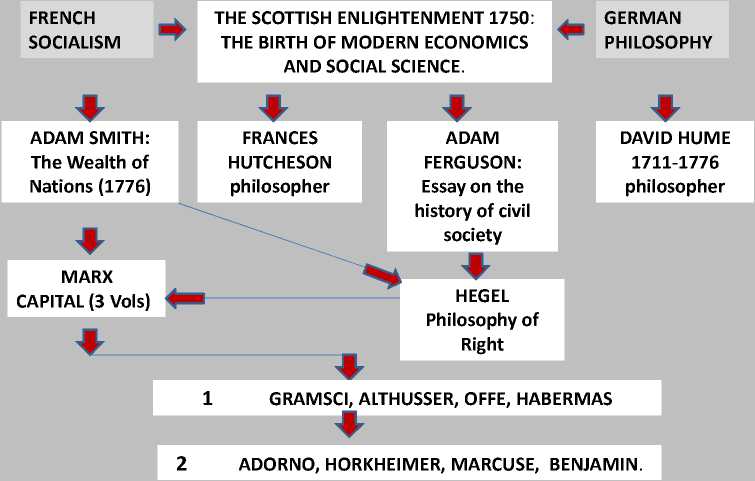

space, concentrating instead on the social forces that produced it (Coser 1977). This process was called the study of Political Economy that had originated in a classic text, namely the Wealth of Nations written by Adam Smith in 1776, one that introduced the concept of economics to modernity. In the nineteenth century, by far the greatest interventions were Marx’ four volumes of Capital, and with Marx’ and Engels’ the Condition of the Working Class in England they fully exposed the ravages of the capitalist system of the time. But it was up to the etchings of Gustave Doré to convey the tangible reality of poverty existing in London in 1872. The progress of Political Economy as a discipline is given in Figure 6. The single exception to this rule was the Chicago School of Urban Ecology which treated urbanism as a natural phenomenon akin to other life forms in nature, and from which it derived much of its vocabulary – colonisation and succession, territory, symbiosis etc (Lewis Wirth). While interesting, it could be described as a method in search of a theory, and because of this, it slowly became extinct as a process of critical engagement with the political economy of social life.

POLITICAL ECONOMY IS THE STUDY OF AGGREGATE ECONOMIC ACTIVITY AND THE POLITICAL ASPECTS OF GOVERNMENT.’

Figure 6. The study of political economy Source: Author

So from approximately 1870 to 1970, space became the province of design, guided by architect planners and their intervention into the state as part of the knowledge class, from which social concepts were ritually excluded (Dunleavy 1981). Space was seen to issue from the architectural profession and the architectural imaginary by a process similar to the Eureka Principle of Archimedes sitting in his bath, or more accurately, off the drawing board. The mainstream urban design of this era was configured to a significant degree by structural functionalism, processes that also resulted in structural social science and fascism in Germany, Italy and Spain from 1930 to 1945. But in the seventies, a revolution occurred in social science that not only extended its mandate into the analysis of the relationships between society and space (its political economy) but importantly, to the forms that it adopted, as well as to the political ideologies that shaped it and the symbolic structures it represented. The central question was whether an urban sociology

was possible. For the first time, such knowledge opened up the possibility of a unified field for architecture, urban design and urban planning, with little direct reference to either (Lefebvre 1970, Castells 1976, 1977, 1983, Scott and Roweis 1977, Harvey 1973).

At the centre of the revolution were two key figures, Henri Lefebvre and Manuel Castells, but nonetheless reinforced by many other social theorists such as Alain Touraine, Alain Lipietz, Claus Offe, David Harvey, and Mark Gottdiener. However it was predominantly Castells that brought to consciousness the possibility of a spatial political economy whose central effort was to complete the project of Marx and others, by linking social structures with spatial structures, which then offered the possibility to include architecture and urban design as significant dimensions of this theory. A key point brought to this overall trajectory was the idea that to be scientific, a discipline should have either a theoretical object, a real object, or preferably both (see Figure7).

|

Architecture |

Mainstream urban design |

Urban planning |

The new urban design | |

|

Theoretical object |

? |

? |

? |

Civil society |

|

Real object |

The building |

The project |

? |

The public realm |

Figure 7. Theoretical and real objects of study in the environmental disciplines Source: Author

Despite the fact that this might seem rather obvious, such an analysis has not yet appeared in the literature. In addition, a rather interesting point surfaces - that only the new urban design has both a real and a theoretical object, although this idea has already met with considerable resistance in the debates I have already encountered.

Nonetheless, it remains undeniable that the real object of architecture is the individual building, whether or not individual buildings are multiplied or otherwise in grand projects worldwide. At the same time, its theoretical object is unclear, debateable, and undefined. On the other hand urban planning as I have indicated above has neither a real nor a theoretical object since its actions are determined by the state. The idea that it has ‘community interests at heart’ or that it focuses on the ‘general good’ are ideological with little foundation in reality. Mainstream urban design is somewhat in the same state as urban planning, but at least it has the project as its real object. But when we come to the New Urban Design, its objects are unambiguous, its real object is the public realm and its theoretical object is civil society. If this argument is accepted, then it would appear that the New Urban Design differs from the other three practices in that it has greater integrity as a theoretical and practical endeavour, as well as having the capacity to generate a unified field at the centre of environmental design knowledge.

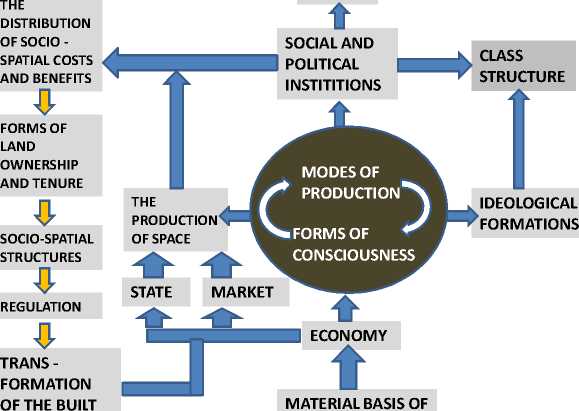

The implications however are transparent. To set an appropriate foundation for the New Urban Design, we must resort to theory that is up to the task. Given that civil society is the theoretical object, no architectural or planning ‘theory’ exists that can encompass this phenomenon. In addition, we need a theory that can synthesise society and space, without the ideological distortions of neo-classical economics and its catechism ‘a dollar is a dollar to whomever the dollar accrues,’ thus perpetuating the false consciousness of capitalism and market economics. The only discipline we have to do this is political economy, particularly spatial political economy which in practice breaks down into three components, urban geography, urban economics and urban sociology. In addition, the general schema of this position is suggested in Figure 8, one that clearly indicates the significance of the overall production of space for the new urban design. Furthermore, just two quotations are sufficient to indicate first, the nature of the system, and second, a reflection on its internal dynamics governing its form:

"In other words, the social and property relations of capitalism create an urban process which repels that on which its continued existence ultimately depends, i.e. collective action in the form of planning. Beneath the appearance of social control over the evolution of the urban system lies the inexorable dynamic of a complex of land-contingent events that is essentially out of control" (Dear and Scott 1980:1100).

“The emergence of a distinct spatial structure with the rise of capitalism is not a contradiction free process. In order to overcome spatial barriers and to annihilate space with time, spatial structures are created that themselves act as barriers to further accumulation. The geographical landscape which fixed and immobile capital comprises is both a crowning glory of past capitalist development and a prison which inhibits the further progress of accumulation, because the very building of this landscape is antithetical to the “tearing down of spatial barriers” and ultimately to the annihilation of space with time” (David Harvey 1975:13).

Reprise

The above quotations clearly indicate the direct relation between economic systems, their ideological assumptions, the spatial matrix that is produced, and the actuality of urban forms so created. Furthermore, we can see that the economic systems that have been developing over historical time – modes of production (amplified below) – are also forms of consciousness that profoundly affect everyone though not necessarily for the better. From this we may also deduce that even the creative process, one based upon the idea of original thought, is socially produced and transmitted. While it would be pushing things too far to say that there is no such thing as originality, all discoveries have a massive historical component, to the point that there is a certain inevitably in human progress due to the demands made within the productive process – new invention is already preprogrammed into the system, and the future has already been made part of the past.

So we can see that the overall process of form creation is not arbitrary. In the West it has been built upon the evolution of the capitalist system. This system is not only contradictory- paradoxically its conflicts and inconsistencies must be maintained for the system to survive (class struggle, wars between the various capitals, struggles between capital and the state etc.). I have already mentioned that the great social scientists of the past had no interest in space, and that Manuel Castells moved debates into the dimension of social relations and spatial structures.

What I will now elaborate is that the new urban design, in accepting these foundations, takes this process to its logical conclusion by suggesting that even spatial forms are not arbitrary, but surface from exactly these same processes (see Figure 8). This becomes rather obvious when we examine in greater detail the concept of a mode of production, a fundamental part of Marx’ concept of history, but not without its flaws. I will develop this concept below in relation to the New Urban Design.

THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE

CIVIL

SOCIETY

LIFE AND HISTORY

ENVIRONMENT

LAW

EDUCATION

RELIGION

-

Figure 8. The political economy of space Source: Author

Modes of Production: Forms of Space

While I am primarily concerned here with the capitalist system (as opposed to precapitalist, socialist or communist states), all forms of society contain contradictions, repressions, belief systems, forms of law and other evolving social processes. Such processes are wrapped in what Marx referred to as a mode of production, a concept that is essential to any Marxian concept of history. Such climacteric shifts were also seen to evolve in stages which corresponded to the creation of increasingly greater storage of the surplus product (wealth generated by labour but expropriated by capital). This idea has several dimensions. First, historical materialism suggests that any substantial theory of history must come from the dynamics involved in the creation of social life as a whole, fundamentally the structuring of its political economy and its ideological assumptions. Second that modes of production are progressive and change on the basis of revolution, a necessary process that allows one mode to be replaced by another (revolution occurring when the forces of production have outstripped the relations of production). Third, that congruent modes of production may occur within the social formation, but are subsumed to the dominant mode. Marx also distinguished three pre- capitalist modes, The Asiatic mode of production, ancient slavery, and feudalism. Alternative ways of looking at this problematic also exist, for example:

"The sequence [of history] has three main stages: production for use, production for exchange, and production for surplus- value. The passage from the first to the second stage is mediated by external trade, that between the second and the third by internal trade. Hence we may also consider the process consisting of five successive stages" (Elster 1985:310).

This is the case for example within certain existing capitalist societies, where tribal and feudal social relations may remain in certain parts of the economy, or indeed within socialist states such as China. Despite the fact that Marx’ theory of history is the only one we have – all else being driven by method since the Annalles School of Paris was

founded in1928 -. We can argue that there can be no theory of history since it all depends on whose interpretation we accept:

"For these reasons, the past we study as historians is not the past “as it really was”. Rather it is what it felt like to be in it. The growing bibliography of the history of passions, sentiments, anxieties and the like is a measurable recognition of this" (Armesto 2002:155).

Nonetheless, as Marx said in his preface to Capital,

"The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. At a certain stage of their development the material forces of production in society come into conflict with the existing relations of production, or – what is but a legal expression of the same thing – with the property relations within which they had been at work before."

While Marx separated out the material conditions of production – the base, from its ideological superstructure which according to Marxist orthodoxy it determined, such a mechanistic relation is indeed hard to sustain. For example in Reading Capital Althusser and Balibar rejected a deterministic interpretations of the base - superstructure relationship, suggesting instead that the economic, political and ideological functions should be perceived as levels forming a structured whole. They believed that in given cases, the ideological structure determined certain aspects of the base economy - so the dynamics of a mode of production or indeed its collapse is not as simple as it might appear. Differently stated, it is not always apparent that superstructural formations (ideologies) can have a serious influence on what happens in society, and religion, culture, concepts of law, education and philosophy cannot so easily be reduced to noneconomic institutions. For example, quite recently the idea of the culture industry which originated with Theodore Adorno in 1944, achieved concrete status with the work of Allen Scott in The Cultural Economy of Cities (Scott 2000), a text which firmly impacted the idea that a non-economic institution (culture) had become a major site of economic production.

So clearly there are several problems associated with the idea of modes of production. For example, China and Russia are both examples of a contradiction. Both countries ‘jumped’ directly from feudalism into communism and have now adopted the market system of capitalism. They denied the implicit teleology of a historical progression. So these revolutions on the one hand deny Marx’ general progress of history since China and Russia were first supposed to enter capitalism from feudalism. On the other hand we can argue that Marx theory is correct. Both jumped, but they jumped too far and too soon, and now must regress to Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand of the market’ before sufficient surplus is generated to allow true communism to flourish. Another problematic is whether the concept of a mode of production can really only be applied to the various stages of capitalist development.

Godelier suggests that prior forms of social life should really be referred to as modes of subsistence. The reason for this distinction is due to the fact that the relations of production do not exist in a separate and distinct state, since for example, ‘in certain forms of society kinship relations can function from the inside as social relations of production, whilst in others, conversely, politics plays this role and in yet others it can be played by religion’ Godelier (1986:68). Within more developed societies, production has been institutionalised, and its internal dynamics are organised round production processes paid for by wage labour. Nonetheless, the idea of modes of production is adequate to demonstrate the point that forms of building and space emerge from the material and productive forces and that these same forces generate demands for urban forms and spaces that are useful to fulfil the demands of the social relations they contain (Figure 9).

Political economy of development

|

SOCIAL RELATIONS |

ECONOMIC RELATIONS | ||

|

1 |

hunter gatherers |

familial |

patriarchy |

|

2 |

tribal communities |

clan |

group consensus |

|

3 |

slave states |

race divided |

nepotism |

|

4 |

feudalism |

class relations x 2 |

city states |

|

5 |

merchant capitalism |

capitalist class relations x 3. introduction of middle class |

militarism colonisation |

|

6 |

industrial capital |

class relations + org labour ‘modernity’ |

militarism imperialism |

|

7 |

commercial capitalism |

class relations + disorganised global labour |

state corporatism |

|

8 |

globalisation/ informational cap. |

Class relations + global real/ virtual relations. |

state neo-corporatism public- private sector. |

Modes of Production

-

Figure 9. Modes of production

Source: Author

While it is not possible in the space available to me to go into the detail of each mode of production and the places and spaces it generates (or demands), it is possible to trace the urban design consequences of each mode of production in great detail. Nonetheless I have tried to suggest below some of these relationships that is between the political economy of space and its formal consequences in the built environment. This list is by no means all inclusive, and it can only give an indication of the significance of the current global economy to the spaces it generates (see Figure 10).

By now it should be clear that the production of urban form – the New Urban Design, must surface from deep within the social formation and its forms of consciousness. The political economy of space that evolves generates a highly sophisticated process whereby land uses, buildings and spaces surface from the internal dynamics in the development of the capitalist mode of production. In other words explanations of urban design must in the first instance, emerge from the processes that create the material conditions of life, and not from aesthetic, technical or other ‘theory’ in architecture or planning, and the associated mainstream urban design. The instances of this are legion, but perhaps three will suffice.

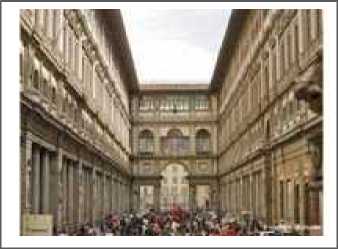

First, in Europe during the sixteenth century a new form of social order called Merchant Capitalism became fully developed in great cities of Europe, for example in Florence, Venice, Amsterdam, and London. One of the most fundamental aspects of this early form of capitalism was that it was the first period in history where trade was dependent on contracts between parties. On this basis a massive bureaucracy developed, and a new building type was demanded that had never existed in prior epochs in quite the same way, one that carpeted the centres of major cities throughout Europe. The name of the building was the office, and one of the most famous art galleries of all time, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence actually means ‘office’ in translation (Figure 11). The ‘office’ gallery reflected its origins as a new building typology enclosing the administrative apparatus of the state. The Uffizi began as part of the massive building of offices in Italy in 1650, to ensure Italy’s capacity to compete within the evolving economies in Western Europe, and the urban design of the period was a direct consequence of pre-existing economic

imperatives. Reflecting on the conundrum as to whether the chicken or the egg came first, in this context, it was indeed the office that invented the architect, not the architect that invented the office.

themaγerjal Andsymbouc production of forms and spaces.

|

ECONOMIC PROCESS |

SPATIAL AND FORMAL PROCESS | |

|

1 |

Branding |

Themed environments |

|

2 |

Spectacular consumption |

Colliseums of various types |

|

3 |

Economies of scale |

Hypermarkets, malls |

|

4 |

Commodification of history |

Conservation districts |

|

5 |

Accommodation of the New Class |

Cultural∕Cappuccino environments |

|

6 |

Areas themed bγ age. association or interest. |

Cohort consumption areas |

|

7 |

The cultural economy ∕ luxury consumption |

Specialist tourist enclaves |

|

8 |

Neo Corporate architecture as GDP |

Blue chip buildings and environments. |

|

9 |

Shifting class. ethnic and racial fractions |

Gated Communities. |

|

10 |

Reserve army of labour |

Increasing alienation of public housing |

|

11 |

Purchase of Symbolic capital |

New Urbanist enclaves. |

|

12 |

Commodified entertainment |

Dysneyfication. cultural Chernobyls |

|

13 |

Tourism (entertainment) |

Spaces of simulacra |

|

14 |

Tourism (transport) |

Themeports (airports as destination |

Figure 10. Relationships between the contemporary political economy and spatial structures Source: Author

Second, Paris has long been offered as a classic example of urban beautification, the ultimate aesthetic exercise which resulted in one of the world’s most beautiful cities (Figure 11). But in fact the causes were neither an aesthetic nor a psychological caprice as it might seem with reference to the mainstream urban design literature. Around 1850, a massive program of rebuilding was undertaken by Napoleon the Third, and a civil servant by the name of Georges-Eugène Haussman. The social logic behind this activity was first, to improve the circulation of commodities, and second, as an instrument of social control. In the first case, Paris was in competition with other great cities in Europe for primacy in trade. The problem that it had was its medieval structure of streets and alleys that had no discernible organisation. In terms of industrial production, Paris was a transport planner’s nightmare. Inefficiencies in the supply of materials, the manufacture of commodities and the distribution and export of finished products represented a massive cost to the overall success of capitalist production. To correct this, Haussmann replanned the centre of Paris by systematically destroying the medieval city and 60% of its buildings.

In order to accelerate development, new railway stations, sewerage and other infrastructure built at the same time made a massive contribution to increased efficiency in the economy. But most of all, in replanning the city the extensive network of broad boulevards that emerged had a second, darker purpose in mind. In addition to the more rapid circulation of commodities, the efficient deployment of troops was also paramount. The rebuilding of Paris around 1850 occurred between two massive revolutions, the first in 1848 and the second in 1871 after the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian war and the uprising of the working class. It was this reconstruction that allowed the Communards to be easily crushed by government forces during the second revolution. In addition,

many ‘aesthetic’ values were formulaic, such as maintaining a four story limit to all buildings, the use of apartments as a basic housing form, and the standardisation of architectural details in construction.

Figure 12. Paris Boulevards

Source: https://www.wallpapersdepot.net accessed on 11/11/2013

Figure 11.Uffizzi Gallery Florence Source: https://www.florencedailynews. com, accessed on 11/11/2013

Figure 13. Vienna ca.1900

Source: https://www.Blogs.getty.edu, accessed 11/11/2013

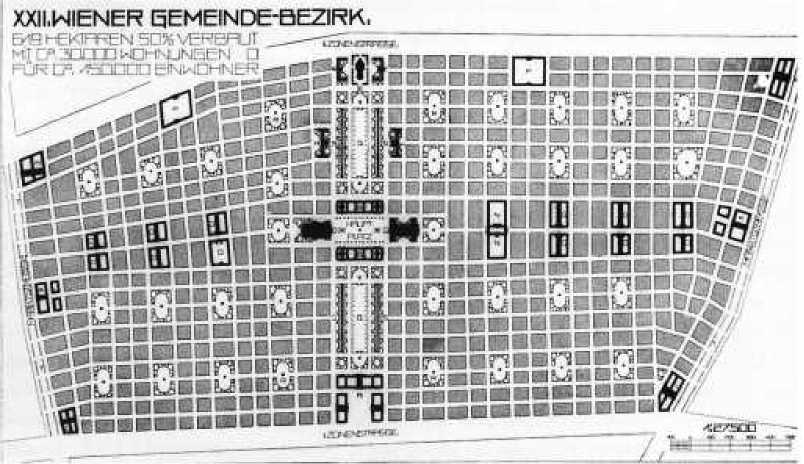

Thirdly, in Vienna at the fin de siècle (turn of the century), a massive climacteric in urban design took place, famously expressed in true architectural fashion as a battle between the design principles of two individuals, Camillo Sitte and Otto Wagner (Sitte 1889, Collins and Collins 1989, Schorske 1981). While their ideas were no doubt important, neither were they virgin births, and the real conflict was not one of personalities, but between medieval forms of thought and those of modernity. What Wagner and Sitte did was to present some of the dimensions of social change that were pre-existing in Viennese society at the end of the nineteenth century. Arguably the debate between Sitte and Wagner over urban design principles would have taken place whether or not they existed, since society already contained many explosive ideas about social change and development that were independent to their expression by the personalities of the time. While mainstream urban design has always expressed the individualistic nature of social change, the New Urban Design looks at the political economy of the time for its answers.

The answers that ensue involve the vortex of ideas that enveloped Vienna at the turn of the nineteenth century, where developments in psychoanalysis, music, literature, art and architecture had few parallels, what Schorske refers to as ‘a commonly accepted architecture of the historical process in the culture as a whole’ (Schorske 1981:xxi). He points out that the knowledge practiced by these humanists was a necessary part in the formulation of twentieth century culture – one that informed the urban design of the time. The cohesiveness of bourgeois culture integrated intellectual life as it did in no other contemporary city. While Otto Wagner’s planning prevailed, heralding a new functionalism focussed on circulation and public health, the seeds of this philosophy were already transparent in the Ringstrasse development of 1860. In other words, Wagner’s functionalism already existed in historical precedent. Wagner was a vehicle for ideas and strategies already in existence, one which he felt compelled to take to a rather logical conclusion in his Modular City District of 1911 (Figure 14) which held clear economic advantages over those of the medieval city.

Figure 14. Modular City District 22 of Vienna (1911)

Source: (Schorske 1981:5)

The Components of a Unified Field for Urban Design.

The above examples support the idea that urban design requires a new understanding that contains several key components:

-

• It should have as its real object the public realm and its theoretical object in civil society.

-

• Its intellectual origins are therefore in social theory, not aesthetics or technics.

-

• The only discipline capable of developing such an understanding is political economy.

-

• The relationship between architecture, urban design and urban planning needs to be revisited.

-

• The New Urban Design must be placed at the centre of debates, not at the margins.

The question I had to answer was how to approach this problem. My first assumption was that the new urban design could not evolve from the old, for reasons mentioned above. Prime among these was that while urban design was considered an important part of architecture and planning, it was viewed as a mere adjunct to the centrality of both

disciplines. The second was a paradox. While the old urban design could not reconstruct the new, it could not be abandoned either. The logical response was that the new urban design had to be theorised at a scale where the old could be incorporated. The third outcome was that theorising the new urban design would necessarily be done best by abandoning all professional distinctions as to its nature. As Bernard Shaw once remarked ‘all professions are conspiracies against the public’ and this observation is as valid today as it was in the past. Each of these considerations could be resolved by using spatial political economy as a base, rather than the anarchy of planning and architectural theory that has existed for over a century. But in adopting this approach I also accepted the fact that there were also problems with the word theory. The term had been used so loosely within the disciplines of architecture and urban planning that they had little practical use or function. So the idea of developing a new theory seemed self-defeating. Instead I chose to use the term unified field. This is particularly germane when using spatial political economy, which constitutes an amalgam of different approaches yet using similar conceptual tools. Rather than resorting to the concept of a single theory that has to stand until it fails, a concept useful for example in physics, what the New Urban Design needed was a flexible system that could evolve. It also needed to cohere within an overall set of principles originating within Marxist theory of the mid nineteenth century, but more fully developed within spatial political economy since 1975. So the New Urban Design deliberately does not constitute a new theory, and instead adopts the concept of a unified field as a more flexible and evolutionary system.

URBAN DESIGN TRILOGY: COMMON FRAMEWORK

Figure 15. The components of the New Urban Design

Source: Author

The next question was how the elements of this unified field were to be defined. The first principle already stated was that the glue that kept everything together was spatial political economy, which unified all the dimensions of the problem. For example if aesthetics were to be discussed, it should be from this perspective – key texts for example in this area being those of Vasquez (1973), Zis (1977), Marcuse (1968), Raphael (1981), Eagleton 1990, and Graham (1997). The same logic would have to apply to all other elements however many there might be. In addition, the choice of elements would have to

follow the elementary law of systems- while there would be a necessary overlap, there should be no redundancy (Simon 1969). Finally, what was also important were the rules governing language - that all words (distinctions) are arbitrary and only make sense in their relation to each other and the social meaning allocated to them. The same logic should apply to each chosen element. Their overall meaning within the system is to a large extent arbitrary unless subject to socially necessary rules of engagement.

The dimensions I chose are given in Figure 15 (above). Not obvious from the figure is that these are deliberately grouped into regions that have more powerful or direct connections, namely Theory (in volume 2), or Method, (in volume 3), History and Philosophy. Next, we have Politics, Culture and Gender. Third, Environment, Aesthetics and Typologies. Pragmatics is a necessary category that deals with action rather than analysis. Each of these dimensions is covered in a single chapter in each of three books – in other words the chapter structure does not vary. This permits a matrix reading of the material, either in series or in parallel. For example, Aesthetics can be read across all three books from base material to theory and then to method. Alternatively, all dimensions may be read from e.g. in terms of origins, theory, or method, each perspective in a single volume.

Conclusion

In proposing a new field of human activity, or rather the redirection of history to new purposes, much of the subtlety of debate suffers from compression. Needless to say this is probably true of this article which needs the support of prior work for a true reading. To this extent some argument has been overstated, some insufficiently explained. Despite my remarks, I do accept that genius cannot be discounted, that creativity should be encouraged in every pursuit, and that architecture is a magnificent art. So I would welcome the next advance on my work, and indeed encourage it. All of the necessary trawling through the intellectual developments of centuries has one purpose, to help us understand the wonder of human activity that results in world cities, great architecture, magnificent feats of planning and urban development, and the inventions that make this possible. But there is also a dark side. We must not forget the squalor, degradation, poverty and despair that haunt millions of the world’s inhabitants, and that urban design applies to the built environment as a whole, not merely to projects after 1950 (Easterling 2006, Davis 2010).

If our effort is to understand the built environment and its multitude of forms, we must develop the tools to understand this environment in its entirety, unsullied by professional self- interest or academic specialism. To this extent, The New Urban Design must replace the old, incorporating its best features, yet rejecting the myopic nature of its activities to date. Above I have tried to suggest how we move forward, and a simple comparison between the two logics, mainstream urban design and the New Urban Design would hopefully support my argument for a new beginning. This clearly has implications for the teaching of urban design within tertiary educational institutions, a revolution in fact as to how the subject is taught and practiced. While no system is perfect, I paraphrase Le Corbusier’s comment about his modular system of proportion – ‘Will the New Urban design necessarily result in better urban design? No - but it will make bad urban design much more difficult.’

Bibliography

Adorno, T (Ed.) (1991) The Culture Industry London: Routledge.

Alexander, C (1977) A Pattern Language New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, C (1987) A New Theory of Urban Design New York: Oxford University Press.

Althusser, L and Balibar, E (1970) Reading Capital London: New Left Books.

Bacon, E (1967) The Design of Cities New York NY: The Viking Press.

Broadbent, G (1990) Emerging concepts in Urban Space Design New York: Van Nostrand.

Carmona, M (1996) 'Controlling urban design Part 1: A possible renaissance' The Journal of Urban Design 1(1), p: 47-73.

Carter, B (1985) Capitalism, Class Conflict and the New Middle Class London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

Castells, M (1977) The Urban Question- a Marxist Approach London: Edwin Arnold.

Castells, M (1983) The City and the Grassroots, a Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Castells, M in in Pickvance, C (Ed.) (1976) 'Is there an urban sociology?' Urban Sociology-Critical Essays. London: Tavistock, p: Chapter 1, 27-42.

Collins, G R and Collins C C (1989) Camillo Sitte: The Birth of Modern City Planning.

Mineola, New York: Dover Publications.

Coser, L A (1977) Masters of Sociological Thought New York N.Y: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovitch.

Cullen, G (1961) Townscape. London: The Architectural Press.

Cuthbert, A R (1985) 'Architecture, society and space: the high-density question reexamined. Progress in Planning 24 (2), London: Pergamon, p: 73-160.

Cuthbert, A R (2003) (ed.) Designing Cities Oxford: Blackwell.

Cuthbert, A R (2006) The Form of Cities Oxford: Blackwell.

Cuthbert, A R (2007) 'Urban design: requiem for an era - review and critique of the last

50 years' Special Issue. Urban Design International 12(4), p: 177-226.

Cuthbert, A R (2009) Review Article. Krieger. The Journal of Urban Design.

Cuthbert, A R (2011) Understanding Cities Oxford: Routledge.

Diani, M and Ingraham, C (Eds) (1989) The Economic Currency of Architectural Aesthetics Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Dickens, P (1979) 'Marxism and architectural theory - a critique of recent work,' Environment and Planning B (6), p: 105-116.

Dickens, P. (1981) The hut and the machine-towards a social theory of architecture.

Architectural Design, 51(1), p: 32-45.

Eagleton, T (1990) The Ideology of the Aesthetic Oxford: Blackwell.

Easterling, K (2006) Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and its Political Masquerades Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

Fernandez -Armesto, F (2002) The World, a History. Vol. 1. Illinois: University of Notre Dame.

Godelier, M (1988) The Mental and the Material London: Verso.

Gosling, D and Maitland, B (1984) Concepts of Urban Design London: Academy.

Gouldner, A (1989) The Future of Intellectuals and the Rise of the New Class New York: Seabury Press.

Graham, G (1997) Philosophy of the Arts: An introduction to Aesthetics London: Routledge.

Harvey, D (1973) Social Justice and the City London: Arnold.

Hays, K M (Ed.) (2000) Architectural Theory Since 1968 Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Hillier, W and Hanson, J (1984) The Social Logic of Space Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Illich, I (1977) Disabling Professions London: Marion Boyars.

Johnson, P A (1994) The Theory of Architecture: Concepts, Themes and Practices New York: Van Nostrand Reinholdt.

King, R (1996) Emancipating Space - Geography, Architecture and Urban Design New York: Guilford Press.

Knesl, J A (1984) 'The powers of architecture' Environment and Planning D. Society and Space, (1), p: 3-22.

Knox, P (1982) 'The social production of the built environment' Ekistics 295. July-August 1982.

Korilos, T S (1979) 'Sociology of architecture – an emerging perspective' Ekistics 12 (15), p: 24-34.

Krieger, A and Saunders, S (Eds.) (2009) Urban Design Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Krier, L (1975) The Reconstruction of the City Brussels: Archives D’architecture Moderne.

Krier, L (1978) 'Urban Transformations' Special Issue. The Architectural Design.

Krier, L and Culot, L (1979) Counter projects Venice: Archives D’Architecture Moderne.

Lefebvre, H (1970) La Révolution Urbaine Paris: Gallimard.

Lynch, K (1981) A Theory of Good City Form Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Marcuse, H (1978) The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics Boston: Beacon Press.

Marx, K (1954) (original 1887) Capital Volumes 1-4. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Marx, K and Engels, F (1984) (original 1892) The Condition of the Working Class in England London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Newman, O (1973) Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City London: Architectural Press.

Newman, O (1980) Community of Interest Garden City: Anchor Press.

Raphael, M (1981) Proudhon, Marx, Picasso- Three Essays in Marxist Aesthetics London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Rowe, C & Koetter, F (1978) Collage City Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Salingaros, N (1998) 'Theory of the Urban Web' The Journal of Urban Design 3(1), p: 53-72.

Salingaros, N (1999) 'Urban space and its information field' The Journal of Urban Design 4(1), p: 29-50.

Salingaros, N (2006) A Theory of Architecture Solingen: Umbau Verlag.

Schorske, C A (1981) Fin de Siècle- Politics and Culture New York: Vintage.

Schurch, T W (1999) 'Reconsidering urban design: thoughts about its definition and status as a field or profession' Journal of Urban Design, 4(1), p: 5-28.

Scott, A J (2000) The Cultural Economy of Cities London: Sage

Scott, A J and Roweiss, S T (1977) – 'Urban planning in theory and practice - a reappraisal' Environment and Planning A, Society and Space (9), p: 1097-1119.

Simon, H (1969) The Sciences of the Artificial Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Sitte, C (1945) (Original 1889) The Art of Building Cities: City Building according to Its Artistic Fundamentals New York: Reinhold.

Sklair, L (2005) ' The transnationalist capitalist class and contemporary architecture in globalising cities' The International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29(3), p: 485-500.

Sklair, L (2006) 'Ikonic Architecture and Capitalist Globalisation' City 10 (1), p: 21-47.

Tafuri, M (1979) Architecture and Utopia - Design and Capitalist Development Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Tafuri, M (1987) The Sphere and the Labyrinth Cambridge MA: M.I.T. Press.

Vazquez, A S (1973) Essays in Marxist Aesthetics London: Monthly Review Press.

Vernez-Moudon, A (1992) 'A catholic approach to organizing what urban designers should know' Journal of Urban Design 6 (4), p: 331-49.

Wirth, L (1938) 'Urbanism as a way of life' The American Journal of Sociology 44, (1), p: 1-24.

Zis, A (1977) Foundations of Marxist Aesthetics Moscow: Progress.

Websites accessed

https://www.google.com/search?q=pruittigoe+housing+project+in+st.+louis, Accessed 11/11/2013.

https://www.florencedailynews.com, Accessed 11/11/2013.

https://www.wallpapersdepot.net, Accessed 11/11/2013.

https://www.Blogs.getty.edu, Accessed 11/11/2013.

NOTE – All figures by the author unless stated otherwise.

26 SPACE - VOLUME 1, NO. 1, APRIL 2014

Discussion and feedback