Continuity of Housing Expression based on the Elderly Bugis Culture

on

CONTINUITY OF HOUSING EXPRESSION

RUANG

BASED ON THE ELDERLY BUGIS CULTURE

Kesinambungan Ekspresi Hunian

Berdasarkan Budaya Lansia Orang Bugis

Oleh: Putri Nur Sakinah1, Arina Hayati2*, Muhammad Faqih3

Abstract

Elderly people tend to continue passing down cultural values to the next generation. The Bugis community from South Sulawesi has solid cultural values that relate to rules of life and living called "Siri' na Pesse”. Over time, users' needs and desires for homes change and increase, and subsequently affect the ways the Bugis community perceives its living environments. This research aims to identify aspects and elements that are changed during implementing of the "Siri' na Pesse" conception. This identification is based on the perspective of the elderly group of the Bugis community who live in vernacular houses in Tolitoli, Central Sulawesi. For data collection, this research first distributed questionnaires to get information on concepts applied to the vernacular houses of its participants. However, this method did not provide responses relevant to the research criteria and objective. To seek more detailed information, it was then decided to proceed with participants’ observations and in-depth interviews to find out the extent and reasons for applying “Siri' na Pesse” conception in houses. Study results show that "Siri' na Pesse" conception is applied in some design aspects only, which are mainly in building elements of a vernacular living design. Some conceptions are no longer applied due to participants’ declining understanding of cultural values and conditions surrounding the settlements.

Keywords: Buginese; elderly; housing; siri’ na pesse; values

Abstrak

Lansia cenderung akan mewariskan nilai budaya kepada generasi berikutnya. Suku Bugis memiliki nilai budaya yang kuat terkait dengan aturan hidup dan berhuni yang disebut "Siri' na Pesse". Seiring waktu, kebutuhan penghuni semakin bertambah dan berubah, sehingga terjadi perubahan cara pandang masyarakat terhadap lingkungan huniannya. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengungkap aspek dan elemen yang berubah dalam penerapan nilai “Siri’ na Pesse” pada hunian dari perspektif lansia Bugis. Partisipan penelitian adalah masyarakat lansia yang tinggal di hunian vernakular Bugis di Tolitoli, Sulawesi Tengah. Tahap pertama, riset ini menyebarkan kuesioner untuk mendapatkan informasi nilai-nilai yang diterapkan pada bangunan hunian vernakular oleh partisipan. Hasil kuesioner kurang menunjukkan hasil yang sesuai dengan kriteria dan tujuan penelitian sehingga dibutuhkan metode penelitian lanjutan untuk lebih mendetailkan. Kemudian, observasi partisipan dan wawancara mendalam dilakukan untuk mengetahui sejauh mana dan alasan penerapan nilai ”Siri’ na Pesse” pada hunian. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan nilai “Siri’ na Pesse” hanya diterapkan pada sebagian aspek terutama pada elemen bangunan dalam desain hunian vernakular. Beberapa nilai tidak lagi diterapkan karena menurunnya pemahaman terhadap nilai budaya dan kondisi lingkungan permukiman.

Kata kunci: Bugis; lansia; nilai budaya; hunian; siri’ na pesse

Introduction

James William (1890) investigates individual diversity of cognition based on age and cultural background. With increasing age, adults show decreased performance in cognitive aspects, including processing speed, working memory, long-term memory, and reasoning (Park, 2002). Several studies also show considerable cross-cultural differences in cognition (Nisbett et al., 2001). For example, Asians (e.g., Koreans, Japanese, and Chinese) tend to be holistic – broadly paying attention to the entire context and basing their reasoning on experiential knowledge in culture-based groups (Na et al., 2017)

Culture in a group forms social norms and values that directly influence a person's life process until they age and take on the role of an older person. According to Chonody & Theatre (2018), culture is not static; the process continues to shift and change along with the development of society and the environment. Besides, older people continue to transfer their understanding of their beliefs and values to their descendants (Farage et al., 2012). A form of cultural transfer has existed since ancient times and is still known and sustained by community groups.

One of the tribes in Indonesia that has solid cultural value towards the process of living and building a house is the Bugis tribe from South Sulawesi. The Bugis community strongly believes in cultural values, especially the "Siri' na Pesse" values, which are the main values used as guidelines in designing a house (Naing & Hadi, 2020). However, implementing these values in housing attributes has changed due to a different understanding of the meaning of cultural values and unsupportive environmental conditions. Every community tries to pass down cultural values to their descendants to maintain tradition (Naing & Hadi, 2020). It is also essential to adjust to the current environmental and community conditions if the cultural values are no longer relevant to be applied. Among the Bugis tribe, several aspects of the value of "Siri' na Pesse" are crucial and binding, so they are still applied to housing design. Therefore, the question arises of what aspects of "Siri' na Pesse" are still maintained and which have faded by the Bugis community, especially older people who live in Bugis houses. This research observes "Siri' na Pesse" and Bugis elderly characteristics in vernacular housing design. The aspect of "Siri' na Pesse" is rules, norms, and values (Naing & Iskandar, 2015). Then, the aspect of older people is related to their daily needs and behaviour.

Literature Review

a. Elderly Perception of Value

Older people's social roles and functions in cultural groups have diverse views and values. In general, older adults are considered to have various experiences and specific skills, so their behaviour in the community and with their families is wiser and more prudent (Meutia Farida Hatta, 1989). The experience and expertise of older people become a system of knowledge and guidelines for the next generation's behaviour integrated with cultural rules, norms, and values (Koentjaraningrat, 2011). The diagram of the model of the evaluation process, with minor modifications, explains that ideals, norms, and meaning are a reference used in specific sub-groups to create their environment (Rapoport, 2005, p.52). Ideals are formed by understanding and implementing fundamental values that form certain

perceptions and behaviours (Van Quaquebeke et al., 2014). Meanwhile, norms are informal rules, often unwritten, that determine acceptable actions or are appropriate to particular groups, serving as guidelines for human behaviour (UNICEF, 2021, p. 1). Perceptions that arise in the context of older people also generate motivations/needs, which can then be described through the meaning of understood cultural values.

The relationship between humans and the environment to form spatial behaviour is explained by Lang (1987) through the environmental perception and behaviour approach. Information about the environment is obtained through a perception process guided by schemata, namely memory and cultural values that have been applied for generations. The forms a relationship between perception, cognition, emotional response (affect), and action (spatial behaviour), which affects schemata as a result of behaviour (Lang, 1987, p. 84-85).

One of the tribes that have a particular value towards the way of life and living is the Bugis tribe from South Sulawesi. The shape and structure of the house reflect how the Buginese view the spatial structure of the universe (macrocosm) and human life. There is a strong sense of compliance by the Bugis community in maintaining the shape of their house. Even though the community migrated to other areas, the built Bugis houses will still reflect Bugis local wisdom. The compliance of the Bugis community is based on a belief in solid cultural values. There is also the character of the Bugis community who will continue to adapt to the surrounding conditions to maintain their "Bugis" identity (Salim et al., 2018). In Lontara, Bugis people consider traditions, not just habits. More than that, tradition or cultural values are a requirement for life according to the phrase "iyya nanigesara' ada' 'biyasana buttayya tammattikkamo balloka, tanaikatonganngamo jukuka, anyalatongi aseya" which means "if tradition is damaged, like palm wine that stops dripping, fish also disappear and rice will not be produced" (BF Mathes, 1969; Salim et al., 2018). These characteristics guide the Bugis community to maintain cultural values while adapting to environmental conditions. Bugis cultural values are driving elements that cause the Bugis tribe to survive as a dynamic society and have strong personalities, including courage, intelligence, religious devotion, and business acumen (Pelras, 1996).

Along with the development of needs, the application of Bugis cultural values in housing has changed due to the adaptation process. This causes a transformation process to form a type of vernacular housing. Vernacular housing is local, domestic, and built using local materials and traditions (Cuthbert & Suartika, 2016; Gusti Ayu Made Suartika, 2013). The Bugis people's behaviour pattern sees their lives as a form of action closely related to cultural values, which are summarized in the concept of "Siri' na Pesse" (Arifuddin, 2016; Hamid, 2003). The concept of "Siri' na Pesse" consists of three values, "Siri'" means self-esteem, which includes the meaning of the nature of the relationship between humans and nature (the environment). "Were" represents the essential character of the Bugis people who like to work and trade. "Pesse" means solidarity or a response to compassion and concern for the environment. "Siri' na Pesse" cultural values are implemented into physical elements that form spatial patterns, spatial units, spatial plans, building units, street patterns, symbolic

elements of buildings, and zoning based on the function and gender of residents (Beddu et al., 2014) (see Table 1).

Table 1. The Meaning and Implementation of "Siri' na Pesse"

|

Meaning |

Implementation | ||

|

Rules/Norms |

• |

Cosmology | |

|

• |

Building orientation | ||

|

Siri' |

The relationship between |

• |

Residential location |

|

humans & nature |

• |

Ornament according to a social level | |

|

Value |

• |

Orthogonal house shape | |

|

Development of self- |

• |

Interesting building shape | |

|

potential |

• |

Tend to choose a prestigious location | |

|

Achievement and creative |

• |

Develop productive homes | |

|

Were |

The balance of human life |

• |

Building work facilities |

|

Value |

Planned & efficient |

• |

Develop multifunctional space |

|

Dignified |

• |

Shops in residential areas | |

|

• |

Zoning for men and women | ||

|

Human values |

• |

Space zoning based on function and level of privacy | |

|

Pesse Value |

Bonding & adhesive family relationships |

• • |

Terrace to strengthen social contact Public space to enhance solidarity and communication links |

|

• |

Placing the location of the house next to | ||

|

The Meaning of Kinship & |

the father's house | ||

|

Brotherhood |

• |

The formation of settlement cluster patterns | |

Source: adaptation from (Akil & Osman, 2017)

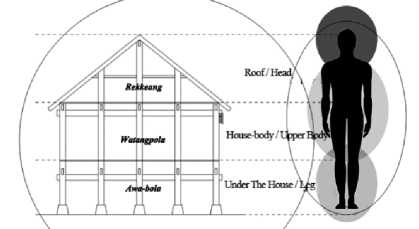

The architecture of traditional Bugis houses is related to spatial planning, especially construction, according to the understanding of vertical cosmology, structure, and other aspects (Abidah, 2016; Arifuddin, 2016; Naing & Iskandar, 2015). The dimensions of the shape and size of the traditional Bugis houses typologies are based on the horizontal anatomy of the human body. The rule is called ‘sulapa eppa' (rhombus quadrilateral), which symbolizes the microcosm of the human body and the universe. Through these rules, the house is divided into the highest part (rakkeang) is for the sacred area, the middle part (watangpola) is for living, and the lower part (Awa bola) is for interaction and the environment (Artiningrum et al., 2019; Naing & Hadi, 2020) (see Figure 1). The interior of a Bugis house consists of spaces (lontang) with an order/arrangement based on the function and level of privacy. The spaces (lontang) usually have a rectangular shape and consist of several parts. In front of the house is a terrace (lego-lego) and stairs that serve as a place to receive guests before entering the house. The first lontang, called lontang risaliweng, is a public area used for living rooms, bedrooms for guests/adult men, and for laying corpses. The second lontang, called lontang ritengnga, is semi-public, usually used for living rooms and bedrooms for parents & newborns. The third lontang, or lontang rilaleng, is private because it is used for the bedroom area of girls (virgins/unmarried) and grandparents (elderly) and a dining room. The back serves as a kitchen, called jokke/jongke. The kitchen position can be separated from the main house, and there are stairs access for women in and out

(Abidah, 2016; Naidah Naing, 2020) (see Figure 2). Another aspect with sacred meaning and is based on cultural values is the roof, namely timpak laja. Timpak laja is an arrangement of roof ornaments that functions as a symbol of the social level of the residents of the house. The arrangement of ornaments consisted of 5 levels for the king's house, 4 for nobles, 2 for the general public, and 1 for enslaved people (Rahim & Abbas, 2021) (see Figure 3).

Figure 1. The Philosophy of the Bugis Phase House Source: Naidah Naing (2020)

Figure 2. The arrangement of rooms in a Bugis house Source: Naing & Hadi (2020)

Figure 3. Overlay only three stacks (left), Overlay only two stacks (right)

The Bugis tribe has essential characteristics that each owns an individual. The characters consist of fundamental values in life that become a reference for the Bugis community. These values are independence, togetherness, openness, awareness, and diversity. That continues to be carried by the Bugis community in every generation. Older people, who first gained knowledge and experience according to the rules of Bugis culture, often become a reserve of wisdom for younger members of the community or family. Through older people, the next generations can learn about the original Bugis cultural rules/values that they can apply to their lives now. According to Mattulada (1985), as in the Lontara script, the Bugis elderly

have an essential role in the inheritance of cultural values in the form of paseng (messages) and pappangaja (parental advice that serves as a guide to life for the younger generation). Over time, the Bugis communities have spread to various regions and adapted to the new environment. This phenomenon caused a cultural shift, which in turn has led to changes in the morphology and shape of the Bugis house based on cultural values. Houses influenced by the environment and specific cultural values are considered vernacular architecture. According to Oliver (1996), the definition of vernacular architecture includes aspects of construction that are built or adapted according to the daily needs of residents at a specific time and place, especially in traditional contexts. The interpretation of vernacular architecture is based on the process of change and adaptation into a new concept with the influence of various meanings and user goals (Asadpour, 2020). The cultural values of the Bugis tribe are still used by the community even though it has been influenced by the times and technology to become a vernacular house.

Method

The focus of this research is to identify and analyze aspects of change that occur in implementing "Siri' na Pesse" values in the attributes and elements of Bugis houses that older people live in with the influence of their cultural characteristics. The context of older people in this research is influenced by their cognitive aspects and original character as "Bugis people". This research uses a mixed method, quantitative and qualitative research. The quantitative method was conducted by distributing questionnaires to determine the basic/general knowledge of the participants (Bugis elderly) on the value of "Siri' na Pesse". Then, the qualitative method is carried out through participant observation and in-depth interviews to explore information from the questionnaire results. This method is also applied to determine the changes in cultural values in the architectural elements and spatial patterns of arrangement of Bugis houses currently lived by older people. This research uses an emic approach (Lucas, 2016) that describes the general meaning of the participant's life experience of a concept or phenomenon (Creswell & Poth, 2016, p. 76). Through this approach, researchers can explore information and data based on the perspective of older people as people who experience the Bugis vernacular house. The results of the two methods are then analyzed descriptively. Furthermore, data collection is based on data on the distribution of Bugis older adults and a purposive sampling system with the snowball method. This research was conducted on the elderly Bugis community in Tolitoli district, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, with the following criteria:

-

1. Man / Woman

-

2. Age > 60 years (Definition of elderly according to UU No. 13 of 1998)

-

3. Native Bugis ethnicity

-

4. Own a house in Tolitoli

Data from the South Sulawesi Family Harmony (Kerukunan Keluarga Sulawesi Selatan /KKSS) of Tolitoli Regency, the dominant types of Bugis are the Bugis Soppeng and Bugis Bone. The range of people with Bugis ethnicity is around 60 – 65% of the total population of Tolitoli (KKSS Chairman, 2023). According to ‘Tolitoli dalam Angka 2021’, the population of Tolitoli is 224,150 people. If viewed from the population composition of the

Tolitoli district in 2020, the number of elderly, including the pre-boomer generation aged 75 years and over, is 1.24%, and the boomer generation aged 56-74 years is 10.32%. It is also known that older people live in most Bugis vernacular houses in Tolitoli. The most significant number of Bugis people are located in the Galang District, with a total of 35,720 people, and the Baolan sub-district, with a total of 67. 600 people (Tolitoli dalam Angka, 2021). Many vernacular houses still dominate both villages. The typology of houses in both villages are mostly still houses and made of wood, generally lived by older people.

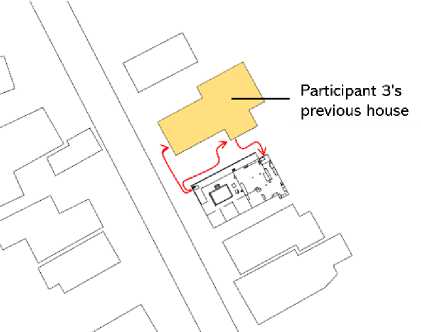

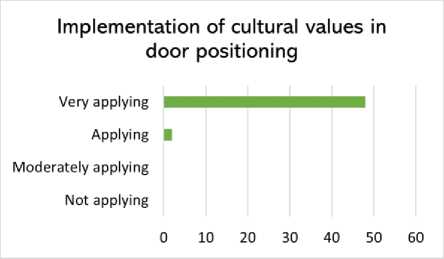

The preliminary phase of the research is conducted quantitatively by distributing questionnaires to 49 respondents in both villages. The questionnaire is based on a literature review. The questionnaire questions contained the respondent's data to ascertain the type of Bugis tribe and regional origin, knowledge/understanding of "Siri' na Pesse" values, and the implementation of cultural values to vernacular housing. Questions about general information of respondents can be filled in manually. The question regarding the understanding/knowledge of cultural values is, "Do you know the cultural values of the Bugis "Siri' na Pesse" (rules in the process of building/designing houses)?" The answer is a checklist box "YES" or "NO". The question of implementing cultural values is, "Are you applying cultural values in the process of building/designing houses at this time?" using a Likert scale answer (1: not applying, 2: moderately applying, 3: applying, 4: very applying). From the results of the questionnaire, several respondents are then selected to become participants in the process of participant observation and in-depth interviews. Communicating with the participants in a more relaxed atmosphere takes longer.

The final phase confirms all data and information from the previous phase by distributing the final questionnaire. The questionnaire contained questions developed from the preliminary questionnaire, the observation process, and in-depth interviews. The final questionnaire was distributed to different respondents from the initial questionnaire. The questionnaire was done on 50 Bugis elderly respondents who live in Malangga and Sandana villages. Thus, it is also necessary to ask questions about the respondent's data to determine the type of Bugis tribe. The form of the question is the level of application of cultural values to the roof shape, wall material, floor material, column material, door placement, space zoning, and the addition of multifunctional spaces in the house. Then, the answers to these questions are a Likert scale (1: not applying, 2: moderately applying, 3: applying, 4: very applying).

Result and Discussion

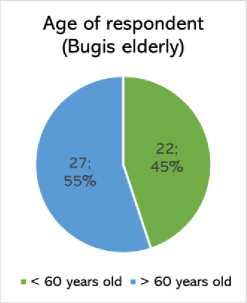

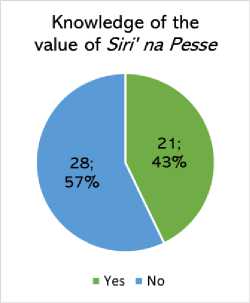

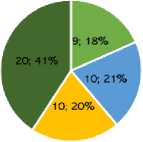

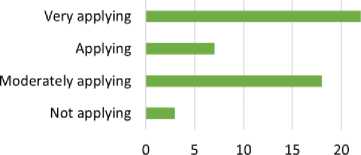

Questionnaires are distributed to 49 respondents from various regions in the Tolitoli district. Some participants did not fulfil the respondent's age criteria, so they could not proceed to the observation and interview phases. 22 out of 49 respondents are under 60, and 27 others are aged 60 – 92 (see Figure 4). Regarding knowledge/understanding of "Siri' na Pesse" cultural values, 28 out of 49 respondents did not know the term "Siri' na Pesse". In contrast, 21 others answered that they knew (see Figure 5). Then, for applying cultural values to housing, nine respondents answered not applying, ten moderately applying, ten applying, and twenty others very applying (see Figure 6).

Figure 4. Age of the respondent

Figure 5. Knowledge of Siri’ na Pesse

The level of application of Siri' na Pesse cultural values in Bugis vernacular housing

L Not applying ■ Moderately applying

Applying "Veryapplying

Figure 6. Level of implementation of "Siri' na Pesse"

Therefore, it is necessary to select a respondent or participant who is more in line with the criteria of age and aspects of cultural values that are better understood or more visible in their implementation to the house. The KKSS data shows two villages with the most Bugis people, especially older people who still lived in vernacular houses, Malangga and Sandana villages. Bugis vernacular houses still use the typology of stilt houses (same as traditional houses) and wood materials. The determination of participants is carried out through the snowball sampling method and the suitability of the participant criteria. Six participants were selected for participant observation and in-depth interviews, consisting of four female and two male participants. All six participants came from Bugis tribes such as Bugis Soppeng, Pinrang, and Bone.

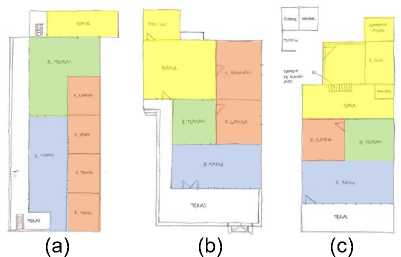

Based on observations and in-depth interviews with six participants, the application and changes in attributes, elements, patterns, and spatial arrangements in vernacular houses are discussed based on the three, namely Siri', Were, and Pesse. Previously, a pre-mapping process was used to identify the typology, material, shape, and spatial arrangement pattern in the research location. This process aims to classify and determine the type of Bugis vernacular house typology that will be studied and observed in this research. The main factor in the classification process is how the patterns and spatial arrangements are formed in the participant's vernacular house based on the influence of the implementation of understandable cultural values. The structure of zoning and spatial arrangements can be explored using semiotic theory by Saussure. Semiotics is used to look at settlement patterns from the aspects of space, form, spatial organization, community beliefs, functions, and activities (Chandler, 2002; Kerong, 2015). The theory can be supported by spatial theory. Spatial theory is used to look at the functional aspects of the division of space and the functions and activities within it. The building's expression of form and supporting elements are also considered aspects (Kerong, 2015). Regarding the typology, material, and shape of the house, almost all people living in the two villages have a typical type of house on stilts with wooden material and a rectangular house building shape with various roof shapes. Therefore, two types of vernacular houses in the two villages are determined: Type A and Type B. In Type A, the guest room and living room are lined up straight along one side of the house's wall. Instead, Type B features a layout where the bedrooms are distributed around

both sides of the house's wall, creating a non-linear relationship between the living area and other rooms like the guest room. (see Figures 7 & 8).

Public area (Iontang risa!iweng)

Semi-public area (Iontang ritengnga)

Figure 7. Type A vernacular house (a) Participant 1&2, (b) Participant 4, (c) Participant 5

Private area (Iontang riialeng)

Service area (jongke)

(a) (b)

Public area (Iontang risa!iweng)

Private area (Iontang riialeng)

Service area (∕ongke)

Semi-public area (Iontang ritengnga)

Figure 8. Type B vernacular house (a) Participant 3, (b) Participant 6

Regarding the level of privacy, both types of vernacular houses still apply cultural rules in a spatial arrangement, i.e., the difference is the position of the room or space. In terms of building materials for both types, wood is still used in almost the entire body of the building, but in some cases, the kitchen and bathroom areas use a concrete material. According to the criteria for classifying the participant's house type, the main focus is the pattern and arrangement of the interior space. It ignores the exterior areas, such as the terrace and the position of the stairs. The six participant houses have terraces and staircases that are different from each other. The following discussion explains the values of Siri', Were, and Pesse in vernacular housing.

The implementation of cultural values based on Siri' values is in the form of spatial and house orientation rules, the shape of the house, which includes the use of materials and the placement of elements, as well as the use of elements to indicate social level. Based on basic rules in Bugis cultural values, the direction or orientation of the house is recommended to face south or west. Both directions are considered good directions. Only five of the six participants were oriented according to the rules, and the other five did not apply. Participant Five's house faces west, and the other participants face west-southwest, north, and eastnortheast. According to participants whose houses do not comply with the rules regarding

cultural values, it is due to the environmental conditions that have been arranged so that they only follow the flow of existing settlement arrangements.

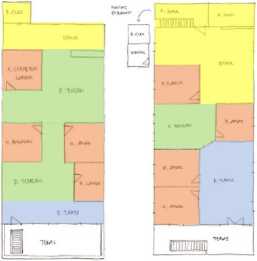

In the rules for placing doors, if rooms are facing each other, especially bedrooms, the position of the door should not have a position that is directly opposite. If the condition of the house is with the position of the door like that, it is recommended that one of the rooms is not used as a bedroom because it is believed to endanger the room's occupants, such as becoming sick often. This case occurred at Participant 3's house, so he changed the function of one of the rooms into a clothes storage room (see Figure 9).

"…this used to be the fault of the craftsmen, so the position of the doors is facing like this. Older adults said the door's position like that could make the room owner sickly. Therefore, I only use one of these rooms for storing clothes" – Participant 3 (20/02/2023)

Figure 9. The position of the door is not according to the rules

Two elements symbolize the social level in the Bugis community: the roofs and stairs. The top of the house is the place that has the highest degree, so it is likened to the position of the head on the human body. The results of observations on participants, 1 out of 6 participants still applies the rules of cultural values, which is the shape of a gable roof. The element that shows the level of the social status of the house's residents is the roof ornament arrangement, or what is called timpa laja. From the results of in-depth interviews, the six participants understood and knew the cultural values but did not apply them. The reason is that they are not from a family with a high social level, and adding these ornaments requires quite an expensive fee. Thus, Bugis people with a high social level strictly adhere to the rules for using these ornaments.

In the context of the Bugis community in Malangga village, they put aside the rules of the roof shape, but they prioritize the use of the roof to help their activities as farmers/planters. They transformed the shape and system of the roof for drying and storing crops such as cloves and cocoa. The roof system they created can be opened and closed manually with the help of a rope hook. Both sides of the roof rest on the house's walls, and there are hinges on each side, and the summit of the roof is made like a knob so that when it rains, water does not enter the drying/ceiling area. Access to the drying area uses a stair made permanent by the house owner during construction (see Figures 10 & 11).

Figure 10. View of the roof when open

Figure 11. The process of opening the roof

In the aspect of the stairs, according to the 6 participants, the ladder model, which symbolizes the social level of residents, is an L-shaped staircase or has two directions in one stair. Based on the observation results, none of the six participant houses used the ladder model. Again, this is due to adherence to the rules of cultural values, i.e., only people with a high social level can use the model. Therefore, the participants only used the one-way staircase model for access in and out of the house.

"… it's rare for people to use this type of ladder except for the homes of people with high social levels. Now the use of this ladder model is used not for residential homes but for houses such as villas" – Participant 8 (04/02/2023)

The implementation of the Were value is in the form of a representation of the individual character and behaviour of the Bugis community, which is to make a business or trade. The implementation of this value is the existence of a specific area or space created to accommodate these activities. Usually, the Bugis community does not immediately provide the room at the beginning of house construction. Still, it only provides an empty area on the terrace, front yard, or under the house. If the space provided for storage needs or other activities is located under the house, then since the beginning of construction, the house's height is higher at the bottom so that residents can move comfortably according to their height.

"Since a long time ago, when I was taught how to build a house on stilts by my parents, it was suggested that if you make a house under the house, it should be the same or higher

than the height of the owner/occupant of the house so that you don't bump into it when you enter it hahaha…" – Participant 8 (04/02/2023 )

In Participants 1 and 2 houses, the area under the house stores garden products such as coconuts, bananas, and firewood and even raises chickens. It is also used as a garage for vehicles belonging to residents or visiting guests. Participants 3 and 6 are under the house for business activities, such as making stoves, brown sugar, and furniture (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Utilization of space under the house

The value of Pesse refers to human values and as a binding relationship between families. The meaning of human values is the pattern and arrangement of the house according to basic human norms, such as zoning according to gender, function, and level of privacy. Then, the meaning of the binder of family relationships is how patterns and spatial arrangements can improve relations between family members. An example is the living room used for gathering or the position of the parent's and children's houses that are close together. The zoning division for male and female areas refers to the division of space based on the space's function and level of privacy. The more forward-positioned the space is, the more public its function is, often reserved for men only. The activities carried out by men are more related to public activities, and women do more private activities. Public spaces include the terrace and living room, and semi-public to private spaces include the living room, bedroom, and kitchen. In this study, the participants' homes generally still apply these rules, the difference only in the position of the space, especially the bedroom. The differences in spatial patterns and arrangements were classified into Type A and Type B. On average, the implementation of adhesive values or binding between families in the eight participants used the living room as a gathering area, especially for close families. The living room is often used to receive guests close to the house owner. That is supported by the basic attitude of the Bugis people, who are friendly and open to various people from various backgrounds. In this regard, the Bugis community also has a value system related to the house's proximity between families. Participants 1 and 2 still apply this matter, as evidenced by the position of older people (participant) homes close to or directly connected to the children's homes (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Location of the houses of participants 1 & 2 (mother & child)

In the final questionnaire, the questions regarding the implementation of cultural values to elderly Bugis vernacular houses are divided into several types of questions that are more specific to architectural elements, such as the level of implementation of cultural values to roof shapes, wall materials, floor materials, column materials, door placement, space zoning, and the addition of a multifunctional space in the house. The question points are based on the type of implementation of cultural values from literature and lontara studies, as well as the results of in-depth interviews. The results of the question regarding the level of implementation of cultural values in the shape of the roof, the majority of respondents, as many as 29 people, answered very applying; 11 moderately applying, six applying, and four did not apply (see Figure 14). On the level of implementation of cultural values to wall materials, as many as 40 respondents answered very applying; five moderately applying, three applying, and two did not apply (see Figure 15). Regarding the level of implementation of cultural values to floor materials, 44 respondents answered very applying, five moderately applying, and one answered applying (see Figure 16). Questions about the level of implementation of cultural values in the column material, as many as 44 respondents were very applying, five moderately applying, and one did not applying (see Figure 17).

Implementation of cultural values on roof shape

Veryapplying ^^^^H^^^^H

Applying ^^M

Moderatelyapplying ^^H

Not applying ^H

0 10 20 30 40

Implementation of cultural values in wall materials

Vervapplying ^^^^M^^M^^^B^H

Applying M

Moderately applying ■

Not applying ■

0 10 20 30 40 50

Figure 14. Implementation of cultural values to the shape of the roof

Figure 15. Implementation of cultural values in wall materials

Implementation of cultural values in floor materials

Very applying ^^^^^^^^^^^^H

Applying M

Moderatelyapplying ∣

Not applying

O 10 20 30 40 50

Implementation of cultural values in column materials

Veryapplying ^^^^^H^^^H^^^H^^^∣

Applying M

Moderately applying

Notapplying I

0 10 20 30 40 50

Figure 16. Implementation of cultural values in floor materials

Figure 17. Implementation of cultural values in column materials

Regarding implementing cultural values to the door placement, 48 respondents very applying it, and two respondents applied (see Figure 18). For questions about zoning space, as many as 22 respondents answered very applying, seven applying, 18 moderately applying, and three did not apply (see Figure 19).

Figure 18. Implementation of cultural

values in the placement of doors

Implementation of cultural values in space zoning

Figure 19. Implementation of cultural values in spatial zoning

Then, regarding the question about implementing cultural values in the addition of multifunctional spaces, as many as 19 respondents were very applying, seven were applying, nine were moderately applying, and 15 were not (see Figure 20).

Implementation of cultural values in multifunctional space

Figure 20. Implementation of cultural values in the addition of multifunction space

Most older people Bugis in the two villages have almost the same level of implementation of cultural values. Regarding implementing cultural values to the shape of the roof, most respondents apply it. However, the form of the question is still not specific, whether it refers to a state that symbolizes a social level, such as the basic rules of Bugis cultural values, or is

it just a form commonly used in Bugis house. Thus, this answer cannot be classified as an answer for fully implementing cultural values. When asked about materials for walls, floors, and columns, almost all respondents answered they were very applying. According to respondents, wood materials in their current house are sufficient to represent Bugis houses, although they do not use materials suitable with lontara. It is the same with applying values to door placement. The majority of respondents answered that they very apply.

Regarding spatial zoning, the respondents are divided between those who are very applying and those who are moderately applying. Some respondents are no longer too concerned about zoning based on gender. Most respondents are more flexible towards guests considered familiar and close to being allowed into the semi-private space. Then, to add multifunctional space, respondents are divided into two dominant groups: very applying and applying. Respondents who apply the average are Malangga village residents who work as gardeners, so they need more additional space for processing or storage. Meanwhile, respondents who answered that they moderately applied made multifunctional space only limited to the need for storing goods and garages.

From the condition of older people living in the vernacular house, implementing the cultural value of "Siri' na Pesse" in occupancy is not as strict as in the past. That was influenced by environmental conditions and habits that began to change in the daily lives of older people. Another thing that also affects is the level of comfort experienced by older people in the current housing, which is considered sufficient to meet the needs and conditions of older people in the house so that cultural values considered not crucial are no longer used or applied.

Conclusion

In implementing Bugis cultural values, the initial phase distributed an initial questionnaire based on a literature review. From the questionnaire results, the answers regarding implementing Bugis cultural values applied by the participants are not identified clearly and in detail. Therefore, observation and in-depth interviews are needed to determine what aspects/cultural values have changed or are still applied in vernacular houses. The results of this phase show that several value rules are no longer applied, but there are also values still used today. Several participants did not apply The rules of value, which are Siri' values that concern aspects of spatial orientation and house building, the use of materials, and the use of architectural elements to symbolize the homeowner's social level. In terms of spatial orientation and house building, this cannot be applied due to the environmental conditions of the settlements, which already have a specific pattern, so homeowners must follow the existing ones. If the house's orientation does not follow the rules of cultural values, then the spatial orientation is still implemented during construction.

Regarding using materials, almost all participants no longer applied them due to the unavailability of bitti and ipiq wood materials, which are usually used in traditional Bugis houses in the Tolitoli area. The Bugis community in Tolitoli then switched to using affordable and readily available materials, but with a quality that is quite the same as the type of material in the rules of cultural values. Then, for the aspect of using architectural

elements as symbols of social level, some Bugis people in Tolitoli rarely apply this. That's because the cost of making elements such as timpa laja (roof arrangement ornaments) is quite expensive. People in areas where most of the population are planters/farmers prefer to utilize the roof to support activities such as drying or storing crops. This need has triggered the community to innovate in the form of a roof that can be opened and closed to make it easier for them to control the drying of crops. Other aspects of cultural values contained in the Were and Pesse values were still sufficiently applied by the eight participants. However, this is because applying this value does not require complex materials to use/apply, so they only need to adjust to the conditions of the settlement and residential environment. Regarding understanding cultural values, several participants have conducted in-depth interviews and stated that they understood these values, but only in the form of points such as taboos/prohibitions, without knowing the goals and benefits of implementing these values.

Reference

Abidah, A. (2016). Applying Uneven Number (Te’gennebali) of Certain Elements in Bola Ugi District of Soppeng South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Procedia Engineering, 161, 810– 817.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.717

Akil, A., & Osman, W. W. (2017). Bugis Local Wisdom in the Housing and Settlement Form: An Architectural Anthropology Study. Lowland Technology International, 19(1), 77–86.

Arifuddin. (2016). Cultural and Needs–based Housing Development Case Study: The Bugis Community in Makassar City. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 227(November 2015), 300–308.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.075

Artiningrum, P., Sudikno, A., & Arif, K. A. (2019). Adaptation Patterns of Bugis Diaspora Village Architecture: Sulapa Eppa’ Philosophy and Function-Form-Meaning-Context Theory. ISVS E-Journal, 6(4), 49–54.

Asadpour, A. (2020). Defining The Concepts & Approaches in Vernacular Architecture Studies. National Academic Journal of Architecture, 7, 241–255.

B. F. Matthes. (1969). Over de Ada’s of Gewoonten der Makassaren en Boegineezen. New York: Doubleday Company Inc. 1969.

Beddu, S., Akil, A., Osman, W. W., & Hamzah, B. (2014). Eksplorasi Kearifan Budaya Lokal sebagai Landasan Perumusan Tatanan Perumahan dan Permukiman Masyarakat Makassar. Prosiding Temul Ilmiah IPLB, 7–12.

http://eng.unhas.ac.id/arsitektur/files/5ae0ad4fceba7.pdf

Chandler, D. (2002). Semiotics: The basics. Routledge.

Chonody, J. M., & Teater, B. (2018). Aging and Ageism: Cultural Influences. Social Work Practice With Older Adults: An Actively Aging Framework for Practice, 23–54.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506334271.n2

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage publications.

Cuthbert, A. R., & Suartika, G. A. M. (2016). The Vernacular Hiatus: Modernity, Tradition, and Ethnicity. RUANG: Jurnal Lingkungan Binaan (SPACE: Journal of the Built Environment);3(2).

https://doi.org/10.24843/JRS.2016.v03.i02.p02

Farage, M. A., Miller, K. W., Ajayi, F., & Hutchins, D. (2012). Design principles to accommodate older adults. Global Journal of Health Science, 4(2), 2–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v4n2p2

Gusti Ayu Made Suartika. (2013). Vernacular Transformation, Architecture, Place and Tradition (1 ed). Pustaka Larasan.

Hamid, A. (2003). “Siri’ Butuh Revitalisasi”, dalam Siri’ dan Pesse, Harga Diri Orang Bugis, Makassar, Mandar, Toraja, ed (M. Yahya (ed.)). Pustaka Refleksi.

Kerong, F. T. A. (2015). Relasi Struktur Masyarakat dan Tata Zonasi Permukiman Adat di Desa Nggela, Ende-Flores. ATRIUM - Jurnal Arsitektur, 1(1).

https://doi.org/10.21460/atvm.2015.11.8

Koentjaraningrat. (2011). Pengantar Ilmu Antropologi Jilid I. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta.

Lang, J. (1987). Creating Architectural Theory. The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental. Design.

Lucas, R. (2016). Research Methods for Architecture. Laurence King Publishing Ltd.

Mattulada. (1985). Latoa: Suatu Lukisan Analisis terhadap Antropologi Politik Orang Bugis. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Meutia Farida Hatta, S. (1989). Proses Menua di Barat dan Timur: Suatu Tinjauan Antropologis. Seminar Sehari Tentang Usia Lanjut Oleh Pusat Pengembangan Psikiatri Dan Kesehatan Jiwa.

Na, J., Huang, C. M., & Park, D. C. (2017). When Age and Culture Interact in an Easy and yet Cognitively Demanding Task: Older Adults, but Not Younger Adults, Showed the Expected Cultural Differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(MAR), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00457

Naidah Naing, S. T. (2020). Vernacular Arsitektur: Perspektif Anatomi Rumah Bugis (Sulawesi Selatan): Bintang Pustaka.

Naing, N., & Hadi, K. (2020). Vernacular Architecture of Buginese: International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, 8(3), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.8.3_1

Naing, N., & Iskandar, B. P. (2015). Model of Settlements Float Management based on Local Wisdom for Disaster Mitigation in Tempe Lake - Indonesia. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 10(21), 42329–42335.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and Systems of Thought: Holistic versus Analytic Cognition. In Psychological Review (Vol. 108, pp. 291–310). American Psychological Association.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291

Oliver, P. (1996). Vernacular Studies: Objectives and Applications. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 8(1), 12-12.

Park, D. C. (2002). Aging, Cognition, and Culture: a Neuroscientific Perspective.

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 26(7), 859–867.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00072-6

Pelras, C. (1996). The Bugis; The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific. Great Britain: Blackwell Publishers (vol. 53, issue 9).

Rahim, M., & Abbas, I. (2021). Characteristics of Buginese Traditional Houses and their

Response to Sustainability and Pandemics. E3S Web of Conferences, 328. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202132810015

Rapoport, A. (2005). Culture Architecture & Design (p. 137).

http://egyptarch.gov.eg/sites/default/files/pdf/Books/Culture Architecture&Design.pdf Salim, A., Salik, Y., & Wekke, I. S. (2018). Pendidikan Karakter dalam Masyarakat Bugis.

Ijtimaiyya: Jurnal Pengembangan Masyarakat Islam, 11(1), 41–62.

https://doi.org/10.24042/ijpmi.v11i1.3415

UNICEF. (2021). Defining Social Norms and Related Concepts. Unicef, 1–4.

Van Quaquebeke, N., Graf, M. M., Kerschreiter, R., Schuh, S. C., & van Dick, R. (2014). Ideal Values and Counter-ideal Values as Two Distinct Forces: Exploring a Gap in Organizational Value Research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(2), 211–225.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12017

William, J. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. New York: Henry Holt and Company the Principles of Psychology.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11059-000

222

SPACE - VOLUME 10, NO. 2, OCTOBER 2023

Discussion and feedback