Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting

on

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis

Vol. 17 No. 1, January 2022

AFFILIATION:

1 Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Udayana, Indonesia

*CORRESPONDENCE: putu.ardiana@unud.ac.id

THIS ARTICLE IS AVAILABLE IN:

DOI:

10.24843/JIAB.2022.v17.i01.p01

CITATION:

Ardiana, P. A. (2022) Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 17(1), 1-21.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received:

17 October 2021

Revised:

31 December 2021

Accepted:

7 January 2022

Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting

Putu Agus Ardiana1*

Abstract

A plethora of studies reveal that stakeholder engagement is critical in sustainability reporting. However, there is a paucity in the literature on how stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting may lead to more meaningful sustainability reports. This paper aims to conceptualise the role of stakeholder engagement in producing more meaningful sustainability reports. This conceptual paper offers avenues for future empirical research. This paper contributes to the literature and the theory by shedding light on the importance of institutional work in shifting the institutional logic of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting from a strategic management tool to an accountability mechanism so that more meaningful sustainability reports are produced. Stakeholder engagement allows the reporting companies to become more aware of sustainability issues that are informed by their stakeholders while the engaged stakeholders also benefit from the information provided by the reporting companies on the issues, agenda, and performance related to sustainability.

Keywords: stakeholder engagement, sustainability reporting, neo-institutional theory

Introduction

The objective of this paper is to conceptualise the important roles of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting in order to promote more meaningful sustainability reports for both the preparers and the readers. Prior studies reveal that stakeholder engagement is a crucial element of sustainability reporting (see, for example, Bellucci et al., 2019; Kaur & Lodhia, 2018). However, there is a paucity in the literature on how stakeholder engagement can contribute to the production of more meaningful sustainability reports. The meaningfulness of sustainability reports has become a critical issue because the reporting arguably tends to contain self-serving bias or self-laudatory in nature (Keusch et al., 2012). To some extent, the report is arguably manipulative (Hahn & Lülfs, 2014), camouflaging (Michelon et al., 2016), and even a simulacrum (Boiral, 2013). Therefore, reporting companies are expected to identify and engage with their stakeholders to produce more meaningful sustainability reports in the sense that the sustainability information provided in the report may meet the expectations of stakeholders from such engagement otherwise it will only be about luck (Rinaldi et al., 2014).

The essence of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting is communication or dialogue between a reporting company and its relevant stakeholders (AA1000, 2015; GRI, 2016; Kaur & Lodhia, 2018). Engaging with stakeholders allows the reporting company to improve its business process, while the engaged stakeholders are also informed regarding the company’s sustainability issues, agenda, and performance (AA1000, 2015; Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2018; GRI, 2016). This paper responds to a call for conceptualising the complexity of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting which lays in a continuum of two ends, i.e., as a strategic management tool and an accountability mechanism (Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, 2021; Rinaldi et al. 2014).

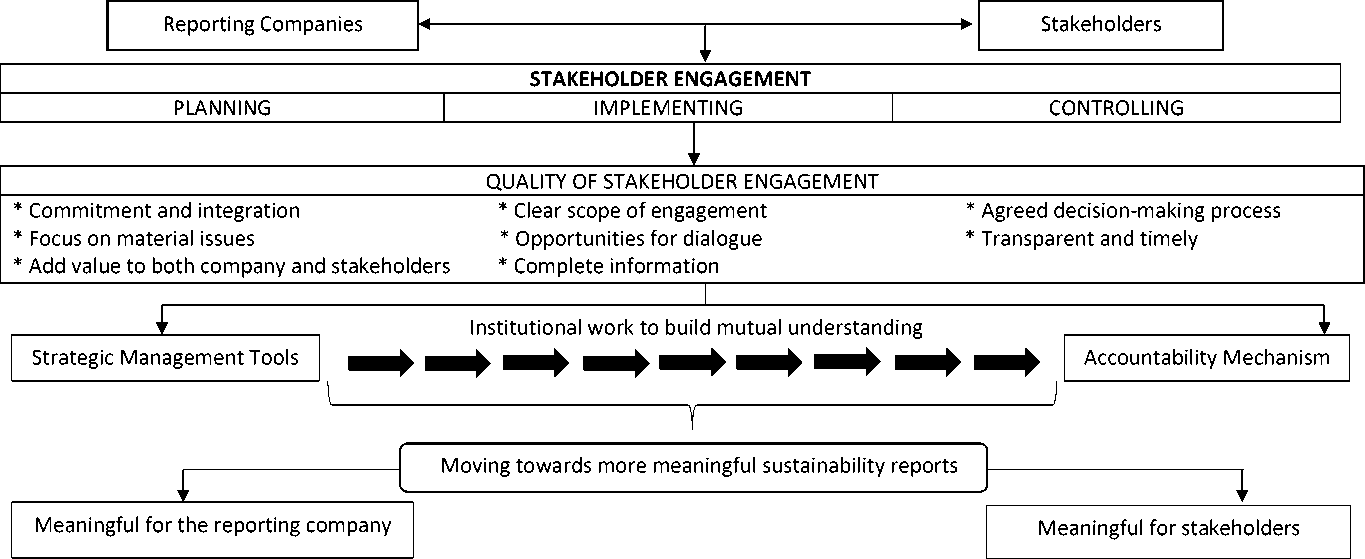

This paper conceptualises that stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting is an ongoing process of planning, implementing, and controlling a dialogic engagement between a reporting company and its stakeholders. More specifically, for an engagement with stakeholder to be able to contribute to a more meaningful sustainability report (i.e., one which adds value for both the reporting company and its stakeholders), the reporting should be based on a continuous clear-scope dialogic and agreed decision-making process with stakeholders on recent material sustainability issues (AA1000, 2015). The reporting company along with its stakeholders should have strong commitment to integrate sustainability issues into the company’s strategy, governance, and operation and disseminate the agreed sustainability topics into its sustainability report transparently (Bellucci et al., 2019). This conceptual paper follows Smith et al. (2011) in that It goes beyond merely reviewing the extant literature. It offers a conceptual framework for future empirical studies in the field of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting by reviewing the extant literature and making reference to sustainability reporting frameworks and neo-institutional theory. A plethora of studies using the theory assumes that institutions are taken for granted leading to stable and isomorphic (similar) practices (see, for example, (Fitriasari & Kawahara 2018; Yusoff et al., 2019). This conceptual paper conceptualises an institutional work in the field that strives to disrupt an old institution (the conception where companies engage with stakeholders by informing them about the companies’ sustainability issues) and replace it with the new one (the conception where stakeholders are engaged in dialogue to solve sustainability issues and define sustainability report content). From this, stakeholder engagement can produce more meaningful sustainability reports.

This paper offers both practical and theoretical contributions. Firstly, it offers a conceptual framework that can be used as guidance for empirical research in the field of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting using the neo-institutional theory. Secondly, it sheds light on how stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting should be institutionalised for a more meaningful report towards a taken-for-granted accountability mechanism to stakeholders. Lastly, it offers practical contribution for reporting companies through an increasing awareness about the importance of stakeholder engagement not only for their business process but also for producing more meaningful information in sustainability reports. Equally important, it also increases the awareness of stakeholders about companies’ sustainability issues, agenda, and performance by taking a part in variety of engagement mechanisms.

This paper is structured as follows. The next two sections review the underpinning theory and define what stakeholder engagement really is respectively. The following section conceptualises a model of stakeholder engagement in sustainability

reporting towards more meaningful sustainability reports. The last section concludes this paper and outlines avenues for future empirical research utilising the proposed model.

Neo-Institutional Theory as the Underpinning Theory. Neo-institutional theory views stakeholder engagement as a relational space (Wooten & Hoffman, 2013) where actors in a reporting company interact with other actors (i.e., stakeholders). They interact with one to another for collective understandings (Scott, 2014) about the company’s sustainability issues and decide what material topics should be included in the sustainability report. The presence of new economic, social, and/or environmental issues, for example, would be a disruptive event for the existing collective rationality among the field members (actors in the company and stakeholders) (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting constitutes relational space in which idea contestation with conflicting arguments and views are resolved and a new collective rationality is developed by field members (Thornton et al., 2012). Actors would try to persuade, build mutual awareness, and gain admittance by challenging the existing collective rationality among field members. Once they receive support from the field members, the existing collective rationality would be altered, and new collective understandings would arise in the field. During the process of idea contestation, field members may respond to it differently from adoption to adaptation (Oliver, 1991). Heterogeneity, variation, and change in the field of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting indicate dynamic process of institutionalisation of the field over time (Scott, 2014).

The perceived meaning of an organisational field refers to institutional logic through the neo-institutional theory lens. Thornton & Ocasio (2008) define institutional logic as “the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences”. Further, Thornton et al. (2012) convincingly argue that institutional logics account for the dynamic both material (structure and practice) and symbolic (ideation and meaning) elements of every institutional order in society. Research in institutional logics shows dialectic tension between competing logics underlying an institutional order (Ocasio et al., 2017). For example, Marquis & Lounsbury (2007) examined about community logic versus market logic in banking sector while Dunn & Jones (2010) studied about professional logic versus science logic in medical education.

The current structure and practice in the field are influenced by a dominant logic among the other competing logics (Thornton et al., 2012). The current dominant logic may be shifted or replaced by the other competing logics such as institutional environment and the interpretation of meanings among actors may change over time (Marquis & Lounsbury, 2007). For example, , Thornton & Ocasio (1999) find a shift from editorial logics to market logics in the field of higher education publishing. Dynamic change in institutional logics would make institutions never able to get fully institutionalised. Institutionalisation is not an end point but an on-going process because actors, interests, and interpretation of meanings may change across time hence understanding meanings in local context are critical not only to the initiation of institutional change but also to its continuous maintenance (T. B. Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006).

Institutional logics help explain how institutional entrepreneurs interpret social or cultural meanings and challenge the meanings with other actors in a relational space (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008; Wooten & Hoffman, 2013). Hardy & Maguire (2013) state that institutional entrepreneurs play an important role in framing an idea and engaging in competing logics. Therefore, institutional entrepreneurs should have the ability to discover idea, communicate the idea, and convince others to manipulate institutions through shifting institutional logics from existing logic to the new one (Thornton et al., 2012). Entrepreneurial actors should have the power to mobilise resources and the ability to engage in contestation in meanings and practices (T. B. Lawrence, 2008)

Institutional entrepreneurship is a juxtaposing notion leading to a paradox of embedded agency (Garud et al., 2007). On the one hand, institutions have been believed as taken-for-granted social facts with socially and culturally embedded understandings that provide specification and justification for social arrangements and behaviours towards stability and continuity (Hardy & Maguire, 2013). On the other hand, entrepreneurship expect changes in the existing rules, norms, and beliefs, instead of continuity (Garud et al., 2007).

The paradox of embedded agency in institutional entrepreneurship gives rise to two concerns (Hardy & Maguire, 2013). Firstly, it is unclear that actors who are embedded in the existing institutional arrangements, and have been given advantages by it, are able to generate novel ideas for institutional change. Dominant actors who hold dominant resources which are needed for transformation of institutions usually have been deeply embedded in—and given advantages by—the existing institutions and therefore they might not be able to come up with novel ideas of institutional transformation. Secondly, it is also unclear that the desired actors for institutional change are able to persuade other actors in the organisational field to institutionalise new practices. The desired actors for change are usually peripheral actors, i.e., those who are not deeply embedded in and benefiting from the existing institutions and have relatively little power and resources to promote change by realising their novel ideas. Entrepreneurial actors who initiate institutional change can be individual actors (Dew, 2006), or collective actors, such as organisations (Déjean et al., 2004), professions (Greenwood et al., 2002), and associations (Demil & Bensédrine, 2005).

Institutional entrepreneurship may arise in any possible state of organisational field (Hardy & Maguire, 2013). However, a plethora of studies (Child et al., 2007; Greenwood & Suddaby 2006; Maguire et al., 2004) find that emerging fields and those in crisis are likely to have greater opportunity for institutional entrepreneurship for two reasons. First, emerging organisational fields are indicated by lack of institutionalised practices that becomes a stimulus for entrepreneurial actors to solve problems. Second, organisational fields which are experiencing crisis often show disruptive events with ambiguities and pressures up to the surface hence uncertainty, tensions, and contradictions in the crisis fields may become another stimulus for institutional entrepreneurs to initiate institutional change.

Instead of focusing on who the institutional entrepreneurs or actors shaping the institution are, institutional work focuses on the actors’ actions because the central of institutional dynamic is the actions undertaken by institutional entrepreneurs (Lawrence et al. 2013; Lawrence et al., 2009). T. B. Lawrence & Suddaby (2006) define institutional work as “the purposive action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions”. There are at least two overlooked issues in

institutional work as identified by Lawrence et al. (2013). First, institutional work is not only about successful purposive actions in shaping institutions that may include unplanned consequences. Secondly, cognitive and emotional aspects of actors engaged in institutional work are equally as important as their skills and expertise, hence reflexive dimension (i.e., actors’ beliefs and attitudes) in institutional work is very fruitful to study.

Stakeholder Engagement Defined. Stakeholder engagement is an interactive relationship between an organisation and its stakeholders in which stakeholders are viewed as “a source of value and competitive advantage” for the organisation (A. T. Lawrence & Weber, 2014). The importance of stakeholder engagement is in line with the principle of “stakeholder inclusiveness” (GRI, 2016) or “stakeholder inclusivity” (AA1000, 2015) in that the reporting companies should be able to identify who their stakeholders are and how the expectations and interests of those stakeholders are met.

The basis for determining stakeholders may vary amongst reporting companies. Mitchell et al. (1997), for example, develop a model of stakeholder salience in order to determine which stakeholders the company should focus on based on three attributes, namely stakeholder’s power, legitimacy, and urgency. The more attributes the stakeholders have, the more salient those stakeholders are. Meanwhile, stakeholder engagement approaches could take on various forms (Gao & Zhang, 2006), such as passive engagement, listening engagement, limited two-way process engagement, and active engagement. Indeed, stakeholder engagement is a crucial point in sustainability reporting (Manetti & Bellucci, 2016) because it may facilitate the quality of reporting (KPGM, 2015) and completeness of the report (Adams, 2004). For being accountable to stakeholders, the purpose of stakeholder engagement should be upgraded from only developing knowledge and understanding to addressing sustainability concerns as expected by stakeholders (Bebbington et al., 2007).

In every effort to address sustainability issues, companies should be open to criticism from stakeholders (Hörisch et al., 2015). Ideally, there should be a platform to facilitate wider debate—not only about criticism from stakeholders which demands for quick response by company—but also debate among different stakeholder groups (Unerman & Bennett, 2004). However, not all companies are ready for such a situation. Several companies choose to provide internet-based platforms for stakeholder engagement with internally-generated contents (Rinaldi, 2013). Reputational risk management over unsustainable practices becomes an important consideration of managers in designing stakeholder engagement, as noticed by Dillard & Yuthas (2013) and Ardiana (2019).

Among scholarly works on stakeholder engagement, there are at least two broad perspectives on stakeholder engagement, namely strategic and holistic views (Rinaldi, 2013). The strategic perspective focuses on engagement with relevant stakeholders, e.g., those with have power, legitimacy, and urgency (Mitchell et al., 1997) to a company’s economic, social, and environmental issues. Companies according to this view consider stakeholder engagement as a strategic management tool for improving their competitive position (marketing tool), warding off stakeholder challenges (social tool), and/or reducing political pressure and regulation (political tool). In contrast, the holistic perspective views stakeholder engagement as an accountability mechanism for companies with regard to sustainability issues to all stakeholders, of which the engagement should be based “long-term, open, and mutually respectful relationship”

(Rinaldi, 2013). In other words, companies should not be benefiting one stakeholder group (e.g., financially-powerful stakeholder groups) while harming another group (e.g., local communities) but be open to stakeholder criticism for improvement of internal business process because building their reputation requires support from multiple stakeholder groups inclusively.

(Rinaldi, 2013) and Rinaldi et al. (2014) suggest that strategic and holistic views of stakeholder engagement are two opposite camps, of which the holistic view is the very ideal condition of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting. In practice, they found that stakeholder engagement practices lay along a continuum between these two opposite ends. Extra efforts should be undertaken over time by companies to shift the practice of stakeholder engagement towards the ideal level of accountability to all stakeholders.

Research Method

Adapting literature review papers by Curtis & Mont (2020) and Geissdoerfer et al. (2018) in wider sustainability topics, this paper reviews the literature on stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting. Key publications being reviewed were those listed on the Academic Journal Guide 2021 level 3 and above, published between 2011 and 2020 with keywords “stakeholder engagement” and “sustainability reporting”. They are reputable peer-reviewed journals ranked by the Chartered Association of Business School (Guide, 2021). Appendix 1 shows the list of the key publications. Following Paul & Criado (2020), the ten-year period between 2011 and 2020 was determined to be able to undertake a systematic literature review leading to the conceptualisation of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting.

Since this paper is a conceptual paper, it goes beyond merely reviewing the extant literature (the key publications shown in Appendix 1). In conceptualising stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting, this paper also makes reference to sustainability reporting frameworks. The neo-institutional theory was chosen to illuminate the idea that an institution is not necessarily taken for granted and stable – it can be questioned and replaced by a new institution. Institutional entrepreneurs come with a new institution to challenge the status quo. Their institutional work strives to disrupt the existing institution and replace it with the new one. The dynamic nature of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting and how it can bring significant changes to both the reporting organisations and stakeholders can be illuminated by the neo-institutional theory.

Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting Towards More Meaningful Sustainability Reports. The key point of stakeholder engagement is dialogue with stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting should not be viewed as a one-point-in-time activity but instead an ongoing process. Figure 1. is drawn from extant literature, the most recent sustainability reporting frameworks, i.e., AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard (AA1000 SES) (AA1000, 2015), and Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Reporting Standards (GRI Standards) (GRI, 2016), as well as being informed by neo-institutional theory. This conceptualisation gives rise to

Figure 1. Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting Towards More Meaningful Sustainability Reports

Source: Adapted from AA1000 (2015); Barone et al. (2013); Bellucci et al. (2019); Bradford et al. (2017); Greco et al. (2015); GRI (2016);

Herremans et al. (2016); Kaur & Lodhia (2018); Manetti & Bellucci (2016); Romero et al. (2019)

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 2022 | 7

Ardiana

Conceptualising Stakeholder Engagement In Sustainability Reporting several avenues for future empirical research on stakeholder engagement by utilising the proposed model in Figure 1., as outlined in the following sub-sections.

Result and Discussion

Planning, Implementing and Controlling Stages of Stakeholder Engagement. In the planning stage, reporting companies should define who their stakeholders are and decide the basis used to identify and classify them. Freeman (2010)describes stakeholders as an individual or groups of individuals having legitimate claims on, or interest in, the organisation’s operations which can affect or be affected by the organisations’ activities. Stakeholders can be categorised into primary stakeholders (those without whose continuing participation, the company cannot survive as a going concern) and secondary stakeholders (those who are not engaged in transactions with the organisation and are not essential for its survival) (Clarkson, 1995). Meanwhile, A. T. Lawrence & Weber (2014) categorise stakeholders as internal-market stakeholders (e.g., employees and managers), external-market stakeholders (e.g., stockholders and

creditors), and external-nonmarket stakeholders (e.g., the government and

(Mitchell et al., 1997) suggest three important stakeholder attributes which would be forming stakeholder salience (i.e., the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims), namely power, legitimacy, and urgency. The more

|

Basis of Identification and Classification |

Description |

Table 1. Examples of Basis of Stakeholder Identification and Classification

|

Dependency |

Those who either directly or indirectly rely on the company’s activities, products, and performance, or on whom the company relies to operate |

|

Responsibility |

Those to whom the company currently has responsibility, or may have responsibility in the future – legally, commercially, ethically, or morally |

|

Tension |

Those who urgently need attention from the company on financial, social, or environmental issues |

|

Influence |

Those who can have an effect on the strategic or operational decision making of the company or stakeholders |

|

Diverse perspectives |

Those whose different perspectives may facilitate new understanding about the existing conditions and may help identify chances for alternative actions that may not otherwise be taken |

|

Power |

Those who have the ability to use resources to make an event happen or to secure a desired outcome |

|

Legitimacy |

Those who have a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, definitions |

|

Urgency |

Those who call for immediate attention on claims |

Source: Adapted from AA1000 (2015), A. T. Lawrence & Weber (2014), Mitchel et al. (1997).

attributes the stakeholder has, the more salience it is for the organisation. Definitive stakeholders (i.e., those which have power, legitimacy, and urgency at the same time) may come from any stakeholder which initially had only one or two attributes but it eventually has three attributes by forming coallition with other stakeholders. Meanwhile, AA1000 (2015) suggests that the reporting company may use one or combination of basis of stakeholder identification and classification, namely dependency, responsibility, tension, influence, and diverse perspectives. Table 1. shows alternative bases of stakeholder identification and classification.

After defining stakeholders, and deciding the basis of stakeholder identification and classification, the reporting company shall consider all potential risks of stakeholder engagement between the company and stakeholders (Andriof et al., 2017). Table 2. shows several potential risks of stakeholder engagement.

Table 2. Potential Risks of Stakeholder Engagement

Risks from the Perspective of Risks from the Perspective of Reporting

Stakeholders Companies

Relevant stakeholders may show The company’s reputation may be reluctance to engage with the company harmed by stakeholder engagement for certain personal reasons because its activities and performance

are closely under scrutiny by stakeholders

Relevant stakeholders may perceive stakeholder engagement as an energy and time-consuming activity

Relevant stakeholders may set a certain level of expectation from their engagement, but the company may fail to meet the expectation

Power among relevant stakeholders is not balanced which may result in unbalanced influence from strong and weak stakeholders on company’s policy Relevant stakeholders may show disruptive actions during the engagement Relevant stakeholders may be uninformed about the scope of engagement or disempowered in the process of engagement

Technical difficulties may happen especially when stakeholder engagement involves technological devices

Invited relevant stakeholders may show conflicting interests and views during the engagement

The company may perceive stakeholder engagement as a money and timeconsuming activity

The company may experience loss of control of issues

Expectations of stakeholders may not be fully met by the company

Stakeholders may express strong criticism of the company

Stakeholder engagement may create conflict of interests between the company and stakeholders, or among stakeholders

Internal disagreement in the company may happen in following up the engagement

Criticism, comments, and suggestions from stakeholders may be in conflict with regulations or internal policies in the company

Source: Adapted from AA1000 (2015), Andriof et al. (2017).

Having considered the potential risks of stakeholder engagement, reporting companies should decide on an approach to engagement for each identified stakeholder

group (Rinaldi et al., 2014). Gao & Zhang (2006) posit that stakeholder engagement can be in the form of passive engagement (i.e., literally, the reporting companies do nothing), announcing engagement (i.e., this may include one-way communication from company to stakeholders via reports, websites, bulletins, letters, public presentations, among others, with a purpose to advocate company’s concerns to stakeholders or to inform them), listening engagement (i.e., the companies aim to monitor perception of stakeholders by asking them to provide comments and suggestions about companies’ sustainability issues), limited two-way communication engagement (i.e., the company communicates with stakeholders to consult or negotiate regarding a company’s sustainability issues, e.g., through focus group discussions, public meetings and workshops, bargaining with employees in unions, etc.), and active engagement (i.e., stakeholders are actively involved and empowered in an extensive two-way communication with the company, e.g., through partnerships, multi-stakeholder initiatives, and integration of stakeholders in the company’s governance, strategy, and operations).

Stakeholder engagement requires the support of multiple resources, such as financial, technological, and human resources. In many cases, the capacity of the resources needs to be developed and increased as a preparation for engagement with stakeholders (AA1000, 2015). For example, communication and negotiation skills may need to be improved before the engagement with employees, media, and other stakeholder groups. Companies may need technological devices to communicate with relevant stakeholders in different geographical areas and they may need to prepare a budget for the engagement. As a part of the planning stage, companies also need to prepare all documents to record the process of stakeholder engagement, such as minutes of meetings, memorandums of understanding, and questionnaires. These documents are very important as a basis for accountability on stakeholder engagement (Rinaldi et al., 2014).

After being planned, it is the time for the implementation of the stakeholder engagement. The identified stakeholder groups should be invited to participate in an engagement as planned (Bellucci et al., 2019). The company should document the whole process as evidence and the basis of accountability. Stakeholder engagement does not end when companies received comments, suggestions, or critics from stakeholders (Unerman, 2007). It should develop an action plan and communicate the progress with stakeholders (AA1000, 2015). Later, the output of stakeholder engagement, together with the agreed action plan, will be continuously reviewed in the controlling stage.

As mentioned earlier, planned actions which were developed in the implementation stage should be followed up by responding to inputs (critics, comments, suggestions) from stakeholders for organisational improvement (Bellucci et al., 2019). The company should continuously monitor and evaluate current engagement for better planning and implementation in future engagements (Kaur & Lodhia, 2018). Last but not the least, the controlling stage is disclosing stakeholder engagement through one or more mediums for reporting, such as through stand-alone sustainability report, corporate website, and many other possible mediums, as an accountability mechanism (Rinaldi et al., 2014).

The Quality of Stakeholder Engagement. Stakeholder engagement is considered high quality if there is a binding commitment between the reporting company and its stakeholders. The high quality of the engagement is also shown by an integration of

stakeholders in the company’s governance, strategy, and operations (Adams & Frost, 2008). The scope of engagement should be set clearly in the planning stage and implemented consistently with a focus on sustainability topics that are relevant to both

the company and stakeholders in order to avoid the out-of-context discussions during the engagement (AA1000, 2015). As the essence of this engagement is an ongoing process of communication with stakeholders, for it to be good quality, it should involve the agreed decision-making process and opportunities of two-way dialogue between the company and stakeholders (Bellucci et al., 2019). Stakeholder engagement should be conducted in a timely fashion for the relevance of information and should be communicated transparently so its outcome adds value to both the reporting company and stakeholders.

The completeness of overall disclosures in sustainability reports has been questioned by those interested in using them. Most of the reporting companies tend to disclose only positive and neutral issues and try to hide negative issues (Bellucci et al., 2018). Disclosures in sustainability reports are complete if there is a balance of information between positive and negative issues about the company’s sustainability performance (Rinaldi et al., 2014). In other words, complete disclosures require no omission of relevant information reflecting sustainability aspects that facilitate or influence stakeholders’ decisions. In addition, the scope of reporting (i.e., the range of economic, social, and environmental aspects) should reflect significantly all corresponding economic, social, and environmental impacts of company’s activities, strategy, and performance on stakeholders while at the same time the stakeholders are able to assess the company’s sustainability performance (AA1000, 2015). Complete disclosures also require clear boundaries between those material economic, social, and

Table 3. The Meaningfulness of Sustainability Reports to Reporting Companies and Stakeholders from High Quality Stakeholder Engagement Practices

Meaningful for Reporting Companies Meaningful for Stakeholders

Long-term investment on company’s economic, social, and environmental concerns with various stakeholders

Mutual understanding and trust building with various stakeholders on company’s economic, social, and environmental issues, initiative, performance, and agenda

Integration of company’s economic, social, and environmental issues, initiatives, performance, and agenda into company’s strategy, governance, and operations

Long-term partnership with mutual respect on economic, social, and environmental concerns which have long-term impact on stakeholders Recognition by the company of stakeholder groups’ existence leading to mutual understanding and trust about company’s economic, social, and environmental issues, initiative,

performance, and agenda

Instead of receiving symbolic sustainability information, stakeholders may continuously receive credible sustainability information over time because company’s sustainability issues, initiatives, performance, and agenda are integrated into company’s strategy, governance, and operations

Source: Adapted from Adams & Frost (2008)

environmental aspects, i.e., how sustainability aspects impact within and outside the company. Not only material sustainability aspects need to be disclosed in current reporting period, material future impacts also need to be disclosed in current reporting period if they are reasonably predictable and may become unescapable or unalterable (Bellucci et al., 2019). Therefore, a higher degree of the completeness of overall disclosures in sustainability reports is indicated by more balanced information between positive and negative issues, a wider scope, and boundaries between aspects, and the inclusion current and future impacts in current reporting period.

Institutional Work Towards More Meaningful Sustainability Reports. All companies certainly engage with their stakeholders in their day-to-day operations. They interact with, among others, their customers, suppliers, employees, creditors, shareholders in running their business as usual. However, companies need to communicate about their sustainability issues, initiatives, performance, and agenda with their stakeholders for the purpose of disclosing this information in their sustainability reports (AA1000, 2015; GRI, 2016; Rinaldi et al., 2014). Companies may decide to engage with their stakeholders in sustainability reporting through various means such as, among others, brochures, questionnaires, email correspondence, focus group discussions, project partnership (Gao & Zhang, 2006). Unfortunately, not all of these stakeholder engagement approaches may reflect and facilitate the conditions needed for more

meaningful sustainability reports as well as a means of accountability to wider stakeholders.

To achieve a high level of accountability to a broader range of stakeholders and more meaningful sustainability reports, management of the reporting companies should be aware of and committed to the importance of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting. Commitment and awareness will only develop when managers consider the whole process of sustainability reporting as an investment instead of a cost for company (Bellucci et al., 2018). Without such commitment, disclosures in sustainability reports are merely information in documents or on websites as a communication to stakeholders that is empty of genuine meaning hence the reporting company will not benefit optimally from the reporting and nor will the stakeholders.

Stakeholder engagement practices which lead to more meaningful sustainability reports are those which add value or deliver advantages to both the reporting companies and stakeholders. Those practices which meet the main traits of high-quality stakeholder engagement practices may result in more meaningful sustainability reports. Table 3 presents the meaningfulness of sustainability reports to both the reporting companies and stakeholders which arises from a high quality of stakeholder engagement practices.

High quality stakeholder engagement practices should not be about the company disseminating sustainability information to stakeholders, but they are about everyone participating in the co-creation of knowledge and problem solving (Rinaldi et al., 2014). This is what transformational learning from stakeholder engagement is all about and supposed to be. It is not about a transaction that happens during stakeholder engagement (e.g., stakeholders ask for information and clarification about a company’s sustainability issues while the company responds to those stakeholders’ enquiries), but it is about changing a way both parties look at the world.

Diverse stakeholder engagement practices in sustainability reporting are present on a continuum of two ends created by theoretical perspectives (Rinaldi et al., 2014). In

Table 4. Main Traits of Stakeholder Engagement Perspectives

|

Strategic Management Tools |

Accountability Mechanism |

|

Stakeholder engagement is viewed as a |

Stakeholder engagement is an |

|

desire to manage expectations and |

accountability mechanism through a |

|

balance competing interests among |

variety of dialogic forms with wider |

|

stakeholders |

stakeholders It views stakeholders as both preparers |

|

It tends to view stakeholders only as |

and users of sustainability reports (i.e., |

|

users of sustainability reports |

managers and stakeholders participated in discussion about material topics to be disclosed in sustainability reports) It is considered as a pre-requisite and |

|

It leaves a lot of scope for the exercise |

primary means for developing |

|

of managerial discretion |

meaningful sustainability reporting structures (contents of sustainability report) |

|

Stakeholder engagement functions as a |

Stakeholder engagement is an |

|

public relations exercise with |

accountability mechanism for |

|

stakeholders. It may involve a dialogic |

sustainability concerns through a |

|

process to consult about stakeholders’ |

dialogic process with stakeholders and |

|

expectations but eventually the |

shared discretionary decisions between |

|

managers decide the contents of |

managers and stakeholders on the |

|

sustainability report |

contents of the sustainability report |

|

Source: Adapted from Rinaldi (2013); |

Unerman & Bennett (2004)

other words, there are two kinds of institutional logic in stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting through the neo-institutional theory lens, namely strategic management logic and also accountability logic. Table 4 distinguishes these two logics or perspectives.

Managers in reporting companies should act as institutional entrepreneurs who are able to challenge the existing practice of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting, envision, and make convincing the new and better practice towards more meaningful reports for the company and stakeholders (Hardy & Maguire, 2013). Institutional entrepreneurship is a notion in neo-institutional theory that reintroduces the interrelationship between agency, interests, and power into institutional analyses of organisations. By definition from Maguire et al. (2004), institutional entrepreneurship is “activities of actors who have an interest in particular institutional arrangements and who leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ones”. Earlier, DiMaggio (1988) argued similarly that “new institutions arise when organized actors with sufficient resources see in them an opportunity to realize interests that they value highly”.

Institutional actors who have the willingness to shift the practice of stakeholder engagement from a company’s strategic management tool to an accountability for wider stakeholders will have an institutional task to undertake in terms of disrupting the existing practice with the new proposed practice of stakeholder engagement (T. B. Lawrence et al., 2009). For example, institutional actors in the company may wish to promote a new approach of stakeholder engagement through a corporate web forum

which allows wider stakeholders to participate in a co-creation of knowledge and problem solving on company’s economic, social, and environmental concerns by disrupting the existing approach which does not allow for dialogic engagement or to limit the level of stakeholder participation. In this case, management support and commitment for the new practice of stakeholder engagement is very necessary for the institutional work to be successful. However, in many cases, a new idea aimed at an ideal practice has barriers which come from those who are in comfort zone and/or those who are risk averse or have difficulty accepting unpopular ideas. Institutional work requires time, emotion, commitment, energy, and financial support; therefore, it is fruitful to study the story of actors willing to create, maintain, and/or disrupt institutions in their companies.

Conclusion

Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting is expected to contribute to more meaningful sustainability reports, not only for the reporting companies but also stakeholders. In practice, engagement with stakeholders is interpreted and practiced in various ways but usually lies on a continuum between two ends, i.e., stakeholder engagement as strategic management tools (strategic perspective) and accountability mechanism to wider stakeholders (holistic perspective). Institutional actors in the reporting companies should promote stakeholder engagement approaches which shift the practice from strategic to holistic engagement. The institutional work of actors in disrupting existing stakeholder engagement practices plus introducing new and more holistic engagement practices indeed requires skill, strategy, and passion. A shift in along the continuum of stakeholder engagement from a strategic to a holistic perspective may contribute to more meaningful sustainability reports for reporting companies and stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting should be viewed as an ongoing process involving planning, implementing, and controlling stage of dialogic engagement between a reporting company and its stakeholders about sustainability issues, initiatives, performance, and agenda. Stakeholder engagement is a venue for a co-creation of new knowledge and problem solving on sustainability which becomes a common interest for both the preparers and the users of sustainability reports. Stakeholder engagement will only result in more meaningful sustainability reports when it is based on a continuous clear-scope dialogic and agreed decision-making processes with stakeholders on recent material sustainability issues by which a reporting company along with its stakeholders should have strong commitment to integrate sustainability issues into company’s strategy, governance, and operation and disseminate the agreed sustainability topics into sustainability reports transparently.

This conceptual paper has to be seen in the light of some limitations. First, sustainability reporting is voluntary in most countries and sustainability reporting frameworks (e.g., GRI Standards, AA1000 SES) exert normative influences (what ought to be reported) rather than coercive forces (what must be reported, with sanctions for the non-compliance). Second, the neo-institutional theory assumes the non-conformity response to institutional influences/forces. The theory implies that the global conception of stakeholder engagement introduced by the sustainability reporting frameworks may be perceived differently when it is translated into local contexts. These limitations suggest that the conceptual framework in Figure 1. needs to be adapted into companies or countries’ local contexts, instead of adopting it.

This paper facilitates several avenues for future research in the field of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting by exploring the relationship between approaches to such engagement, the quality of stakeholder engagement, and the meaningfulness of sustainability reports for both the preparers and users through qualitative analysis. It is fruitful to undertake empirical research in the area of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting by utilising the proposed model in Figure 1. as a conceptual framework. Several possible research questions for a future agenda of research are outlined below, but not limited to: First, what are the meanings of stakeholder engagement perceived by the reporting companies and stakeholders? Second, how do the perceived meanings of stakeholder engagement change over time? Third, how do the perceived meanings of stakeholder engagement shape their practices? Fourth, how do the reporting companies manage tension arising from diverse and conflicting interests and expectations of stakeholders? Fifth, how do dialogic stakeholder engagement practices improve the development of knowledge and understanding between the reporting company and stakeholders about sustainability issues, initiatives, performance, and agenda? Sixth, how do the reporting companies utilise internet-based forums and/or social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, among others) to engage with their stakeholders? Seventh, how do the reporting companies respond to stakeholder criticism? Eight, how do the reporting companies deal with stakeholders which have lack of voice and are not heard? Ninth, how do managers of the reporting companies introduce new stakeholder engagement approaches which are believed to be better at capturing and responding to stakeholders’ interests and expectations? Tenth, how does the inclusion of stakeholder groups into a company’s formal organisational structure affect company’s sustainability initiative, performance, and agenda? Lastly, how do stakeholder engagement practices in developing countries differ from those of in Western world?

References

AA1000. (2015). AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard. In AccountAbility. AccountAbility.

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(5), 731–757. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570410567791

Adams, C. A., & Frost, G. R. (2008). Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Accounting Forum, 32(4), 288–302.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2008.05.002

Andriof, J., Waddock, S., Husted, B., & Rahman, S. S. (2017). Unfolding stakeholder thinking: Theory, responsibility and engagement. In Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking: Theory, Responsibility and Engagement (1st Editio). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351281881

Ardiana, P. A. (2019). Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting: Evidence of Reputation Risk Management in Large Australian Companies. Australian Accounting Review, 91(29), 726–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12293

Barone, E., Ranamagar, N., & Solomon, J. F. (2013). A Habermasian model of stakeholder (non)engagement and corporate (ir)responsibility reporting. Accounting Forum, 37(3), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2012.12.001

Bebbington, J., Brown, J., Frame, B., & Thomson, I. (2007). Theorizing engagement: The

potential of a critical dialogic approach. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability

Journal, 20(3), 356–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570710748544

Bellucci, M., Manetti, G., & Thorne, L. (2018). Stakeholder Engagement and Sustainability Reporting. In Stakeholder Engagement and Sustainability Reporting. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351243957

Bellucci, M., Simoni, L., Acuti, D., & Manetti, G. (2019). Stakeholder engagement and dialogic accounting: Empirical evidence in sustainability reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(5), 1467–1499.

https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-09-2017-3158

Boiral, O. (2013). Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(7), 1036–1071.

https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2012-00998

Bradford, M., Earp, J. B., Showalter, D. S., & Williams, P. F. (2017). Corporate sustainability reporting and stakeholder concerns: Is there a disconnect? Accounting Horizons, 31(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-51639

Child, J., Lu, Y., & Tsai, T. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship in building an environmental protection system for the people’s Republic of China. Organization Studies, 28(7), 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078112

Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9503271994

Curtis, S. K., & Mont, O. (2020). Sharing economy business models for sustainability.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 266(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121519

Déjean, F., Gond, J. P., & Leca, B. (2004). Measuring the unmeasured: An institutional entrepreneur strategy in an emerging industry. Human Relations, 57(6), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726704044954

DEMIL, B., & BENSÉDRINE, J. (2005). Processes of Legitimization and Pressure Toward Regulation : Corporate Conformity and Strategic Behavior. International Studies of Management & Organization, 35(2), 56–77.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2005.11043728

Dew, N. (2006). Institutional Entrepreneurship: A Coasian Perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 7(1), 13–22.

https://doi.org/10.5367/000000006775870442

Dillard, J., & Yuthas, K. (2013). Critical Dialogs, Agonistic Pluralism, and Accounting Information Systems. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 14(2), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2011.07.002

DiMaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment (pp. 3–21). Ballinger. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10030010621/#cit

Dunn, M. B., & Jones, C. (2010). Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education, 1967-2005.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 114–149.

https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114

Ferrero-Ferrero, I., Fernández-Izquierdo, M. Á., Muñoz-Torres, M. J., & Bellés-Colomer, L. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting in higher education: An analysis of key internal stakeholders’ expectations. International Journal of

Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(2), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-06-2016-0116

Fitriasari, D., & Kawahara, N. (2018). Japan investment and Indonesia sustainability reporting: an isomorphism perspective. Social Responsibility Journal, 14(4), 859– 874. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-04-2017-0062

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic planning: A stakeholder approach. In Cambridge University Press.

Gao, S. S., & Zhang, J. J. (2006). Stakeholder engagement, social auditing and corporate sustainability. Business Process Management Journal, 12(6), 722–740. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150610710891

Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078958

Geissdoerfer, M., Vladimirova, D., & Evans, S. (2018). Sustainable business model innovation: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 401–416.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.240

Greco, G., Sciulli, N., & D’Onza, G. (2015). The Influence of Stakeholder Engagement on Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Italian local councils. Public Management Review, 17(4), 465–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.798024

Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.20785498

Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing Change: The Role of Professional Associations in the Transformation of Institutionalized Fields.

Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069285

GRI. (2016). Sustainability Reporting Standards. The Netherlands: Global Reporting Initiative.

Guide, A. J. (2021). Academic Journal Guide 2021. In ABS Academic Journal.

https://charteredabs.org/academic-journal-guide-2021/

Hahn, R., & Lülfs, R. (2014). Legitimizing Negative Aspects in GRI-Oriented Sustainability Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1801-4

Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2013). Institutional Entrepreneurship. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (Vol. 2, pp. 198–217). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200387.n8

Herremans, I. M., Nazari, J. A., & Mahmoudian, F. (2016). Stakeholder Relationships, Engagement, and Sustainability Reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(3), 417– 435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2634-0

Hörisch, J., Schaltegger, S., & Windolph, S. E. (2015). Linking sustainability-related stakeholder feedback to corporate sustainability performance: an empirical analysis of stakeholder dialogues. International Journal of Business Environment, 7(2), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2015.069027

Kaur, A., & Lodhia, S. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(1), 338–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-12-2014-1901

Keusch, T., Bollen, L. H. H., & Hassink, H. F. D. (2012). Self-serving Bias in Annual Report Narratives: An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Economic Crises. European

Accounting Review, 21(3), 623–648.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2011.641729

KPGM. (2015). Currents of Change: The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting.

Lawrence, A. T., & Weber, J. (2014). Business and society: Stakeholders, ethics, public policy. Tata McGraw-Hill Education.

Lawrence, T. B. (2008). Power, institutions and organizations. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (1st ed., pp. 170–197). SAGE Publications.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273256699_Lawrence_T_B_2008_Pow er_institutions_and_organizations_In_R_Greenwood_C_Oliver_K_Sahlin_R_Sudda by_Eds_Sage_handbook_of_organizational_institutionalism_170-

Lawrence, T. B., Leca, B., & Zilber, T. B. (2013). Institutional Work: Current Research, New Directions and Overlooked Issues. Organization Studies, 34(8), 1023–1033. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613495305

Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and Institutional Work. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of Organization Studies (2nd ed., pp. 215–254). SAGE Publications.

Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2009). Introduction: theorizing and studying institutional work. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional Work (pp. 1–28). Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596605.001

Maguire, S., Hardy, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional Entrepreneurship in Emerging Fields: HIV/AIDS Treatment Advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159610

Manetti, G., & Bellucci, M. (2016). The use of social media for engaging stakeholders in sustainability reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(6), 985– 1011. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2014-1797

Marquis, C., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Vive La Résistance: Competing Logics and the Consolidation of U.S. Community Banking. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 799–820. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279172

Michelon, G., Pilonato, S., Ricceri, F., & Roberts, R. W. (2016). Behind camouflaging: traditional and innovative theoretical perspectives in social and environmental accounting research. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 7(1), 2–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-12-2015-0121

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of who and What Really Counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9711022105

Ocasio, W., Thornton, P. H., & Lounsbury, M. (2017). Advances to the Institutional Logics Perspective. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (2nd ed., pp. 509–531). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280669.n20

Oliver, C. (1991). STRATEGIC RESPONSES TO INSTITUTIONAL PROCESSES. Academy of

Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4279002

Paul, J., & Criado, A. R. (2020). The art of writing literature review: What do we know

and what do we need to know? International Business Review, 29(4), 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717

Rinaldi, L. (2013). Stakeholder Engagement. In C. Busco, M. L. Frigo, A. Riccaboni, & P. Quattrone (Eds.), Integrated Reporting (127th ed., pp. 95–109). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02168-3_6

Rinaldi, L., Unerman, J., & Tilt, C. (2014). The role of stakeholder engagement and dialogue within the sustainability accounting and reporting process. In J. Bebbington, J. Unerman, & B. O’Dwyer (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability: Second Edition (2nd ed., pp. 86–107). Routledge.

Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P. (2021). Corporate Communication and Integrated Reporting: The Materiality Determination Process and Stakeholder Engagement in Spain. In M. A. Camilleri (Ed.), Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age (pp. 175– 195). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-264-520211011

Romero, S., Ruiz, S., & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2019). Sustainability reporting and stakeholder engagement in Spain: Different instruments, different quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2251

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Smith, J., Haniffa, R., & Fairbrass, J. (2011). A Conceptual Framework for Investigating ‘Capture’ in Corporate Sustainability Reporting Assurance. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(3), 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0661-4

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in the Higher Education Publishing Industry, 1958– 1990. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801–843.

https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional Logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (1st ed., pp. 99–128). SAGE Publications Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200387.n4

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The Institutional Logics Perspective. Oxford University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199601936.001.0001

Unerman, J. (2007). Stakeholder Engagement and Dialogue. In J. Unerman, J. Bebbington, & B. O’Dwyer (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability (pp. 86–102). Routledge.

Unerman, J., & Bennett, M. (2004). Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(7), 685–707.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2003.10.009

Waterhouse, J. H., & Tiessen. (1995). A Contingency Framework for Management Accounting Systems Research, Accounting, Managerial Accounting– The Behavioural Foundation. GridInc.

Wooten, M., & Hoffman, A. J. (2013). Organizational fields: Past, present and future. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 131–147). Sage California.

Yusoff, R., Yusoff, H., Abd Rahman, S. A., & Darus, F. (2019). Investigating Sustainability

Reporting from the Lens of Stakeholder Pressures and Isomorphism. Journal of

Asia-Pacific Business, 20(4), 302–321.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2019.1684170

Appendix 1 Key Publications Being Reviewed

|

No |

Key Publications |

Key Findings |

|

1 |

Barone et al. (2013) |

The paper proposes a prescriptive conceptual model of stakeholder engagement where dialogue with stakeholders in the ideal speech situation can enhance stakeholder accountability. |

|

2 |

Bellucci et al. (2019) |

Sustainability reporting can be a framework for dialogic accounting if stakeholder engagement is effective (i.e., with a high degree of participation in a dialogue on sustainability issues between a reporting company and its stakeholders). |

|

3 |

Bradford et al. (2017) |

In the absence of stakeholder engagement, sustainability reporting is not able to meet stakeholder concerns. |

|

4 |

Greco et al. (2015) |

Italian local councils (LCs) could not exploit the benefits of sustainability reporting even though they attempted to engage with stakeholders due LCs’ poor service, unresponsiveness to customer concerns and corruption. |

|

5 |

Herremans et al. (2016) |

Sustainability reporting characteristics (directness of communications, clarity of stakeholder identity, deliberateness of collecting feedback, stakeholder inclusiveness, utilisation of engagement for learning) are affected by stakeholder engagement strategies (informing/transactional, responding/transitional, involving/transformational). Informing (transactional) stakeholder engagement is associated with low sustainability reporting characteristics. Responding (transitional) stakeholder engagement is associated with medium sustainability reporting characteristics. Involving (transformational) stakeholder engagement is associated with high sustainability reporting characteristics. |

|

6 |

Kaur & Lodhia (2018) |

Stakeholder engagement is critical in the whole process of sustainability reporting – planning, implementing and controlling |

|

7 |

Manetti & Bellucci (2016) |

A small number of companies being studied engage with their stakeholders by using social media in defining their sustainability report content. |

|

8 |

Romero et al. (2019) |

Sustainability reports have a higher quality of sustainability information than annual reports because the former was prepared by engaging with a broader range of stakeholder groups. |

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 2022 | 21

Discussion and feedback