Revealing Practices of Fishermen Profit Sharing: An Ethnomethodology Study

on

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis

Vol. 17 No. 1, January 2022

AFFILIATION:

1 ,2,3Faculty of Economics and Business, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia

*CORRESPONDENCE:

THIS ARTICLE IS AVAILABLE IN:

DOI:

10.24843/JIAB.20222.v17.i01.p09

CITATION:

Latuconsina, F. B.,

Triyuwono, I., Mulawarman,

A. D. (2022). Revealing Practices of Fishermen Profit Sharing: An

Ethnomethodology Study. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 17(1), 128-145.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received:

22 November 2021

Revised:

29 December 2021

Accepted:

5 January 2022

Revealing Practices of Fishermen Profit Sharing: An Ethnomethodology Study

Fitriah Bidari Latuconsina1*, Iwan Triyuwono2, Aji Dedi Mulawarman3

Abstract

This study aims to uncover the practice of profit sharing of fisherman in Yainuelo Village, Central Maluku Regency and the meaning behind the practice. This research uses a qualitative method with ethnomethodology approach. The instruments for the data collection are observation and interviews whereas the informants in this study are eight people who work on fishing boats. The obtained data then analyzed using indexicality and reflexivity analysis. The results showed that the Yainuelo fisherman practiced profit-sharing in seven stages namely, tahlilan (praying), cooperation agreement, fish catching, loading and unloading, selling, bage sala (profit sharing between the owner of the ship and the owner of the raft), and barekeng (profit sharing between the shipowner and the captain and crew). In practice, they not only share material (money) but also share prayers, share happiness, information to train skills that are interpreted as brotherhood, justice, honesty and a spirit of help.

Keywords: profit sharing, ethnomethodology, fishermen.

Introduction

The application of accounting practices depends on the social and cultural aspects in which the accounting is applied. Every different social and cultural environment has special characteristics in the application of accounting. This is because of the different information needed in each business activity. One of the local accounting practices is profit-sharing accounting. Profit sharing as a business management approach has been around for a long time (Scheltema, 1985). However, profit-sharing is not born from economic transactions in the banking world which are currently very trendy but have long been practiced in Islamic civilization even before Islamic civilization (Firdaweri, 2014; Nafik, 2009:108). The concept of profit and loss sharing makes Islam in a position that represents anti-usury (Mulawarman, 2013).

The concept of profit sharing is also developing in sharia accounting (Rahmawati & Yusuf, 2020) namely in mudharabah, musharaka, musaqah, mukhabarah, and muzara'ah contracts. Mudharabah and musyarakah are trade contracts, while muzara'ah, musaqah, and mukhabarah are agricultural contracts (Mulawarman, 2013). In a mudharabah contract, the owner of the capital (shohibul maal) entrusts his capital to the manager (mudharib) with the aim of making a profit (Firdaweri, 2014). The mudharabah-based business concept is one of the driving forces that is able to touch the bottom layers of the nation's economy. Profit sharing is

a social reality, so that profit sharing grows and develops in accordance with the social and cultural contexts (Fardani et al., 2019). This means that the values possessed by a society as guidelines for thinking, acting and behaving have a very important role in influencing the form of accounting (profit-sharing) it self. Profit sharing as part of accounting studies also reflects a cultural product of society that creates profit sharing with its own system (Hanif, 2014). As seen in Hanif (2015) study, which reconstructed the mato revenue-sharing financial accounting system derived from Minangkabau values. The financial accounting in ths practice is only limited in the context of a business based on the mato system which is only used in a few Padang food restaurants.

Profit sharing is one of the schemes in Islamic economics (Khasanah, 2013). Etymologically, the profit-sharing system is defined as the distribution of profits and losses in a business. Antonio (2001:90), explains that profit sharing is a fund management system in the Islamic economy, namely the sharing of business profit between the owner of the capital (shahibul maal) and the manager (mudharib). The distribution of business profits can be made based on revenue (revenue sharing) or based on the achievement of profits (profit sharing).

There are five types of sharia (Islamic rules) contracts that are profit-sharing, namely mudharabah, musyarakah, muzara'ah, musaqah, and mukhabarah. Mudharabah and musyarakah are trade contracts, while muzara'ah, musaqah, and mukhabarah are agricultural contracts (Mulawarman, 2013). However, in practice the most widely used contracts are mudharabah and musyarakah contracts, although each is very rarely performed when compared to other sharia contracts, especially the sale and purchase contract (murabahah).

Profit sharing has been practiced in Indonesian society for a long time (Scheltema, 1985). In fact, long before Islamic banking introduced profit sharing through its products, profit sharing practices in Indonesian society can be found in the fields of agriculture, trade, plantation and marine (Khasanah, 2013). On the basis of these considerations, this study intends to capture the profit sharing with the perspective of the locality of Yainuelo fishermen in Maluku and reveal the meaning behind the practice.

Other studies that investigate the practice of profit sharing while interpreting profit sharing are seen in the research of Khasanah et al., (2013) and Harkaneri (2013). Khasanah et al., (2013) revealed that rice farmers in Malang Raya practice PLS in three forms, namely paroan, pertelonan, and bawohan which are interpreted as equality, prosperity, cooperation, and ta'awun or help. Profit-sharing based on Islamic values (syara') was also found by (Harkaneri, 2013), namely the values abreviated in KESOJUKAN (justice, sociality, honesty, and security) practiced by rubber farmers in the Kampar community. This is in line with research conducted by Izzah, et al., (2018) that portrayed the profit-sharing of clove within the Bobaneigo community which was based on the values of honesty, fairness, and sincerity.

The study on fisheries in economic aspects, especially accounting, is still rarely in demand. Research on fisheries sharing is more viewed from its legal aspects and its impact on fishermen's welfare (Indahyani & Khairuddin, 2016; Matrutty, 2006; Qurrata, 2014), where their research results show that profit-sharing is carried out based on net income after deducting costs, costs incurred by ship owners which are carried out once a month. The share received by the crew is also considered not providing welfare for fishermen.

By using an ethnometodological approach, this study not only aims at capturing the practice of sharing the profits, but also reveals the meaning behind the practice.

Barekeng which is practiced by Yainuelo fishermen is carried out transparently between fishing boat owners (here in after referred to as bobo owners), raft owners, and fishermen so there is no recording of sales transactions or costs incurred. Instead, the recording was held for non-cash sales and reporting was done orally at the same time. The reasons behind the chosing of this site are because more than 80% of Yainuelo residents are fishermen. Secondly, Yainuelo has the most bobo of all the traditional villlages. Thirdly, Islam is the only religion practiced here making it relevan to the profit-sharing value being discussed. Lastly, the research site is easily accessed.

Generally, profit-sharing is understood as sharing money if you already get income from the business. Hence, profit sharing can be done if there is a " revenue" both based on gross revenue (revenue sharing) and based on net income (profit sharing). However, fishermen of Yainuelo shared the profit long before the revenue of their efforts were obtained, both material and non-material sharing. The profit sharing received in the form of fish and money, as well as the practice of sharing among fishermen which is carried out based on an agreement (through a deliberation process) is one of the characteristics of Yainuelo's fishermen's profit sharing which should be distinguished from other profit-sharing practices found in previous studies so that it can become a role model in efforts to increase fishermen's welfare.

Research Method

This study aims to reveal the Yainuelo fishermen's profit-sharing practice and the meaning behind this practice. Based on these objectives, researchers used an ethnometodological approach. Ethnometodology is used to investigate or reveal indexes and other practical actions as an organized settlement of practices carried out in daily life in an organized manner (Garfinkel, 1967:11).

The process of gathering data from informants is carried out using interview, observation, and documentation techniques. In-depth interviews are based on general questions that are detailed and developed later when conducting interviews or when conducting the next interview (Afrizal, 2016:21). In-depth and unstructured interview techniques on various occasions were also carried out by researchers. This process provides very useful information for understanding the meaning of any phenomena that occur or they face. Meanwhile, participating observation focuses on the practice together and the other core activities that accompany it. The objective of participating observation is that the data obtained will be more naturalistic and unbiased.

Table 1. Research Informant

|

No |

Informants |

Age |

Information |

|

1 |

Bapak Irwan |

58 |

Owner of Bobo (fishing boat) |

|

2 |

Ibu Ita |

54 |

Owner of Bobo |

|

3 |

Bapak Ahmad |

44 |

Owner of Rakit (fish farm), and secretary of |

|

Yainuelo village | |||

|

5 |

Bapak Yamin |

52 |

Tanase (fishing boat captain) |

|

6 |

Bapak Tahir |

48 |

Masnait (fishing boat worker) |

|

7 |

Bang Ardila |

25 |

Masniat |

|

8 |

Bapak Hasan |

38 |

Bagaris (non-permanent fishing boat worker) |

Source: Processed Data, 2021

Owner of Raft

Non-permanent fishing boat worker (Bagaris)

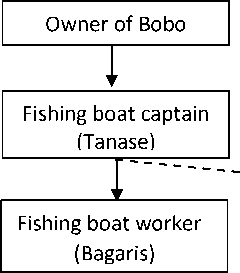

Keterangan :

◄----------► : Coordination line

---------* : Command line

-------► : indirect command line

Figure 1. The Relationship Between the Informants

Source: Processed Data, 2021

The data analysis techniques used in the study followed (Garfinkel, 1967), namely indexicality analysis, contextual action, and reflexivity analysis. Indexicality analysis is an analysis that focuses on expressions, behaviors, and is shown explicitly by actors in carrying out their work and arguments in completing their work (Rawls, 2008). Indexicality is obtained informants about how they practice sharing (barekeng). Reflexivity analysis is an analysis of the implied expressions of a situation and the expressions of actors as well as the meaning between phenomena/events. The reflexivity analysis reveals the things that are implied from each social interaction of informants practicing profit sharing.

This research was conducted on bobo net fishermen in Yainuelo village, located on Seram Island, central Maluku regency, Maluku Province. In this study, the researcher determined the informants purposively, by considering that the selected informants could provide more in-depth and reliable information to obtain valid data. The informants involved in this research are as follows, The relationship between the informants is depicted by the Figure 1.

Result and Discussion

Yainuelo village is a coastal village located in Central Maluku regency, Maluku Province. Its location is close to the beach, making the people in this village mostly works as fishermen. Since the last few years, local fishermen have started fishing in groups using fishing boats (hereinafter referred to as bobo) as their fishing fleet. This business requires cooperation between bobo owners, raft owners and fishermen. The owner of the bobo and the owner of the raft are the owners of the capital. The bobo owner of provides the bobo complate with all the equipment, while the raft owner provides the raft as a fish “field”. Meanwhile, the cooperation between the bobo owner and fishermen is similar to a mudharabah agreement where the bobo owner acts as shohibul maal (capitas owner) and fishermen as the mudharib (manager). Where, the owner of the capital entrusts his capital to the manager to earn profits (Firdaweri, 2014). The income earned is distributed using a profit-sharing system, which is Yainuelo people termed barekeng.

The practice of fishing using bobo nets always begins with tahlilan held by the bobo owner after the bobo is bought. This tahlilan ritual is performed as an expression of

Figure 2. Fishing boat (bobo)

Source: Processed Data, 2021

Figure 3. Raft

Source: Processed Data, 2021

gratitude for the purchase of bobo. This procession is usually followed by the stage of agreeing on a cooperation agreement (baku ator) between the bobo owner, the raft owner and the fishermen as well as a sign of the start of the fishing business. The whole results of the first catch will be donated as an expression of gratitude and hope that the business carried out can continue and as thanks to the prayers of many people who are considered to bring blessings. Not all of the catches are allocated for sale, some are given to the crew and also for charity (sadaka ikan). The proceeds from the sale of fish that will be shared come from selling fish to jibu-jibu (retail fish traders) and selling fish to fish freezing companies (cold storage). Profit sharing is carried out in two stages, namely profit sharing between the bobo owner and the raft owner, known as the bage sala. The two portions received by the owner of the bobo will then be shared with the permanent crew members who are termed together. However, in practice the portion received by the fishing crew is further divided by the non-permanent crew through a deliberation process which is termed a bage gandong (brotherhood). In addition, by using ethnometodological analysis, the researcher presents each stage of profit sharing and the meaning behind the practice. Below are the pictures of a bobo and a raft.

Starting a business with Tahlilan begins as the purpose of human being created by the Almighty God is in order to worship Him. Worship is not only in the sense of prayer, zakat, almsgiving and others but includes all aspects of human life, including working to meet the needs of life. Humans who have the belief in God's power as the highest absolute power will always depend all their efforts on Allah Ta'ala, the Almighty God, as long as it does not conflict with shari'ah (Islamic rules). Fishermen in carrying out their fishing business always depend on Allah SWT, the Almighty God to be blessed. Therefore, before starting his business, the owner of a bobo usually starts by holding tahlilan at his house as an expression of gratitude and hope that he will be given safety and blessings in his business. (Kamayanti & Ahmar, 2019) revealed that tahlilan or slametan (in Javanese culture) is done so that humans are given safety and are protected from all distress. According to Chodjim (Chodjim, 2011), humans who initiate their actions by praying to God will be of good value, because humans believe that there is no power and effort but those that are blessed by God.

Likewise, with the Yainuelo people, they believe that starting a business by holding tahlilan will be good for the business and for the surrounding community. This is as expressed by Pak Irwan in the following quote:

"Here, if someone has just bought a fishing boat, before catching fish, we carry out tahlilan first. At that time, my father who bought a bobo also helda tahlilan."

The same thing was also expressed by Mrs. Ita:

"Alhamdulillan (Thank god), given sustenance by Allah so that we can afford to buy bobo. That's why we make tahlilan.”

The two statements above show the indexicality of tahlilan, that is, they carry out prayer readings as an obligation before starting a fishing business that has become a habit of the local community. Tahlilan is held as a form of gratitude for the abundance of sustenance and to ask Allah for protection while running the business.

The meaning of reflexivity from the indexicality of the tahlilan above is that as a servant, humans always depend on Allah, the creator, to get blessings in business, be given protection, health, and sincerity at work. Recting prayers is also a form of society in being grateful for God's grace for the sustenance it receives. Asking Allah SWT that the fortune he receives will be able to bring many benefits to others. The following is a quote from Pak Irwan's statement:

"We carry out tahlilan first, so that the business runs smoothly, it can provide benefits to many people, not just for me and the workers in bobo."

Pak Irwan's statement above reflects that by praying, he hopes that the sustenance that is obtained through the business he runs is blessed sustenance, which benefits many people around him, not only to him and his workers. This is also in accordance with what Rasulullah, peace be upon him, said that "And the best people are those who are most beneficial to humans (Narrated by Thabrani and Daruquthi).

So, Tahlilan is a joint prayer reciting held at Mr. Irwan's house, which was attended by workers and other invitations who are understood as a form of gratitude, supplication and hope to Allah SWT to be given fortune and blessed effort and kept away from all calamities and dangers.

Gathering to agree on a cooperation agreement (baku ator) means the cooperation between bobo owners and fishermen resembles a mudharabah agreement, where the bobo owner acts as the owner of the capital (shohibul al maal) and the fisherman acts as the manager (mudharib). In this cooperation the terms and conditions must be fulfilled. There are four pillars of mudharabah contracts, namely contract actors (capital owners and managers), mudharabah objects (capital and work), consent (willingness), and profit ratios (Nurlinda, 2018).

After the implementation of tahlilan, Pak Irwan, Pak Yamin and other fishermen began to sit together in the living room. This meeting is a formality, because in fact the cooperation agreement has been conveyed by Pak Irwan since the purchase of bobo, when he started calling his relatives and neighbors to become crew in his bobo, at the same time he also immediately informed the part they would receive. This also applies when he offers the job to other people and also to those who come to his house to ask to be appointed as crew. Even though it is a formality, according to Pak Irwan this meeting is necessary and obligatory, because what was discussed during the recruitment of employees was still limited to the profit-sharing ratio, while other clearer rights and obligations had not been discussed.

Pak Irwan as the owner of bobo opened the meeting by reading Basmalah followed by greeting. Furthermore, he began with the appointment of a tanase, any duties and responsibilities, followed by the general duties of the masnait, while the technical duties of the masnait were completely left to the tanase, the leader of the fishing boat (bobo). This is as he expressed to researchers:

“When I recruited them first to become crew members, I told them what part they would receive. But other matters such as the rights and obligations of each party

should also be discussed. That's why, after the tahlilan we gathered to organize it. I called those who would be working in bobo to gather in the living room. After saying hello, I began to open the meeting. I appointed Pak Yamin as the captain of the ship (tanase), whatever his authority is, as well as the permanent crew (masnait). Regarding the masnait’s task in bobo, I leave it to Pak Yamin to arrange it. What are their rights, from the sharing of fish and food to sharing. We talked about everything that day, made it clear before they started work. "

Pak Irwan's statement above shows the indexicality of the baku ator, where the bobo owner and the fishermen gather to discuss the cooperation agreement carried out after the tahlilan takes place at the house of the bobo owner. The cooperation agreement must be clarified before starting a business (Nurlinda, 2018), as well as fishing businesses. Including the rights and obligations of bobo owners and crew, starting from the sharing of fish meals to the portion received by each party when sharing the results (together). This is as explained by (Nurhayati & Wasilah, 2013:56), a contract is an agreement between two or more parties that creates a legal obligation, namely the consequences of rights and obligations, which bind the parties directly or indirectly in the agreement.

Gathering and discussing the cooperation agreement together (baku ator) reflects that through this way, each party will be open to each other, they share any information so that everyone involved knows what their duties and responsibilities are, reinforcing rights and obligations of each party, what can and cannot be done. The main principle in the standard stage is that each party protects each other's rights, reminds each other in fulfilling their obligations and there is mutual respect and trust between the bobo owner and his employees. This is as explained by Pak Irwan:

“If it's fun to sit together, we can manage it well, right? Whatever my rights and obligations, theirs too. And if there are objections, they can also be discussed together. We have to clarify the contract, not to cause problems in the future."

The above statement "if sitting together is good, right" reflects that the agreement reached through deliberation is more giving peace to all parties. They share information, especially about the rights and obligations of each party. And if at the meeting, there are still things that might harm other parties, they can still be renegotiated. Cooperation agreements must be discussed in advance to avoid future disputes. (Khasanah, 2013) states that in the profit-sharing system (PLS), the principle of calculating profit-sharing and risk of loss must be determined from the beginning of the cooperation agreement so as not to be trapped in gharar practice.

The cooperation agreement between the bobo owner and the fisherman crew was carried out at the beginning of the recruitment of the crew members, then continued formally when the tahlilan ritual was finished which was carried out verbally and openly because it was based on trust and togetherness. The standard process is carried out at the beginning with a clear division of duties and obligations with the intention of avoiding disputes in the future, especially regarding the profit-sharing ratio received by each party.

Going to sea (Pi Buang Jaring) is an effort to get sustenance as going to sea has become a tradition because it has been strongly attached to and identifies the Yainuelo community, so that local fishermen seem to have used Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) on their fishing procedures. This is as stated by (Parera, 2012) that initially knowledge about how to go to sea and catch fish was obtained from the results of oral communication between parents and children, but often children are also involved to participate in catching / fishing so that inadvertently explanations from people parents

and the participation of children when they go to sea together are stored in their memory or brain, and this event is used as one of the tacit to tacit knowledge.

The fishing business using bobo also requires a raft as a "fish farm", where fish gather. There are two kinds of rafts used by fishermen, traditional rafts made of bamboo structures tied with ropes and to make them float in the middle of the sea, four large river stones are used which are tied to all four sides. Meanwhile, the modern raft is made of viber, rubber and a small house on it made of wood. In addition, they also need a boat to be used when the nets are thrown into the sea. The distribution of tasks to each community was carried out by tanase before departure to the raft (conditionally). Bobo and all his equipment are prepared in the afternoon. Starting with checking the engine, nets, and fuel in the form of diesel and premium, while ice cubes and supplies such as food and drink as well as cigarettes are brought when they leave. As said by Mr. Yamin below:

"Before leaving, we usually gather here [around the katapang (terminalia catappa tree) which is used as the Yainuelo fishing center], to prepare everything. This afternoon they had cleaned and tidied the nets and refueled, then heated the engine, so tonight we just need to bring ice blocks, supplies and raise the boat. They also bring a container to fill the fish to eat, both regular and non-permanent crew, all the same. "

Mr Yamin's words "before leaving, we usually gather here, preparing everything." shows that before going to sea, Mr. Yamin, masnait and bagaris (non permanent crew) must prepare everything in advance. They gathered on the beach around the ketapang tree. Mr. Yamin again confirmed their readiness before going to sea, starting from checking the nets, heating the engine, who were the masnaits and how many additional bagaris people participated in the sea that night. Furthermore, they raised ice blocks, landed boats and did not forget to also provide food, drink and cigarettes. After all the preparations have been completed, then under the command of Mr. Yamin, precisely at 11.00 evening began to move away from the shoreline towards the middle of the sea. While heading to the raft, the masnait shared a break. The masnaits who are on standby during the trip are those who are in charge of the machine section, they do it in turns, although it does not rule out the possibility of other masnaits also accompanying them while enjoying a cup of coffee, cigarettes and a modest provision. As expressed by Mr. Yamin when the researcher interviewed him before they went to sea.

“We went to sea to take our share. We are fishermen, our share is in the sea. If you don't leave, you get nothing. Even if you feel drowsy, when the time for departure arrives, you must leave. If the location of the raft is close, then around 02.00 in the morning we will just leave, but if the location is far away then we leave early at around 11 evenng, depending on the position of the raft, waiting for information from the owner of the raft."

Pak Yamin's statement "We go to sea to take our share" shows that to get their share of sustenance is by going to sea and picking up their sustenance. Going to sea is a way for fishermen to catch fish which is considered as a human obligation to fulfill their daily needs. Pak Yamin continued his statement "We are fishermen, our part is in the sea. If you don't go, you don't get anything” reflects that you have to pick up your sustenance. And one way to get sustenance is to work. As a fisherman, his main job is fishing.

After Bobo arrived on the raft that the tanase had indicated, the engine was turned off and a moment later the masnaits deftly carried out their respective duties. There was a task of tying the rope to the raft, preparing the ice, tying the rope to the bobo goalpost and the rest getting ready to throw the net around the raft. Then they waited until tanuar time arrived. The tanase command is the direct command used to lower the nets into the sea. This is as described by Mr. Yamin:

"When they arrived near the raft, the engine was turned off and they immediately lowered the terminal. Then they get ready in their respective positions, some tie the rope to the goalpost, insert some ice blocks into the hold, the fish viewing section will prepare the lights that will be used to see the fish "whether they have entered the raft or not", the masnait who others are waiting for my orders to cast the net. "

Mr Yamin's statement "they are getting ready in their respective positions, waiting for my order to throw the net" shows the indexicality of fishing, the way they catch fish using bobo nets. Once bobo arrived near the raft, they deftly assumed their respective roles, doing their best so that when the moment the fish entered and gathered around the raft, they were ready to execute. The command from Mr. Yamin as an instruction to throw the net reflects that cooperation and cohesiveness in the bobo netting business is an absolute for the achievement of common goals. Teamwork in groups leads to better efficiency and effectiveness. Group members will try to give their best contribution to both their energy and thoughts as a form of responsibility for achieving goals (Hatta et al., 2017).

The fish that have been netted are then put into palka (storage room). Fish that are still caught in between nets that are likely to be "deformed" if released are given as a "bonus" to anyone who releases them. Subsequently the intentions and bagaris, under the command of Tanase slowly began to leave the raft to return to the mainland. On the way home, Mr. Yamin then determined the amount of fish eaten by the fishermen based on the night's catch. As for sadaka fish, there is no special allocation because the distribution is based on the conditions when they pull over, how many children and people are considered unable to wait on the beach when they dock.

So, the process of going to sea begins from preparation to return to the mainland. When going to sea, the crew were led by a tanase who was fully responsible for the bobo, starting from directing the bobo to the raft that had been agreed upon beforehand, giving command when it arrived on the raft to the distribution of food fish received by all the crew members, whether still or not. This knowledge about fishing is obtained from generation to generation. The distribution of fish to eat is carried out by tanase before the bobo lands on the shore again.

Loading and unloading (Bongkar-Muat) is a means of sharing with others, the loading and unloading activity is one of the most enjoyable activities. Moment "romantic", a phrase that the researcher attaches to this activity. When bobo pulls over, it shows the excitement of the meeting between husband and wife, father and child, to the meeting between buyers and sellers which is full of family nuances. The activity of reducing their catch is also a means for them to share with others. They share sustenance, share information ranging from the selling price of fish in the market, community celebrations (such as tahlilan, marriage, work, to children's education), to business activities marked by the presence of a “sudden market” that provides coffee, tea and several types of food (yellow rice, pulut rice [sticky rice] topped with grated coconut and palm sugar, to snacks for children, because at certain times, the beach will be crowded with children to welcome

Bobo's arrival. It is called a sudden market because it appears “suddenly” during the loading and unloading process which lasts approximetally two to three hours. Mrs. Ita says:

"We sat waiting for Bobo's return while telling stories, asking each other the news, how was the development of children's education, and informing each other about the selling price of fish in the market."

When bobo pulls over, the first thing that is done is to lower the fish to eat and give fish alms to those who are entitled to receive those who are also present on the beach when the bobo is anchored. The fish was brought down last. This is to provide opportunities for the community to sell their fish first to the jibu-jibu and the residents of neighboring villages who come to buy fish. Jibu-jibu is group of people, mainly the wives of the fishermen, who sell the catch. As stated by Mr. Yamin, quoted by the following researchers:

"This is like when Bobo stopped by. The masnait lowered the fish to eat and also distributed the fish. The fish was sent down last. We give priority to the distribution of fish to the mothers and children who come to collect their rations. Yes, we share our sustenance (smiling and pointing to some mothers who are holding some fish, then turn to the children who are hanging on the edge of the bobo."

The statement above "they, masnait, bring down the fish to eat and also distribute the fish. Barekeng fish were delivered the last” showing the indexicality of loading and unloading, where the first thing to do is to unload the fish for food, the main part of which is the right of the fishermen. There is a mutual agreement that fish for consumption is the first and first right that must be received by fishermen, so that even when loading and unloading fish, eating fish is the first part that is sent to the land. This activity went hand in hand with the provision of sadaka fish, which were given to several residents who deliberately came to the fishing center to wait for Bobo's return. The attitude of Mr. Yamin, who smiled when expressing "We are sharing sustenance" reflects that the free fish sharing activity has become a mutually agreed upon habit. They share sustenance with others, especially those who are considered less well off. This is also agreed by Mr. Irwan, the owner of bobo:

"It has become our habit here when bobo goes back home, we are obliged to distribute fish, not to sell everything."

The expression "it is mandatory to distribute the fish, not to sell everything" reflects that sharing the catch has become an obligation, it is abstinence for local fishermen to sell all their catch. Mr. Irwan as the owner of the bobo feels he must give someone else's share of the proceeds that his bobo gets. He gave it to people who were considered less capable, they usually came to the fishing activity center before bobo anchored.

The loading and unloading activity is a very meaningful activity because it is a means of sharing with others. They not only share the catch known as sadaka fish (alms) but also share information with others, especially fellow family financial managers (mothers). Besides that, this activity is also a place for friendship with others.

Sales (Bajual) is not solely profit oriented, the sale stage is an important stage in together, because the sales proceeds are used to share results. The sales proceeds come from two sources, namely selling to fish freezing companies (hereinafter referred to as cold storage) and to jibu-jibu. Marine assets in the form of fish are assets with a short economic life, so determining the selling price needs to pay attention to several things,

such as the type of fish, the size of the fish, and the freshness of the fish. Apart from that, natural factors also influence the selling price of fish. The type of fish with the highest selling price is fish included in the export list, such as tuna and skipjack. Likewise with the size of the fish, the bigger the fish the higher the selling price and vice versa. The determination of the selling price of fish also takes into account the costs incurred by the bobo owner as the owner of the capital. However, there are differences in the treatment of the selling price to the clusting company and the jibu-jibu. When selling fish to Cold storage, larger companies, the selling price is higher because the bobo owner calculates all the costs already incurred (transfer cost). These costs include fuel costs, ice cubes, food and drink costs and transportation costs. While the selling price to jibu-jibu is lower, no profit target is expected from this sale, because it is based on the principle of mutual help and kinship, giving fishermen wives the opportunity to earn additional income, helping their husbands earn a living to meet their needs of family. This is as expressed by Mrs. Ita: “Mothers usually sell it to jibu-jibu and then bring it to the Cold storage”. In jibu-jibu the price is cheaper, they take it directly from bobo because they really need it more. We also don't really expect to profit from them. If you're lucky, thank God. They usually take the fish first, if it is sold, then the money will be paid. We are helping the brothers here so that they can earn extra income. If it is sold to Cold storage, the price is more expensive. They are big companies, aren’t they?”

The statement "Mothers usually sell to the jibu-jibu and brings it to Cold storage" shows the indexicality of sales. The fish they catch are sold to jibu-jibu and cold storage companies. Most of the fish sales to jibu-jibu are done on credit, based on trust and there is no target of how much profit to be made from this sale. Meanwhile, sales to fish freezing companies have a higher price. The results of sales from this party are expected to benefit more together. "If it is sold to the toilet, the price is more expensive. They are big companies, right? This reflects that Mrs. Ita expects profit from sales to the company not to the jibu-jibu, because the sale to jibu-jibu aims to help them improve the family economy.

Jibu-jibu is the first sales chain in practice of Barekeng. This profession is mostly practiced by housewives and among them is the backbone of the family, so putting jibu-jibu is a must. If the catch is low, the fish will be eliminated and only sold to jibu-jibu. As expressed by Pak Irwan:

“They, Jibu-jibu, are the backbone of the family, we have to sell to them first. If you get a little fish, we usually don't have Barekeng (distribution of rights between the crew), but try to keep the jibu-jibu available. I don't want to enjoy my own profit or just those who work in bobo. It would be better if the benefits could be enjoyed by many people, especially those in need. My wife and I really intend to help the people here with this bobo, although sometimes it doesn't give any profit, it's okay. The money can be found, sustenance can come from anywhere."

The statement above emphasizes the attitude of Pak Irwan and his friends to help the jibu-jibu, reflects that the sale of fish to jibu-jibu is prioritized before being brought to the cold storage. The insignificant profit that jibu-jibu gets is the basis for the attitude of Pak Irwan and his wife that the catch that is obtained is sold first to the jibu-jibu. This is done sincerely and leaves everything only to Allah SWT.

"They are participating so they can know the results of today's sales, as well as helping to lift fish for weighing." (Mrs. Ita)

When the fish are brought to the cold storage company for sale, the bobo owner is usually accompanied by several masnaits and bagaris. Their participation is so that all parties can know the results of the sale of that day. Mrs. Mrs Ita's statement "Here is today’s catch, so that later you know the results of today's sales to" reflects that the sale is carried out openly or transparently between the bobo owner and the crew members. There is no stipulation on who must join the chair and can be represented by anyone, which shows a very high attitude of mutual trust between them.

She did expect profit from sales but profit was not the main goal of the business he √started. Profits are not the ultimate goal, maximizing profit attainment actually makes humans become selfish and capitalistic being. Helping to alleviate other people's troubles is a real advantage.

Bage Sala is profit sharing between bobo owner and raft owner. The bage sala is the first stage for the Yainuelo fishermen's profit sharing, namely the sharing of the same capital owners. The relationship between the two parties can be described as symbiosismutualism. Symbiosis-mutualism is the right word that describes the relationship between the owner of the bobo and the owner of the raft. The bobo owner provides the bobo and all its equipment as a fishing fleet, while the raft owner provides the raft as a fish “field” which is then used to run a fishing business together. This cooperation is absolutely necessary because bobo only functions as a fishing fleet which requires a raft as a fish "field". As expressed by Pak Irwan:

"Fishing business using bobo nets, there must be a raft. Because the raft serves as a gathering place for fish, so bobo just comes, drops his net around the raft and then picks up the fish. So, there must be a raft. There are also those who call it sero but its function is the same for fish gathering places. What is certain is there must be a raft. "

The above statement states that “fishing business using bobo nets, there must be a raft. The raft serves as a place for fish to gather”, indicating that anyone who carries out a fishing business using bobo nets really needs a raft as a gathering place for fish to gather or as a fish “field”. The interdependence between the bobo nets and the raft is then applied by cooperation between the two with a sharing system. The profit sharing between the bobo owner and the raft owner is termed a bage-sala. The determination of the portion for the sharing of the results is agreed upon in a ratio of 2: 1, the owner of the bobo receives two parts and one part belongs to the owner of the raft.

Bage-sala is done every time bobo returns to sea. This is because the raft visited every time they go to sea can vary depending on the contract between the owner of the raft and the owner of the bobo or tanase before going to sea. The proceeds from sales to jibu-jibu and cold storage will then be reduced by operational costs. The costs incurred by the owner of the bobo every time he goes to sea include: fuel, ice cubes, eating, drinking, and cigarettes, including transportation costs when taken to the cold storage company. The bage-sala can be described as follows:

Assuming the catch as much as 2 tons at a price / kg of IDR 12,000

1 day's total sales : IDR 24,000,000

Operational costs : (IDR 5,000,000)

Transportation fee : (IDR 500,000)

The net income to be distributed is (2: 1) : IDR 18,000,000

What bobo owner received : IDR 12,000,000

What the raft owner received : IDR 6,000,000

The net income that will be shared above is shared between the owner of the bobo and the owner of the raft with a ratio of 2:1. The bobo owner receives two portions, namely IDR 12,000,000.00 in which there is a share of fishermen (masnait and tanase) while the raft owner receives one part of IDR 6,000,000.00. The part is masnait and tanase is kept by the owner of Bobo until they are together. So, if we examine this bage-sala is actually the same as a three-share, namely the net income is divided among three parties, namely the bobo owner, the raft owner and the fishermen. However, the share of masnait and tanase is temporarily detained by the owner of the bobo. Pak Ahmad on one occasion stated that:

"First, sharing between the bobo owner and the owner of the raft. They are divided by three, the owner of the bobo receives two parts while the owner of the raft receives one part. The two portions received by the owner of the bobo will later be divided again by masnait. We Yainuelo people usually call it bage sala (smiling). It's been like this for a long time, don't know who started the term (shrugging his shoulders, smiling). "

Based on Pak Ahmad's statement above, the indexical expression of "the term bage-sala" shows the difference in results received between the bobo owner and the raft owner, because the bobo owner receives two parts while the raft owner receives one part. When Pak Yamin expresses the term bage sala with a smile, it means reflexivity that bage sala does not actually mean a wrong and unfair division, because the two parts that are received by the owner of the bobo are part of the crew members. In addition, Mr. Ahmad's attitude, who shrugged his shoulders while smiling again at the end of the sentence, showed the meaning of reflexivity that he and the other raft owners took it for granted and did not object to the term, because a term did not necessarily show its true meaning.

The explanation above, gives an idea to us that the cooperation that exists between the bobo owner and the raft owner, is an absolute thing to do because there is mutual need between one party and another. The owner of the bobo needs the raft as a fish "field", on the other hand the owner of the raft needs the bobo as a fishing fleet. So, the relationship between the owner of the bobo and the owner of the raft can be described as "symbiotic mutualism". When viewed from a sharia “point of view”, it is similar to a musyarakah contract because both parties have capital and then partner in running a joint business. However, there are differences between these two agreements, which make them "similar but not the same". This difference mainly lies in the treatment when a loss occurs. In the musyarakah contract, if there is a loss in running the business, it will be divided proportionally according to the portion of the capital of each partner. Whereas in the bage-sala contract, the losses incurred are only borne by the owner of the bobo. For example, in one trip to the sea, the catch is small, so it is usually only allocated for ikang makang (not for sale), so the loss of fuel costs incurred by the owner of the bobo to go to the raft Mr. "x" is only borne by the owner of the bobo.

Barekeng is distributing tanase and masnait rights, in practice Yainuelo fishermen receive profit sharing in two forms, namely the sharing in the form of raw fish (ikang makang) and profit sharing in the form of money (barekeng). Profit sharing in the form of fish is given every time they go home from sea with the same portion of all parties involved in the collaboration, namely for tanase, masnait, bagaris, bobo owners and raft owners. Meanwhile, barekeng is done once a month or every two weeks if the catch is abundant. However, if there is a period of famine (transition and big waves), barekeng

can only be done after a period of two months. The money that is shared comes from the sale of the fish during several fishing trips after deducting all costs incurred by the owner of the bobo. The share of the profits between the owner of bobo and tanase and masnait is 60:40. Bobo owners receive 60% while tanase and masnait receive 40%. This is as expressed by Mr. Irwan:

“We usually do it together once a month. If there is a lot of fish in season, it can be done every two weeks. When it is the wave season, it can take up to two months to hold it together. "

Mrs. Ita further explained that:

"Our share is 60% while the share of the crew is 40%. later their share is divided equally among all. In addition, for Mr. Min, we will later take it from our share. Mr. Min is tanase isn’t he? so the share must be bigger than masnait. 60% includes the cost of maintenance of Bobo. We give their share too?, so that it can be used to pay the children's school fees, or for other purposes. "

The part of bobo received by Mrs. Ita is stored until it is time to share it with the fishermen (tanase and masnait). Mrs. Ita's statement "we give their share too?" ending with the word "to" reflects that she and her husband are obliged to fulfill the rights of the tanase and masnait who work for their bobo. The rights received by fishermen are in the form of money that can be used for larger purposes such as paying school fees for children or can be used for other purposes such as buying clothes and others.

The operating costs incurred by the bobo owner before working together do not include the cost of maintenance or maintenance of machines and other fishing equipment. The cost of maintenance / maintenance of a bobo machine can reach IDR 30,000,000, while the purchase price of a net is IDR 15,000,000. The amount of maintenance costs for machines and other fishing tools is more so that the share received by the bobo owner is greater, namely 60% of the total net of sales.

The time of Barekeng is the time that the Bobo crew has been waiting for, including Bagaris. When the information was shared by Pak Irwan and / or Mrs. Ati, they all rejoiced in welcoming the happy news. Tanase and several other people representing the masnait gathered at Pak Irwan's house after the evening prayer, around 20.30 WIT while the rest gathered at Mr. Yamin's house to take their share. The following is the expression of Mr Ardila and Mr Tahir:

"Alhamdulillah (Thank God), tonight is the time for profit sharing. I'm waiting for him, for the cost of giving birth to his wife later. " (Mr Ardila)

This was also confirmed by Mr. Tahir:

"Yes, Alhamdulillah. I want to buy my son's school shoes, he has repeatedly asked to buy them. " (Mr Tahir)

Mr Ardila and Mr. Tahir's statement "Alhamdulillah" while wiping a hand on their chest shows the moment they have been waiting for because they will receive payment that is their right. When hearing the news together, a smile flashed on the faces of Mr. Tahir and his friends while mentioning what to do with the money together, reflecting that barekeng is very helpful for them in fulfilling their bigger needs, which require large amounts of money, there are hope pinned on together.

Barekeng is sometimes held for two weeks if the catch is abundant or if there is an urgent need from one of the bobo fishermen. It could be based on requests from fishermen who ask for their rights for urgency, but it could also be due to policies from Mr. Irwan and

Mrs. Ita. As the researcher witnessed that day, Mr. Irwan delivered the following sentence:

"I heard from Mrs. Ita, “Mr Ardila said that his wife was about to give birth. So last night I asked Mrs. Ita to tell you that today we are sharing the profits. Alhamdulillah, yesterday, you caught a lot of fish, so that's enough for the profit sharing. You don't mind right?”

Mr. Irwan took the policy of doing together two weeks earlier because he considered the needs of one of the people who were considered urgent. The question "you don't mind right?" at the end of his statement reflects that every decision taken must have the approval of all parties involved in the cooperation. Even though it is the right of the masnait, he still asks for the willingness of the others. This is intended to prevent misunderstandings between them because it is related to meeting the different needs of each bobo fisherman.

In addition to working together between the bobo owner and the crew members, Yainuelo fishermen also practice sharing among crew, namely sharing the results between tanase, masnait and bagaris. This profit-sharing was initiated by the tanase and is a uniqueness of the joint which is not found in other regions. This profit-sharing is taken from the manager's share of 40% by going through a deliberation process first and is based on bagaris performance. The following is Mr. Yamin's statement to the researcher:

"Actually, this profit-sharing is between us (permanent employees) and the owner of the bobo only. But after time passed, we also shared with the temporary crew. Because they are also very diligent. It seems unfair if we share the results only among ourselves. You took it from us after going through deliberation with masnait"

Pak Yamin's expression "It seems unfair if we share the results only among ourselves" means that he wants to give a sense of justice to all the crew members whose performance is considered good. This is because they share the same risk while in the sea.

Even though it is seen from a capitalist point of view, the profit sharing between these fishermen is crucial to them (tanase and masnait), but because it is based on the strong bond of brotherhood (gandong) among fishermen and as basudara (family) in their village they sincerely share and continue to practice it until now. The following is statement from Pak Yamin:

"Well ... we consider this Bage Gandong, sharing with fellow brothers and sisters, fellow fishermen who both depend on their lives from fishing. Even though the amount they received is not the same as ours, they are happy because at least they have also been appreciated."

"Alhamdulillah, we also include sharing time with us. Let it be a little, but we understand this, because they really have the obligation. Although only as freelancers, Pak Yamin and friends already appreciate our work." Mr. Hasan said

Well, they call it bage gandong, sharing with fellow brothers and sisters as a form of brotherhood. The share received by permanent employees (tanase and masnait) is not the same as that received by temporary crew members (bagaris) because of the inherent responsibility of permanent employees who act as managers. The risks arising from their mistakes are certainly their responsibility, which does not apply to bagaris who only have status as freelance employees. But for bagaris, they feel very benefited by this profitsharing because it gives them the same opportunity to earn income. In addition, they also

have a greater opportunity to learn and work at bobo when a person decides to quit due to illness or other reasons.

So, a bakereng is the net sales proceeds obtained from the total sales minus the operational costs [costs] carried out at a predetermined time. Barekeng reflects on the distribution of fishermen's rights entrusted through the bobo owner. Mr. Irwan and Mrs. Ita carried out their obligations by conveying a mandate to those who had the right to receive it which was carried out openly and full of family nuances. Together with fellow fishermen who voluntarily set aside their share (tanase and masnait) for bagaris through a meaningful process they sincerely share in order to provide justice and can strengthen brotherhood.

In addition, there is an interesting meaning in this plot where the existence of bagaris is actually very important for tanase and masnait because their portion will be reduced by the division. However, because of the strong sense of brotherhood (gandong) between them as village brothers and sisters, it has become something common and has become a mutually agreed upon provision. Mr. Yamin also tries to appreciate by giving fairness to those who are serious in their work even though they are a freelance employee, because fairness does not lie in the same amount of money received but puts something in its portion.

Conclusion

This study uses an ethnometodological approach to reveal the way of Yainuelo fishermen practicing together and the meaning behind the practice The results of this study indicate that there are seven stages in the process barekeng, namely biking tahlil, baku ator, casting net, loading-unloading, bajual, bage sala, and barekeng. In practice, they not only share material (i.e money), but they also share prayers, share blessings, share happiness, share information, and share knowledge (skills). That is, they share the results both in the economic, religious and social aspects. Barekeng with fellow fishermen is also done sincerely to provide fairness to each other. Barekeng also showed sincereity and social concern of the bobo and crew owners to share with each other. In other words, barekeng gives more benefit to all parties, including the people and nature around them.

Limitations encountered in this research process, among others, were that some of the data obtained by the researcher was still not optimal, because without the direct involvement of the researcher in these stages, such as in tahlilan, the baku ator that had been held long before this research was carried out. Furthermore, the stages of fishing are carried out only by men and carried out from night to morning, making researchers unable to be directly involved in it. For further research, it should be carried out from the beginning of the fishing boat purchase (bobo) so that all stages of sharing the results can be followed in order to obtain more optimal data in relation to the meaning making of barekeng.

References

Afrizal. (2016). Metode Penelitian Kualitatif: Sebuah Upaya Mendukung Penggunaan Penelitian Kualitatif dalam berbagai Disiplin Ilmu. Raja Grafindo Persada.

Antonio, M. S. (2001). Bank Syariah dari Teori Ke Praktik. Gema Insani Press.

Chodjim, A. (2011). Al-Fatihah: Membuka mata batin dengan surah pembuka. Serambi Ilmu Semesta.

Fardani, N., Nafi’ah, A., Kurniawan, S. C., & Putra, G. S. (2019). Penerapan bagi hasil

antara sopir bus dengan toko oleh-oleh malang. Oetoesan-Hindia: Telaah Pemikiran Kebangsaan, 1(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.34199/oh.1.2.2019.004

Firdaweri. (2014). Perikatan Syari’ah Berbasis Mudharabah (Teori dan Praktik). ASAS, 6(2), 54–77.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Study Ethnometodology. Prentice Hall.

Hanif. (2014). Memaknai Bagi Hasil Sistem Mato (Studi Etnografi di Group Restoran Padang X Jakarta. Universitas Brawijaya Malang.

Hanif. (2015). Introducing Mato Based Profit-Sharing Accounting and its Synergy with Cooperative and Sharia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 211(November 2015), 1223–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.163

Harkaneri. (2013). Memahami Praktik Bagi Hasil Kabun Karet Masyarakat Kampar Riau (Sebuah Pendekatan Etnografi). Universitas Brawijaya Malang.

Hatta, M., Musnadi, S., & Mardani. (2017). Pengaruh Gaya Kepemimpinan, Kerjasama Tim, dan Kompensasi Terhadap Kepuasan Kerja Serta Dampaknya pada Kinerja Karyawan PT PLN (Persero) Wilayah Aceh. Magister Manajemen Fakultas Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Unsyiah, 1(1), 70–80.

Indahyani, F., & Khairuddin. (2016). Sistem Bagi Hasil Nelayan Pukat Cincin di Kota Parepare. Jurnal Galung Tropika, 5(2), 63–70.

Izzah, D. (2018). Kearifan Lokal pada Sistem Bagi Hasil Petani Cengkeh di Bobaneigo Halmahera Utara Maluku Utara (Issue September). Universitas Brawijaya Malang.

Kamayanti, A., & Ahmar, N. (2019). Tracing Accounting in Javanese Tradition. International Journal of Religious and Cultural Studies, 1(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.34199/ijracs.2019.4.003

Khasanah, U. (2013). Analisis Praktik-praktik Sistem Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS) Pada Masyarakat Petani Padi di Malang Raya. Universitas Brawijaya.

Khasanah, U., Salim, U., Triyuwono, I., & Gugus Iriyanto. (2013). The Practice of Profit and Loss Sharing System For Rice Farmers in East Java, Indonesia. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 9(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.9790/487x-0930107

Matrutty. (2006). Alternatif Pola Bagi Hasil Nelayan Purse Seine (Studi Kasus Di Kecamatan Saparua). Ichthyos, 5(2), 51–56.

Mulawarman, A. D. (2013). Masa Depan Ekonomi Islam: Dari Paradigma Menuju Metodologi. IMANENSI: Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen Dan Akuntansi Islam, 1(1), 1– 74. https://doi.org/10.34202/imanensi.1.1.2013.1-13

Nafik, M. (2009). Bursa Efek dan Investasi Syariah. PT Serambi Ilmu Salemba.

Nurhayati, S., & Wasilah. (2013). Akuntansi Syariah di Indonesia. Salemba Empat.

Nurlinda, Z. (2018). Perspektif Mudharabah Pada Perbankan Syariah dan Sistem Bunga Pada Perbankan Konvensional. Polimedia, 22(2), 1–16.

Parera, J. M. (2012). Modal Sosial Sebagai Input Dalam Proses Aglomerasi dan Implikasinya Terhadap Biaya Transaksi (Studi pada UKM Perikanan dan Batu Bata). Universitas Brawijaya.

Qurrata, V. A. (2014). Perbandingan Sistem Bagi Hasil Tiga Alat Tangkap dan Implikasinya pada Kesejahteraan Nelayan Desa Sendang Biru Kabupaten Malang. Jurnal Ilmu Perikanan Tropis, 19(2), 85–92.

Rahmawati, & Yusuf, M. (2020). Budaya Sipallambi’ Dalam Praktik Bagi Hasil. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 11(2), 386–401.

https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jamal.2020.11.2.23

Rawls. (2008). Ethnomethodology’s Program: Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism.

Littlefield Publishers.

Scheltema, A. M. P. . (1985). Bagi Hasil di Hindia Belanda (Marwan (ed.)). Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 2022 | 145

Discussion and feedback