EXPLORING STRIP INTERCROPPING POTENTIALS OF MAIZE-PULSE CROPS TO FIGHT CLIMATE VARIABILITY IMPACTS IN DRYLAND AREAS

on

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BIOSCIENCES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY • Vol. 5 No. 1 • September 2017 ISSN: 2303-3371

https://doi.org/10.24843/IJBB.2017.v05.i01.p01

ARTICLE

EXPLORING STRIP INTERCROPPING POTENTIALS OF MAIZEPULSE CROPS TO FIGHT CLIMATE VARIABILITY IMPACTS IN DRYLAND AREAS

I Komang Damar Jaya*, Sudirman, and Rosmilawati

Faculty of Agriculture University of Mataram *Corresponding author: ikdjaya@unram.ac.id

ABSTRACT

Recent climate variability affects maize production in dryland areas. This study aimed to explore potentials of strip intercropping of maize-pulse crops in improving productivity of dryland areas. The study was conducted in dryland area of Gumantar village, North Lombok (8.253654 S, 116.285695 E). Soil in that area was categorized as poor soil with the following properties: 0.46% organic matter, 0.05% N total (Kejdhal), available P 11.25 ppm (Olsen) and exchangeable K 0.77 me%, pH 7.0 and field capacity 29% (%/V). Rainfall data were collected during the growing seasons of 2016/2016 and 2016/2017. A field experiment of maize-pulse crops strip intercropping was conducted during a dry season of 2016. The component crops in the strip intercropping were maize NK212, maize NK7328, mungbean Vima-1 and groundnut Hypoma-1. All component crops were grown as monocropping and strip intercropping of maize-pulse crops in 8.4 x 5.0m plot size for each treatment. To measure productivity of the strip intercropping, relative yield total (RYT) and benefit to cost ratio (B/C) were calculated. They were great variations in rainfall in the last two years. From the experiment, data showed that all the strip intercropping treatments have RYT and B/C values >1 meaning that strip intercropping of maizepulse crops is more productive than monocropping and is feasible to be practiced in dryland areas. With the short growing period and their drought tolerant nature of the pulse crops, especially mungbean, the strip intercropping can be used to fight climate variability impacts in dryland areas.

Keywords: drought tolerant, feasible, monocropping, productivity, rainfall

INTRODUCTION

Dryland contribution in fulfilling food needs of the world population is large enough. Approximately 14% of the total world population rely on dryland areas to support their livelihoods (Nicholson, 2011).

The same author further attributed that the portion of dryland areas is

approximately one third of the total area of the Earth's surface. More recent data show that the total dryland areas on globe was 6.09 billion hectares. In these dryland areas live about 2.1 billion people that are largely poor (van Ginkel et al., 2013). These facts demonstrate the important of dryland in

meeting the needs of food of the world population continues to grow.

One of the most common food crops grown by dryland farmers is maize. This plant is much grown because of it high economic value and high productivity. Lately it has been a lot of modern maize hybrid varieties for sale on the market and very accessible to farmers. But as maize plants in general, hybrid maize plants are also very sensitive to drought stress, especially at the time of flowering and grains filling stages (Qakir, 2004). Maize plants which failed to get sufficient water at flowering stage or at cob filling stage can loss yield significantly. For maize plants grown in dryland areas, the main source of irrigation water during the rainy season relies heavily on rainfall. Other crops that also frequently grown by dryland farmers are pulse crops, such as mungbean and ground nut.

The climate change phenomenon that we have experienced lately affects rainfall pattern. Rainfall in Nusa Tenggara Barat

Province of Indonesia is predicted to vary and this will affect crops production, especially in dryland areas. In general, it was predicted that there will be less rainfall during rainy season (Kirono et al., 2016). In dryland areas where the soil texture is dominated by clay, the decrease amount of rainfall during the rainy season may have a slight impact on crops, particularly maize crops since the soil is able to store the water well. On the other hand, when the dryland soil texture is dominated by sand, reduced rainfall or the occurrence of dry spells may cause significant reduction in maize production. The above facts show that maize farmers in dryland are deeply affected by the climate change phenomenon, particularly with rainfall variability. As it is often reported, dryland farmers are mostly poor farmers who do not have sufficient capital and technology to be able to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Studies on improving dryland farmers resilient to the effects of climate change are needed. More importantly, a

simple crop growing technology that is adaptive to the recent climate variability is needed since most of dryland farmers are conventional farmers.

The simple practice of cultivating crops on a dryland that was reported can be used as one of the strategies to face the climate change effects in dryland areas is intercropping (Liu et al., 2016).

Intercropping is one form of crop diversification that meant to spread the risk failure of crops on a piece of land. There are many models of intercropping and one of them that has been reported to have many advantages is strip intercropping (Li et al., 2001). Strip intercropping is growing two or more crops in narrow strips on a stretch of land. In this study, the potentials of strip intercropping on a dryland were explored and the productivity advantage of the strip intercropping over monoculture was calculated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study area was a dryland in Gumantar Village, Lombok Utara District, Nusa Tenggara Barat Province. Climate type in the study area according to Oldeman classification is D type. The soil type is Entisol with loam structure and was categorized as poor soil with 0.46% organic matter, 0.05% N total (Kejdhal), available P 11.25 ppm (Olsen) and exchangeable K 0.77 me%, pH 7.0 and field capacity 29% (%/V). To get rainfalls data, a rain gauge was installed at the experimental site (8.253654 S, 116.285695 E) and the rainfall was collected and measured every day during the rainy seasons of 2015/2016 and 2016/2017. Maize yield data from the farmers’ land in Gumantar Village during the two years period was gathered by interviewing 10 farmers.

A strip intercropping field experiment was conducted during a dry season of 2016. During the experimental period, a deep-well pump was operated as the source of irrigation water. The irrigation was done by flooding

the plots approximately for 15 minutes for every irrigation time and the irrigation was given once a week until two weeks before maize harvest.

The treatments were: (A) NK212 (Syngenta) maize monoculture; (B) NK7328 (Syngenta) maize monoculture; (C) Groundnut (var. Hypoma-1) monoculture; (D) Mungbean (var. Vima-1) monoculture; (E) Strip Intercropping maize NK212-groundnut; (F) Strip intercropping maize NK212-mungbean; (G) Strip intercropping maize NK7328-groundnut; and (H) Strip intercropping maize NK7328-mungbean. The size of each treatment plot was 8.4 x 5m with east-west orientation. Maize crops were planted as double-rows with 35 x 20cm spacing within the row and 70cm between the double rows with one seed per hole. Groundnut and mungbean (pulse crops) were planted at 20 x 20cm with one seed per hole. From these spacings, there were 8 pairs of double-row maize in monoculture and 6 pairs of double-row in strip intercropping, while for pulse crops, there

were 44 and 10 rows for monoculture and strip intercropping, respectively. In terms of land use, the maize crops in the strip intercropping treatments occupied 70% and the pulse crops occupied 30% of the total land in each plot.Maize crop was fertilized three times, namely at planting, at 35 days after planting (DAP) and 56 DAP. At time of planting, Phonska N-P-K (15-15-15) fertilizer was applied at a rate of 300 kg ha-1 along with Urea fertilizer at a rate of 100 kg ha-1. At 35 DAP, Phonska was reapplied at the same rate as at planting time. Then Urea fertilizer only was reapplied at 56 DAP at a rate of 200 kg/ha. For pulse crops, Urea fertilizer at a rate of 50 kg/ha and Phonska fertilizer at a rate of 125 kg/ha were given at planting and at 35 DAP. Before the application of the second fertilizers, hand weeding was done in all the experimental plots. No pest problem was observed during the experiment.

The variables measured in this experiment were maize dry grains yield, mungbean dry seeds yield and ground nut

dry seeds yield per plot treatment. This yield per plot treatment then was converted into yield per hectare to calculate Relative Yield Total (RYT). RYT is one of the methods to measure production gain by intercropping method over monocropping by summing relative yield of each component crop. Relative yield (RY) of component crop is the yield of that crop species in intercropping relative to its yield in monoculture (Spitters, 1983). The equation to calculate RYT proposed by Spitters (1983) is RYT= RY1 + RY2, where the subscripts denoting the crop species. The economic efficiency of all the cultural practices tested in this study was determined by benefit to cost ratio (B/C ratio).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

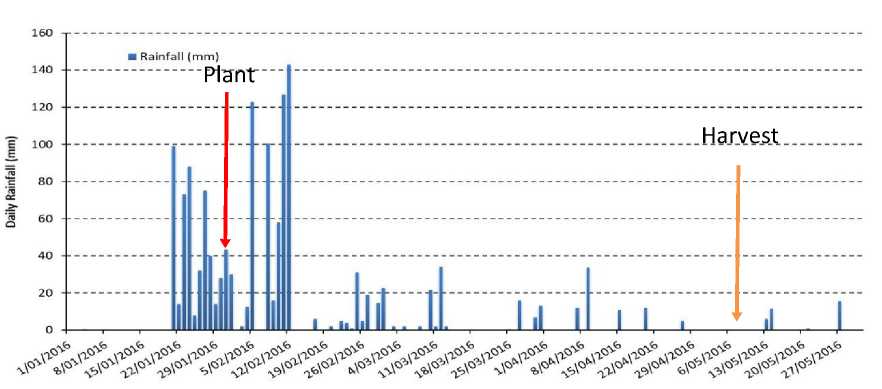

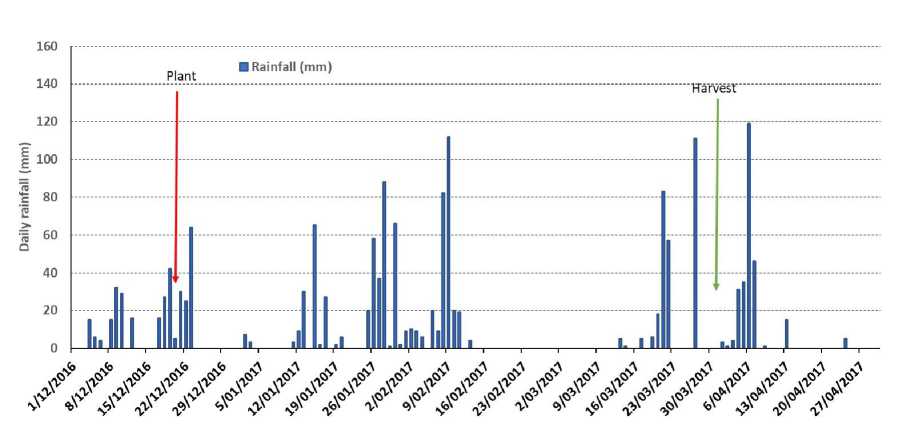

There were great variations in rainfall pattern during the rainy seasons of 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 (Fig. 1 and 2). The rain was started much earlier in the rainy season of 2016/2017 than in the rainy season of 2015/2016. In the earlier growing

season, the interviewed farmers planted their crops on 5 January 2016 and the harvest date was on 10 May 2016. In the growing season of 2016/2017, the farmers planted their maize on 20 December 2016 and the harvest time was on 4 April 2017. Total rainfall received by crops grown by farmers in the growing season of 2015/2016 was 7% higher than those crops grown in the growing season of 2016/2017 (Table 1). Crops grown during the previous growing season received 47% more rainfall than those the later growing season during the early growth stage up to anthesis. Dry spells occurred in the later growing season for about 3 weeks when the crops were at anthesis stage. During the grain filling up to harvest period, however, maize crops grown in 2016/2017 received rainfall more than four times higher than those grown in 2015/2016. Data gathered from the maize farmers around Gumantar showed that they got approximately 40% less yield in the later year of the growing season.

All crop species grown in strip intercropping were more productive than when there were grown in monoculture. These shown by the values of RYT of the strip intercropping that all were >1.0 (Table 2). The relative yield (RY) values of the two maize varieties were all >70%, in mungbean both were >30% and in groundnut the RY values were ≤30%.Earlier it was explained that 30% of the maize crop species was replaced by either mungbean or groundnut in the strip intercropping treatments to form 70:30

composition of maize and pulse crop, respectively.

In term of benefits to costs ratio (B/C), all the strip intercropping cultural practices had values of larger than 1.0 (Table 2). Growing maize crops in strip intercropping, either with mungbean or groundnut produced higher values of B/C as compared to growing them in monoculture, especially the NK212 maize variety that had the lowest B/C value. In this experiment, the highest B/C value was achieved when the groundnut Hypoma-1 variety planted in monoculture.

Fig. 1. Rainfall distribution during the maize growing season of 2015/2016 in Gumantar Village, North Lombok. Red arrow shows the planting time and green arrow shows the harvest time

There were great variabilities in rainfall pattern during the growing season of 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 in dryland areas of Gumantar Village, North Lombok (Fig.s 1 and 2). These variabilities were predicted to happen in Indonesia because of the recent climate change that will affect rice and other food crops production (Naylor et al., 2007). The effect of less rainfall received by crops grown in 2016/2017 as compared to those crops grown in the previous year was a 40% yield reduction. The most contributing factors to this yield reduction were the less water available during the early growth period up to anthesis (Table 1) as well as dry spells that occurs at around anthesis time (Fig. 2). This statement agrees with the earlier results by Ҫakir (2004). The large amount of rainfall received during the grain filling up to harvest period in the later growing season (Table 1) might cause some difficulties for maize farmers to do postharvest handlings.

Considering those variability in the rainfall patterns and problems that possibly faced by the maize farmers in dryland areas, simple cropping strategies need to be developed. One of the cropping strategies to adapt to climate change is growing more crop species (crop diversification) on a piece of land (Liu et al., 2016). Strip intercropping is one kind of crop diversification to improve the land productivity. Results from strip intercropping experiment with 70:30 composition of maize and pulse crops showed that strip intercropping had an advantage over a monoculture. The RY values of the two maize varieties (NK212 and NK7328) grown with mungbean and groundnut were always larger than 70%. These data show that the two maize varieties were more productive when they were grown in strip intercropping than in monoculture. Moreover, the RYT values of the strip intercropping that all greater than 1.0, further show the advantage of the strip intercropping over the monocultures.

The highest RYT value was observed in maize NK212-mungbean strip intercropping (Table 2). In this treatment, the strip intercropping benefitted yield 31% more than monocropping. Mungbean is a short duration crop that can be fitted well in dryland cropping systems, especially as an adaptation strategy to climate change. This crop is a drought resistance crop, especially after reaching 8 weeks of age (Ranawake et al., 2012). When the rain variability is high or when dry spells occur, as in Fig. 2, mungbean can secure its yield and this means that the risk of the main crop (in this case

maize), can be spread into other crops, such as mungbean. In Table 2 also can be seen that NK212 performed better than NK7328 in strip intercropping with pulse crops.

Strip intercropping has a great prospect and feasible to be developed as one of adaptation strategies to climate change in dryland areas. This feasibility can be seen from Table 2 where all B/C values of the strip intercropping models are larger than 1.0. These results indicate that the net present value of benefits doing strip intercropping is greater than net present value of the costs.

Fig. 2. Rainfall distribution during the maize growing season of 2016/2017 in Gumantar Village, North Lombok. Red arrow shows the planting time and green arrow shows the harvest time

Strip intercropping maize with groundnut benefitted more than strip intercropping maize with mungbean. This was due to the high market value of the groundnut as can be seen from the very

high B/C ratio value of the groundnut when it was grown in monoculture (Table 2). The only problem is that the growing period of the groundnut is much longer than mungbean.

Table 1. Amount of rainfall received by maize crops in the two growing seasons in Gumantar Village, North Lombok

|

Growing |

Rainfall received (mm) |

|

season |

Early growth Anthesis Grain filling to Total (18 DAP) (65 DAP) harvest |

|

2015/2016 2016/2017 |

812 1056 74 1130 134 850 325 1051 |

Table 2. Relative yield (RY) of the component crops, relative yield total (RYT) of the strip intercropping, and benefits to costs ratio (B/C) of all the cultural techniques tested

|

Treatments |

RY Maize |

RY Mungbean |

RY Groundnut |

RYT |

B/C |

|

NK212-Mungbean |

0.92 |

0.39 |

- |

1.31 |

1.64 |

|

NK212-Groundnut |

0.92 |

- |

0.28 |

1.20 |

2.94 |

|

NK7328-Mungbean |

0.78 |

0.34 |

- |

1.10 |

2.02 |

|

NK7328-Groundnut |

0.80 |

- |

0.30 |

1.10 |

3.26 |

|

NK212 Monoculture |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.38 |

|

NK7328 Monoculture |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.84 |

|

Mungbean Monoculture |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.05 |

|

Groundnut Monoculture |

- |

- |

- |

- |

11.6 |

CONCLUSIONS

There was a great variation in rainfall patterns due to climate variability in the last two years in dryland areas of Gumantar

Village, North Lombok. These variations had resulted in a lower maize crop production and it is believed that this variation will continue to do so. A simple cropping

strategy, such as strip intercropping of maize and pulse crops (mungbean and groundnut) has been proven to improve the dryland productivity. This type of intercropping can be developed as an adaptation strategy to the climate variability in dryland areas because the crop failure risk due to rainfall variability is spread into many crops. Strip intercropping of maize-groundnut produces higher economic benefits than maizemungbean but the latter is more resilient to the recent climate variability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was part of Applied Research and Innovation Systems in Agriculture (ARISA) Dual Cropping Project at University of Mataram funded by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) Australia contracted to Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO).

REFERENCES

Ҫakir, R. (2004). Effect of water stress at different development stages on

vegetative and reproductive growth of corn. Field Crops Research, 89 : 1-16. Kirono, D. G. C., Butler, J. L., McGregor, A., Ripaldi, J., Katzkey., & K.

Nguyen. (2016). Historical and future seasonal rainfall variability in Nusa Tenggara Barat Province, Indonesia: Implications for the agriculture and water sectors. Climate Risk Management, 12 :45-58.

Li, L., Sun, J., Zhang, F., Li, X., Yang, S., & Rengel, Z. (2001). Wheat/maize or wheat/soybean strip intercropping I. Yield advantage and interspecific interactions on nutrients. Field Crops Research, 71:123-137.

Liu, S., Connor, J., Butler, J. R. A., Jaya, I.

K .D., & Nikmatullah, A. (2016). Evaluating economic costs and benefits of climate resilient livelihood strategies. Climate Risk Management, 12 : 115-129.

Naylor, R. L., Battisti, D.S., Vimont, D.J., Falcon, W.P., & Burke, M.B. (2007). Assessing risks of climate variability and climate change for Indonesia rice agriculture. PNAS 104 : 7752-7757.

Nicholson, S. E. (2011). Dryland Climatology. The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 SRU, United Kingdom: Cambridge University

Press.

Ranawake, A. L., Dahanayaka, N.,

Amarasingha, U. G. S., Rodrigo, W. D. R. J., & Rodrigo, U. T. D. (2012). Effect of water stress on growth and yield of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.). Tropical Agriculture Research & Extension, 14: 76-79.

Spitters, C. J. T. (1983). An alternative approach to the analysis of mixed cropping experiment. 1. Estimation of competition effects. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science 31: 111.

Van Ginkel, M., Sayer, J., Sinclair, F., Aw-Hassan, A., Bossio, D., Craufurd, P., El Mourid, M., Haddad, N.,

Hoisington,D., Johnston, N., Velarde,

C.L., Mares, V., A. Mude, Nefzaoui, A., Noble,A., Rao, K.P., Serray, R., Tarawali,S., Voduhe, R., & Ortiz. (2013). An integrated agro-ecosystem and livelihood systems approach for the poor vulnerable in dry areas. Food Security, 5: 751-767.

ASIA OCEANIA BIOSCIENCE AND BIOTECHNOLOGY • 11

Discussion and feedback