Lesson Learned: Shaping Collaboration Among Tourism Stakeholders During Mount Agung Eruption

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.9. No.1. (2022): 113-125

Lesson Learned: Shaping Collaboration Among Tourism Stakeholders During Mount Agung Eruption

Gde Indra Bhaskara*

Faculty of Tourism, Udayana University

*Corresponding Author: gbhaskara@unud.ac.id

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24922/eot.v9i1.85470

Article Info

Submitted:

February 10th 2022

Accepted:

March 15th 2022

Published:

March 31st 2022

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the situation during the eruption of Mount Agung and the roles played by tourism stakeholders during the crisis. The findings of the study provide a more in-depth understanding of the lessons acquired by tourism stakeholders in Bali when dealing with catastrophic events, particularly natural disasters. For the purpose of this study, this research included interviews with 19 informants from a variety of tourist stakeholders, as well as those in charge of coping with natural catastrophes. According to the findings of the research, there are several lessons that can be learned from the eruption of Mount Agung, which will help tourism stakeholders be better prepared in dealing with all of the crises that may arise in the future.

Keywords: natural disaster; tourism; volcanic; mount agung; stakeholder; crisis management.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Indonesia is greatly exposed to natural disasters by being located in one of the world’s most vigorous disaster hot spots, where numerous types of disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, floods, landslides, droughts and forest fires often occur. The average annual cost of natural disasters, over the last 10 years (2000-2010), is approximately at 0.3 percent of Indonesian GDP, while the economic effect of such disasters is mostly much greater at local or regional levels (Skoufias et al. 2017). There were two recent disasters occurred in Indonesia, Bali’s Mount Agung eruption in November 2017 and Lombok Earthquake in August 2018.

Indonesia is a country that prone to natural disasters. Bali and Lombok as part of Indonesia is also highly vulnerable to these natural events. This becomes more complicated because Bali and Lombok are a famous tourist destination and it means that special handling and guarantees are needed for tourists during their vacation in Bali and Lombok where natural disasters and crises can be minimized. The Bali’s Mount Agung volcano eruption has affected a number of international tourists visiting Bali Island. In November 2017, when the eruption occurred, number of international tourist arrival in Bali were 361.006, compared to 413.232 in November 2016 and 407 213 in November 2018 (BPS 2019). Nevertheless, the solid evidence that this natural disaster has affected tourism

industry is the amount of tourist visiting Bali in December 2017.

There is a steady number of international visitors to Bali in December from the year of 2012-2016 which account 9 percent of total visitors in each year, however, there is anomaly found in December 2017 where the number of visitors declining into 5 percent of total number of tourists in 2017 (BPS 2019). It is not surprising since many potential tourists cancelling their trips and diverted their vacation to neigbouring countries or similar tourist destination. Meanwhile, Indonesian Minister of tourism stated that Lombok is losing 100,000 tourists in 2018 because of a series of earthquakes that hit the resort island (Edoardo 2018).

The natural event such as Mount Agung great volcanic eruption is a proof that, a natural disaster causing a chaos to tourism industry. Tourists were stranded and misguided in Ngurah Rai Airport and Gili Trawangan island while Tourism providers in Bali were overwhelmed by the closure of the Ngurah Rai Airport. This research is going to offer a solution through an approach in using integrated and holistic disaster management framework related to tourism.

Natural Disasters in Indonesia

According to the Indonesian National Disaster Management Authority (BNPB) there were more than 19,000 natural disasters in the period 1815 - 2018 (BNPB, 2019), making Indonesia a useful country for any natural disaster analysis.

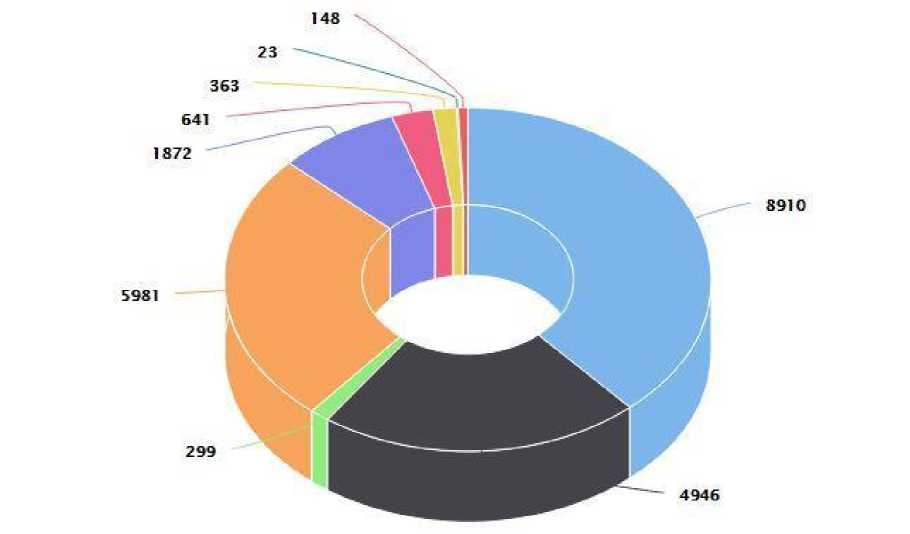

Figure 1. Number and types of natural disaster in Indonesia from 1815-2018 (Source: BNPB, 2019)

tsunamis and volcanic eruptions. Tsunami casualties recorded 174071 died, followed by volcanic eruption 78641. Tsunamis in Indonesia only occurred 23 times in the period 1815-2018 but caused the most fatalities. Meanwhile, earthquake is the main 114 e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Floods, landslides and tornadoes are the three most frequent natural disasters in Indonesia, with amount of 8910, 5981, 4946 events respectively. Although these types of natural disasters are the most frequent, however the most fatalities are http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

of pre-disaster phase, emergency phase and post-disaster phase. Prepared Phase, in the pre-disaster stage, BNPB carried out four main activities, namely prevention, mitigation, preparedness, early warning and community empowerment. Stage of Emergency is a series of activities carried out immediately at the time of the disaster to deal with the adverse effects, which include rescue and evacuation of victims, property, fulfilment of basic needs, protection, handling refugees, rescue and restoring facilities and infrastructure.

Emergency response is a stage of emergency status that starts from emergency alert, emergency response, and emergency transition to recovery. PostDisaster Phase, Availability BNPB Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Toolkit which has a post-disaster rehabilitation and reconstruction implementation tool, namely General Guidelines for Post-Disaster Rehabilitation and Reconstruction, Technical Guidelines for Budget Implementation for Post-Disaster Regional Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Activities, Guidelines for Settlement Sector Rehabilitation and Reconstruction, Implementation Guidelines Monitoring and Evaluation.

Tourism and Natural Disaster

For several years, the tourism industry has been affected by disasters such as the 1980 eruption of Mount Helens in the United States (Murphy and Bayley 1989), the 1991 Typhoon Val in Western Samoa (Fairbairn 1997), the 1995 eruption of the Soufrie`re Hills volcano in Montserrat (Kokelaar 2002), 1998 Australia Day

Flood in Katherine (Faulkner and Vikulov 2001), the 1999 Taiwan Earthquake (Huang and Min 2002), the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in East Japan (Nguyen et al. 2017) and recently The Eruption of Mount Agung in Bali (Bhaskara 2018) and Lombok Earthquake in Indonesia (Gayle and Bannock 2018, Schneider 2018). The disruptive 115 e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

cause for severely damaged houses and the second cause is flood. The most prone province for natural disasters in Indonesia is Central Java account for 5575 events and the least prone is North Borneo. From 1815 to 2018, the highest number of natural disasters occurred in Indonesia is in the year 2017. In Bali and Lombok, 2013 is the highest occurrence of natural disaster for the last decade (2008-2018) (BNPB 2019).

Natural Disaster Management Framework in Indonesia

The Indonesian government has issued a number of legitimate documents regarding Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR). The most significant one is Law Number 24 Year 2007 on Disaster Management (GoI 2007 in Djalante and Thomalla 2012). This law acknowledges the need to intensify hazard awareness and to improve a more organized and cohesive method to DRR. It introduces fundamental paradigm shifts on DRR from reactive to proactive approaches, formally acknowledges that DRR is an important part of the people’s basic right to protection and needs to be mainstreamed within government administration and development (UNDP Indonesia, 2008a, b).

The basic principles addressed in this legislation include public participation, public- private partnership, international collaboration, a multi-hazards approach, continuous monitoring, national and local dimensions, financial and industrial dimensions, an incentive system, and education (ADPC, 2008; UNDP Indonesia, 2008a, b). Key guiding documents for DRR in Indonesia include the first National Action Plan for Disaster Risk Reduction published in 2006 (BNPB, 2006). This was followed by the National Guidelines for Disaster Management 2010-2014 and the National Action Plan. Nowadays, when natural disaster occurred, BNPB is responsible for facilitating and helping the affected area through three stages, consisted http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

nature, inevitability and unpredictable occurrence of disasters has manifold implications for the tourism industry.

Firstly, disasters destroy the tourism infrastructure at destination, thus making them unable to receive tourists in the immediate aftermath. For example, the eruption in 1995 on Soufrie`re Hills volcano destroyed the capital, Plymouth, airports and seaports (Kokelaar, 2002). Almost all tourism infrastructure in Montserrat was paralyzed and access to the site was devastated. Secondly, disasters impact transit routes and source markets, by changing perception of destinations as being safe. For example, the impact of the Taiwan earthquake resulted in the number of international tourists visiting the island falling 15% (Huang and Min, 2002) after the eruption of Mt. Helens in the United States, the tourism industry in that area affected by the eruption, experienced a 30% decline in revenues (Murphy and Bayley 1989). Typhoon Val in 1991, consequently, tourist arrivals in Western Samoa fell sharply (Fairbairn, 1997).

Secondly, media play an essential role in intensifying this impact on tourist perception (Handmer and Dovers 2007), thus creating a ‘ripple effect’ (Ritchie 2004), which spreads the detrimental effects of disasters geographically and across economic sectors. Importantly, in the context of tourism, the ‘ripple effect’ hinders destination recovery as negative public perception of a disaster-affected destination hampers injection of foreign exchange, thus increasing the amount of time needed for the destination to be restored (Ritchie 2004).

Natural Disaster Framework for Tourism

The effects disasters can have on a destination, many tourism businesses and governmental organisations fail to develop Disaster Management strategies as part of

their business plans, since in some cases they consider the duty is not their own (Drabek 2000; Ritchie 2009). Hence highlighting the necessity for a formal response by destinations to develop Disaster management plans is indispensable (Prideaux 2004). The disaster management plans were normally created as a framework to manage the crisis and disaster, not merely for natural disaster incidents, however in order to fit in this study, these frameworks are used and applied to accommodate solely for natural disasters. Developed from approaches in Fink’s and Robert’s emergency management framework, Faulkner (2001) created a framework, namely Tourism Disaster Management Framework (TDMF).

This disaster management framework covers and outlines the lifecycle of a disaster from pre-event to resolution and assigned approaches and strategies to each phase of the event. It can be applied in a variety of tourism related disasters. His work later adapted by Prideaux (2004) in order to accommodate massive scale disasters and capable to address single or multiple disasters/crises. Nevertheless, the precursor; reconstruction and reassessment review and risk assessment component of the framework is modified by Prideaux (2004). The modification suggested to take further action to the original framework.

Study by Ritchie 2004 creates an approach called Crisis and Disaster Management Framework (CDMF) which based on the work of Faulkner 2001 and the strategic management literature. His work focused is on the development of strategy for monitoring and handling crisis or disasters in the tourism industry. Stressed on some stages prevention and planning, implementation and evaluation and feedback as attributes for strategic management of crisis or disasters Ritchie’s framework later adapted Novelli et al. (2018) – adapted in order to suit for developing countries which include Involvement of public e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

sector/ multiple stakeholders in prevention and planning, Inclusion of emergency fund to be administered by the Ministry of Tourism. Another disaster management framework is developed by Hystad and Keller 2008. They named their approach as Destination Disaster Management Framework (DDMF). This was created based on two case studies by the authors targeting tourism business in order to understand level of preparedness. Four stages are delineated from this framework such as 1) pre-disas-ter, 2) disaster, 3) post disaster, 4) resolution with defined roles, responsibly and communication channels for emergency organisations, tourism organisations and tourism businesses.

Tourist Destination Resilience

According to Tyrrell and Johnson (2008, p.16) tourism resilience is “the ability of social, economic or ecological systems to recover from tourism induced stress” through anticipating fluctuations through their capability to adjust and revolutionize (Peterson et al. 2017). It is vital to building a resilient destination is the resilience of the whole systems (Hall et al. 2018) which covers proper planning and engagement, fair sharing of resources, reducing risk, a strong economy and stakeholder collaboration (Norris et al. 2008; Buultjens et al. 2017). There are some scholars have developed tourist destination resilience such as Cochrane (2010); Ruiz-Ballesteros (2011); Buultjens et al. (2017) and Hall et al. (2018). Cochrane (2010) outlines awareness and control of market forces; stakeholder cohesion; strong and clear leadership and ability to learn, adapt and be flexible. Ruiz-Ballesteros 2011 focuses on capacity to learn and endure unexpected changes; ability to nurture changes for renewal; combining knowledge and sharing resources and developing opportunities for self-organization.

Meanwhile, Buultjens et al. 2017 mentions ability to synthesize the tourism http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

industry into the Disaster Management stages and developing of collaborative networks. Hall et al. 2018 stresses on awareness of the destination vulnerabilities to disasters/stressor; generating opportunities that helps both the vulnerable and invulnerable stakeholders; capability to develop strategic long-term strategy Capacity to adjust processes and collaborate and ability to operate at appropriate regional and local scales. Nevertheless, within the tourism literature, scarce have been studied specifically on destination resilience in the context of Disaster Management (Pyke et al. 2016; Hall et al. 2018). Researchers are becoming more concern of the importance of linking Destination Management, risk alleviation and resilience, thus the importance of this study to address this gap in the literature.

RESEARCH METHODS

Interview

Semi-structured (or open-ended) interviews ensuring a participant serves more as an informant than a participant (Bryman 2002). In semi-structured interviews, researchers usually produce some pre-determined questions asked in a systematic and consistent order. Interviews are conducted in a more conversational style and questions are answered in an order, which is more natural to the flow of general conversation (Berg 2006; O’Leary 2009). Semistructured interviews help obtain the informant’s viewpoint, rather than the viewpoint of the researcher. Another advantage of semi-structured interviews is that they provide both interviewers and interviewees with sufficient freedom whilst concurrently ensuring all relevant themes are addressed (Burns 2000). They ensure that all necessary information can be freely expressed and that any themes arising during the interview will be fully understood (Corbetta 2003).

Secondary Data

Secondary Data can be used to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings from primary data collection (interviews and observation). The secondary data in this study include photos of disasters linked to tourism or activities taken by government and other stakeholders, video clip/footage, maps containing geographical information; blog, Instagram, social media and headlines from newspapers.

Sampling

A non-probability/purposive sampling technique is most frequently applied in case studies (Burns 2000). A specific case is chosen because it facilitates fulfilling the purpose and achieving the objectives of the research and aims at

discovering, obtaining insights and understanding the selected phenomenon (ibid). In other words, researchers’ sample because they need to interview people directly related to the research questions (Bryman 2008). The primary limitation of purposive sampling is the difficulty in establishing at the very beginning how many participants are required for interviews and how many participants make the research representative (ibid). Warren (2002 in Bry-man 2008) stated that, for a qualitative interview study to be publishable, a minimum number of 20-30 interviews are necessary. This suggests that, although purposive sampling is important in qualitative research, the minimum size sample requirements apply. Informants that are going to be interviewed are such as:

Table 1. List of Participants

|

Interviewees | |||

|

No |

Purposes of Interview |

Length of interview | |

|

1 |

Head of Bali's Media Crisis Centre |

Identifying the role of media Centre during crisis in Bali, not solely about tourism but all sectors in this Bali Island |

1,5 hour |

|

2 |

Head of Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force |

Identifying the role and SOP in handling Tourists during volcanic eruption |

1 hour |

|

3 |

Reporter/Journalist |

Having a vantage point of what is going on during volcanic eruption, through her, researchers obtaining information about all involved stakeholders |

1 hour |

|

4 |

Head of Pre-Disas-ter Management |

Identifying the role of Pre-Disaster Management Department |

1 hour |

|

5 |

Head of Disaster Management |

Discovering the role of During Natural Disaster occurred |

45 minutes |

|

6 |

Head of Post Disaster Management |

Discovering the activities after natural disaster happened |

30 minutes |

|

7 |

Head of Bali Tourism Board |

Identifying the role and SOP in handling Tourists during volcanic eruption |

1 hour |

|

8 |

Head of Regional Hotel and Restaurant Associations |

Knowing the impacts of volcano eruption on occupancy in hotels |

20 minutes |

|

9 |

Head of Regional Tourism office |

Identifying disaster mgt plan |

20 minutes |

|

10 |

Assistant manager of five stars hotel |

Identifying disaster management plan related to eruption |

30 minutes |

|

11 |

Head of district hotel associations |

Identifying plan during airport closure |

20 minutes |

|

12 |

Head of District Homestay Association |

Identifying The role of Hotel and Villa during natural disaster occurred |

15 minutes |

|

13 |

Manager of a Tourist Attraction |

Identifying their role during mitigation |

45 minutes |

|

14 |

chairman of the Rafting Association |

Knowing the impact of rafting companies after volcanic eruption |

20 minutes |

|

15 |

the owner of a four-star hotel in Sanur |

Impact of the volcano eruption |

30 minutes |

|

16 |

the business owner of milk pie cakes shop at the departure terminal |

Identifying the impact of airport closure |

15 minutes |

|

17 |

Driver for foreign tourists |

Impact of the natural disaster on his job |

15 minutes |

|

18 |

Room Division Manager |

How his hotel responds to the natural disaster |

20 minutes |

|

19 |

Manager of Five stars restaurant |

Impact of eruption to his restaurant |

15 minutes |

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Researcher divide these findings into several parts such as initial reactions, impact, action/lesson learned from the perspective of tourism stakeholders in order to understand the situation of volcanic eruption in relation to tourism stakeholder.

Initial reactions

As seen on the news on TV and the internet, the Balinese government and tourism stakeholders were not well prepared and equipped to deal with the crisis cause by the eruption of Mount Agung which led to the closure of the Ngurah Rai airport.

“The government of Bali Province cannot guarantee in providing transportation to the airport or neighbouring airport so no one keen to execute or to ascertain whether or who pays the cost of this transportation. The chain of command was not clear. Transportation only arrives at the nearest bus stations without bringing tourists to the neighbouring airports The chaos in

November in the provision of transportation was caused because the mitigation team did not exist at that time” (Head of Bali Tourism Task Force).

This is in line with statements by Drabek (2000) and Ritchie (2009) where despite the devastating consequences that catastrophes can have on a destination, many tourism enterprises and governmental organizations fail to incorporate Disaster Management techniques into their business planning, as they believe the responsibility is not theirs.

However, after chaos in handling tourists occurred in dealing with airport closure, eventually the minister of tourism came to Bali and formed an organisation called Bali tourism Hospitality under which there was a special mitigation team call Bali Tourism Task Force. Nevertheless, there are 22 to 23 groups in the Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force, although they operate independently due to the lack of a clear flow of commands. After doing the simulation several times the mitigation team conducted focus group discussions so the readiness was not only limited to 19 e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Mount Agung but if there was an earthquake or other natural disasters, this Task Force are well prepared.

Furthermore, the Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force is not only divided by the department section but also divided by the stage at which the disaster occurs hence there is a mitigation team then there is also other team such as an information team. This is similar to Faulkner (2001) and Ritchie (2004) work that divided the stage at which the disaster occurs.

Lesson Learned

We benefit from this disaster because we have SOPs on how to handle medium or guest guests when the disaster occurs or when the airport is closed” (Head of Bali Tourism).

Based on the experience in handling of Mount Agung eruption, the Bali Tourism Task Force were finally able to help 2000 guests from Lombok who were affected by the earthquake at Gili Terawangan, Gili Air, Gili Meno. They helped to evacuate tourist from those Gilis and brought then to Benoa harbour and giving them food and drink and providing free transportation to these tourists when they wanted to stay at the hotel book for before leaving Bali.

The Bali Task Force is also able to handle an estimation of 16,000 foreign tourists enter Bali every day and 20,000 domestic tourists enter Bali daily. Evacuation the 16000 foreign tourists are divided into several days. When airports in Bali close, neighbouring airports such as Lombok and Surabaya will be ready to accommodate tourists in Bali or divide these tourists at the two airports.

From the perspective of lesson learned in conjunction with safety and security, an assistant manager from a five-star hotel, giving his statement as below:

“We’ve spent hundreds of millions to buy the reeds. We have 31 villas, and all of the roof’s material are from reeds, if there is a volcano erupting there will be ashes, if the ash gets into the reeds the treatment is really tedious. Finally, the policy of the company to buy a special tarpaulin. If eruption happens, can later close the roof made of reeds. So, we are ready, because of the previous experience at our sister Hotel during the eruption of Mount Merapi” (Assistant manager a five-star Hotel).

The use of Information and Technology

The information is indispensable during crisis, thus tourists must be kept informed about the danger of the possible volcanic eruption.

“In conjunction with the Tourism service during Mount Agung eruption, the most frequent activity is to provide information to tourists that the area is a dangerous area and they should not attempt to enter there. If by chance a tourist is already there, they must know the path to where they assembly if it happened and the volcano erupted. To avoid risk” (Local TV reporter).

It is not merely the information to the end user, in this case, the tourist but the information circulated among tourism service providers are also crucial as it is shown at the below statement.

“For communication we use the WhatsApp (WA) group, in Ubud there is a WA group for the Ubud hospitality help desk and the data is taken from Bali Tourism Board about handling guests and getting up to date information” (Head of District Homestay Association).

In this era of revolution 4.0, the in- real time situation in handling tourists who formation and technology help tourism affected by this disaster.

stakeholders in distributing information Below table is the timeline of erup-

and organising the possible acts that need tion and tourism stakeholders related activ-to be conducted in relation to the natural ities during the mount agung eruptiondisaster such as volcanic eruption. The in- based triangulation between interviews formation from WhatsApp group helps with participants and secondary data from them to know the real time situation about balitourismboard.com.

the issued policy from the government and

Table 2. Timeline of Eruption and Tourism Stakeholder Related Activities

|

18 September |

Bali tourism professionals giving donation at the shelters for those who are participated in Ceremony for mother Earth at the mother Temple of Besakih, which is located at the slope of Mount Agung. This was when alert Level elevated from level 2 (caution) to Level 3 (alert) |

|

27 September |

Bali Tourism Board thanks Airbnb for supporting evacuees of Mount Agung. Airbnb asked those living in in non-affected areas to consider making their homes available to Mount Agung evacuees This information is displayed on their website https://www.airbnb.com/welcome/evacuees/balievacuees |

|

28 September |

Bali Tourism Board took part in Book Donation Drive initiated by the mount Agung Study Tent Group Ten alternative airports were prepared in the case of the eruption of Mount Agung. Estimated 5000 passenger would be affected. The closest airports to be prepared for standby are Praya Airport (Lombok) and Banyuwangi Airport and Juanda Airport (East Java). Immigration department and Indonesian Customs provide tourist Visa Extension service in the case of stayover. |

|

29 September |

BaIi Tourism Hospitality Task Force was established and this organization is funded by the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism. Their tasks: dealing with tourist related services during the eruption. Official website: www.BaliTourismBoard.or.id |

|

1 October 2017 |

All airline offices in Bali are connected to the hotel where tourists stay, hence in the case where airport closes, passengers have options either to extend their stay or transported to the neighboring airports. ITDC, the company that manage 4500 rooms in Nusa dua show their commitment to facilitate any stranded passengers in accordance to room availability and processes in place. |

|

2 October 2917 |

Bali Tourism Hospitality calls on all tourism stakeholders, whether directly or indirectly involved in the tourism industry, to be willing to pray for everyone's safety in this crisis on 5th October. According to Bai Tourism Hospitality Task Force, Tourists who saty in Sanur, 72 kilometers from Mount Agung still enjoying their holiday despite the recent situation The nearest tourist attraction namely Taman Ujung (Ujung Garden) is still allowed to welcome guests despite it is located 12 km from closed zone. |

|

5 October |

The Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force is officially established. They are consisted of three divisions. First division is consisted of Bali hotel Association and Bali Chapter of the Indonesian Hotel and Restaurant responsible for dealing with stranded passengers by proving free room nights. Second Division is Association of Indonesia Tour and Travel Agencies, responsible for transporting the tourists to the neighboring airports. Third division is Bali Tourism Institute, responsible for giving recent information about the eruption and situation, acted as media centre They also create social media account Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/balitourismboard/ Instagram: @OfficialBaliTourism |

|

A visit from Minister of Tourism to ensure the safety the situation in Bali. The minister met the tourists and officials of the Central for Volcanic Geological Disaster Mitigation, the National Search and Rescue Agency, the Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB), and the administration of the Karangasem Regency. | |

|

7 October 2017 |

3 days visit from a group of leading European Travel agents in Bali, supported by Qatar Airways. These travel Agents were informed that the main tourist attractions and favourite destinations are safe. |

|

15 October 2017 |

10 countries (Australia, Singapore, USA, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and India) have published travel advisories for Bali in relation to the eruption of Mount Agung. Only India then to revise its travel advisory after Governor of Bali issuing formal statement about the crisis and had a meeting with general consulates of these ten countries. should an eruption occur, including transportation plans, free accommodation for a limited period at accommodation in Bali. Giving complimentary meals, and how tourists can be transferred by land if Bali’s airport is closed temporarily due to volcanic ash. |

|

20 October 2017 |

Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force set 10 locations for providing assistance and information to tourists in the event of the airport’s closure. These called Hospitality Desk, supervised by 30 lecturers and 150 students from Bali Tourism institute. · |

|

Prior to set these desks, the students and lecturers were trained intensively by the Deputy for Preparedness from the National Disaster Mitigation Agency; Tips for handling complaints by Bali Tour Guide Association; Basic first aid; and trained by psychologists in order to deliver or giving psychological first aid. The training also involve role play in the case of airport closure. | |

|

26 November |

The Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) has raised the status from Orange to Red as a result of the pyroclastic is emitted from the volcano. Flights run by KLM, Air Asia Malaysia Virgin Australia, and Jet Star were canceled as a precaution |

|

27 November |

Official Statement was issued by Bali Tourism Hospitality Task Force regarding to closure of Bali’s Airport Ngurah Rai. Starting from 7:15 Monto 7:00 Tuesday, 28 November. |

|

Tourists were told be calm and no reason to panic and hotel management will keep them fully informed about the situation. For those tourists who were planned to check out from their hotel on Monday to | |

|

Tuesday are advised to speak with hotel’s reception since most hotels are offering the best rate for those requiring to extend their stay. For those who have an urge to leave Bali, an overland journey by coach and ferry from Bali to Surabaya is available. | |

|

28 November |

The Director General of Immigration allowed extensions to foreigners who, because of the absence of a departing flight, extended the period of their original visa. 455 emergency extensions were granted by Bali Airport Immigration office for those two days (27 and 28 November 2017). Major number of extensions were given to Germans (47), Dutch (45) and Australians (44). |

|

29 November |

the emergency visa extension program was put off as a result of availability of flights out of Bali. |

|

2 December |

Students from Bali Tourism Institute have been involved actively and taking part in an active role during the eruption on 27 November (162 students and 33 lecturers help the visitors by providing information at several information desks in Bali. |

|

22 December |

President of Indonesia posted a vlog (video blog) on Friday night stating that Bali is Safe. This vlog was taken during the afternoon when he visited Kuta Beach, this afternoon, I’m on the Island of the Gods, Bali Island,” said the president, adding that Bali is safe. Jokowi then explained that he was on Kuta Beach and repetitively said to the cam-era,”Ramai sekali (it’s so crowded).” the President's visit to Bali proved that the island was totally safe. |

Source: Modified from Bali Tourism Hospitality and adopted some interviews with participants (2018).

CONCLUSION

The volcanic eruption of Mount Agung has taught tourism stakeholders a valuable lesson about the value of working together and the necessity of collaboration between various tourism stakeholders as well as the government in coping with a natural disaster. This experience serves as a valuable lesson, and it has been demonstrated that it can help stakeholders become more vigilant while dealing with the natural catastrophes following the eruption of Mount Agung, such as the earthquake in Lombok. There are some similarities between the natural disaster situation experienced by Bali with the previous research about natural disaster and tourism, specifically, unresponsiveness and the stages of the natural disaster and stakeholder invole-ment.

REFERENCES

ADPC. 2008, Monitoring and Reporting Progress on Community-Based

Disaster Risk Management in

Indonesia, ADPC, Bangkok, p. 28.

BPS, 2019. Jumlah Wisatawan Asing yang Datang ke Bali Menurut Pintu Masuk, 2009-2018. Available from

https://bali.bps.go.id/statictable/2018/ 03/05/46/jumlah-wisatawan-asing-ke-bali-menurut-pintu-masuk-2009-2018.html. [Accessed 8 February 2019].

Berg, B.L., 2006. Qualitative research

methods for the social sciences. London: Pearson Allyn and Bacon

Bhaskara, G.I. 2017. Gunung berapi dan Pariwisata: bermain dengan api.

Jurnal Analisis Pariwisata, 17(1), 3140.

BNPB. 2006, Rencana Aksi Nasional Pengurangan Risiko Bencana 20062009, Perum Percetakan Negara RI, Jakarta.

BNPB, 2019. Bencana alam di Indonesia 1815 S/D 2019. Available from http://dibi.bnpb.go.id/ [Accessed 3 Janury 2019].

Bryman, A., 2008. Social research method. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Burns, R.B., 2000. Introduction to

research. London: Sage

Buultjens, J., Ratnayake, I. and Gnanapala, A. C., 2017. Sri Lankan Tourism

development and implications for resilience. In: Butler, R. W., ed. Tourism and Resilience. Oxfordshire: CABI, 83-95.

Cochrane, J., 2010. The sphere of tourism resilience. Tourism Recreation

Research [online], 35 (2), 173-185.

Corbetta, P., 2003. Social research: theory, methods and techniques. London: SAGE Publications.

Djalante, R. and Thomalla, F., 2012.

Disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in Indonesia: Institutional challenges and

opportunities for integration.

International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment [online], 3(2), pp.166-180.

Drabek, T. E., 2000. Disaster evacuations: tourist-business managers rarely act as customers expect. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly [online], 41 (4), 48-57.

Edoardo, Z., 2018. Lombok projected to lose 100,000 tourists after earthquake. Available from

https://www.thejakartapost.com/news /2018/08/24/lombok-projected-to-lose-100000-tourists-after-earthquake.html [Accessed 4 February 2019].

Fairbairn, T. I. J. 1997. The economic impact of natural disasters in the south Pacific with special reference to Fiji, Western Samoa, Niue and Papua New Guinea. South Pacific Disaster Reduction Programme.

Faulkner, B., 2001. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management [online], 22, 135-147.

Faulkner, B. and Vikulov, S., 2001.

Katherine, washed out one day, back on track the next: a post-mortem of a tourism disaster. Tourism

Management [online], 22, 331-344.

Gayle, D. Bannock, C., 2018. Lombok

earthquake: Britons tell of panic as they evacuate Gili islands. Available from

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2 018/aug/06/britons-stranded-after-lombok-earthquake-tell-of-panic-and-looting. [Accessed 8 February].

Hall, C. M., Prayag, G. and Amore, A., 2018. Tourism and resilience: individual, organisational and destination perspectives. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Handmer, J. and Dovers, S., 2007.

Handbook of disaster and emergency policies and institutions. London: Earthscan.

Huang, J. and Min, J. C. H. 2002. Earthquake devastation and recovery in tourism: the Taiwan case. Tourism Management [online], 23,145–154.

Hystad, P. W. and Keller, P. C., 2008. Towards a destination tourism disaster management framework: long-term lessons from a forest fires disaster.

Tourism Management [online], 29, 151-162.

Kokelaar, P. 2002. Setting, chronology and consequences of the eruption of Soufri??re Hills Volcano, Montserrat (1995-1999). Geological Society

e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

London Memoirs [online] 21(1):1-43.

Murphy, P. E and Bayley, R., 1989.

Tourism and disaster planning. Geographical Review [online], 79 (1), 36-46.

Nguyen, D. N., Imamura, F. and Luchi, K., 2017. Public-private collaboration for disaster risk management: a case study of hotels in Matsushima, Japan.

Tourism Management [online], 61, 129-140.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F. and Pfefferbaum, R.

L., 2008. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology [online], 41, 127-150.

Novelli, M., Burgess, L. G., Jones, A., and Ritchie, B. W., 2018. ‘No Ebola...Still doomed’ - the Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research [online], 70, 76-87.

Schneider, K., 2018. Tourists desperately try to flee Indonesia following earthquake Available from

https://www.news.com.au/travel/trave l-updates/warnings/tourists-desperately-try-to-flee-indonesia-following-earthquake/news-story/b87c64d3c8d66abfc327962562 676f32 [Accessed 6 February 2019].

Skoufias, E., Strobl, E. and Tveit, T., 2017. Natural disaster damage indices based on remotely sensed data: an

application to Indonesia. The World Bank.

Peterson, R. R., Harrill, R. and Dipietro, R. B., 2017. Sustainability and resilience in Caribbean tourism economies: a critical inquiry. Tourism Analysis [online], 22, 407-419.

Prideaux, B., 2004. The need to use

disaster planning frameworks to respond to major tourism disasters. Journal of Travel and Tourism

Marketing [online], 15 (4), 281-298.

Pyke, J., De Lacy, T., Law, A. and Jiang, M., 2016. Building small destination resilience to the impact of bushfire: a case study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management [online], 28, 4958.

Ritchie, B. W., 2004. Chaos, crises and disasters: a strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management [online], 25, 669-683.

Ruiz-Ballesteros, E., 2011. Social-

ecological resilience and communitybased tourism: an approach from Agua Blanca, Ecuador. Tourism

Management [online], 32, 655-666

Tyrrell, T. J. and Johnston, R. J., 2008. Tourism sustainability, resiliency and dynamics: towards a more

comprehensive perspective. Tourism and Hospitality Research [online], 8 (1), 14-24.

UNDP Indonesia 2008a, Lessons Learned – Disaster Management Legal Reform: The Indonesian Experience, UNDP Indonesia, Jakarta.

UNDP Indonesia 2008b, Lessons Learned Indonesia’s Partnership for Disaster Risk Reduction, The National Platform for DRR and the University Forum, Jakarta.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

125

e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback