Code-Mixing in Alternate Universe Story “Tjokorda Manggala” written by @guratkasih on Twitter

on

Journal of Arts and Humanities

p-ISSN: 2528-5076, e-ISSN: 2302-920X

Terakreditasi Sinta-3, SK No: 105/E/KPT/2022

Vol 26.4. Nopember 2022: 413-422

Code-Mixing in Alternate Universe Story “Tjokorda Manggala” written by @guratkasih on Twitter

Chatarina Tri Rahmawati

Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia Correspondence email: rinafelicitas10@gmail.com

Article Info Abstract

Submitted: 9th June 2022

Revised: 5th September 2022

Accepted: 6th October 2022

Publish: 30th November 2022

Keywords: Code-mixing;

alternate universe story; fan fiction; K-Pop; Twitter

Corresponding Author:

Chatarina Tri Rahmawati, email:

DOI:

This research dealt with code-mixing phenomenon in the AU (alternate universe), that refers to fan fiction about one’s favorite celebrity. This type of fan fiction is mostly and largely published on Twitter as a social media platform. "Tjokorda Manggala," authored by @guratkasih, is one of several AUs with code-mixing in every tweet. This study delves deeper into the many sorts of code-mixing employed in "Tjokorda Manggala." It has been shown that 44 code-mixing occurrences were discovered from 28 tweets, with the kind of insertion (75%) being the highest or most usually employed. Alternation (9.1%) is only utilized in a few circumstances, while congruent lexicalization (15.9%) occurred more frequently than alternation. Some factors that caused code-mixing in the AU are settings and situations, participants, topics, and function of interaction. It is intended that through doing this research, the shift in linguistic patterns and how English has impacted Indonesians may be noticed, even in the realm of fan fiction.

INTRODUCTION

The importance of language is undeniable as it is a tool for people to have communication and to give information (Utami et al., 2019). A misunderstanding can even possibly happen as language is much more complicated than a group of words and grammatical rules or structure; it forms a culture of its native speakers (Chen et al., 2006). Being conscious of the importance of a language influences people's propensity to learn many languages and use them in their everyday lives. This has resulted in people becoming bilingual or even multilingual speakers. And being multilingual is no longer unusual in Indonesia, where each area has its own

language spoken by each ethnic group. According to a previous study conducted in 2003, Indonesia has a different language use because, despite the local languages spoken by practically all ethnic groups, individuals must learn the Indonesian language as the lingua franca (Suryadinata et al., 2003). As a result, it can be inferred that the majority of Indonesians can speak at least two languages; the Indonesian language plus the local language of one's community.

The exposure of languages that children get from the environment that they live in makes it easier for them to learn many languages at once (Halsband, 2006). Many studies that have been done mentioned that the way one family uses

languages will shape how children use them as well (Kirsch, 2012; Kopeliovich, 2010). Not to mention how students get exposed in school as the site of cultural reproduction (Tanu, 2016). Education in Indonesia has adopted English and made it one of the subjects taught in schools. Furthermore, the multilingualism trend that has been steadily growing in Indonesia makes schools adopt the system of multilingual policies in their teaching and learning process (Abdurrizal, 2021).

Using this background, it is highly plausible that Indonesians are able to speak using more than one language at the same time, and that sometimes the people will unconsciously speak that way (Sutrisno & Ariesta, 2019). Saddhono and Rohmadi (2014) described how the Javanese language was used in Primary Schools in Surakarta, Central Java, so the students could better understand the material the teachers presented. Even though this phenomenon happened unexpectedly due to teachers’ habit to speak the Javanese language, it was proven to be effective to get students’ attention in the classroom (Saddhono & Rohmadi, 2014). Muslimin (2020) did a study on the Friday prayer sermon in Batu, East Java, that showed how the chaplain changed his language from The Javanese Language to The Indonesian Language at some points (Muslimin, 2020). Another study that was previously done in the southern part of Jakarta stated that the subject of the study used two languages when they were using WhatsApp or Twitter. The languages that were used in this research are English and Indonesia (Jimmi & Davistasya, 2019). This phenomenon (mixing The Indonesian Language and English) has been becoming a popular topic nowadays and even has its own designation that is Bahasa JakSel (South Jakarta’s Language) (Dzakiyyah Rusydah, 2020).

In the field of sociolinguistics, this phenomenon is named as code-mixing.

Taken from Wardhaugh (Wardhaugh, 2006), code-mixing is a phenomenon where people select a particular code whenever they choose to speak and change from one code to another in both long and short utterances. Tripp argued that the reasons behind someone’s choice to switch language can be from various reasons, such as settings (time and place) and situation, participants in the interaction, the topic of the conversational, and interactional functions (Grosjean, 1984). For example, in a company full of people who speak English and Indonesian language at the same time, the employees still call the boss using Bu (Ibu) or Pak (Bapak) even though the utterance is produced in English. This happens as the employees think that the words Ibu or Bapak sound more respectable.

The phenomenon of code-mixing is an interesting topic to discuss as the behavior of the speaker or utterer reflects how globalization and the role of English as an international language influence the language used in a place or a group of people (Meigasuri & Soethama, 2020). The application of code-mixing can also be seen in the media such as talk shows on television, short movies on YouTube, (The Broken Pencils, PRIA, Tilik, etc.) social media, advertisements, and so on. According to Sutrisno and Ariesta (2019), social media, which seems to be inseparable from one’s life, has a big influence in encouraging people to use code-mixing in their everyday lives (Sutrisno & Ariesta, 2019). Social media is an internet platform that allows users to create networks or relationships with others that have similar preferences, histories, hobbies, and so on (Akram & Kumar, 2017). The idea of social media and its effects on one's language policy, or how someone unguardedly mixes

his/her language when speaking, has led the writer to wonder how exactly influencers mix code in their written works on social media. AU on Twitter is a kind of literary work that has recently gained popularity on social networking.

Urban Dictionary describes AU as an abbreviation for Alternate Universe when the fan takes one famous person and makes a story where he or she is unfamous. Basically, AU enables the writer to make their favorite person as someone ‘normal’. The elements of characters written in AU are imaginary. AUs are written and uploaded in the form of Twitter threads, and they usually consist of synopsis, character profiles, and screenshot images from fake chat applications (Caro, 2021). But when there is an AU that is loved by many people, usually the writer will contact a publisher, or vice versa, to make the story into a book version. Some examples of AU that were published as books are Atuy Galon, Rendezvous, Hilmy Milan, and The Cammaro. Specific research on AU itself is rarely or even has never been conducted within the writer’s knowledge which then urged the writer to use one as the subject to analyze. Whereas Twitter as the platform itself is believed as a judgment-free area where its users can talk about numerous things that they enjoy such as music, shows, movie, etc. (Tony, 2016). Twitter is also likable among the youngsters as it is K-Pop fandom gives a massive contribution to this social media as the rise of K-Pop fans all over the globe seems to be unstoppable. In an interview, Jack Dorsey as the CEO of Twitter mentioned that in 2018 itself, there were 5.3 billion tweets about K-Pop (Park, 2019).

As Yulianti, Kurnia, and Adriani (2021) revealed that Indonesian-English code-mixing text is normalized in the society (Yulianti et al., 2021), the writer wanted to analyze how code-mixing

works in an AU entitled “Tjokorda Manggala” by @guratkasih. “Tjokorda Manggala” is an AU which employs Lee Donghyuck or Haechan from a K-Pop group called NCT as its muse.

According to the background stated above, this research was undertaken in order to know about: What types of codemixing are created in the AU entitled “Tjokorda Manggala” on Twitter?, What are the factors that cause code-mixing in the AU entitled “Tjokorda Manggala” on Twitter?

METHOD AND THEORY

Method

This study dealt with and focused on the types of code-mixing analysis in an AU called “Tjokorda Manggala”. As this is a descriptive study, the method that the researcher used in this qualitative research is document analysis in gathering the data. According to Frey (2018), document analysis is “a systematic procedure to analyze documentary evidence and answer specific research questions” (Frey, 2018). Merely 28 of the 35 tweets in the "Tjokorda Manggala" AU are utilized since the writer eliminated tweets that only provide links, trigger warnings, or words summarizing the tale. The documents acquired, inspected, and assessed on the code-mixing typology were then numbered to determine how frequently each form of code-mixing occurred throughout the tale. Most notably, this study focuses on the characters' utterances in the form of a conversation. Thus, the researcher discounted the author’s narration written in Medium.

Picture 1. AU “Tjokorda Manggala”

congruent lexicalization (Muysken, 2000).

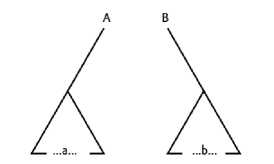

Below are the pictures of how the structure for each type adopted from Cardenas-Claros and Isharyanti’s paper (Cardenas-Claros & Isharyanti, 2009): a. Alternation

Firstly, the researcher read the AU and saved the tweets that used more than one language in them. After that, the researcher classified the types of codemixing written in the AU using Muysken’s theory. For the type of insertion, the researcher gave heed to these categories namely English as the Matrix Language (ML) and Indonesian Language as the Matrix Language (ML) (Namba, 2004). Lastly, the researcher converted the number of each type of code-mixing into percentage.

For the second problem, the writer utilized an informal method to gather the data and explain the findings. Surdayanto (1993) stated that the informal method is a method directed by researchers to present the data by elaborating words and sentences (Sudaryanto, 1993). Using Tripp’s theory, the writer divided the data into four categories with each fit to the reasons on why people code-mix. The four reasons that are used are settings (time and place) and situation, participants in the interaction, topic of the conversational, and interactional functions (in Grosjean, 1984).

Theory

Muysken (2000) argued that there are three types of code-mixing within sentence (inter-sentential code-switching) which are alternation, insertion, and

Picture 1. The structure of alternation from Cardenas-Claros

and Isharyanti (2009)

Alternation is the pattern of codemixing in which both grammar and lexicon are involved. From the example below, the code-mixing occurs when the speaker uses English at the beginning of her sentence and then changes to Indonesian languages to complete her statement. An example quoted from Peñalosa (1985), “Andale pues and do come again” that means “That’s alright then and do come again” (Peñalosa, 1985).

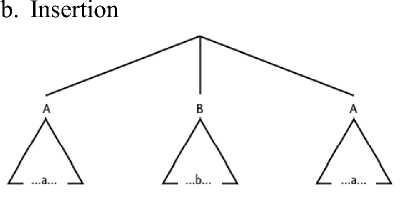

Picture 2. The structure of

insertion from Cardenas-Claros and Isharyanti (2009)

Insertion is the pattern of codemixing in which an embedding happens within the sentence. From the example given below, English words are put (inserted) into a sentence in the Indonesian language. Muysken mentioned that insertion is actually

parallel to (spontaneous) lexical borrowing. For instance, “Yo anduve in a state of shock pa dos días” which means “I walked in a state of shock for two days” (Pfaff, 1979).

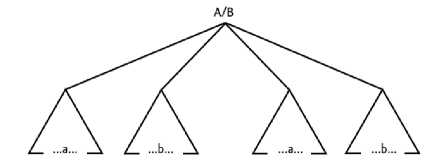

c. Congruent Lexicalization

Picture 3. The structure of congruent lexicalization from Cardenas-Claros and Isharyanti (2009)

Congruent Lexicalization is the pattern of code-mixing in which two languages used in one same sentence share a grammatical structure. From the example given below, English words are put (inserted) into a sentence in the Indonesian language. The grammatical structure in congruent lexicalization can be filled with elements from either language. As for an example taken from Cardenas and Isharyanti (2009), “Software gua buat convert file wav jadi mp3 gua udah expired” which can be translated into “My software that I use to convert wav file into mp3 has been expired” (Cardenas-Claros & Isharyanti, 2009).

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Analysis on the Types of Code-Mixing in “Tjokorda Manggala”

After reading and analyzing the 28 tweets in “Tjokorda Manggala”, the writer found 44 cases of code-mixing from the characters in the story. In these 44 cases, all types of code-mixing (insertion, alternation, and congruent lexicalization) happened. From this data collection, the writer counted the

percentage of each type and present the result in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Types of Code-Mixing in “Tjokorda Manggala”

|

Amount |

% | |

|

Insertion |

33 |

75% |

|

Alternation |

4 |

9.1% |

|

Congruent Lexicalization |

7 |

15.9% |

As seen in Table 4, insertion has the highest number of occurrences in the AU, with 28 examples, accounting for about one-third of the total amount of codemixing in the AU. In contrast, the number of occurrences for alternation is the smallest of the three; only four. "Tjokorda Manggala" does not contain many congruent lexicalizations because they occur just seven times throughout the narrative.

In the case of insertion, an Indonesian language term is offered in a phrase full of English, for example.

-

(1) “I only read the ganteng part.”

-

(2) “Kalau udah otw bandara aku kabarin.”

In (1), ‘ganteng’ means ‘handsome’ in English. Whereas an English abbreviation for on the way (otw) was inserted in a sentence full of Indonesian language (2).

In the AU, there are a few alternations that can be found, such as,

-

(3) “I thought kamu kepengen.”

The speaker, in this case, Manggala started his sentence in English and then finished it in the Indonesian language. This way of speaking is in fact very common for bilingual speakers; starting the sentence in a language and finishing it using another (Poplack, 1980).

Last, for the type of congruent lexicalization, the example can be,

-

(4) “Aku dari kemarin caught up

between work and urus ibu yang lagi sakit.”

In addition to the three types of insertion used in the AU, the writer also sought and examined the two types of insertion found in the AU: insertion with the Indonesian language as the matrix language and insertion with English as the matrix language. In an insertion, when English is the matrix language, it means that English becomes the base or the most used by the speaker when they are speaking. Myers-Scotton (1993) voiced in his study that, “The ‘base’ of the language is called the matrix language (ML) and the ‘contributing’ language (or languages) is called the embedded language (EL)” (Myers-Scotton, 1993). In “Tjokorda Manggala”, the author frequently used The Indonesian Language as the matrix language rather than English as the matrix language. This was proved seeing that 75.5% insertions were made using The Indonesian Language as the matrix language. From the analysis in Table 1, the writer broke down the distribution of those insertions in Table 2 as written below.

Table 2. Matrix Language in the Insertion

Amount %

EML* 8 24.5%

IML** 25 75.5%

-

a. Setting and Situation

Code-mixing can happen based on the settings when the conversation happens, and also based on the situation. Bhatia and Ritchie (2013) said that sometimes a language seems to be more suitable to a particular participant/social group, settings, or topics than another language (Bhatia & Ritchie, 2013; Meigasuri & Soethama, 2020). In the AU “Tjokorda Manggala”, an example for this reason can be found is:

-

(1) “Harus boarding”

This sentence was spoken by Manggala himself and caused by the situation as well as the setting. In the story, the character was in a rush when sending iMess to her girlfriend, Bulan. He wanted Bulan to say something for him, but Bulan was playing hard to get. Therefore, because of the short amount of time that he had and the setting (the sentence was written in iMess, not spoken directly), Manggala chose to use the word boarding instead of harus naik pesawat to finish his sentence. Using English word make it easier and faster for Manggala to convey his message, also he could describe his condition precisely to Bulan.

-

b. Participants in the Interaction

People who are involved in the conversations decide or give influence what languages are involved. Based on the study in Pendem village, the sermon was spoken in the Javanese language (especially Krama alus) because it is the most commonly used language in that area, and the chaplain wanted to make more connections to the listeners by using that language (Muslimin, 2020). One’s language background also takes part in code-mixing. A study done by Tanu in an international school mentioned that one of his subjects of his informed how frustrated he was when his

mother told him to speak in Japanese at home regardless of the fact that his first language is English (Tanu, 2016). In the AU, Manggala is a Balinese and an international surfer. In Bali, there are many foreigners who enable (or even push) the locals to be able to speak English. He comes from a prestigious family as well, so it is not strange at all when he switches from one language to another in an utterance (e.g: Balinese language to Indonesian language or Indonesian language to English). The occurrence of code-mixing due to this reason is:

-

(5) “Tapi tadi aku habis beli teh and

I left my air pods with my bag at the lounge”

-

(6) “I’m outside with your ketoprak”

-

c. Topic of the Conversational

Some things are too ‘sensitive’ or inappropriate to be talked in one’s native language. A proof that can be taken from the AU is as follows:

-

(7) Ini ada two lingerie gift boxes on my mailbox.

It will be embarrassing for Bulan to complete the sentence in her native language. Considering this reason, Bulan chose to finish her utterance in English to disguise the awkwardness that she had.

-

d. Interactional Functions

The last factor that can be the reason behind code-mixing is the function of the sentence; whether it is for demanding, giving information, questioning, etc. The change in code can be used to point up the purpose of the interlocutors when producing the utterance. The examples for interactional functions are:

-

(8) “Sorry gak bilang kalau dari Tokyo aku langsung ke Jakarta.”

-

(9) “Kalau kamu saya kasih

kesempatan, kamu akan stop panggil saya dengan nama-nama panggilan itu?”

The focus of the sentence in data number (9) is that the speaker (Manggala) wanted to apologize for the information he concealed from Bulan. And data number (10) was made by Bulan in hope that Manggala would stop bothering her.

CONCLUSION

After conducting study, the writer concluded that there are certain codemixings throughout "Tjokorda

Manggala," an AU published by @guratkasih on twitter. Insertion is the most prevalent kind of code-mixing (75%), with occasional examples of alternation (9.1%) and congruent lexicalization (15.9%). The author largely used Indonesian Language as the matrix language for the insertion (75.5% of the total insertion).

In terms of the elements producing the code-mixing, the writer discovered that Tripp's assertion fit in "Tjokorda Manggala." Code-mixing occurred because of the settings (time and location) and circumstance (party, graduation, meeting, etc), interaction participants (genders, background,

position), conversational subject, and interactional functions (demanding, giving information).

The explanations above are written in hope that this study increases and helps the readers and future researchers on the code-mixing in a written literature work, especially Alternate Universe.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

A huge thanks for Bella, the owner of @guratkasih, for giving the permission to write this research based on her beautifully written AU. Another big

appreciation for Hilary Mayor as she is the one who inspired me to write this.

REFERENCES

Abdurrizal, M. (2021). Multilingual education policy practices in an Islamic boarding school Indonesia. UHAMKA International

Conference on ELT and CALL (UICELL), 11.

Akram, W., Department of Computer Applications, GDC Mendhar, Poonch, India, Kumar, R., &

Department of Computer

Applications, GDC Mendhar, Poonch, India. (2017). A Study on positive and negative effects of social media on society. International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering, 5(10), 351–354.

https://doi.org/10.26438/ijcse/v5i10 .351354

Bhatia, T. K., & Ritchie, W. C. (2013). The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism 2nd edition. (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

Cardenas-Claros, M. S., & Isharyanti, N. (2009). Code-switching and codemixing in Internet chatting:

Between “yes”, “ya”, and ’si’-a case study. The JALT CALL

Journal, 5(3), 67–78.

https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v5 n3.87

Caro, L. (2021, August 6). Alternate universe: Twitter as a platform for new-age literary pieces. POP! https://pop.inquirer.net/113885/alte rnate-universe-twitter-as-a-platform-for-new-age-literary-pieces#:~:text=AU%20is%20an%2 0acronym%20for,different%20fro m%20reality%20or%20canon.

Chen, S., Geluykens, R., & Choi, C. J. (2006). The importance of language in global teams: A linguistic perspective. Management

International Review, 46(6), 679– 696.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0122-6

Dzakiyyah Rusydah. (2020). Bahasa

anak JakSel: S sociolinguistics phenomena. LITERA KULTURA: Journal of Literary and Cultural Studies, 8(1).

https://doi.org/10.26740/lk.v8i1.33 880

Frey, B. B. (2018). The SAGE

Encyclopedia of Educational

Research, Measurement, and Evaluation.

https://doi.org/10.4135/978150632 6139

Grosjean, F. (1984). Life with Two Languages (An Introduction to Bilingualism). Harvard University Press.

Halsband, U. (2006). Bilingual and multilingual language processing. Journal of Physiology-Paris, 99(4– 6), 355–369.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphysparis. 2006.03.016

Jimmi, J., & Davistasya, R. E. (2019). Code-mixing in the language style of south Jakarta community

Indonesia. Premise: Journal of

English Education, 8(2), 193.

https://doi.org/10.24127/pj.v8i2.22 19

Kirsch, C. (2012). Ideologies, struggles and contradictions: An account of mothers raising their children bilingually in Luxembourgish and English in Great Britain. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15,

95–112.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2 011.607229

Kopeliovich, S. (2010). Family Language Policy: A Case Study of a Russian-Hebrew Bilingual Family: Toward a Theoretical Framework.

Diaspora, Indigenous, and

Minority Education, 4, 162–178.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2 010.490731

Meigasuri, Z., & Soethama, P. L. (2020). Indonesian–English code-mixing in novel Touché by Windhy Puspitadewi. Humanis, 24(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.24843/JH.2020.v 24.i02.p04

Muslimin, A. I. (2020). Code-mixing of Javanese language and bahasa Indonesia in the friday prayer sermon at Miftahul Hidayah osque, Pendem village, city of Batu, East Java. MABASAN, 14(2), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.26499/mab.v14i2 .400

Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual speech a typology of code-mixing.

Cambridge University Press.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Duelling languages: Grammatical structure in codeswitching. Clarendon Press.

Namba, K. (2004). An overview of Myers-Scotton’s matrix language frame model. 10.

Park, S. (2019, March 23). Twitter CEO talks about K-Pop’s affect on Twitter and meets with GOT7’s BamBam, Youngjae, and Mark. Soompi.

https://www.soompi.com/article/13 12094wpp/twitter-ceo-talks-about-k-pops-effect-on-twitter-and-meets-with-got7s-bambam-youngjae-and-mark

Peñalosa, F. (1985). A world-system perspective for Chicano

sociolinguistics. International

Journal of the Sociology of Language, 53(53), 7–20.

https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1985.53 .7

Pfaff, C. W. (1979). Constraints on Language Mixing: Intrasentential Code-Switching and Borrowing in Spanish/English. Language

(Baltimore), 55(2), 291–318.

https://doi.org/10.2307/412586

Poplack, S. (1980). Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en Espanol: Toward a Typology of Code Switching. Linguistics, 18,

581–618.

Saddhono, K., & Rohmadi, M. (2014). A Sociolinguistics Study on the Use of the Javanese Language in the Learning Process in Primary Schools in Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia. International Education Studies, 7(6), p25.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n6p25

Sudaryanto. (1993). Metode dan Aneka Teknik Analisis Bahasa (Pengantar Penelitian Wahana Kebudayaan Secara Linguistis). Duta Wacana University Press.

Suryadinata, L., Arifin, E., & Ananta, A. (2003). Indonesia’s population: Ethnicity and religion in a changing political landscape. In Indonesia’s Population.

https://doi.org/10.1355/978981230 5268

Sutrisno, B., & Ariesta, Y. (2019).

Beyond the use of code mixing by social media influencers in Instagram. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 10(6), 143. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.1 0n.6p.143

Tanu, D. (2016). Unpacking ‘Third Culture Kids’: The transnational lives of young people at an international school in Indonesia. Journal of Research in International Education, 15(3),

275–276.

https://doi.org/10.1177/147524091 6669081

Tony, C. (2016, December 29). How stan Twitter is turning Into a community of bullies. Affinity.

http://affinitymagazine.us/2016/12/

29/how-stan-twitter-is-turning-into-a-community-of-bullies/

Utami, N. M. V., Hakim, D., & Adiputra, I. N. P. (2019). Code Switching Analysis in the Notes Made by the Sales Assisstants in Ripcurl. Lingual: Journal of Language and Culture, 6(2), 20.

https://doi.org/10.24843/LJLC.201 8.v06.i02.p04

Wardhaugh, R. (2006). An introduction to sociolinguistics (5th ed.). Blackwell Pub.

Yulianti, E., Kurnia, A., Adriani, M., & Duto, Y. S. (2021). Normalisation of Indonesian-English code-mixed text and its effect on emotion classification. International

Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12(11). https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2 021.0121177

Discussion and feedback