THE VERNACULAR HIATUS: MODERNITY, TRADITION, AND ETHNICITY

on

THE VERNACULAR HIATUS:

RUANG

SPACE

MODERNITY, TRADITION, AND ETHNICITY

Oleh: Alexander R Cuthbert; Gusti Ayu Made Suartika1

Abstract

The following paper began by serving as a general introduction to this special issue of Ruang – Space. In the course of writing it morphed into a slightly different offering. While a general overview remains, covering linguistic problems and interrelationships, the paper not only offers a basic thesis about Vernacular/Ethnic architecture – thatthe central purpose of vernacular architecture isto inform the present, not to define the past, it also suggeststhe proof. In the course of outlining this idea, works contributed to two former books are cited. The first, Home- A Portfolio of Home over the Ages generated a basic structure for the purpose of analysing the generic features of home. Work previously unpublished is included to reveal the logic and method behind the eight historical chapters in the book. The second Vernacular Transformations – Architecture, Place and Tradition, specifically chapter one, illustrates the development of the thesis in significant detail, and modifies the original model on critique. The article concludes by suggesting that the thesis has been adequately supported, and that the method derived from realist philosophy using necessary and contingent features is useful until someone can improve on this overall system.

Keywords: vernacular; ethnic; necessary and contingent features; counter representation.

Abstrak

Tulisan ini pada awalnya didedikasikan sebagai prolog untuk edisi khusus Jurnal Ruang-Space yang mengambil tema permukiman etnik. Namun dalam proses penyusunannya, telah berubah menjadi artikel yang secara khusus membahas tentang aspek linguistik dan hubungan antar elemen penyusun arsitektur etnik. Artikel ini tidak hanya memaparkan pernyataan mendasar terkait arsitektur vernakular/etnik, tetapi juga menyajikan bukti-bukti pendukung. Sebuah thesis yang diusung disini ialah pemahaman terkait arsitektur vernakular dibutuhkan untuk menginformasikan kondisi-kondisi yang terjadi saat ini, dan bukan untuk mendefinisikan masa lampau. Dalam konteks ini, dua publikasi terdahulu telah dijadikan referensi. Pertama, Home - A Portfolio of Home over the Ages yang dibangun melalui analisa beragam fitur dasar penyusun sebuah 'home-rumah.' Bermacam wujud rumah, yang awalnya belum dipublikasikan, telah dirangkul untuk memahami logika dan metode yang melatarbelakangi penyusunan delapan bab dari buku ini. Kedua, Vernacular Transformations – Architecture, Place and Tradition, khususnya Bab pertama, yang memberikan ilustrasi secara detil, bagaimana arsitektur vernakular dipahami. Di akhir, artikel ini merangkum jika kemunculan thesis di atas telah didukung dengan metode yang dilandasi filosofi seorang realist, dengan memanfaatkan fitur-fitur yang ada. Ini hanya akan berubah jika pernyataan/ide baru muncul, dengan tujuan untuk memperbaiki thesis ini.

Kata kunci: vernakular, etnik, rumah, tradisi

Program Magister Arsitektur Universitas Udayana. Email : ayusuartika@unud.ac.id

Introduction

This paper serves two key functions. It first offers an overview of problems surrounding the use of the term ethnicity as a dominant descriptor.Second it moves forward from these general problems into the realm of theory and method. The first was a monumental, 600 page book called Home -A Portfolio of Home Over The ages, produced in A3 format. Professor Cuthbert co-edited the book and Dr Suartika wrote the first eight historical chapters. The second publication was Vernacular Transformations, edited by Dr Suartika, where Professor Cuthbert wrote the first chapter. This current paper constitutes a continuation of this investigation into a simple architecture with significance far beyond its surface appearance.

One thing that has emerged from prior writing and research, is that this subject is an arena where pictures are important but words almost moreso. While Wittgenstein was correct in suggesting that propositions are better reduced to pictures, the reverse is arguably true here. Before we can speak of ethnic architecture we must examine the terminology that brought it into being in the first place. Words have magical properties. The Ancient Egyptians believed that words did not merely name something after the fact; they actually brought things into existencethrough an act of imagination and creation. This suggests that we need to connect the term ethnic to the ideas associated with it in order to bring it to life.Conversely, there are some ideas we need to eliminate. It is important to recognise that vernacular building is a continuous process, and that it is also being built today.Another hiatus is that people who live in ethnic architecture do not have this name for how they live. Zulu kraals, Italian trulli, Torajantonkonan, Scottish crofts, Inuit igloos and other traditional built forms were/are erected as the only culturally appropriate form of building.None of the inhabitants would say ‘I live in an ethnic building’. So in many cases there is a tendency in architectural circlesto see the vernacular merelyas a historical anomaly- factual but relatively uninteresting. So the termsethnic and vernacular have a tendency to be applied from the outside in, not the inside out. For example the mountain Balinese, who refer to themselves only as Bali Mula are externally denoted as Bali Aga.

In assigning human agency in such a manner, there is a danger of removing the life process of people from the larger structures they inhabit (Giddens 1979). They become alienated in the process, separated as other from the social context both share. Many social anthropologists have now recognised this fact and instead of a process of representation (from the outside in) to define other, the process of counter -representation is deployed whereby an attempt is made to investigatehow people see themselves (Reuter 2002). But anthropologists do not study buildings. So not only do we have to explain how social patterns result in spatial patterns, we must also explain what information the buildings are transmitting. How then did the idea of ethnic or vernacular architecture come into existence? Who defined the other and why was it necessary?In order to cast some light on this situation, wewill briefly address three simple questions. First,‘how can we understand the term ethnic/vernacular architecture both linguistically and relative to theirsemantic environments?’ Second, ‘why is vernacular architecture important at all?’Third, ‘how can we synthesise history and theory in the context of vernacular studies?’

It is quite clear that the term ‘ethnic’ is closely related to at least five other important descriptors, namely vernacular,cultural, indigenous, traditional, and authentic. The term ethnic has origins that are seldom recognised, and it is always meaningful to make this attachment since the use of the name presupposes that its origins are understood. The English language has two main sources, in ancient Greek and in Latin. In this case ethnic stems from Middle English using the Greek term ethnikos that meant heathen or nonbeliever, and was applied to people not of the Christian or Jewish faith. The second level of meaning comes from the Greek word ethnos that means nation. Combining these terms, ethnic then referred solely to the population of Christian nations (since the Jews were de facto stateless). More recently, ethnic has been taken to meanpertaining toa race, nation or tribe that shares the same cultural traditions. But this definition is seriously problematic sincerace is not recognised as a valid descriptor of human groups by biologists.The genetic variation that occurs withinhuman groups (races) is greater than that between them. This is a difficult fact for most populations to swallow.

But the idea that ethnic architecture is racially based is also problematic for other reasons. For example the official United States census only recognises six racial groups, despite the fact that hundreds of different languages and cultures are represented. Similarly there is no nation (e.g. the United States) - that has a uniform architecture of any kind. Race is seriously problematic. But even there the problems do not stop. Ethnic also refers to the language spoken in a particular area by a particular group; or‘of one’s native country’, andin building, it is concerned with the constructionof ordinary homes.On this last item, it is also interesting to note that most ethnic groups (such as the Balinese) do not have architects. The concept architect is an invention of modernity. In Bali the Undagiis part priest, part builder, part counsellor. Hence the question also arises as to whether or not it is correct to speak of ethnic architecture (a term again applied from the outside) or whether it is more appropriate to talk of ethnic building.

The linguistic environment within which the term ethnic sits not only adds to the complexity, it also defines it. Without associated terminology there can be no ethnicity.While the term ethnic architecture is widely used, arguably the term vernacular is more useful than ethnic, since it dispenses with the larger questions of race, nationality etc. The Latin term vernaculus meant native or domestic, which limits the problem somewhat, since there is clearly an overlap between vernacular and ethnic through language. Our tendency is to use both interchangeably, but the preference is for a more precise use of the vernacular, since the indefinable racial dimension of ethnicity is sidestepped.This is clearly significant to Bali within the Indonesian state, since the coincidence of a linguistic group and a vernacular architecture is almost absolute. Culture is also meaningful, despite the fact that most social scientists have given up on the idea of defining culture. There are too many factors to be taken into account (Hobart 2000). This probably explains why most anthropological studies of Bali were limited to specific villages, with Clifford Geertz, Margaret Mead, Adrian Vickers and others preferring to study confined social groupsrather than regional or sub-regional studies such as that of Thomas Reuter.

The term indigenous also has strong associations, meaning native,or belonging naturally to a particular place, rather than to someplace else. This limits the problem even further since indigenous tends to focus on geography rather than social structure. In this case the idea cuts across limitations imposed by ethnicity, caste, class etc., and concentrates to a certain extent on the fact of a shared history as definitive of the formal qualities of place, including its architecture. Tradition is also a limiting factor since it is usually taken to mean being part of the beliefs, customs or ways of life of a particular group of people that havenot changed for a significant period of time. But when we talk of traditional building we also assume the concept of authenticity, some thing genuine where its origins are not in doubt. However what we call traditions in architecture constitute the styles implicit to specific phases of development (modes of production).Architecture built outside of these constraints is viewed as inauthentic or not genuine. So the building of Thames Town in 2010 in Songjiang, China,complete with Norman, Tudor, and Georgian architecture (and a statue of Winston Churchill) would be called inauthentic, since they were constructed under different social and political conditions (King 2004). Conversely, the idea that Balinese traditional architecture based on Hindu precepts is the authentic architecture of the island is false logic. If we accept the idea that vernacular building is commensurate with the construction of ordinary homes, then the Kampong is just as much vernacular to Bali as the traditional courtyard home.So the concept is without doubt, an intellectual minefield.

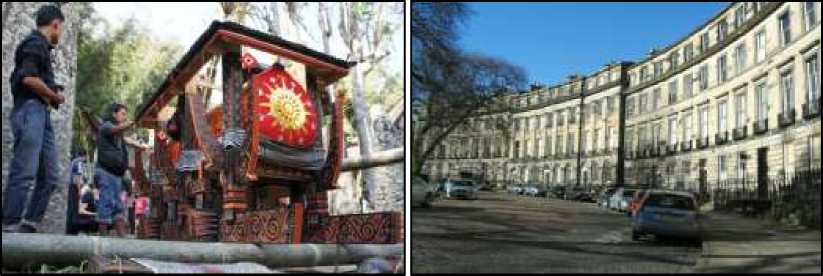

If we look at most ethnic building it is clear that as in all human creativity, considerable talent is exhibited. But it is always talent in relation to an extremely limited palette of materials. The spaces produced are fairly basic with technologyconstrained to simple post and beam construction and spans dictated by stone or wood (around 3 -4 metres).There are of course exceptions. On occasion interesting shapes and forms often emerge as in the Torajan Tongkonan, the tents of the Bedouin, the stilt houses of the Bajau in the Philippines or the Yurts of the Mongolian Steppes (see figures 1 and 2 below).

Figure 1. Torajan Tongkonan. Figure 2. Torajan Tongkonan in construction. (copyright authors)

Nonetheless most recognisable vernaculars are simple structures with clear objectives about geography and the use of materials in the interests of protection from nature – heat and cold, rain, wild animals and other hazards.On occasion beautiful details emerge as in the wood detailing in traditional Japanese or Chinese architecture (See figure 3 below). As a general rule there is little of any real import as far as structure is concerned.

Thatched, slate, bamboo, palm leaves and other immediately accessible materials used for roofing. Stone, brick or wood for structure, frequently no real foundations except for an extension of the main structural elements into the ground (or water as the case may be). But two other aspects of the vernacular far exceed its structural possibilities, namely the organisation of the settlements within which it is embedded, and the nature of symbolic interaction between the home and its environment. In consequence the vernacular is frequently of more interest to archaeologists and anthropologists in explaining the social structures of the time, the nature of rituals and symbolic representation (Oliver 1977, Tjajhono 1998). Social scientists have also made much of the simple bungalow as a universal building form that came out of imperialist expansionism, but such examples are rare (King 1995, Lang 2013). Nonetheless while much can be made of this overall context, the explanations that we have for why we study ethnic building remain relatively closed and also relatively obvious (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Despite these limitations, most architects still recognise that vernacular architecture is important. However in most cases it would seem that it is viewed as a historical curiosity, as a romantic interlude away from contemporary design, or as an elementary expression of early societies where life was simple and unproblematic. There is also a tendency to assume that it is a rural rather than an urban phenomenon, more directly connected to agriculture than industry. This is at least partially true in the case of Bali, where the most coherent examples of such architecture occur in the villages rather than the city and where the rice barn plays an important role in the typology of traditional Balinese buildings (Cuthbert 2012). It is understandable that vernacular architecture has a poor historical record. Fifty years ago there were almost no books produced on vernacular architecture, and it is only recently that it has hadsomewhat of a revival of interest in the architectural community (Brundskill 2000; Carter and Cromley 2005; Oliver 2007; Heath, 2009, Guillery 2010). The reasons for this are prolific.

Figure 3. Example of Ethnic Chinese wood detailing. Figure 4. Vernacular Chinese Ho Tung Home. Figure 5. Typical Chinese tea house or pavilion. (copyright authors)

Prior to the industrial revolution agrarian societies produced countless forms of vernacular building. Due to economic, geographic and social implications, little else could be built. In feudal or proto -feudal societies, only two classes existed that of kings, regents, emperors and other royalty, and that of serfs or ordinary people. In the case of the former, palaces, castles, and villas were built for the upper classes and a mass of vernacular building for the peasants. There was no ‘state’ to speak of since the progression of capital accumulation was still in its primitive phase. The industrial revolution based on the almost unendurable exploitation of working people, changed this

entire system. But it was also characterised by the saying that ‘the rich will do anything for the poor except get off their backs’. It demanded an extended division of labour, a three class system, and a significantly greater need for a greater diversity of architectural forms and spaces. In the twentieth century, modernity massively extended this system yet again,predominantly through shifts in the nature of industrial mass production using Taylorist and Fordist strategies, the increased provision of support for social reproduction (schools, hospitals, recreation facilities, state housing etc.), but also due to the rise of commodity producing culture after the Second World War. Modernity had little time or use for ethnic architecture that was totally unsuited to life in the twentieth century. Indeed in many cases, the vernacular was a situation from which most people sought to escape. It couldnot accommodate the evolutionary changes that were taking place within the capitalist system - from industrial and commercial capitalism to informational capitalism today, nor could it provide the benefitsdemanded by modern life. So it is reasonably safe to say that the vernacular was banished to the fringes of society, both by capital, the state and its own inhabitants whenever other opportunities arose.

But despite the relentless progression of history, a small spark was lit as early as 1753 by the French philosopher l’Abbe Laugier and his Essai Sur Architecture, where he identifies the primitive hut which he claimed distilled the essence of architecture from nature (Figures 6 and 7). Laugier had located the source of what was to become modern functionalism from the most elementary form of building, offering clues as to how the concept of ethnic architecture could expand its meaning as indeed it did within postmodernity. Since Laugier’s Essai was written in French it was by-passed by most architectural theorists and critics right into the twentieth century and was not discussed in any depth until 1962. At that time, several modern architects were becoming aware of the significance of the vernacular and were influenced by it. Frank Lloyd Wright utilised the imagery of the traditional Japanese house, Le Corbusier used images of Greek Cycladic architecture and Scottish Castles were a major influence on Louis Khan. Others such as Mies Van der Rohe, James Stirling and Marcel Breuer remained unaffected by references to the past.

Figures 6 and 7. Laugier’s Primitive Hut – Balinese style (copyright authors).

Fifteen years later post-modernity came into being (if we believe the architectural theorist Charles Jencks, at3.32 pm on July 15th 1972) and with postmodernity, a more welcoming acceptance that the vernacular had something to offer. The reason for this was that

modernist structuralism largely rejected all decoration, symbolism and imagery since beauty was to be experienced directly through function. The function was the meaning.

This formula was rejected by postmodernism that demandedarchitectural expression of symbolic and cultural values, of which Aldo Rossi, Charles Moore, and Bernard Tschumi are prime practitioners (Broadbent; 1996; Gottdiener; 1995; Gottdiener and Lagopoulos 1986; Preziosi 1979b; Krampen 1979).Within postmodernity, the exploration of the vernacular has become significant since it fundamentally reverses the modernist ethos. The structural functionalism of the modernists denied any meaning that was not derivative of structure or function, a position that died with the dynamiting of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St Louis in 1972. For too long modernism had denied that human agency with its archetypal requirements for symbolism, mysticism, codes and texts, could be reduced to an architectural aesthetic that existed only for architects, exemplified by an apocryphal story about Mies Van der Rohe, who reputedly once said ‘If the people tell me what they want I will design for them’ – but the people did not get the chance, so he continued to design for himself. Postmodernity welcomed the fact that buildings like the city constituted texts that could be read and deconstructed to reveal hidden meanings. The corollary of course was that hidden meanings could also be designed into them by architects who were up to the task. One of these methods was to deconstruct the vernacular and incorporate it into built form by various means as suggested above. Classic examples of this are pan-national phenomenon, from Charles Moore representing imagery of the Italian countryside and Roman architecture in the Piazza D’Italia in New Orleans to the New Classicism of Quinlan Terry in England and Rob Krier’s indigenous revivalism in Seaside Florida.

So the bones of the thesis evolved from Home and was further extended in Vernacular architecture.In Homewe first posed the question ‘what are the prime functions of home and what are the generic elements that represent the defining factors in the typological variants of the concept home?’ Given the fact that we had the history of human settlements to contend with, it was impossible to rely on any of the conventional descriptors of home that one might find in any architectural textbook. We recognised that the classic text on the subject was that of Claire Cooper Marcus (1995) but it was written on an entirely different basis to our adopted task. So Home was structured round eight main elements, namely Defense, Nature, Cloister, Spirit, Journey, Art, Façade and Function.It should be noted however that we considered many other categories – family, ritual, worship, machine, tower, palace etc. These were all rejected for different reasons, but commonly because they could all be accounted for in the final chosen matrix. This system was not published in Home and appears here for the first time (Figures 8 and 9).

The original matrix occupied five pages and due to space constraints, the following table has been severely compressed from the original. The basic organising system is indicated in Table 1.

Figure 8. Home as Journey (to the next land). Tonkonan burial ceremony. Figure 9. Home as Façade.Moray Place Edinburgh. (copyright authors)

Table 1. Organising system for the historical sections of home

|

THEME |

1 ARCHETYPE |

2 CONTENT |

3 FORMS |

4 EXAMPLES |

SOURCES |

|

objects/forms |

feelings |

expressions |

typologies |

necessary references | |

|

1 HOME AS DEFENSE |

citadel/ fortress |

protection fear |

security surveillance |

castles kraals |

Cooper Marcus |

|

2 HOME AS NATURE |

landscape, water |

respect worship |

organic integrated |

stilt house |

Rudofsky |

|

3 HOME AS CLOISTER |

square, monastery |

learning constraint |

interior confinement |

ho-tung |

Oliver |

|

4 HOME AS SPIRIT |

meditation, church |

submission sublimation |

sign symbol |

bali home |

Stewart |

|

5 HOME AS JOURNEY |

spaceship caravan |

kinaesthetic freedom |

learning travel |

aborigines apollo space |

Crouch |

|

6 HOME AS ART |

ritual expression |

creativity pride |

mores values |

gaudi tonkonan |

Baragan |

|

7 HOME AS FAÇADE |

street virtual reality |

illusion confined |

standardise repetition |

daly city paris |

Venturi |

|

8 HOME AS FUNCTION |

machine aparatus |

alienation tension |

geometry symmetry |

charreau igloo |

Eisenmann |

Later in Vernacular Transformations (chapter 1) the above matrix was refined into an altogether different and more complex offering. While the precedingtaxonomy had political economy as an undercurrent, the essence of the new system refined the analysis and prior theory by adding a methodological perspective from realist philosophy (Sayer 1984).These methodologies do not contradict one another. In this process there is an attempt to distinguish between the theory/concrete component and the abstract/empirical component which nonetheless inform each other and represent an integrated social foundation for research. This of course may vary depending on the subject matter under scrutiny, but for our purposes the predominant features of each had to be determined. According to this ideology, the basic division was between necessary features and contingent features. Necessary features are those conditions that are to a degree preordained. This idea can be elaborated by analogy in terms of landlord: tenant - the existence of one presupposes the existence of the other. Or as Sayer comments, ‘While having a language is not what causes me to write now, it is a necessary condition of my being able to write’ (Sayer 1984; 113). On the other hand, contingent features are those where no obvious relationships exist, but where they may be explained in theory. For example, a church and a bank may coexist in a central location with no obvious

connection, but may be explained theoretically in their relationship to the state, to building typologies or other factors. We may say that while necessary featuresare fundamental and causal, they are supported, reinforced and possibly explained by contingency, offering connections that are not immediately obvious. Sayer explains this relationship more precisely when he says ‘In order to move from trans-historical claims (e.g. all production is carried out under social relations) to historically specific claims (capitalist production presupposes a property-less class of workers) historical information not implicit in the former has to be added’ (Sayer 1984:142). So it is clear that the move from abstract to concrete cannot be deductive and can only be explained using empirical information derived from contingency. Out of this kind of consideration the following hypothesis emerged-

That the central purpose of vernacular architecture is to inform the present, not to define the past.

Agreement or disagreement with this thesis is not however the point. It is easy to form the hypothesis that apples fall from trees, but yet another thing to supply a thesis as to why it happens. The hypothesis itself can be a very simple statement, but in this case Isaac Newton had to develop a whole theory of gravitation in order to demonstrate what was actually taking place. The same is true with the hypothesis ‘that the atom is not the smallest physical component in the universe’. The congruence of theory with proof is extraordinarily complex. So to support the above hypothesis we set about formulating a satisfying explanation as to how this representation occurs. This became increasingly complex as the vernacular was deconstructed to reveal its true meanings. Some additional questions surrounded the idea.For example is vernacular architecture being built today, or is it confined to history? Does vernacular have an urban or a rural dimension or both? What is its relationship to architectural theory and how does the current proposal alter this? If so are we defining a state or a process? If in fact we are dealing with a process, what kind of process is it?

There are three basic states that can be identified; preservation - retaining original form, function and structure.Conservation - retaining original form, but changing structure and function. Transformation-modifying or changing form, function and structure at will. Each process will of course result in a different kind of architectural typology or building form within which standard variations occur. Given that our search to expose the essence of vernacular transformation on the theoretical assumption that its purpose is to reveal the present, what key dimensions of necessity and contingency can we identify in relation to the vernacular? Below six necessary features and eight contingent features are suggested. These can also be represented in a matrix to define key interactions although thissomewhat oversimplifies the problem, since all possible interactions occur between one necessary condition and all or several contingencies. This reaches the limits as to what can be represented in graphic form.

Necessary features

-

1 Society: typified by class, caste structures.

-

2 Space: geography, density and production.

-

3 Time: historical narratives affecting the present.

-

4 Meaning: semiosis and the deconstruction of texts and discourses.

-

5 Labour: the transformation of nature to functional uses.

-

6 Value: the creation of fixed capital in the form of building.

Contingent Features

-

1 Ideology: the ‘mind set’ guiding production.

-

2 Aesthetics: choices made through the realm of the senses.

-

3 Form: the relation between nature and man mediated in space.

-

4 Function: processes necessary to sustain life.

-

5 Mimesis: learning that occurs through repetition.

-

6 Analogy: direct comparisons between similar events or processes

-

7 Metaphor: the symbolic representation of these processes.

-

8 Totemism: the material representation of spiritual values

Table 2. Necessary and contingent features converted to matrix form

|

Ideology |

Aesthetics |

Form |

Function |

Mimesis |

Analogy |

Metaphor |

Totemism | |

|

Society |

1 |

7 |

13 |

19 |

25 |

31 |

37 |

43 |

|

Space |

2 |

8 |

14 |

20 |

26 |

32 |

38 |

44 |

|

Time |

3 |

9 |

15 |

21 |

27 |

33 |

39 |

45 |

|

Meaning |

4 |

10 |

16 |

22 |

28 |

34 |

40 |

46 |

|

Labour |

5 |

11 |

17 |

23 |

29 |

35 |

41 |

47 |

|

Value |

6 |

12 |

18 |

24 |

30 |

36 |

42 |

48 |

In Vernacular Transformations another eleven chapters explore different aspects of the Vernacular across South East Asia. The above matrix represents a work in progress, and should be taken in that light. Hopefully it will have made some contribution to our understanding of the significance of the vernacular to architectural theory. In the above taxonomy labour and value have been added as necessary features so these changes will be briefly explained below as well as the defining context of both necessity and contingency in the system. Two other details are necessary. First, it should also be noted that a system when perfect cannot be added to – no extra elements are required. But when anything is removed the system will cease to function as a system. Most other collectivities may be described as agglomerations where things may be added or subtracted to no effect.Many doctoral theses fall victims to the inherent differences. Second, the choice of features is dictated by the relationship between abstract and concrete research using the realist method, between theory and empirical investigation, and between the objective and the subjective. These are not opposites but complementary principles that are required for the system to operate across an entire spectrum of relationships.

Necessity and contingency

To a degree, the necessary features noted are somewhat universal. All societies are class or caste based except the most elementary such as the Australian aborigines or the Ituri tribe in Africa. That all societies occupy space is also a necessary truism, but it also lies at the root of much human conflict. History is also a given, despite the fact that many societies chose to write history up in accordance with their own self- image rather than leaving the facts to speak for themselves. The Peruvian Incas are a good example of this, since they had priests whose main job was basically to reinvent history to suit the ruler of the time. We could also argue however that all imperialist nations write history to justify their invasions. Meaning is a pre-requisite for all human societies in whatever form it materialises. So social hierarchy, space, history and meaning (semiosis) are irrefutably significant. In the remaining two, labour and value, it should be noted that in effect these are not new categories but have been separated out from society as critical dimensions that need to be allocated greater importance. Labour is the force that transforms nature into productive environments, vernacular architecture included. At the same time the concept of value pervades society, and this does not merely include material value, but spiritual, moral and ethical values that are necessary for any functioning community.

Contingency has eight dimensions. Ideology is a driving force that is contingent to religion and economy alike, since the economic base of any society will be driven by the specificity as to how human life should be organised and controlled. Aesthetics are significant since few societies are deprived of concepts of beauty and truth. But they can also be used as a set of principles that guide various art forms, rituals, and social tradition. The environment while important also makes architectural forms contingent on geography, politics and other factors. It has no uniformity except when undermined by technology that for example would permit the same home to be reproduced everywhere, assuming that financing and air conditioning was available. Functional processes deployed to sustain life are similarly varied depending on the nature of the prevailing necessary features. The remaining four dimensions of contingency are closely related – mimesis, metaphor, analogy and totemism are vectors of the same need to create satisfying built forms and are particularly meaningful in relation to vernacular architecture. Mimesis means deliberate imitation and copying, usually as part of some creative process, and typifies much vernacular architecture usually in the interests of survival. Analogy designs by a deliberate comparison between events, processes, art forms, architecture and other means. But it also serves as a justification for action assuming that what is being used in the process of transformation is useful and effective. Metaphor is arguably the most complex dimension in creative processes, since no copying or comparative analogy takes place, for the simple reason that a metaphor is fundamentally a symbolic transaction between two processes or events (Kusno 2010). It is a representation of something else that does not necessarily exist in the same time or space but still drives an idea. Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp mentioned above is a metaphor for Cycladic architecture in principle. Finally, the totemism studied by Claude Levi Strauss in a book of the same name is reified in situations where something becomes a totem (image) for something else (Levi Strauss and Needham 1971, Freud 1950). This is different from the direct mimesis of copying something, since a totem can also exist as

a psychological quality where an idea or concept is raised to the level of worship and followed unconditionally.

Figure 10.Torajan totemic representation. Figure 11.Torajan symbolic space. (copyright authors)

Conclusion

This short paper has concentrated on giving both an overview of principles in relation to vernacular and ethnic architecture, as well as outlining a systematic method of study. Interested scholars can refer to an extended version of this paper in Suartika (2013, 7-40). Those who chose to refer to this chapter will find that our preference of necessary and contingent features has been somewhat modified from the original when the inclusiveness of the proposition came under scrutiny. Reflection always promotes change. The test of any significant hypothesis is of course that it is difficult to refute. Any hypothesis that proposes that everyone has two legs, two arms and two eyes is not difficult to prove, so the hypothesis is in fact worthless. Gravitation is of another level entirely. So the framework offered above is available for refutation and improvement. As the scientist Alfred North Whitehead stated some time ago ‘But in the real world, it is more important that a proposition be interesting than it be true. The importance of truth is that is it adds interest’.

We are hoping that the method offered above can indeed add interest, or if not improved, that it can be adapted to other contingent research. Our commitment to such a method is to dispense with the idea that vernacular architecture is merely a historical curiosity, or indeed asan architectural tourist guide to ‘primitive’ building in the developing world. The vernacular cannot be successfully theorised from within itself. But it canbe theorised in terms of its necessary and contingent features until a better method comes to the surface. At the same time we have to move forward. While we now have three supporting levels, a fourth is also required. The first dimension was an elementary grounding suggested in Home. The second level was the outcome of a hypothesis that the fundamental purpose of vernacular architecture was to inform the present. The third dimension was the development of a thesis, a proof informed by political economy but using certain properties of realism - the interrelationships generated by necessary and contingent features. While the fourth dimension is not present in this paper, it has already been sketched out in Cuthbert (2012). In that text, we move from the theoretical to the empirical. What do we do now we have the explanation? It was suggested that for practitioners another four factors were critical in the formation of a true Balinese urbanism ‘the destruction of mythologies, generating a culture of critical regionalism, accepting vernacular transformation as a fundamental building block of any design idiom,

and a committed consideration of the New Urbanism’ (Cuthbert 2012:35). We now have an elementary framework. All that remains is for us to commit to its development in practice, hopefully sooner rather than later.

Bibliography

Broadbent, G (1996) 'A plain man’s guide to the theory of signs in architecture' In Nesbitt K (Ed) Theorising a New Agenda for Architecture New York: Princeton Press.

Brundskill, R W (2000) Vernacular Architecture London: Faber and Faber.

Carter, T and Cromley, E T (2005) Invitation to Vernacular Architecture: A Guide to the Study of Ordinary Buildings and Landscapes Knoxville TE. University of Tennessee Press.

Cooper-Marcus, C (1995) House as a Mirror of Self Berkeley CA: Conari Press.

Cuthbert, A R (2013) 'Vernacular architecture – context, issues and debates' In Suartika, G A M (Ed.) Vernacular Transformations–Architecture, Place and Tradition Denpasar: Pustaka Larasan and Masters Program in Planning and Development, Udayana University, p: 7-37.

Freud, S (1950) Totem and Taboo New York: Norton and Company.

Giddens, A (1979) Central Problems in Social Theory London: Methuen.

Gottdiener, M (1995) Postmodern Semiotics Oxford: Blackwell.

Gottdiener, M and Lagopoulos, A (Eds.) (1986) The City and the Sign – An Introduction to Urban Semiotics New York NY: Columbia University Press.

Guillery, P (Ed.) (2010) Built From Below–British Architecture and the Vernacular London: Routledge.

Heath, K (2009) Vernacular Architecture and Regional Design London: Routledge.

Hobart, M (2000) After Culture, Anthropology as Radical Metaphysical Critique Jogyakarta: Duta Wacana University Press.

King, A D (1995) The Bungalow- the Production of a Global Culture Oxford: Oxford University Press.

King, A D (2004) Spaces of Global Cultures–Architecture, Urbanism, Identity London: Routledge.

Krampen, M K (1979) Meaning in the Urban Environment London: Pion.

Kusno, A (2010) The Appearances of Memory. Mnemonic Practices of Architecture and Urban Form in Indonesia Duke University Press: Durham and London.

Lang, J (2013) 'The Modern Indian Bungalow–Vernacular Antecedents' Chapter 2 in G.A.M Suartika, (Ed.) Vernacular Transformations–Architecture, Place and Tradition. Denpasar.Pustaka Larasan and Masters Program Planning and Development, Udayana University.

Levi Strauss, C and Needham, R (1971) Totemism New York: Beacon Press.

Oliver, P (1969) Shelter and Society Woodstock: Overlook Press.

Oliver, P (1977) (Ed.) Shelter, Sign and Symbol Woodstock: Overlook Press.

Oliver, P (2007) Dwellings: The Vernacular House Worldwide New York: Phaidon.

Preziosi, D (1979) Architecture, Language and Meaning- the Origins of the Built World and its Semiotic Organization The Hague: Mouton.

Reuter, T A (2002) Custodians of the Sacred Mountains. Culture and Society in the Highlands of Bali Honolulu University of Honolulu Press.

Sayer, A (1984) Method in Social Science London, Routledge.

Suartika, G A M (Ed.) (2013) Vernacular Transformations–Architecture, Place and Tradition. Denpasar: Pustaka Larasan and Masters Program in Planning and Development, Udayana University.

Suartika, G A M and Cuthbert, A R (2007) 'Introduction and Chapters 1-8' Home-A Portfolio of Home Over The ages Sydney: Millennium Press.

Tjahjono, G (1998) Indonesian Heritage Architecture Singapore: Archipelago Press.

134

SPACE - VOLUME 3, NO. 2, AUGUST 2016

Discussion and feedback