Questioning Direct Cash Funds Regulation on Village Funds in Province of Bali during Covid-19 Pandemic

on

Questioning Direct Cash Funds Regulation on Village Funds in Province of Bali during Covid-19 Pandemic

Ni Luh Gede Astariyani,1 Bagus Hermanto,2 Ni Made Ari Yuliartini Griadhi,3 Tjokorda Istri Diah Widyantari Pradnya Dewi4

-

1 Faculty of Law Udayana University, E-mail: luh_astariyani@unud.ac.id

-

2 Faculty of Law Udayana University, E-mail: bagushermanto9840@gmail.com

-

3 Faculty of Law Udayana University, E-mail: ariyuliartinigriadhi@gmail.com

-

4 Faculty of Law Udayana University, E-mail: pradnyadee@gmail.com

Article Info

Submitted : 22th May 2022

Accepted : 8th December 2022

Published : 30th December 2022

Keywords :

Direct Cash Fund; Regulation;

Village Fund; COVID-19

Pandemic; Bali Province

Corresponding Author:

Ni Luh Gede Astariyani, E-mail: luh_astariyani@unud.ac.id

DOI :

10.24843/KP.2022.v44.i03.p.02

Abstract

The objections of this article are to describe, analyze, combine, and maintain concurrent relationships between regulations, implementation of Direct Cash Fund regulations at the regional level, and determined or measured factors on Direct Cash Fund by regional governments. This study combined normative and empirical legal research, analyzed legal instruments, and conducted interviews with various apparatus and parties involved in the Direct Cash Fund. This research results demonstrate that Direct Cash Fund was an effective government instrument, both in terms of its regulation and implementation by central and regional governments, in assisting village governments in mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic effect, particularly on the poorest people, and sustaining village development agendas through the new Village Fund scheme within Direct Cash Fund allocation.

-

1. Introduction

The Preamble of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia mandates that poverty countermeasures efforts are inseparable from protecting all Indonesia nations1 to ensure public welfare as divine nations vision combating this chronic problem2. This situation is worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, compelling any government to implement policies that would significantly mitigate the pandemic's impact. Indonesia, continues to face any approach to resolving this issue, particularly poverty at the village level. As part of the reform agenda for national development, the Parliament and Government agreed and passed the Village Law (hereinafter referred to as Law Number 6 of 2014) in 2014, which serves as the cornerstone for village government by ensuring its

continued existence and autonomy for villagers3. This Law places a premium on the Village Fund as a government tool for combating poverty and closing welfare gaps4, particularly at the village level5. Other laws, such as the Law on Regional Government (Law Number 23 of 2014) and the Law on Central and Regional Financial Relations (Law Number 1 of 2022), are also used to synchronize village empowerment in Indonesia, particularly in the context of funding villages to boost development6. Village Fund plays a critical role in advancing anti-poverty campaigns and increasing village contributions to national development.

The COVID-19 pandemic also impacted Village Fund, with new allocations of Direct Cash Fund as part of the central government's intervention to mitigate COVID-19's impact on village development and the poorest people in villages7, in this case through refocusing and reallocating national and regional budgets for COVID-19 countermeasures. Both national and regional income has been severely impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak, particularly in 2020 and 2021 in the Bali Province. Regional income has been affected by low demand for tourism, which caused by closure of national borders for several periods, and fear of this virus outbreak. This situation has direct impact on new paradigm policies for people, particularly by regional and village governments, in budgetary, taxation, health system, and prevention from worse condition over Covid-19 pandemic. The governance practice should be conducted with a wise and effective paradigm to determine policy model and pattern for Direct Cash Fund, especially with refocusing and reallocation with Law Number 2 of 2020 related with Enactment of Emergency Law on COVID-19 Countermeasure, and Minister Regulation Number 6 of 2020 that prioritizing the use of Village Fund in 2020, and 2021, as the legal juridical implementation of Direct Cash Fund for poorest people in village level. The research also examined the village apparatus's capacity and effectiveness in distributing Direct Cash Funds while considering an order, justice, suitability, transparency, and administrative accountability.

In this context, Direct Cash Fund evaluation cannot be separated from public policy evaluation has been recognized with specific terms, including policy evaluation, national wisdom assessment, or program evaluation. Wayne Parsons argued that the evaluation research was divided into two dimensions, including how the policy could be determined and measured according to its fixed purposes and actual policy impact8.

The policy evaluation is considered the latest step in the policy process9. As one of the functional activities, policy evaluation is not only conducted in conjunction with previous activities such as promulgation and implementation; it may also occur for all functional activities throughout the policy process. In this context, policy evaluation may concentrate on the substance of the policy, its implementation, and its impact. Thus, policy evaluation could begin with the formulation of the problem, the formulation of the proposed policy, its implementation, and its legitimacy, among other things10. Policy evaluation has two components: policy formulation and policy implementation. After evaluating a public policy, further action should be taken, such as terminating, amending, renewing, or revoking the policy. While policy evaluation is not the final step in the policy process, it may serve as a springboard for policy formulation (especially for amending the previous policies). Policy evaluation is defined as the activities involved in estimating and assessing a particular policy's substance, implementation, and impact. Policy evaluation was classified as a functional activity in this context and is not conducted in the final step but for all policy processes.

Charles O. Jones defined policy evaluation as an activity that aimed to quantify the benefits of programs and government processes through specific criteria, measurement techniques, analysis methods, and recommendation forms11. While the evaluation considered a range of forms, both internal and external to government, and involved a large number of people with various competencies, experiences, and perspectives, and while the process was scientific, the outcome of the policy evaluation appeared political. Thomas R. Dye defines policy evaluation as a lesson in public policy consequences using a specific concept12. Policy evaluation was defined as an objective, systematic, and empirical examination of the effect of policies and public programs on their intended beneficiaries within a specified proposed purpose context. According to William N. Dunn, evaluation has a definition that is correlated and points to the application value scale associated with subsequent policy and program outcomes13. The evaluation may be used interchangeably with appraisal, rating, and assessment. These steps could be interpreted as efforts to analyze policy outcomes in a fixed-value context; this process is also associated with producing information about the value and benefit of a policy.

Samodra Wibawa was considering four functions of public policy evaluation14, including explanation (the evaluation could be portraying program implementation reality and generalized with relations patterns of certain realities dimension, with identifying the problem, condition, and actors), compliance (the evaluation could be

examined the action that taken by actors, bureaucrat and other actors with standard and procedures that fixed in the policy), audit (the evaluation could be examined the output reality until it could be delivered to the fixed targeted groups, including its deviation), and accounting (the evaluation could be determining the socio-economic impact of public policy). Meanwhile, public policy evaluation serves three functions: it provides valid information about policy implementation or focuses on the instrumental aspect of public policy, it assesses the suitability of the purpose or target with the problem targeted in policy implementation, and it makes any contribution to other policies, particularly their methodology.

The Direct Cash Fund was chosen as the government's instrument to address and prevent the worsening effects of COVID-19 on the economic life, social life, and prosperity of village people15. This fund was directly contributed to the poorest people in this context due to refocusing activities and budget on COVID-19 countermeasures, particularly at the village level. The intention of establishing a Direct Cash Fund in response to this pandemic evolved into a viable strategy for achieving social welfare.

According to the extensive research conducted, no previous research has focused on this issue. In contrast, previous research has concentrated on the Village Fund's legal and political context16, as well as its implementation under normal conditions as mandated by the Village Law17. This research analyzed and argued specifically about the village government's authority to manage the Village Fund and Direct Cash Fund. Second, from a regulatory standpoint, each Village Fund managed in the form of a Direct Cash Fund should be based on defined and fixed regulations; and third, the village apparatus should be implemented to ensure that Direct Cash Funds are distributed in accordance with their intended purpose and village empowerment in the COVID-19 pandemic.

This research combines doctrinal and empirical legal research18 with a qualitative descriptive research design to ensure social realities19 regarding the impact of Direct Cash Funds. The informant was identified through purposive sampling that combined primary and secondary data20, and data were collected through observation, interview, and documentation. Data were then analyzed through data collection, reduction,

visualization, and verification21. Additionally, this research focuses on primary and secondary legal substances, analyzing legal materials about the research's fixed issues22.

This research utilized a variety of methodologies, including a statute-based approach, an analytical or conceptual approach, and a legal fact-based approach. Apart from primary and secondary legal sources, this research relied on interviews with various parties, including the Secretariat of the Bali Province Government, the village apparatus in the Bali Province, and villages that manage Village Fund and the receiver of Direct Cash Fund. These data and legal materials were gathered and analyzed using descriptive, comparative, and evaluative techniques, emphasizing grammatical, systematic, extensive, and restrictive hermeneutics.

-

3. Results and Discussions

The purpose of public policy is to maintain and strengthen public order/stabilizer, promote the smooth development of society/stimulator, adjust any activities/coordinator, or divide any substance or material/allocator23. In this context, achieving policy objectives should be accomplished through instruments, which can be defined as any type of thing that any actor can apply to facilitate the accomplishment of any objective. The Direct Cash Fund as a public policy instrument is defined as financial assistance distributed from the Central Government budget to the poorest people within the cash fund to avert any worsening economic conditions24, and it could be defined as a single social protection scheme based on social assistance. Edi Suharto defined the Direct Cash Fund as a social security scheme that distributes funds to vulnerable parties due to short-term negative consequences of policy implementation25. Indonesia has a diverse social protection system in response to this vulnerable condition; this social protection system encompasses all forms of public policy and intervention aimed at mitigating any risk, vulnerable, or worse condition, whether psychologically, economically, or socially, particularly for the poorest people26.

Any actions or activities proposed by anyone, groups or government within certain environment fields that have any resistance or probabilities on this policy aims to achieve

these fixed targets or purposes27. The Direct Cash Fund belongs to government policy that aims to protect the poorest people28, while other policies assist the government to people, both short term and long term29. Long term policies including Program Nasional Pengembangan Masyarakat (PNPM), Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), Program Jaminan Kesehatan Masyarakat (JAMKESMAS), tuition or scholarship program including Bantuan Operasional Sekolah (BOS) or others that directly impacted the improvement of social welfare, while short term policies including Direct Cash Fund program, Poor Rice program, subsidize oil trade program, and cheap rice market program for labor and state apparatus30.

In relations with Ann Seidman, Robert B. Seidman, and Nalin Abeyesekere related to the legal system model, the Law placed as the instrument to fulfill policy purposes, both to explain the laws or explain activities that supported Law as a public policy instrument is defined into five principles31. First, the main actors or related actors are caused by the policy. Second, the implementation authorities that support compliance. Third, the related parties on the Lawmaking process measure any proposed or limitation of legal or non-legal aspects. Fourth, the law implementation not only focuses on regulations/rule aspects but also relates to other social or other factors, and fifth, feedback process from role actors, implemented actors, or regulators32.

Furthermore, in this context, Antony Allot, as Agus Rahardjo quoted, regards the Law as a tool of legal policy that is hampered from functioning correctly33. First, the Law has been weakened since its inception due to any sanctions imposed by the regulator and any decisions that were required as prerequisites for effective policy implementation. Second, the Law may be slower to reach the fixed object or target when there is a contextual change from social attitude and behavior, particularly concerning ambitious statutory and policy-making processes that are not supported by a sufficient implemented agent and its implementation instrument, as well as social context change after policies have been passed or issued34.

Additionally, it is related to the adoption and majority paradigm toward new Law that does not support legal ability due to the pragmatic approach as the most effective legal and moral approach35. It is also related to the necessity of utilizing indigenous genius or customary with consensus principle followed by social sanctions may be more effective at shifting the effectiveness of policy implementation36. The Direct Cash Fund encountered difficulties during implementation, most notably in the following areas: first, data validity regarding the poorest people had a direct impact on the suitability of Direct Cash Fund distribution to appropriate peoples; second, a lack of active participation by society hampered the program's optimal implementation; and third, from a national finance perspective, Direct Cash Fund policy is viewed as an ineffective policy for managing national funds37. Moreover, Direct Cash Fund policy considers ineffective and inefficient to solving poverty in Indonesia caused by this policy cannot improve welfare standard of poorest people. While, the effectiveness and efficiency of the use Direct Cash Fund policy cannot be measured and supervised caused by weak supervision function, and the Direct Cash Fund policy has tendentious as a social conflict caused in society.

This policy could be implemented with effectiveness and efficiency with implement these steps, first, to manage excellent and systematic fund distribution for the poorest people. Second, there is a need to supervise this fund distribution to prevent any fault and inhibitor of this fund far from planned purposes, and third, this fund should be implemented with fund assistance to create new business and new job fields that could lift unemployed level.

In the context of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia38, the village as the lowest government entity as derived from Article 18B paragraph (2) of the Indonesian Constitution, which recognizes the uniqueness of villages and traditional entities that do not contradict the unitary principle39. In this context, the state-recognized village's existence is inseparable from the government hierarchy40. The village fund is a State Budget fund that was empowered for villages when the National Finance Plan41 was

transferred to the Regional Finance Plan42, and it was prioritized for social development and empowerment with the goals of improving village public service43, addressing poverty, strengthening village economics, and closing inter-village development gaps. As the COVID-19 pandemic widespread and affected whole life aspects, the government is trying to conduct any action to assist social-economic that affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, including with substitute Village Fund allocation mechanism during pandemic, in this context, the Village Fund that focused on the village with Village Budget Plan. After the Presidential Regulation Number 54 of 2020 concerning the Amendment of Posture and Detail of State Budgetary Plan of 2020, the Ministry of Finance with Minister Regulation Number 35 of 2020 concerning the Management of Transfer to Regional Budget and Village Budget on 2020 was declined from 72 trillion Rupiahs to 71,19 trillion Rupiahs or similar with cutting 810 million Rupiahs from the previous budget. It was amended by the Village and Outer Regions Development Ministry by the Minister Regulation Number 6 of 2020 and Minister Regulation Number 7 of 2020 that specifically arrange the management and allocation Village Fund to support prevention and countermeasures of COVID-19 pandemic, and the Village Fund could be applied for Desa Tanggap COVID-19 and PKTD, significantly strengthened with Circular Letter of the Minister of Village Number 8 of 2020.

Due to the pandemic, the government prioritized the Village Fund allocation for two reasons: to strengthen the ability and strength of villages' economic and social income through self-managed infrastructure development through the Padat Karya Tunai Desa (PKTD) system. The second priority is strengthening public health resilience through prevention and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Emergency Law Number 1 of 2020 established a new instrument to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on village economics, particularly in Article 2 paragraph (1) letter I of the Emergency Law Number 1 of 2020, which emphasizes the urgency of budgetary allocation implementation for refocusing, allocating adjustments, and/or cutting or deferring distribution of transfer budget to regional budget and village fund subject to certain criteria. The mainstreaming of the Village Fund in this Emergency Law is related to Direct Cash Funds for the poorest people in villages and COVID-19 pandemic countermeasure activities. This policy was implemented for six months, focusing on 72 trillion Rupiahs or 20% to 30% of the Village Fund budget.

The Direct Cash Fund, which was allocated from the Village Fund, was used to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by providing nominal cash assistance of 600,000 Rupiahs per month to the poorest families that met the criteria for three months and 300,000 Rupiahs per month for an additional three months44, as required by Minister of Finance Regulation Number 50 of 2020, which amended Minister of Finance Regulation Number 25 of 2020. The proposed recipient of this fund is the poorest families, whether they are included in Social Welfare Comprehensive Data/Data Terpadu Kesejahteraan

Sosial or are excluded due to criteria such as not receiving PKH/BPNT/own Prework Card, not having a job and sufficient economic reserves to live on for three or more months, and having a family member who is critically ill. The village may select recipients independently based on these criteria, conduct data processing in a transparent and equitable manner, and be held accountable under applicable Law and regulation. The village may use village data as a baseline and supplement it with Comprehensive Data to identify recipients of PKH and BPNT, or Labourer Department data to identify recipients of Prework cards, or it may use recapitulate social security program data.

Hence, as the normative context, Direct Village Fund policy has objection to prevent any economic and social impact caused by non-natural disaster including Covid-19, within countermeasure policy based from National Village Fund budgetary as enshrined in further in the Article 8, Article 8A, Article 32A, Appendix-1 and Appendix-2 Minister of Village and Outer Regions Development Regulation Number 6 of 2020 juncto Regulation Number 7 of 2020. Moreover, acoording to the Article 24 paragraph (2), Article 24A, Article 24B, Article 25A, Article 25B, Article 32, Article 32A, Article 34, Article 35, Article 47A, and Article 50 Minister of Finance Number 40 of 2020, Direct Village Fund utilization related to Social Security Program and economic impact prevention caused by COVID-19 pandemic as extraordinary case related with disease spread that resist widely to society should be countermeasures with any efforts, including social assistance, with form Direct Cash Fund from Village Fund for the poorest family in the village with following statutory Law and related regulations. These norms were grounded with Law Number 2 of 2020 concerning the issuance of Emergency Law Number 1 of 2020 related COVID-19 countermeasures, while according to the Constitutional Court Decision Number 37/PUU-XVIII/2020 declaring materially unconstitutional conditional including on the phrase “not state finance” (Article 27 paragraph (1)), that has direct links on Direct Village Fund rearrangement caused by Constitutional Court Decision directing reallocation and normalize budgetary posture into normal forms.

-

3.2 The Policy Evaluation perspective on the Village Fund refocusing and reallocation for Direct Cash Fund on COVID-19 Countermeasures in the Bali Province

The Ministry of Village, Outer Regions Development, and Transmigration sets policy on the refocusing and reallocating village funds to prevent and respond to COVID-19 outbreaks in all villages, most notably through Minister Regulation No. 11 of 2019 on Prioritizing Village Fund Allocation for Fiscal Year 2020. In this context, this regulation places a strong emphasis on the allocation and implementation of Village Fund funds in social services, particularly public health. In terms of prevention, the Village Fund aided prevention by educating people; for example, the village apparatus promoted a campaign for health and a clean life cycle for people, with a particular emphasis on preventing the COVID-19 pandemic45. The Central Government Budget Plan allocation could be redirected and reallocated to support a rapid response program designed to mitigate social and economic consequences. Additionally, a new system was created for village apparatus that is adaptable, legitimate, and credible in terms of problem-solving

with local genius and following villagers' needs; additionally, there is an outlook, evaluation, and accountability system that optimizes Village Fund accountability46.

Regarding Regulatory Impact Assessment or RIA, public policy evaluation in this context can be analyzed by focusing on problem formulation, purpose identification, alternative action, cost-benefit analysis, action chosen, and implementation strategy47. This context aims to expand effective regulatory governance, governance management, and market-oriented policy formulation, protecting the environment and promoting social life48. In this context, the Direct Cash Fund from Village Fund was evaluated in isolation from the substance and context of any proposed policy. Evert Vedung focused on eight problem approaches when evaluating any public policy, including a comprehensive purpose problem, an organization (evaluator) problem, a value criteria problem, an intervention analysis problem, an implementation problem, outcome problem, impact (effect) problem, and utilization problem49.

The implementation of the Village Fund before and during the COVID-19 pandemic could be compared in this context to the allocation and distribution of these Village Funds in the Bali Province between 2019 and 2021.

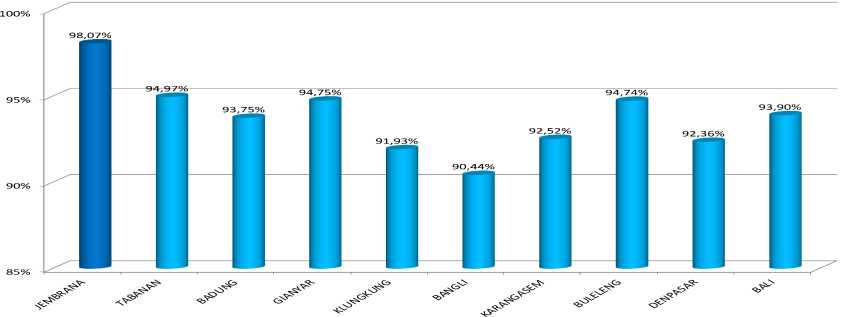

Chart 1. The Percentage of the Village Fund Implementation compared with Allocated Fund for every Regencies/Cities in Bali Province (During 2019 Budget Year)

According to this chart, under normal budgetary form pre-pandemic, Bali budgetary implementation reach 98,07 %, while the lowest regencies that implement Village Fund is Bangli regency (90,44%), and the highest regencies is Tabanan regency (94,97%). In fact, this budgetary implementation on pre-pandemic still below 100% target. While this trends has been continued after Direct Village Fund was issued as budgetary parts on Village Fund, especially as reflected in the table 1, in Province of Bali, the allocation on IDR 679.123.617 has been distributed for each regencies/cities (in Badung Regency at IDR 58.486.546, Bangli Regency at IDR 65.113.263, Buleleng Regency at IDR 130.380.171, Gianyar Regencies at IDR 65.196.455, Jembrana Regency at IDR 54.539.683, Karangasem Regency at IDR 85.289.248, Klungkung Regency at IDR 55.854.813, Tabanan Regency at IDR 124.114.971, and Denpasar City at IDR 40.148.467. This allocation has been increased than 2019 (IDR 591.770.134.640) and 2020 (IDR 647.956.031.983) respectively.

Table 1. The Percentage of the Village Fund Implementation compared with Allocated Fund for Regencies/Cities in Bali Province (During 2020 Budget Year)

|

Regency |

Village Fund allocation under Minister Finance Regulation 35/2020 |

Distribution of National Budget on each regions Village Fund |

Proposed Budget |

Realization on Village Fund |

% than distribute d Budget |

% than Propose d Budget |

|

Jembrana |

51.618.011.000 |

51.618.011.000 |

52.764.384.849 |

51.985.733.993 |

100.71% |

98.52% |

|

Tabanan |

121.485.539.00 0 |

121.485.539.00 0 |

130.747.344.02 4 |

119.085.109.90 4 |

98.02% |

91.08% |

|

Badung |

55.719.888.000 |

55.719.888.000 |

61.101.367.370 |

51.845.996.657 |

93.05% |

84.85% |

|

Gianyar |

61.633.017.000 |

61.633.017.000 |

67.061.972.371 |

64.625.174.297 |

104.85% |

96.37% |

|

Klung- |

53.494.770.000 |

53.494.770.000 |

61.113.070.362 |

52.914.416.955 |

98.92% |

86.58% |

|

kung | ||||||

|

Bangli |

62.757.351.000 |

62.757.351.000 |

67.784.578.547 |

61.010.333.097 |

97.22% |

90.01% |

|

Karang- |

81.803.656.000 |

81.803.656.000 |

89.162.814.948 |

82.533.282.191 |

100.89% |

92.56% |

|

asem | ||||||

|

Buleleng |

125.791.126.00 0 |

125.791.126.00 0 |

136.208.570.37 4 |

127.811.708.66 6 |

101.61% |

93.84% |

|

Denpasa |

36.621.601.000 |

36.621.601.000 |

40.556.027.157 |

36.144.276.223 |

98.70% |

89.12% |

|

r City | ||||||

|

650.924.959.00 0 |

650.924.959.00 0 |

706.500.130.00 3 |

647.956.031.98 3 |

99.54% |

91.71% | |

Source: Data provided by Secretariat of Province of Bali Government (2021).

According to the 2020 Budget Year results shows similar trends with 2019 Budget Year results to the Budgetary allocation on 2021 Budget Year was shrinking, with details allocation enshrined in the table 2, in below.

Table 2. The Percentage of the Village Fund Implementation compared with Allocated Fund for every Regencies/Cities in Bali Province (During 2021 Budget Year)

|

Regencies/Cities |

Village Fund Allocation on 2021 Budget Year |

|

Jembrana |

IDR 54.539.683 |

|

Tabanan |

IDR 124.114.971 |

|

Badung |

IDR 58.486.546 |

|

Gianyar |

IDR 65.196.455 |

|

Klungkung |

IDR 65.196.455 |

|

Bangli |

IDR 65.113.263 |

|

Karangasem |

IDR 85.289.248 |

|

Buleleng |

IDR 130.380.171 |

|

Denpasar City |

IDR 40.148.467 |

|

Province of Bali |

IDR 679.123.617 |

Source: Data provided by Secretariat of Province of Bali Government (2021).

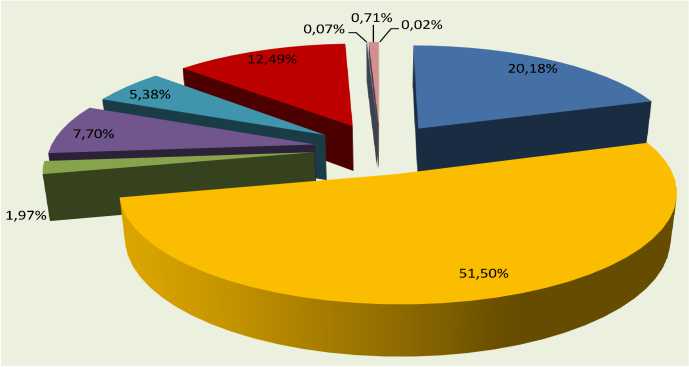

According to these data, between the pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic, the Village Fund, particularly the Direct Cash Fund, was reallocated and refocused on Village Fund between 2020 and 2021. It could be explained in relation to the Village Fund allocation for any field spectrum in this chart.

Chart 2. Allocation of Village Fund during COVID-19 pandemic

Source: Data provided by Secretariat of Province of Bali Government (2021).

Unde

Villag

Infras 73,88 infras 11,66 (0.07 accom

The Direct Cash Fund's impact assessment is centered on the outcomes caused by immediate, intermediate, or ultimate intervention for primary, secondary, or tertiary purposes with implemented policy50. COVID-19 pandemic countermeasures were implemented expeditiously within the Direct Cash Fund, which directly impacted health, economic, social, and other facets of social welfare.

First, the Direct Cash Fund in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic countermeasure effectively prevents squeeze on economic activities, economic impact, budgetary posture, fiscal or taxation, and health mitigation. Moreover, budgetary allocation use was mainly implemented on refocusing and reallocation of budget to prevent COVID-19 impact.

Second, the Direct Cash Fund could improve good and services tender to support COVID-19 countermeasures, shift broader access on authority implementation on operational, technical context as binding from the National Budgetary Plan of 2020, including health tools and emergency hospital, medicines, and other supported costs.

Third, the Central Government established the Direct Cash Fund to collaborate on regional governance to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic, including socialization and social prevention funds for affected people. However, there were differences in the implementation of the refocusing and reallocation of approximately 8,1 million Rupiahs on the Minister of Village and Outer Regions Development Regulation Number 8 of 2020 related to COVID-19 Readiness Villages that hold this budget for padat karya desa, while the Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 3 of 2020 authorized the Regent/Major to delegate to Village Chief shift padat karya desa for COVID-19 social assistance and other social programs. While this issue persists in the relationship between the Circular Letter of the Minister of Village Number 11 of 2020 and the Circular Letter of the Minister of Village Number 8 of 2020 relating to padat karya desa and Village Funds that can be used for Direct Cash Funds, there are distinctions between one regulation's emphasis on poverty as a primary precondition and another regulation's emphasis on COVID-19's impact. Additionally, these regulations impose additional requirements on people who live in houses elevated above the ground and have bamboo walls but lack electricity, creating a problem. Additionally, there is a prohibition phrase for anyone who receives assistance funds from regencies, provinces, and the federal government, among others, creating uncertainty.

Fourth, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the central government to accelerate the Village Fund for new allocations or focus on tackling COVID-19 disease, padat karya tunai desa, and Direct Cash Fund, all of which are Village Funds that automatically affect the minimum standard of Village Fund for all regencies or cities, most notably in the Bali Province. This adjustment prompted regional governments to amend their budgetary plans for 2020 and 2021, respectively, or convert any Head of Regional Regulation to a detailed Regional Budgetary Plan. This amendment reverts Regent and Major to changing the Head of Regional Regulation regarding the capitulation methods for Village Funds and the detailed budgetary implementation for each village's Village Fund.

-

4. Conclusion

The village governance was conducted in accordance with the government's commitment to public service, development, and its authority, to improve social assistance for all societies and assist in relieving social burdens, particularly for the poorest people, through the use of the Direct Cash Fund instrument as a substitute public policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Village Fund allocations into Direct Cash Fund could be determined as social economic prevention policy to support people prosperity and prevented from worse conditions that could be impacted by poor people.

The Direct Cash Fund and its implementation in regions by regional governments are discussed, as are factors that regional governments may consider concerning public service support in regional governance. While, administrative evaluations concerned has been raises cause by data problem that results to wrong people receive Direct Cash Fund and minimum information that provided to public. Moreover, judicial evaluations perspective seems that there are maladministration and nepotism potency over Direct Cash Fund policy implementation.

The suggestion was necessary in relation to Direct Cash Fund during the COVID-19 pandemic as a method for the government to intervene directly in social burden, and this policy could be optimally implemented by combining and integrating all implementing components that understand all regulations and these steps in assistance distribution; it is also a shift in assistance philosophy for all people. In this article, further concrete suggestions also related on more details and concrete program implementation, comprehensive data verifications, Direct Cash Fund cards should be distributed inline with procedural steps that issued, open more Direct Cash Fund distribution spots, and final reports should be provided more clearly on its format and deadline of program implementations.

Acknowledgments

The authors deliver sincere acknowledgments for Editorial Board and reviewers of the Jurnal Kertha Patrika for any assistance and invaluable thoughts for this article improvement. Moreover, acknowledgment deliver to Mr. Yusparizal, M.Pd. and Mr. Ario Hadi, M.Si.(Han.) for any efforts on language, clarity and any grammatical improvement for this article. Finally, our acknowledgments also to Udayana University Rector and LPPM for any kinds of supports and financial aspect on our research under scheme Penelitian Hibah Unggulan Udayana 2021.

References

Books

Agustino, L. (2008). Dasar-dasar Kebijakan Publik, Cetakan Kedua, Bandung: Alfabeta.

Atmaja, G.M.W., Astariyani, N.L.G., Aryani, N.M., & Hermanto, B. (2022). Hukum Kebijakan Publik, First Edition, Swasta Nulus, Denpasar.

Dunn, W.N. (2008). Public Policy Analysis An Introduction, Fourth Edition, Pearson Education Princeton Hall Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Marzuki, P.M. (2008). Penelitian Hukum, Kencana Prenada Media Group, Jakarta.

Nurseppy, I., Paryadi, P., dan Ray, D. (2002). Buku Pedoman Kaji Ulang Peraturan Indonesia, Balitbang Deperindag, Dinas Perindag Bali, PEG, USAID.

Suharto, E. (2009). Kemiskinan dan Perlindungan Sosial di Indonesia, Cetakan Pertama, Bandung: Alfabeta.

Vedung, E., “Evaluation Research”, in: B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, eds., (2006). Handbook of Public Policy, 397-416, First Publication, London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Journals

Antlöv, H., Wetterberg, A. & Dharmawan, L. (2016). Village Governance, Community Life, and the 2014 Village Law in Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 52(2), 161-183, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2015.1129047.

Arham, M.A. & Hatu, R. (2020). Does Village Fund Transfer Address the Issue of Inequality and Poverty? A Lesson from Indonesia, The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(10), 433-442, DOI: https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.433.

Arifin, B. et.al., (2020). Village fund, village-owned-enterprises, and employment: Evidence from Indonesia, Journal of Rural Studies, 79(3), 382-394, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.052.

Astariyani, N.L.G. (2015). Kewenangan Pemerintah Dalam Pembentukan Peraturan Kebijakan, Jurnal Magister Hukum Udayana, 4(4),

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24843/JMHU.2015.v04.i04.p08.

Astariyani, N.L.G. & Wairocana, I.G.N. (2019). Delegation of Governor Regulation in Ensuring Utility and Justice, Jurnal Magister Hukum Udayana, 8(3), DOI: 10.24843/JMHU.2019.v08.i03.p02.

Astariyani, N.L.G., Setyari, N.P.W. & Hermanto, B. (2020). Regional Government Authority in Determining Policies on the Master Plan of Tourism Development, Kertha Patrika, 42(3), 210-229,

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24843/KP.2020.v42.i03.p01.

Astariyani, N.L.G., Griadhi, N.M.A.Y., & Dewi, T.I.D.P. (2021). Bantuan Dana untuk Desa di Masa Pandemi Covid – 19, Prosiding Seminar Nasional Sains dan Teknologi 2021, pp. 016-1-016-5.

Athey, S. & Imbens, G.W. (2017). The state of applied econometrics: Causality and policy evaluation, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 3-32, DOI: 10.1257/jep.31.2.3.

Bedner, A. & van Huis, S. (2008). The Return of the Native in Indonesian Law: Indigenous communities in Indonesian legislation. Bijdragen tot de Taal, Land en Volkenkunde 164(2/3): 165-193.

Bedner, A. & Arizona, Y. (2019). Adat in Indonesian Land Law: A Promise for the Future or a Dead End?, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20(5), 416434, DOI: 10.1080/14442213.2019.1670246.

Boonperm, J., Haughton, J. & Khandker, S.R. (2013). Does the Village Fund matter in Thailand? Evaluating the impact on incomes and spending, Journal of Asian Economics, 25(1), 3-16, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2013.01.001.

Choudhury, N. (2017). Revisiting Critical Legal Pluralism: Normative Contestations in the Afghan Courtroom. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 4(1), DOI: 10.1017/als.2017.2.

de Vos, R. (2018). Counter-Mapping against oil palm plantations: reclaiming village territory in Indonesia with the 2014 Village Law, Critical Asian Studies, 50(4), 615633, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.2018.1522595.

Ernawati, E., Tajuddin, T., & Nur, S. (2021). Does Government Expenditure Affect Regional Inclusive Growth? An Experience of Implementing Village Fund Policy in Indonesia, Economies 9(4), DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040164.

Faried, F.S. & Suparwi, S. (2019). Evaluasi Implementasi Kebijakan Publik terhadap Peraturan Daerah Bermasalah, Jurnal Supremasi, 9(2), 28-38, DOI: https://doi.org/10.35457/supremasi.v9i2.716.

Henley, D. & Davidson, J.S. (2008). In the Name of Adat: Regional Perspectives on Reform, Tradition, and Democracy in Indonesia, Modern Asian Studies, 42(4): 815852. DOI: 10.1017/S0026749X07003083.

Hermanto, B. & Aryani, N.M. (2022). Omnibus legislation as a tool of legislative reform by developing countries: Indonesia, Turkey and Serbia practice, The Theory and Practice of Legislation, 9(3), 425-450, DOI: 10.1080/20508840.2022.2027162.

Hutahayan, B. (2021). Law enforcement in the application of large-scale social restriction policy in Jakarta during pandemic COVID-19, International Journal of Public Law and Policy, 7(1), 29-48, DOI: 10.1504/IJPLAP.2021.115004.

Jensen, C., Wenzelburger, G. & Zohlnhöfer, R. (2019). Dismantling the Welfare State? After Twenty-five years: What have we learned and what should we learn?, Journal of European Social Policy, 29(5), 681-691, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719877363.

Kartadinata, A., Ghifari, M. & Santiago, F. (2021). Criminal Policy of Village Fund Corruption in Indonesia, Proceeding on ICLSSEE 2021, 1-14, DOI: 10.4108/eai.6-3-2021.2306470.

Paellorisky, M.O. & Solikin, A. (2019). Village Fund Reform: A Proposal for More Equitable Allocation Formula, Jurnal Bina Praja: Journal of Home Affairs Governance, 11(1), 1-13, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21787/jbp.11.2019.1-13.

Permatasari, I.A. (2020). Kebijakan Publik (Teori, Analisis, Implementasi dan Evaluasi Kebijakan),TheJournalish: Social and Government, 1(1), 33-37.

Rahardjo, A. (2008). Model Hibrida Hukum Cyberspace (Studi tentang Model Pengaturan Aktivitas Manusia di Cyberspace dan Pilihan terhadap Model Pengaturan di Indonesia, Ph.D. Dissertation Summaries, Semarang: Program Doktor Ilmu Hukum Universitas Diponegoro.

Saragi, N.B., Muluk, M.R.K. & Sentanu, I.G.E.P.S. (2021). “Indonesia’s Village Fund Program: Does It Contribute to Poverty Reduction?”. Jurnal Bina Praja: Journal of Home Affairs Governance 13 (1), 65-80, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.21787/jpb.13.2021.65-80.

Schmiedeberg, C. (2010). Evaluation of cluster policy: a methodological overview, Evaluation, 16(4), 389-412, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389010381184.

Seidman, A. & Seidman, R.B. (2009). ILTAM: Drafting Evidence-based Legislation for Democratic Social Change, Boston University Law Review, Vol. 89, Iss. 4, 435-485.

Siems, M.M. (2008). Legal originality, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 28(1), 147-164, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqm024.

Siems, M.M. & Síthigh, D.M. (2012). Mapping legal research, The Cambridge Law Journal, 71(3), 651-676, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197312000852.

Suartha, I.D.M., Puspitosari, H. & Hermanto, B. (2020). Reconstruction Communal Rights Registration in Encouraging Indonesia Environmental Protection, International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 29(3(s)): 1277-1293.

Suartha, I.D.M., Martha, I.D.A.G.M. & Hermanto, B. (2021). Innovation based on Balinese Local Genius shifting Alternative Legal Concept: Towards Indonesia Development Acceleration, Journal of Legal, Ethical, and Regulatory Issues 24 (7), 111.

Sudiarawan, K.A., Tanaya, P.E. & Hermanto, B. (2020). Discover the Legal Concept in the Sociological Study, Substantive Justice International Journal of Law, 3(1), 94-108, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.33096/sjijl.v3i1.69.

Surachman, E.N. (2020). An Analysis of Village Fund Implementation in Central Java Province: An Institutional Theory Approach with a Modeling Institutional Aspect. Indonesian Treasury Review: Jurnal Perbendaharaan, Keuangan Negara dan Kebijakan Publik, 5(3), 203 – 215, DOI:

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.33105/itrev.v5i3.204.

Sururi, A. (2016). Inovasi Kebijakan Publik (Tinjauan Konseptual dan Empiris), Sawala: Jurnal Administrasi Negara, 4(3), 1-14, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.30656/sawala.v4i3.241.

Tegnan, H. (2015). Legal pluralism and land administration in West Sumatra: the implementation of the regulations of both local and nagari governments on communal land tenure, The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 47(2), 312-323, DOI: 10.1080/07329113.2015.1072386.

Tuori, K. (2013). The Disputed Roots of Legal Pluralism, Law, Culture and the Humanities 9(2), 330-351. DOI: 10.1177/1743872111412718.

Utama, T.S.J. (2020) Impediments to Establishing Adat Villages: A Socio-Legal Examination of the Indonesian Village Law, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 21(1), 17-33, DOI: 10.1080/14442213.2019.1670240.

Vel, J.A.C. & Bedner, A.W. (2015). Decentralisation and village governance in Indonesia: the return to the nagari and the 2014 Village Law, The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 47(3), 493-507, DOI: 10.1080/07329113.2015.1109379.

Vel, J.A.C., Zakaria, Y. & Bedner, A. (2017). Law-Making as a Strategy for Change: Indonesia’s New Village Law, Asian Journal of Law and Society, 4(2), 447–471, DOI: 10.1017/als.2017.21.

von Benda-Beckmann, F. & von Benda-Beckmann, K. (2011). Myths and stereotypes about adat law: A reassessment of Van Vollenhoven in the light of current

struggles over adat law in Indonesia. Bijdragen tot de Taal, Land en Volkenkunde 167(2/3), 167-195.

Wahyudi, S., Achmad, T. & Pamungkas, I.D. (2022). Prevention Village Fund Fraud in Indonesia: Moral Sensitivity as a Moderating Variable, Economies, 10(1), https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010026.

Yusa, I.G., Hermanto, B. & Aryani, N.M. (2020). No-Spouse Employment and the Problem of the Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics 11(1): 214-226, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14505/jarle.v11.1(47).26.

Yusa, I.G., Hermanto, B. & Ardani, N.K. (2021). Law Reform as the Part of National Resilience: Discovering Hindu and Pancasila Values in Indonesia’s Legal Development Plan, Proceedings of the International Conference for Democracy and National Resilience (ICDNR 2021): Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.211221.001.

Internet Source

Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan (BAPPENNAS), “Program Bantuan Langsung Tunai kepada Rumah Tangga Sasaran.” URL:

http://old.bappenas.go.id/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=artic le&sid=169, 6 Desember 2010.

Statutory Laws and Regulations

The 1945 Indonesia Constitution.

Law Number 23 of 2014 concerning Regional Governance.

Law Number 2 of 2020 concerning the Issuance of the Government Regulations of the Lieu in Law Number 1 of 2020 concerning Countermeasures of Covid-19.

Law Number 1 of 2022 concerning Central and Regional Financial Relations.

the Government Regulations of the Lieu in Law Number 1 of 2020 concerning Countermeasures of Covid-19.

Presidential Regulation Number 54 of 2020 concerning the Amendment of Posture and Detail of State Budgetary Plan of 2020.

Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 20 of 2018 concerning the Management of Village Fund.

Minister of Finance Regulation Number 35 of 2020 concerning the Management of Transfer to Regional Budget and Village Budget on 2020.

Minister of Finance Number 40 of 2020 concerning Amendment of the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 25 of 2020 concerning the Management of Transfer to Regional Budget and Village Budget on 2020.

Minister of Finance Regulation Number 50 of 2020 concerning Second Amendment of the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 25 of 2020 concerning the Management of Transfer to Regional Budget and Village Budget on 2020.

Minister of Village and Outer Regions Development Regulation Number 6 of 2020 concerning Village Fund on Covid-19 Countermeasures.

Minister of Village and Outer Regions Development Instruction Number 1-2 of 2020 concerning the Acceleration of Direct Cash Fund of the Village Fund.

Minister of Home Affairs Instruction Number 3 of 2020 concerning COVID-19 Countermeasure in Village by the Village Budget Plan.

Jurnal Kertha Patrika, Vol. 44, No. 3 Desember 2022, h. 265-283

Discussion and feedback