Fragmented Approach to Spatial Management in Indonesia: When it Will Be Ended?

on

Vol. 43, No. 2, Agustus 2021

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.plip/kerthapatrika

E ISSN 2579 9487

P ISSN' 0215 899X

Fragmented Approach to Spatial Management in Indonesia: When it Will Be Ended?

I Gusti Ngurah Parikesit Widiatedja1

1 Faculty of Law Udayana University, E-mail: parikesit_widiatedja@unud.ac.id

Info Artikel

Submitted: 6th April 2021

Accepted: 21st June 2021

Published: 1st July 2021

Keywords:

Fragmented Approach; Spatial

Planning; Spatial Management;

Indonesia

Corresponding Author:

I Gusti Ngurah Parikesit Widiatedja,

E-mail:

parikesit_widiatedja@unud.a c.id.

DOI :

10.24843/KP.2021.v43.i02.p03

Abstract

As a regulatory tool, spatial planning is important as it directs socio-economic development and prevents environmental and social damage by commercial and public projects. There should be an integrated spatial management to ensure the effective use of restricted spatial resources, balancing infrastructural, industrial and commercial business development with the available resources, including land, forest, and marine. However, the fragmented approach to spatial management has been thrived since the independence of Indonesia. The newly controversial Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation has emerged a big hope that Indonesia will end the fragmented approach to spatial management. However, this Law seems to maintain this approach by enacting four different governmental regulation for four spatial issues, namely land use planning; forestry; energy and mineral resources; and marine and fishery. This fragmented approach has adverse consequences as it leads to overlapping authorities that may end up with disharmony and conflicting regulations. Besides, the insistence to employ fragmented approach to spatial management has linked to oligarchy issue as shown by old older, new order and the regional autonomy era.

-

1. Introduction

Spatial planning is crucial as it directs appropriate development and the ability to respond to infrastructure pressure due to increased commercial demand.1 By planning how spaces within a particular province, city or an entire country are protected, societies can advance the quality of people’s life, create livelihoods, encourage sustainable economic growth, and shield the environment.2 Spatial planning relies on

an interdisciplinary collection of professions to work effectively, including planners, lawyers, engineers, and public policymakers. Even, within a single discipline such as law, spatial planning traverses’ various fields, including constitutional, administrative, environmental, construction and planning law.

As a regulation, spatial planning contains thoughtful government action 3 to assign, arrange, and balance space for various uses.4 McAuslan explains the main legal issues discussed in spatial planning to include: area and boundaries jurisdiction; the ‘who-does-what’ inquiry (conflicts between authorities); the land inquiry (who has power over the land and who distributes plots for development); planning dealings; and housing settings and their enforcement.5 In this context, contemporary spatial planning has altered traditional ideas of planning, focused on land use distribution and design and prioritizing restraint and control, toward more positive and holistic concerns, needing multi-sectoral and multi-scalar understandings.6 Hence, spatial planning regulation covers not only land use, but also social, economic, and environmental considerations7 by integrating government policies concerned with, among other areas, marine, forestry, agriculture, transport, and energy production.8

Based on above-mentioned perspective, there should be an integrated management in spatial planning. An integrated spatial planning regulation can ensure the effective use of restricted spatial resources, balancing industrial and commercial business development with the available resources, encompassing natural resources, water, air and soil.9 Spatial planning regulation has, therefore, become vital to ensure sustainable development by preventing development from which present and future generations will not be able to recover, or could only recover at a very high cost.10

Historically, the government of Indonesia acknowledged the importance of integrated management on spatial planning. For example, the preamble of Spatial Planning Law (SPL) 1992 expressly specified that “the management of many varieties of natural resources and land, sea and air, must be coordinated and integrated by developing a

spatial policy…”.11 However, at the implementation stage, the central government unilaterally claimed that SPL 1992 was only applied to land management, excluding land that was classified as forest by the Ministry of Forestry.12 Likewise, in the mining, oil, and gas sectors, the central government grants exploitation permits to private companies through production sharing contracts.

This practice has been continued in the reformation era and the fragmented approach to spatial planning is thriving. The newly enacted SPL2007 does not apply to forest areas. Instead, the central government has declared Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry as the legal basis for forestry management in Indonesia,13 granting monopolistic authority to the Ministry of Forestry to plan, use, and control forest areas in Indonesia. In coastal area, there is Law No. 27 of 2007 on the Management of Coastal Areas and Small Islands, and the Ministry of Marine and Fishery has the authority to grant the right of cultivation over coastal areas.

The newly controversial Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation has emerged a big hope that Indonesia will end the fragmented approach to spatial management.14 Article 17 point 2 expressly states that “spatial planning for the national territory includes jurisdiction and national sovereign territory which includes land space, marine space, and space air, including the space within the earth”.15 However, this Law appears to be inconsistent when it says that management of marine and airspace resources regulated by a separate Law. 16 Moreover, the government then issues 4 different regulations to implement Job Creation Law concerning spatial management, including Government Regulation No. 21 of 2021 on Administration of Spatial Planning; Government Regulation No. 23 of 2021 on Forestry Management; Government Regulation No. 25 of 2021 on Energy and Mineral resources; and Government Regulation No. 27 of 2021 on Administration of Marine and Fishery. The issuance of different laws and regulations has indicated the continuity of fragmented approach to spatial management in Indonesia.

The paper asks two central questions to identify and analyze this fragmented approach to spatial management in Indonesia. First, how the fragmented approach to spatial management has been practiced since the independence of Indonesia; and what are the legal consequences of this approach to spatial management in Indonesia?

Indonesia needs a comprehensive and integrated spatial management to anticipate adverse consequences arising from economic and political pressures. The increase in commercial development in Indonesia demonstrates just how important effective

spatial planning laws are. Fragmented approach tends to create overlap authority and conflicting regulations. It will also weaken the coordination process among government authorities at all levels. As a result, this nation may not move quickly to be able to adapt to the increasingly dynamic and complex world settings.

This discussion is relevant to indicate the longstanding failure of current spatial planning regulations, particularly to integrate spatial management in Indonesia. This unresolved problem has led to, among other things, conflicting regulations issued by different ministries, government levels, and the lack of coordination between them in implementing spatial planning regulations in Indonesia.

Some scholars stated that fragmented approach in the legal context may end up with the failure of laws and regulations in reaching their regulatory objectives. Fuller explained “eight ways to fail to make law” including the following: Failure to establish rules at all, leading to absolute uncertainty; failure to make rules public to those required to observe them; improper use of retroactive lawmaking; failure to make comprehensible rules; making rules which contradict each other; making rules which impose requirements with which compliance is impossible; changing rules so frequently that the required conduct becomes wholly unclear; and discontinuity between the stated content of rules and their administration in practice.17 This theory can be used to explain, among others what the consequences of fragmented approach to spatial management in Indonesia.

Gunnar Myrdal introduced “sweeping legislation,” showing all developing countries, in various degrees, are “soft states” because of the hastiness in drafting legislation, leading to what he stated as a defect in law. 18This theory can be used to explain the hastiness of the issuance of Job Creation Law and its governmental regulations that discourage the integration of spatial management in Indonesia.

Although Indonesia had declared its independence in 1945, the Dutch were not expelled from Indonesian territory until 1949. Following the Renville Agreement of 17 January 1948, Soekarno’s administration was given de facto control over Central Java, Yogyakarta, and Sumatra.19 The Dutch maintained sovereignty over the remaining parts of Indonesia.

During this period, in 1948, the Dutch government issued a Town Planning Ordinance or Staadvorming Ordonatie (SVO) followed by its implementing regulation, the

Stadsvormings Verordening (SVV), in 1949.20 The goal of the SVO was to authorize local government to secure the development of towns while complying with social and geographical features and estimated growth.21 The SVV set out in detail the obligations of local governments to provide general and detailed spatial planning,22 especially related to technical rules about road and building construction.23 At this time, the SVO and SVV enabled local governments to actively participate in the planning process as a reflection of a federal system being pushed forward by the Dutch.24

After Indonesia was fully independent in 1949, the administration of the first president, Soekarno (1945-1966), was reluctant to incorporate the SVO and the SVV into national law. The government argued that they were a part of Dutch land law and only fitted within Dutch colonial municipal (gemeente) governance.25 Equally, it was thought that the SVO and the SVV had created western enclaves by segregating space on racial lines.26 Despite this, the SVO and the SVV remained on the books, but were not implemented.

The central government did enact Law No. 5 of 1960 on the Basic Agrarian Law, which is still binding for land administration and allocation in Indonesia. This Law introduced “rights controlled by the State”, meaning that the State is granted authority to regulate and implement the utilization and reservation of earth, water and air space, including natural resources in it.27 This law covers land administration as well as forestry and mining. Soekarno had the opportunity to use this law to integrate spatial management in Indonesia, but never did so. Instead, Soekarno appointed different ministers to manage different natural resources, such as gas, oil, mining, and forestry sectors.28

Under Soeharto’s administration (1966-1998), the SVO was implemented in 1976 when the government issued a Presidential Instruction requiring local governments to enact regulations for city plans.29 Although local governments could issue spatial planning regulations, the process of issuing these regulations was strictly supervised and

authorized by the central government, reflecting a very top-down and centralized approach to spatial planning.30 When drafting the district spatial plan, the district government was required to consult the Provincial Development Planning Board or Badan Perencanaan dan Pembangunan Daerah (Bappeda) and Urban Development Board or Badan Pengembangan Kota (Bangkota) to check whether the draft had complied with the spatial plan at the provincial and national levels.31 Next, the draft was sent to the Directorate General of Public Administration and Regional Autonomy of the Ministry of Home Affairs. If this ministry agreed, the draft was adopted by regional regulation and then submitted to the Minister of Home Affairs for validation.32

In 1987, the central government enacted Government Regulation No 14 of 1987 on the Delegation of Parts of Central Government Authority in Public Works to the Regions.33 However, this still reflected the dominant role of the central government because the Ministry of Home Affairs would analyze the financial and technical capacity of regions before receiving spatial planning authority from the central government.34 Furthermore, the Ministry of Public Works had authority to formulate district spatial planning,35 and the discretion to decide how and when spatial planning authority would be delegated to the regions.36

As regards access to land for commercial development, the central government introduced regulations regarding site permits and the permit-in-principle. The Ministry of Home Affairs created site permits for land acquisition for domestic and foreign investment, including tourism.37 In 1990, the National Land Agency or Badan Pertanahan Nasional (BPN) took over this role, explaining that it had the power to control access to land through the application of the site permit.38 Next, the Investment Coordinating Board or (Badan Koordinasi Penanaman Modal (BKPM) took over the regulation of the permit-in-principle.39 Through this, an investor in the tourism sector could obtain a temporary permit to embark on tourism business activities, including the commencement of preparatory measures stipulated for the formation of the business.40 Hence, an investor had to acquire the permit-in-principle before applying for the site permit.

The existence of a site permit, or a permit-in-principle, had no connection with broader spatial planning principles, and district governments had no power to control land use. As long as the investor had been issued with a-permit-in-principle and a site permit by the central government, the investor could start operating the business, even if the location violated spatial planning regulation at the district level.

In 1992, the Soeharto government enacted the first statute made by the central government concerning spatial planning. Law No. 24 of 1992 on Spatial Planning (SPL 1992) officially replaced the SVO and the SVV.41 SPL 1992 divided spatial planning into the following categories:

-

a. the national spatial plan;

-

b. provincial spatial plans; and

-

c. municipal/district spatial plans.42

Each spatial plan had to determine cultivation areas and protected areas; the norms and criteria of spatial use; and guidelines for controlling space utilisation.43 As regards permits for spatial utilization, the new law allowed the Governor or head of each district to declare void any permit in relation to spatial utilization if it contradicted the district spatial plan.44 Equally, the district spatial plan became the basis for assessing any application for development location permits, proposed by government agencies or private companies.45 However, the central government still had a dominant role in spatial planning governance. As in the previous period, the central government did not allow district governments to autonomously regulate spatial plans. Through the Ministry of Home Affairs, it strictly supervised the creation and the implementation of district spatial plans.46 For these reasons, this period continued the centralized approach of spatial planning that had existed since Soekarno’s administration.

As regards investment, the Law indicated which business sectors were prohibited or open to investment.47 If a sector was not prohibited, an investor might request a confirmation letter from the Governor on the future site of the project.48 After receiving this letter, the investor could seek a permit-in-principle from the BKPM.49 The Governor might then issue the site permit, allowing the investor to start the land acquisition process.50 Before issuing the permit, the Governor was required to refer to the existing district plan. Hence, there was a connection between the permit-in-principle, the site permit and spatial planning.

Soeharto continued the established fragmented approach to spatial management in Indonesia. He was reluctant to integrate spatial arrangements, as the exploitation of natural resources through this approach became the central government's main source of income.51 If spatial management was integrated, the central government would be forced to renegotiate existing production contract sharing agreements in mining, gas

and oil, and existing concessions in forestry management, and this would adversely affect the public-private business network, the pillar of the Soeharto regime.52

Following the fall of Soeharto in 1998, Indonesia began a period of transition known as Reformasi. The reforms of this era, and the openness they created, led to criticism of SPL 1992 as no longer suitable for an Indonesia that was transitioning to a more democratic model. In this era, it became clear that a regulatory adjustment was needed to divide spatial planning powers differently between the Central and regional governments.53 A further critique of SPL 1992 was that it did not contain controlling and enforcement mechanisms. As a result, spatial use often did not follow the requirement of spatial plans.54 The following section will further explain all spatial planning laws and regulations in this era as they try to respond to the drawbacks of previous fragmented approach to spatial planning regulations in Indonesia.

The most important features of SPL 2007 included: the sharing of responsibility for spatial planning between the Central, provincial, and district governments; the enhancement of controls over spatial planning; public participation; and the introduction of administrative and criminal sanctions for violations of the law.

This law defines spatial planning as “a system for the process of spatial planning, space utilization and control over space utilization”.55 The State is obliged to manage the spatial use “for the greatest benefit of people’s welfare”.56 Regulating the use of space, this law divides spatial use into “spatial structure” or struktur ruang and “spatial design” or pola ruang.57 “Spatial structure” is defined as “an arrangement of residential centers and infrastructure network systems that function as a support for the society’s social and economic activity”.58 Meanwhile, “spatial designs” are defined as “the spatial allocation that divides areas into conservation and cultivation areas”.59

This Law then defines “an area” as “a region that functions mainly for conservation or utilization”.60 “Conservation areas” are areas that have the primary function of ensuring environmental sustainability of natural and human-made resources (such as a residential area).61 A “utilization area” is “a region whose primary function is utilized because of the existence of natural resource potential, human resources, and human-made resources”.62

There are also national, provincial and district “strategic areas”. A “nationally strategic area” is a “region that has a priority in spatial planning due to its important influence for state sovereignty, defense, and security, the economy, society, culture, and the environment, including regions classified as a part of world heritage”.63 A “provincial strategic area” is a region that has priority due to its economic, social, cultural and/or environmental importance to a province.64 A “district strategic area” is a “region that is prioritized because of its economic, social, cultural and/or environmental importance to a district”.65 The existence of strategic areas reflects the application of “growth poles”, where the national, provincial, and district governments focus on the development of a specific pole (or region) due to economic, social, and environmental considerations.66

Given the implementation of regional government, scholars might expect that Indonesia would follow the typical nature of spatial planning in most developed countries, where it operates principally at regional or at the state level rather than centrally. However, SPL 2007 has maintained the centralized character of the previous spatial planning laws in Indonesia. In fact, this Law expressly states that “national, provincial and district spatial planning governance shall be performed in a hierarchical and complementary manner”.67 As a means of integrating national development, the central and provincial governments have authority to issue general guidance and binding directives in relation to spatial plans.68 The district governments must follow all of these guidance and directives, particularly when drafting spatial plans.69 The draft district spatial plan must also refer to national and provincial spatial plans.70 Once it has the Governor’s recommendation, this draft must acquire prior approval from the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning.71

The only new authority granted to district governments is to control land acquisition for commercial activities. SPL 2007 expressly states that the district spatial plan is a legal basis for issuing site/location permits and land administration.72 This provision allows the district government to reject an application for a permit if it violates the existing district spatial plan, even if the applicant has been granted a permit-in-principle from the BKPM.73 However, this new authority has caused problems on regionalism and the hierarchy of laws.

There is also a lack of coordination where district governments do not involve the provincial government in the issuance of location permits. In addition, the provincial government has no power to revoke the location permit if it contradicts the provincial spatial plan. Moreover, as a result of a 2015 Constitutional Court or Mahkamah Konstitusi (MK) decision, the central government, through the Ministry of Home Affairs, is now no longer able to cancel regional regulations.74

SPL 2007 grants authority to the national, provincial, and district governments to issue spatial plans, both general and detailed plans, and strategic areas.75 “General plans” comprise national spatial plans, provincial spatial plans, and district spatial plans.76 Meanwhile, “detailed plans” cover the following issues: “island spatial plans/archipelago and national strategic area spatial plans; provincial strategic area spatial plans; and district detailed spatial plans.”77 Detailed plans are an operational tool to arrange spatial plans. They include a detailed explanation of the blocks, zones, and areas in a particular district, identifying which areas are opened or closed for particular projects.78 After five years, governments can re-evaluate general plans.79 Any general plans shall “retain any forest areas to, at least 30 per cent of the total watershed area” within national/provincial/district areas in order to protect the environment.80 For example, the Head of the East Java Provincial Agency states that East Java has forest areas of 2.25 Million Ha, that is, 41 per cent, so it has complied with SPL 2007 and Forestry Law.81

SPL 2007 tried to solve problems in SPL 1992 related to the fact that it had no enforcement procedures in its provisions. It introduced enforcement mechanisms to control spatial utilization by imposing zoning regulations, permit systems, incentive and disincentives, and sanctions.82 In addition to securing the fulfilment of spatial planning, there must be a mechanism to monitor, evaluate and report on the implementation of the spatial plan.83 This process involves the public, who can submit reports and complaints to the government.84 Should the outcome of the monitoring and evaluation show administrative misconduct, the Minister, Governor and Mayor must undertake necessary administrative measures to stop such misconduct.85

There are administrative and criminal sanctions in SPL 2007. Anyone who violates the regulation will receive an administrative sanction,86 which could be “written

reprimands; temporary suspension of activities; temporary suspension of public services; closure of (business or development) site; revocation and cancellation of license; demolition of constructions; rehabilitation of land; and/or fines.”87 Criminal sanctions can be imposed on various stakeholders, including state officials. Specifically, “those who fail to abide by the prevailing spatial plan and cause a change of spatial function, will be punished with a maximum imprisonment of 3 years and a maximum fine of Rp 500.000.000”.88 A government official who is in charge of issuing permits and issues a permit contradicting a spatial plan, “will be punished with a maximum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximum fine of Rp 500,000,000”.89 Beside criminal sanctions, the official will receive the additional sanction of dishonorable dismissal from his position.90

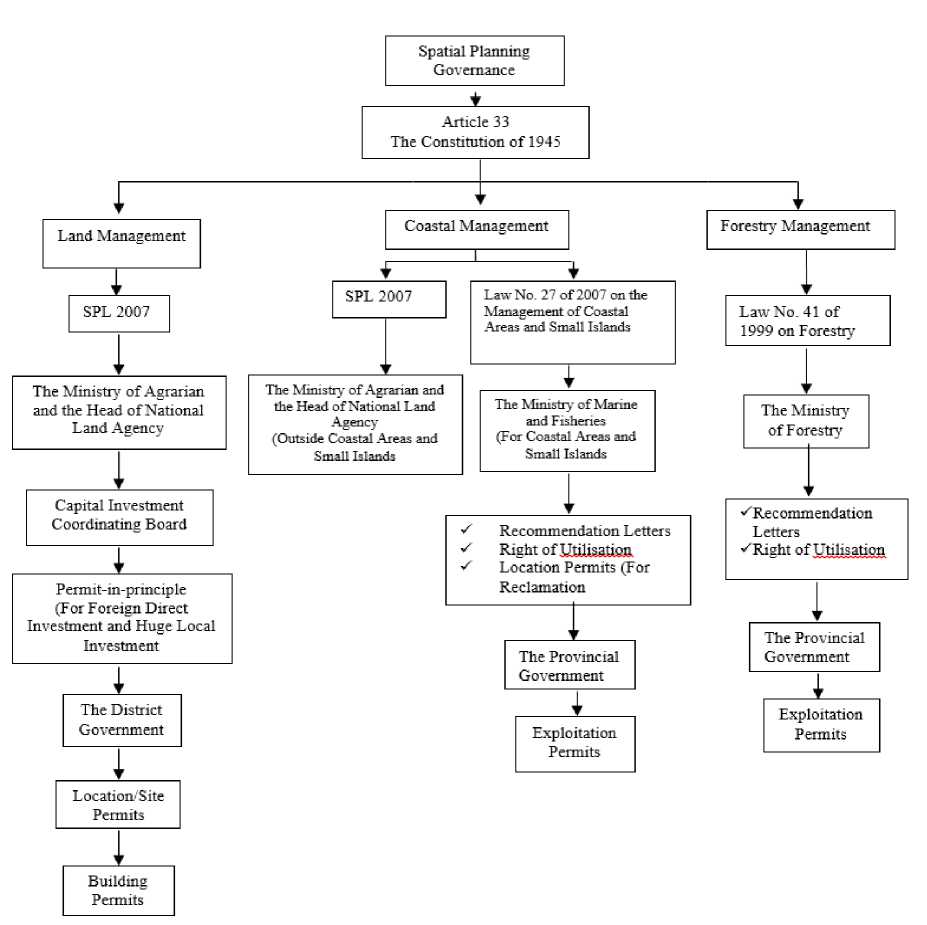

This section explains the involvement of a number of government institutions that have overlapping authority concerning spatial management in Indonesia. At the central government level, three ministries are involved in this: the Ministry of Agrarian and the Head of National Land Agency; the Ministry of Forestry; and the Ministry of Marine and Fisheries. The following diagram shows how spatial management is managed and interrelated in three different ministries in Indonesia.

Diagram 1

The Relationship between Spatial Planning, Forestry, and Coastal Management

Sources: Compiled by the Author

The issuance of SPL 1992 should be the legal basis to integrate spatial management in Indonesia. Specifically, the preamble to this law expressly stated that “the management of many varieties of natural resources and land, sea and air, must be coordinated and integrated by developing a spatial policy…”.91 However, as the above task indicates, the central government has stated that SPL 1992 is only applied to land management, excluding land that was classified as forest by the Ministry of Forestry.92 Likewise, in the mining, oil, and gas sectors, the central government grants exploitation permits to private companies through production sharing contracts.

In consequence, in the Reformation era, the fragmented approach to spatial planning is thriving. The newly enacted SPL 2007 does not apply to forest areas. Instead, the central government has declared Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry as the legal basis for forestry management in Indonesia,93 granting monopolistic authority to the Ministry of Forestry to plan, use, and control forest areas in Indonesia.94 Hence, this ministry has authority to grant a utilization permit in a forest area for tourist development. Likewise, the Ministry of Marine and Fisheries, through the issuance of central government Law No. 27 of 2007 on the Management of Coastal Areas and Small Islands, now has authority to issue the “right of utilization” or Hak Pengusahaan Perairan Pesisir (“HP-3”) in areas that are classified as “coastal areas”.95 The following sections explain these laws in more detail.

Central government Regulation No. 36 of 2010, which implements central government Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry, explains some commercial activities can be undertaken in nature conservation areas,96 including wildlife reserves, national parks, forest parks and nature parks.97 In tourism, for example, there are two types of tourism business recognized by this regulation: ecotourism services and ecotourism facilities.98 As regards ecotourism facilities, these include tourism businesses that provide accommodation and adventure tourism facilities.99 Ecotourism businesses may only be started after obtaining an utilization permit,100 which is only granted in respect of national parks, forest parks and nature parks.101 The utilization permit is granted for 55 years and may be extended for another 20 years.102

The government (that is, a Minister, Governor or Mayor/Regent) will grant a utilization permit subject to the following conditions:

-

a. the permit is not a title of ownership or control over the national park area, forest park, or nature park;

-

b. the permit cannot be used as collateral;

-

c. the permit may only be transferred with the written approval of the Minister, Governor or Regent/Mayor following their respective powers;

-

d. the area permitted for the development of natural tourism facilities shall be, at most, 10 per cent of the total area specified in the permit;

-

e. ecotourism facilities that are built for tourism accommodation shall be semipermanent and their styles shall be in accordance with the local architecture; and

-

f. the development of ecotourism facilities shall follow natural conditions and maintain the existing landscape.103

Central government Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry and its implementing regulations regulate forest management in Indonesia. Forest areas have three important functions, namely conservation, protected function, and production.104 Provincial and district governments must retain forest areas of at least 30 per cent of the total watershed area within provincial and district areas.105 Furthermore, the government must divide forest areas into utilization and protection blocks.106

Central government Regulation No. 28 of 2011 explains the forest utilization plan in nature conservation areas.107 The regulation defines “a nature conservation area” as “a region with certain characteristics, both in land and in waters that have the main function of the protection of life support systems, preservation of the diversity of plant and animal species, and sustainable utilization of natural resources and ecosystems.”108 This area consists of national parks, forest parks and nature parks, that are managed based on zoning and block systems.109 The block system divides the nature conservation area into protection blocks, utilization blocks and other blocks.110

There are other related laws and regulations at the central level that emphasize the importance of coastal areas. Central government Law No. 27 of 2007 on the Management of Coastal Areas and Small Islands defines the “coastal area” as “a transitional area between terrestrial and marine ecosystems that are affected by a change in land and sea”.111 Meanwhile, “coastal waters” are “the sea bordering land covering waters as far as 12 nautical miles measured from shorelines, waters connecting beaches and islands, estuaries, bays, shallow waters, swampy swamps, and lagoons.”112

The right to utilization of coastal waters is given in the form of the “right of cultivation” or HP-3,113 taking into account the sustainability of coastal ecosystems and small islands, indigenous peoples, national interests, and the right of innocent passage

for foreign vessels.114 This right is valid for 20 years115 and can be given to Indonesian citizens, legal entities that are established under Indonesian law, and indigenous peoples.116 The utilization of small islands and adjacent waters is prioritized for one or more of the following interests: conservation; education and training; research and development; marine aquaculture; and tourism.117

Under this Law, the regional government must set limits on coastal borders adapted to topographic, biophysical, coastal hydro-oceanography, economic and cultural needs.118 The determination of coastal borders should take into account: protection against earthquake and tsunami; coastal protection from erosion or abrasion; protection of artificial resources on the coast from storms, floods and other natural disasters; protection of coastal ecosystems, such as wetlands, mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds, sand dunes, estuaries, and deltas; setting public access; and making arrangements for drains and waste.119

The government may regulate how reclamation is to be done in coastal areas and small islands. Reclamation shall be done to increase the benefits and added value of coastal areas and small islands in terms of their technical, environmental and socioeconomic aspects.120 Reclamation should carefully consider: the sustainability of life and livelihood of the community; the balance between the interests of utilization and the interests of environmental preservation of coastal and small islands; and the technical requirements for the collection, dredging and stockpiling of materials.121

There are some important prohibitions on the use of coastal areas and small islands. These include:

-

a. mining coral reefs, which cause damage to coral reef ecosystems;

-

b. mining coral reefs in conservation areas;

-

c. using explosives, toxic materials, and other materials that damage coral reef ecosystems;

-

d. felling mangroves in conservation areas for industrial activities and settlements;

-

e. sand mining that technically, ecologically, socially or culturally damages the environment; and

-

f. undertaking physical development that causes damage to the environment and harms the surrounding community.122

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122 Ibid., art 35.

To sum up, the presence of three different ministries with interrelated authority in managing land, forest and coastal areas in Indonesia reflects how SPL 2007, forestry and coastal laws are directly and indirectly linked.

The idea of “Omnibus Law” is rather peculiar to the typical Indonesia regulationmaking scheme.123 This idea is commonly applied in the common law system but not so common in the civil law country like Indonesia. However, the government claims that this is the best tactic to advance the regulatory context, particularly the level of ease of doing business in Indonesia. This Law is aimed to deregulate the overlapping, scattered, and conflicting laws related with business activities.

The government is right when it states that the number of laws and regulations in Indonesia has touched the phase of hyper-regulation. For instance, there are already 1693 laws, 182 Government Regulations in lieu of laws, 4605 Government Regulations, 2109 Presidential Regulations, and 15971 Regional Regulations.124 This hyperregulation has caused to a decline of Indonesia's competitiveness, making it is less attractive to investors.

The issuance of Job Creation Law has raised a controversy due to its process. The procedure of drafting this Law is undemocratic as it is not transparent and hastily conducted. Furthermore, the target to complete it within 100 days is unrealistic as the content of this Law will significantly change some existing laws in Indonesia, including spatial management. Referring to Myrdal, this kind of law can be qualified as a “sweeping legislation”.

Job Creation Law amends and replaces around 74 laws that are considered as the impediment of job creation and investment in Indonesia. Concerning spatial management, this Law has emerged a big hope that Indonesia will end the fragmented approach to spatial management.125 Article 17-point 2 modified Article 6 the 2007 SPL. Article 6(4) the 2007 SPL now states that “arrangement of the national territory, spatial planning provincial areas, and the arrangement of regional plans regencies are complemented and aimed to avoid overlapping spatial planning arrangements”. Article 6(5) then states that “spatial planning for the national territory includes jurisdiction and national sovereign territory which includes land space, marine space, and space air, including the space within the earth”.126

However, this Law appears to be inconsistent when it says that management of marine and airspace resources regulated by a separate Law.127 Article 6(8) has acknowledged the potential problem on the fragmented approach, but rather than settle it, this Law will issue another government regulation to fix this issue. It states that “in the event of a mismatch between spatial planning related to land use and forest area, it will be

resolved through the issuance of governmental regulation”. The government then issues 4 different regulations to implement Job Creation Law concerning spatial management, including Government Regulation No. 21 of 2021 on Administration of Spatial Planning; Government Regulation No. 23 of 2021 on Forestry Management; Government Regulation No. 25 of 2021 on Energy and Mineral resources; and Government Regulation No. 27 of 2021 on Administration of Marine and Fishery.

As the spatial authority has been planned, delivered and executed by, at least, three different ministerial-level institutions, there is a huge possibility of conflicting and overlapping authorities as shown by old and new order regime. The existence of hierarchy of Law in Indonesia does not resolve this issue.

An understanding of spatial planning regulation in Indonesia requires knowledge of Law No. 12 of 2011 on the Establishment of Legislation. The purpose of this statute is to provide guidance on how to enact legislation, particularly for authorized government institutions at central, provincial and district levels.128 This Law also places all laws into a hierarchical order,129 meaning that lower regulations should be based on, and not contrary to, higher regulations. For example, the contents of provincial and district regulations must not conflict with the 1945 Constitution, Statutes, and Government Regulations.130

However, the vagueness appears in article 8(2) Law No.12 of 2011. It admits the existence of additional types of regulation that do not appear in the hierarchy but may be authorized by higher-level laws or are otherwise enacted under “legitimate authority” – meaning the authority provided by law to execute particular government functions.131 Officials, and public agencies at all levels, can issue binding regulations on this basis. For instance, they may enact ministerial regulations, governor’s regulations, mayor’s regulations, circular letters, directives or guidance, and these can have the same binding effect132, even though they do not appear in the hierarchy. In this context, the more institution or agencies involved, the more possibility of conflicting and overlapping regulations.

There have been critiques of the operation of the hierarchy of laws in Indonesia. Butt and Lindsey, for example, state that Law No. 12 of 2011 has no provisions to explain what type of laws should prevail over others when a contradiction occurs.133 This leads to considerable problems, as Indonesia is notorious for contradictory laws enacted by different agencies and officeholders, making it unclear which law should be followed. 134 For example, consider a presidential regulation and a regional regulation, which

both deal with the borders of a local conservation area in Bali. Law No. 12 of 2011 suggests that the presidential regulation should prevail in the event of any inconsistency. However, if the presidential regulation were enacted under direct delegation from a central government regulation, and the regional regulation is a provincial regulation delegated from a law (statute), would the presidential regulation still triumph?135 Following the hierarchy, it is arguable that the provincial regulation authorized by statute has a higher position than the presidential regulation, which was authorized by a central government regulation.136 Unfortunately, there is no authoritative answer to this problem.

This fact has significant consequences in the context of spatial planning regulation. In the Benoa Bay Reclamation Project, there was a contradiction between presidential regulations and provincial regulations regarding the status of Benoa Bay, leading to controversy over the planning of massive tourism projects in this area.

Lex specialis derogat lex generalis explains that if two contradictory laws occur, the more specific of the two revokes the broader law. Another is lex posteriori derogat lex priori, meaning that if two laws contradict each other, then the more recently-promulgated law triumphs.137 However, these two principles are not consistently applied, and they appear to function only to assist in resolving disputes over laws that come from the national legislature. It is vague whether these principles can be implemented to settle contradictions between laws enacted by other agencies or levels of government. If, for instance, different ministries enact conflicting laws, could the later revoke the previous one? Would the more specific of the two triumphs?138 Again, there is no authoritative answer to this issue. As Fuller has said, this may end up with the regulatory failure of spatial management in Indonesia.

The insistence to employ fragmented approach to spatial management has linked to oligarchy issue as shown by previous administration. In old order, by having the Basic Agrarian Law No. 5 of 1960, Soekarno had the chance to use this law to integrate spatial management in Indonesia, but never did so. Instead, Soekarno chosen different ministers to handle different natural resources, such as gas, oil, mining, and forestry sectors.139

In Soeharto administration, he was unwilling to integrate spatial arrangements, as the exploitation of natural resources through this approach had been the central government's main source of income. As mentioned, if spatial management was integrated, the central government would be required to renegotiate existing production contract sharing agreements in mining, gas and oil, and existing concessions in forestry management, and this would adversely affect the public-private business network, the backbone of the Soeharto administration. This practice is thriving when SPL 2007 applies to land-use, Law No. 41 of 1999 applies to forestry, and Law No. 27 of 2007 applies to coastal areas.

In the Reclamation Project, the involvement of powerful investors associated with national-level political leaders in Indonesia may explain why the government keep separating spatial management into different authorities under different ministries. When this kind of investors had provided major financial supporters in a presidential campaign, they would be granted a right of cultivation in land use, coastal areas or production-sharing contract in mineral and gas as a reciprocal benefit.140 This kind of pattern would not be possible if spatial management is integrated under one particular authority and institution.

In the regional government era, this kind of practice has spanned local governance. Local elections require huge sums of campaign money. Governors and Regents are motivated to collect money to prepare for future elections from particular investors. Becoming a Governor or a Regent in the current era of direct elections is extremely expensive. One candidate for Regent spent around IDR 10 billion (USD 1 million) just to campaign in a local election in a medium-sized district. In gubernatorial elections, a candidate must spend IDR 100 billion (USD 10 million) to realistically win the election.141 This cost consists of the nomination of a candidate to participate in the elections; and the involvement of strategic advisors, political consultants, opinion surveys and media campaigns.142 Interestingly, the costs also cover what it is called as “vote-buying”: illegal distribution of cash payment to voters.143

As this cost is extremely expensive, this kind of candidate often collected fund from an individual or group that financially committed to be major supporters. As a reward, if this candidate won the election, they would be granted spatial planning permit or right of cultivation in particular areas, zones or blocks, taking advantage on the fragmented authorities in the era of regional autonomy.

The fragmented approach to spatial management has been practiced since the independence of Indonesia? Historically, the government of Indonesia acknowledged the importance of integrated management on spatial planning. This issue has been regulated in Basic Agrarian Law No. 5 of 1960, SPL 1992 and SPL 2007. The newly controversial Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation has emerged a big hope that Indonesia will end the fragmented approach to spatial management. It does explain spatial planning for the national territory includes jurisdiction and national sovereign territory which includes land space, marine space, and space air, including the space within the earth. In reality, however, there is a significant gap between the law “on the books” and the law in action as the fragmented approach to spatial planning is

thriving. Land-use planning is regulated under Spatial Planning Law under the authority of Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning. Ministry of Forestry under Forestry Law is granted monopolistic authority to the Ministry of Forestry to plan, use, and control forest areas in Indonesia. In coastal area, there is Law No. 27 of 2007 on the Management of Coastal Areas and Small Islands, and the Ministry of Marine and Fishery has the authority to grant the right of cultivation over coastal areas. In the mining, oil, and gas sectors, the government grants exploitation permits to private companies through production sharing contracts. This fragmented approach has adverse consequences as it leads to overlapping authorities that may end up with disharmony and conflicting regulations. Moreover, the existence of hierarchy of Law in Indonesia does not resolve this issue. Besides, the insistence to employ fragmented approach to spatial management has linked to oligarchy issue as shown by old and new order. In the regional autonomy era, this kind of practice has spanned local governance.

References

Books

Baker, J. (2012). The Rise of Polri: Democratisation and the Political Economy of Security in Indonesia.London School of Economics and Political Science.

Butt, S. and Lindsey,T. (2018). Indonesian Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Fuller, L. (1969). The Morality of Law. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2nd revised ed.

Myrdal, G (1970). The Challenge of World Poverty: A World Anti-Poverty Programme in Outline. Penguin Books.

Morgan, B. and Yeung, K (2017). An Introduction to Law and Regulation: Text and Materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moeliono, T.P. (2011). Spatial Management in Indonesia: From Planning to Implementation, Cases from West Java and Bandung, A Socio-Legal Study. Universiteit Leiden

Nordholt,H.S. and Klinken,G.V. (eds).(2007). Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in post-Soeharto Indonesia. Leiden: KITLV Press

Colombijn, F. et al (eds).(2005). Kota Lama Kota Baru, Sejarah Kota-Kota di Indonesia. Jakarta: Penerbit Ombak.

Sampe, S. (2015). Political Parties and Voter Mobilisation in Local Government Elections in Indonesia: the Case of Manado City. the University of Canberra.

Silas, J. (1989). Perjalanan Panjang Perumahan di Indonesia dalam dan Sekitar Abad XX. The Institute of Technology Bandung.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2015). Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development. Geneva: United Nations.

Journals

Allmendinger, P. and Haughton, G. (2013). The Evolution and Trajectories of Neoliberal Spatial Governance: Neoliberal Episodes. Planning, Practice and Research, 28(1), 6-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.699223.

Aspinall, E. et al (2017). Vote Buying in Indonesia: Candidate Strategies, Market Logic and Effectiveness. Journal of East Asian Studies 17, 1-27, DOI:10.1017/jea.2016.31

Aspinall, E., and Mas’udi, W. (2017). The 2017 Pilkada (Local Elections) in Indonesia: Clientelism, Programmatic Politics and Social Networks. Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 3(3), 417-426,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44684048

Albrechts,L. (2006). Shifts in Strategic Spatial Planning? Some Evidence from Europe and Australia. Environment and Planning, 38(6), 1149-1170, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1068/a37304

Berenschot, W. (2018). The Political Economy of Clientelism: A Comparative Study of Indonesia’s Patronage Democracy. Comparative Political Studies 51(12), 1563-1593, https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018758756

Healey, P. (1998). Collaborative Planning in a Stakeholder Society. The Town Planning Review, 69(1), 1-21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40113774

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(98)00028-6

Hudalah, D. and Woltjer, J. (2007). Spatial Planning System in Transitional Indonesia.

International Planning Studies, 12(3),291-303.DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470701640176

https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230010406

Otto,J.M. and Syafrudin, S. (1990). Hukum Tata Ruang di Indonesia dan Belanda. Pro Justitia, 8(2), 5-28.

Scott,A.J. et al. (2013). Disintegrated Development at the Rural–Urban Fringe: Reconnecting Spatial Planning Theory and Practice. Progress in Planning, 83, 1-52 DOI: 10.1016/j.progress.2012.09.001

Taylor, N. (2010). What Is This Thing Called Spatial Planning? An Analysis of the British Government's View. The Town Planning Review, 81(2), 193-208. DOI: 10.3828/tpr.2009.26.

Valk, A.V.D. (2002). The Dutch Planning Experience. Landscape and Urban Planning, 58(2-4), 201-210, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-2046(01)00221-3

Wekwete, K.H. (1995). Planning Law in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Focus on the Experiences in Southern and Eastern Africa. Habitat International, 19(1) 13-28.

Wei-Ju, H. and Maldonado, A.M.F. (2016). High-tech Development and Spatial Planning: Comparing the Netherlands and Taiwan from an Institutional Perspective. European Planning Studies , 24(9), 1662-1683.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1187717

Online

Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Renville Agreement.

Available From https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/historical-

documents/Pages/volume-13/22-renville-agreement.aspx (Accessed on 17 January 2021).

Bali Mangrove Bay is Now a Conservation Zone, Nixing Reclamation Plan, Mongabay, 11 October 2019, available from https://news.mongabay.com/2019/10/bali-benoa-bay-mangroves-conservation-reclamation/ (Acessed on 17 February 2021).

Dili tycoon deal triggers alarm, the Sidney Morning Herald, 3 May 2009. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/world/dili-tycoon-deal-triggers-alarm-

20090502-aqtj.html (Accessed on 23 February 2021).

Deborah Cassrels, The businessman who aims to turn Bali into the new Palm Islands, Financial Review, 9 September 2016. Available from

https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/anguish-bali-tourist-development--and-the-enigmatic-tomy-winata-20160829-gr3v4r (Accessed on 17 February 2021).

Laws and Regulations

Undang-Undang No. 5 Tahun 1960 tentang Peraturan Dasar Pokok-Pokok Agraria

Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 24 Tahun 1992 Tentang Penataan Ruang.

Undang-Undang Nomor 26 Tahun 2007 Tentang Penataan Ruang.

Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 41 Tahun 1999 Tentang Kehutanan.

Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 27 Tahun 2007 Tentang Pengelolaan Wilayah Pesisir dan Pulau-Pulau Kecil.

Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 Tahun 2011 Tentang Pembentukan Peraturan Perundang-Undangan

Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 36 tahun 2010 tentang Pengusahaan Pariwisata Alam di Suaka Margasatwa, Taman Nasional, Taman Hutan Raya, dan Taman Wisata Alam.

Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 28 Tahun 2011 Tentang Pengelolaan Kawasan Suaka Alam dan Kawasan Pelestarian Alam.

Keputusan Menteri Kelautan dan Perikanan Republik Indonesia No. 46/kepmen-kp/2019 tentang Kawasan Konservasi Maritim Teluk Benoa di Perairan Provinsi Bali.

Court Decision

Keputusan Mahkamah Konstitusi No 137/PUU-XIII/2015.

Jurnal Kertha Patrika, Vol. 43, No. 2 Agustus 2021, h. 145-166

166

Discussion and feedback