Implication of Zoning Regulation on Environmental Protection and Land Rights After Enactment of Job Creation Law

on

Implication of Zoning Regulation on Environmental Protection and Land Rights After Enactment of Job Creation Law

Luh Putu Yeyen Karista Putri1

1Fakultas Hukum Universitas Pendidikan Nasional, E-mail : yeyenkarista@undiknas.ac.id

Article Info

Received: 8th April 2022

Accepted: 23rd May 2023

Published: 27th May 2023

Keywords:

Zoning Regulation, Environment Protection, Land

Rights

Corresponding Author :

Luh Putu Yeyen Karista Putri, E-mail :

DOI:

10.24843/JMHU.2023.v12.i0

1.p02

Abstract

Job Creation Law, which was re-enacted in 2023, amended 78 Acts in Indonesia simultaneously, including the Spatial Planning Act. The law requires all local authorities to enact detailed plan (RDTR) supplemented with zoning regulation. The statutory approach is used to analyze available options to harness zoning regulation as an instrument for environmental protection. A case study on RDTR and zoning regulation of the South Kuta subdistrict was conducted to examine the impact of RDTR on the land right and outline constraints that may hamper RDTR drafting and implementation. The results show that zoning regulation can be an ultimate tool for environmental protection, provided several conditions are met. First, local authorities must reserve existing forests and, even better, allocate additional green areas. Secondly, the central government must provide a comprehensive manual, advise and supervise local authorities to ensure favorable zoning regulations for the environment. On the other hand, zoning regulations must be updated to accommodate development needs and support the small-scale business by providing alternatives for mixed-land use. Local authorities must consider the area's characteristics, including economic and socio-cultural factors, and apply objective (science-based criteria) to determine the zoning while improving staff expertise, outsourcing professional advice, and allowing public participation. It is critical to oversee the zoning-making process all over Indonesia because once enacted; it will be applicable for 20 years under rigorous requirements for alteration.

public consultations. Finally, in March 2023, the government regulation in lieu was reenacted as Law No. 6 of 2023. This thematic law aims to create employment by improving the investment climate and harmonizing laws related to business licensing in several sectors, both at the national and local levels (Chapter III). In addition, the Job Creation law provides labor regulations in Chapter IV and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Chapter V.

Job Creation law of 2023 simultaneously amended 78 Acts in Indonesia, including the Spatial Planning Law No 26 of 2007. This Law is the second spatial planning act in Indonesia that replaces the Spatial Planning Law No. 24 of 1992. Unlike the previous act, the new law explicitly divides authority regarding spatial planning at national, provincial, district, and municipality levels and sanctions. Thirty-seven provisions of the Spatial Planning Law are amended under Article 17 of the Job Creation Law. Job Creation Law requires all local authorities to enact detailed spatial planning (Rencana Detail Tata Ruang or RDTR) supplemented with zoning regulation.1 However, only 55 out of 2000 local authorities have enacted RDTR and zoning regulations.2 It is vital to oversee the formation of RDTR and zoning regulations all over Indonesia to ensure development needs in each region without neglecting environmental protection.

Environmental issues such as global warming, climate change, and deforestation have often been raised in mainstream media.3 Indonesian forests have outstanding universal value due to their size and astounding diversity of ecosystems.4 Although there are several laws and regulations regarding the environment in Indonesia, the impact of environmental degradation is becoming more evident. Besides disturbing the balance of the surrounding ecosystem, environmental degradation also affects environment carrying capacities, such as clean air and water availability and soil fertility.5 In addition, climate change also has several irreversible negative impacts, including a) the shift of wet and dry months, which causes crop failure and contributes to food supply shortages;6 b) threat to biodiversity, including endangered species; c) health problems, plants, and livestock disease outbreak; 7 d) vulnerability to natural disasters such as

heatwaves, droughts, forest fires, landslides, floods, and tropical storms.8 Furthermore, some researchers suggest a complex linkage between climate change and multiple forms of conflicts that sometimes lead to social instability.9 Therefore, immediate action is needed to tackle the threat to human security and societal stability.10

Zoning regulation is a spatial planning instrument used to divide the area into zones and determine what activities can be carried out. 11 Besides promoting desirable development patterns, RDTR and zoning regulation can be used as an environmental protection instrument by establishing existing forests as protected areas to halt deforestation. Forest conservation is critical to overcoming climate change and biodiversity loss.12 RDTR and zoning regulations are integrated into the online licensing system, and therefore, the system will automatically reject license applications within conserved areas. Under Article 13 (a) and Article 14 (5) of Job Creation Law, conformity of business activity with zoning regulation is the first requirement that must be satisfied in order to apply for business licensing through the online-single submission (OSS) system.

The preparation of RDTR and zoning regulation all over Indonesia must involve public participation because once established, it will be valid for 20 years under rigorous requirements for alteration.13 On the other hand, RDTR and zoning regulations must accommodate development interests without neglecting the land rights of the surrounding community. The first area with RDTR and zoning regulations in Bali is South Kuta District in Badung Regency. 14 Some landowners complain about the applicable zoning regulation, which adversely affects land pricing. This research aims to analyze further the implications of RDTR and zoning regulations on land rights and the obstacles found in the drafting process and its implementation.

There are several previous studies concerning zoning.15 discussed zoning from the law and economic perspective by analyzing the effect of zoning on land price using the Coase theorem. 16 Matey (2016) suggested that zoning can affect land values because it interferes with the operation of the property market and limits the amount of land

available for residential uses.17 Djunaedi et.al. provided comparative study on zoning implementation in the United States and Singapore.18 This research uses materials from previous studies to elucidate the alternative role of zoning as an instrument for environmental protection, the impact of zoning on the enjoyment of land rights, and constraint in drafting and implementation of zoning. The discussion will be adjusted to massive law and licensing reform in Indonesia.

This research uses the statutory approach by examining regulations and legislations related to RDTR, zoning, and the environment. In addition, law and economic theory are also employed to analyze the rationale behind zoning and how it can be harnessed as an instrument for environmental protection. Meanwhile, the case study assesses how RDTR and zoning regulation affect land rights in South Kuta Sub-District. This study uses primary legal materials, namely legislation, and secondary legal materials derived from academic literature, books, articles, and available resources such as data available on the Indonesia Land Agency's official website. The data collection technique used in this research is the literature study. The data are analyzed using the descriptive technique to produce a general conclusion and recommendation.

-

3. Result and Discussion

-

3.1 Zoning Regulation as an Environment Protection Instrument

-

3.1.1 History and Development of Zoning

-

-

Zoning is a land-use instrument undertaken by local government which divides jurisdiction into zones and prescribes what may be done in each zone.19 The various land-use designated by zoning regulations are residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural.20 Furthermore, zoning comprises constraints on land development. Most frequently observed restrictions include minimum area per lot, the maximum height of the buildings, and minimum setbacks for a building from its neighbors and the street.21 The concept of zoning was developed in the early 20th century in response to industrialization, population growth, and the increasing number of private nuisance claims. In the landmark case of Rex v. White and Ward, the English royal government took action against the owners of a Sulphur factory that caused a smell regarded as a public nuisance. Land-use control was the government's attempt to prevent public nuisances rather than provide mitigation after the nuisance is committed.22

The rationale for zoning is to overcome externalities, namely spillover effects on neighbors caused by certain activities, such as factories or industries, by employing police-power regulations to separate uses.23 New York was credited as the first city that enacted a comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1916, which developed robustly. Zoning regulations are ubiquitous in the United States and cities worldwide. Houston, Texas, is the only city in the United States that employs private covenants instead of zoning. Private covenants are often adopted by private residential governments, such as homeowner associations, even when zoning is available. Private covenants can prohibit activities that zoning permits, but covenants cannot permit owners to undertake activities that zoning prohibits. 24 Another alternative for zoning is a discretionary system. While in the regulatory system, the implementation of land use planning is based on legal certainty in the form of zoning, in the discretionary system, the decision is made towards a request for land use based on planning authority consideration.25

Zoning is part of the government’s police power to make regulations. Since the prevalence of zoning, its scope has been expanded to meet the needs of suburban and rural communities. Initially, zoning aims to ensure land use compatibility and protect public health, safety, and general welfare. However, such purpose has expanded since the adoption of early zoning ordinances.26 Some municipalities make zoning to ensure that land is put to its highest and best use, including conserving natural resources such as water quality and wildlife habitats.27

In the United States, zoning is purely decentralized, and the authority is granted to municipalities.28 Meanwhile, Indonesia has a more complex spatial planning regime that is significantly influenced by the characteristic of the unitary State with the decentralization system, geographical condition of the archipelagic State, and sociocultural factors. Prior 2007, Indonesia did not recognize zoning as a land-use instrument. At that time, spatial planning was regulated under Law No. 24 of 1992. The spatial planning system back then was simpler where the central government’s role are more dominant than the local authorities. Only after the government enacted Law No 26 of 2007 that Indonesia recognize zoning as an integral part of spatial planning regime. The current regime of the spatial planning system in Indonesia can be seen in figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Spatial Planning Regime in Indonesia Source: Article 14 Spatial Planning Law

As provided in figure 3.1, Indonesia’s spatial planning regime consists of general and detailed spatial planning. The spatial planning regulations are arranged in hierarchical order. Thus, the Spatial Planning at the regency/municipality level (RTRW Kab/Kota) should be based on Spatial Planning at the Provincial (RTRWP) and National level (RTRWN) which is stipulated under the provision of Article 6 paragraph (3) of the Law of Republic of Indonesia No. 26 of 2007 concerning Spatial Planning Law (hereinafter Spatial Planning Law). Furthermore, those regulations should complement each other to avoid overlapping regulations as stipulated under the Spatial Planning Law.The complex regime often confuses the public in distinguishing several spatial planning regulations. The comparison of several spatial planning regulations can be seen in table 3.2.

Table 3.1 Comparation of RTRWN, RTRWP, RTRWKab/Kota, and RDTR Kab/Kota

|

No |

Instrument Type |

Authority |

Content |

Scale |

|

1 |

RTRWN |

Ministry |

objective, policy & strategy, spatial structure & pattern planning establishment of strategic area, directions for spatial use & five-year medium-term program, incentive, disincentive and sanction |

1:1.000.000 |

|

2 |

RTRWP |

Province |

objective, policy & strategy, spatial structure & pattern planning, directions for spatial use & five-year |

1:250.000 |

|

medium-term program, incentive, disincentive and sanction | ||||

|

3 |

RTRWKab |

Regency |

objective, policy & strategy, spatial structure & pattern planning, directions for spatial use & five-year medium-term program, incentive, disincentive and sanction |

1:50.000 |

|

RTRWKota |

Municipality |

objective, policy & strategy spatial structure & pattern planning directions for spatial use & five-year medium-term program, incentive, disincentive and sanction |

1:25.000 | |

|

4 |

RDTR Kab/Kota |

Regency Municipality |

objective, spatial structure & pattern planning, directions for spatial use and zoning regulation |

1:5.000 |

Overall, the contents of spatial planning regulations are similar except for the RDTR, which provides zoning regulations. Depending on the area and scale required, each regency/municipality can have more than one RDTR.(Article 21 Ministry of ATRBPN Regulation No. 11 of 2021 Concerning Procedures for the Preparation, Review, Revision, and Issuance of Substantial Approval of Spatial Planning Regulations,) The preponderant part of spatial planning regulation is spatial structure and pattern planning. The spatial structure consists of the development of residential areas, public services, transportation, and infrastructure, while the spatial pattern consists of the conservation zone and cultivation zone.(Article 1 (3) and (4) Spatial Planning Law; Article 28 (2) and (3) Ministry of ATRBPN Regulation No. 11 of 2021 Concerning Procedures for the Preparation, Review, Revision, and Issuance of Substantial Approval of Spatial Planning Regulations, n.d.) The main differences among the regulations are the scope of application and the scale required. All spatial planning regulations are applicable for 20 years and subject to 5 years of periodical review.29

The environmental aspect has become a prominent part of spatial planning, particularly in determining spatial patterns and allocation of conservation zone. Before the Job Creation Law, spatial planning regulations must allocate at least 30% of the watershed as a forest area. This provision is amended, and thus limitation for minimum forest area no longer exists. Job Creation Law amends the minimum requirement of 30% of the watershed as forest area stipulated in Article 17 (5) Spatial Planning Law and Article 18 (2) Forestry Law. Nevertheless, RDTR and zoning regulations can be harnessed as an instrument for environmental protection by reserving the existing forest as a conservation area and allocating additional areas as protected forests. RDTR and zoning regulations will be made publicly available through the government's official website using Geospatial Information System (GIS). The digital spatial planning map, including RDTR and zoning regulations, can be accessed through the official website of the Ministry of ATRBPN (https://gistaru.atrbpn.go.id). Geospatial Information Agency (Badan Informasi Geospatial) is assigned to optimize the dissemination of geospatial information to the public.

In addition, RDTR will be integrated into the online licensing system. Indonesia has implemented an integrated licensing system known as Online Single Submission (OSS) since 2018. OSS is a breakthrough in Indonesia’s licensing history because it aims to promote ease in business licensing applications. The system was updated several times, and the latest version of OSS is adjusted based on Job Creation Law. According to Article 13 of Job Creation Law, the first step in business licensing application is the compatibility of types of business activity and location with the zoning regulation. If the business activities and location are compatible with the zoning regulation, the system will automatically issue an approval for spatial use and vice versa.30 Establishing conservation areas based on RDTR will halt deforestation because the system will automatically reject license applications for business activities or any development within the conservation area.31

RDTR and zoning are enacted by local authorities at the regency/municipality levels.32 Hence, the onus to establish a conservation zone is at the regency/municipality level. There are 514 regencies and municipalities in Indonesia with diversity in terms of geographical condition, socio-cultural factors, and level of development.33 However, the central government can ensure maximum protection of forest area in each regency/municipality by establishing explicit requirements in the manual for spatial planning drafting. RDTR and zoning are placed in the lowest hierarchical order and complement RTRW at the National, Provincial, and Regency/Municipal levels.34 It is vital if spatial planning regulations at all levels prioritize conservation zone establishment because RDTR and zoning regulations will be adjusted accordingly. Substantial approval from the central government is required before RDTR and zoning can be enacted. 35 Hence, the central government can supervise conservation area allocation in each regency/municipality by granting substantial approval only to the RDTR and zoning draft, which provides optimum allocation for conservation zone.

The development of land law was built since feudal reform in 1066.36 The definition of land encompasses both tangible, physical property (fields, factories, houses, shops, and soil) and intangible rights in the land (the right to walk across a neighbor’s driveway, a mortgage, a restrictive covenant, or the right to take something from another’s land).37 Propriety rights over land can be classified into the estate in land and interest in land. Theoretically, all land in England and Wales is owned by the Crown people may own an estate in the land rather than the land itself. The two most common estate forms in

the land are the freehold estate (the fee simple) and the leasehold estate. Both freehold and leasehold estate comprise the right to use and enjoy the land, but the right of leasehold is limited to a defined period, while the freehold lasts for a lifetime duration.38 The colonial powers influenced Indonesia's land law, particularly the Dutch colonial ruler. Prior to independence, there was dualism of law, which western law applicable to European and Adat law applicable to indigenous people. 39 Fifteen years after independence, Indonesia enacted Basic Agrarian Law (BAL) which is still applicable today. BAL is based on Indonesian traditional (adat) law as long as it does not violate national interests. As the England Law, all land in Indonesia, to the highest degree, is controlled by the State, granting the state exclusive authority to regulate land use and land rights.40 BAL stipulates several types of land rights namely right of ownership (freehold), right of exploitation, right of use, right of building, right of lease, right of opening up land, and right of collecting forest products.41 BAL provides exclusion of foreigners from land ownership to protect the indigenous Indonesian citizens from economically more robust groups.42 In the United States, people can easily purchase a piece of land regardless of their nationality.43 While in Indonesia, a foreigner can only enjoy a right of the lease.44 However, in practice, foreigners can have ownership over land indirectly through third parties such as individual Indonesian (known as nominees, deemed illegal) or an Indonesian company. Another option is to lease the land for a very long period since BAL does not provide a limitation on lease duration.

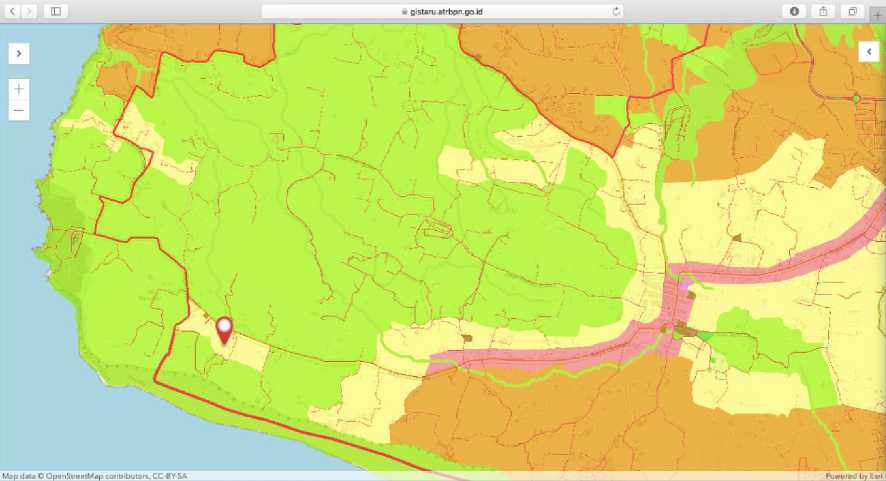

The enjoyment of land rights, even the right to ownership which is the most substantial right to land, are subject to particular limitations.45 The enjoyment of land rights must not negatively impact the community.46 In addition, state has exclusive authority to regulate land use planning through zoning. Zoning is a legal restriction imposed on the enjoyment of land rights. Consequently, individual landowners cannot use their lands except by following the scheme provided in zoning. These are the most common complaints of landowners around Pecatu village since Badung Regency enacted RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-District 2018-2038, as provided in figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-District 2018-2038

South Kuta Sub-district consists of 6 villages that rely primarily on tourism.47 One of the villages in the South Kuta Sub-district is Pecatu village. Pecatu is known for its waves, beaches, and Uluwatu temple. South Kuta Sub-district is the first area with zoning regulation in Bali. Fourteen allowed land use, namely residential, trade, services, offices, education, health, religious, socio-cultural, sports, recreation, arts, tourism, industry, green open space, agriculture and fishery, and infrastructure facilities.48

As shown in Figure 3.1, most of the Pecatu area is marked green, which means that agriculture is the only allowed activity in that area. Even though agricultural land can be built for agritourism facilities, the Floor Area Ration (FAR) should not exceed 0,1, which is highly restrictive. Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is the ratio of a building's total floor area (gross floor area) to the size of the piece of land upon which it is built. See also Article 89 RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-District. Furthermore, Article 89 (4) of RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-district explicitly prohibits agricultural land used for accommodation, trade in goods, or services. Many landowners in Pecatu use the land for non-agricultural purposes such as dwelling, tourism accommodation, and restaurants. The soil characteristic dominated by limestone, difficult access for irrigation, and certain types of plant diseases made the local

community leave agriculture and move to the lucrative tourism sector. A low level of awareness and uncertain control mechanism contribute to the indifference of the local community concerning zoning regulation.

As in any other part of the world, the pandemic has adversely affected the community in Pecatu. Some people go back to the agriculture or farming sector, while others consider selling or leasing their land. The problem that most landowners encounter is the low valuation of their land. It is generally agreed that zoning can affect land values because it limits the land available for residential uses.49 In this case, the low price is caused by the inability to build on land in the agricultural zone. Prospective buyers or tenants will conduct due diligence before purchasing/renting land. Selective buyers will never buy land without a permit, or they will demand a lower price. Because everything is forbidden, some landowners tried to lobby for altering the zoning or getting exceptions that undermine the rule of law. Even the original landowners who have the right of ownership cannot build houses or anything on their land. Due to zoning regulations, some landowners took risks to build illegally on their land without a permit. So far, there is no enforcement mechanism carried out by the authority. Nevertheless, the zoning regulation's detrimental effect still affects the valuation of a building in the case of a mortgage. Some banks even explicitly required building permits for mortgage administration.

Figure 3.3 Allocation of Agricultural Land in Pecatu Village

Allocation for agricultural land in Pecatu village is disproportionate. As shown in figure 3.2, more than 70% of the Pecatu area is allocated for agricultural purposes. The proportion neglects the local community's interests, such as the need for residential areas and the development of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Every business entity in Indonesia, including MSMEs, should apply for business licensing through the online licensing system. Start-ups frequently start as a home-based business. Zoning

exempts home-based businesses from getting a license because the land is in the agricultural zone. Everything is forbidden except that which is expressly allowed in the zoning code. Zoning limits the development of new businesses models in Pecatu. The entrepreneurs have two alternatives: relocating or continuing the business without a license. In some cases, entrepreneurs rent a place (so-called virtual office) compatible with the zoning regulation merely for business application purposes while the actual business activity is in another location. It is ironic for landowners in Pecatu who have vast land and good opportunity but have to rent another place only because of zoning. Article 64 of RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-district justifies zoning in Pecatu. In order to maintain the holiness of the Sad Khayangan temple, land use of the surrounding land is restricted. Sad Khayangan temples are the six main temples in Bali. Uluwatu temple, as one of Sad Khayangan temples, is located in Pecatu village, and therefore, the land use is restricted. As suggested by Fischel, a complex spectrum of overlapping privileges, including traditional and religious law, impedes the development of rural areas.50

As provided in figure 3.2, some areas are marked yellow and orange among the green area. Yellow represents the residential zone, while orange represents the tourism zone. Some landowners in Pecatu complain about the odd pattern of the zoning where the adjacent land is established as a tourism or residential zone. Some landowners consider the zoning unfair and arbitrary because big resorts and hotels can get permits while local owners are hindered by zoning. The justification can be found in Article 62 (d) of RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-district, which stipulates zoning does not affect the pre-existing land use with permits. New zoning regulations are typical to 'grandfather' nonconforming, pre-existing uses rather than require them to discontinue unless they are overly noxious.51

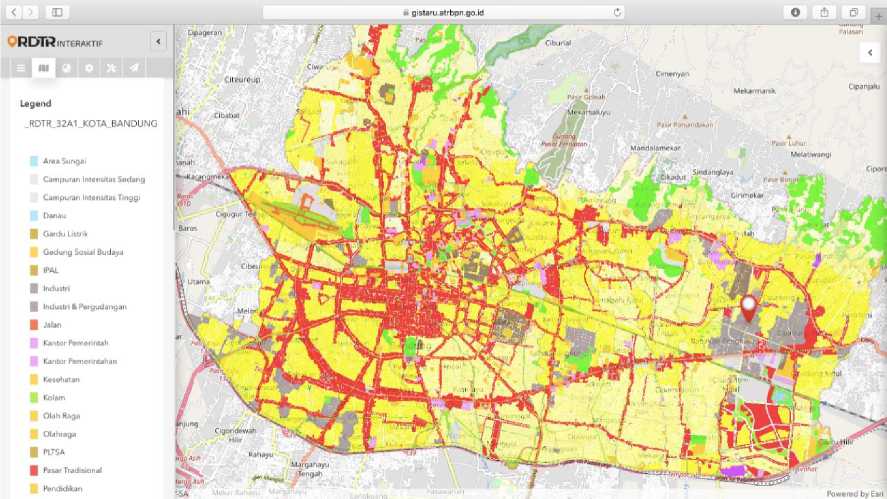

Overall, zoning regulation has adverse effects on land prices and MSME development. Furthermore, the goal of zoning to preserve agricultural areas is far from successful since low awareness, and adherence to zoning makes the local community build without permits on agricultural land. Zoning needs to be updated to the current development need by allowing mix-land use. Bandung Municipality has implemented this approach in its zoning regulation.

Figure 3.4 RDTR and Zoning Regulation of Bandung Municipality 2015-2030

As can be seen in figure 3.3, Bandung establish mix zone indicated with gray in which both residentials and business can be carried out.52 The origin of zoning was built on the urgency to separate residential from commercial areas. However, the home-based business may have added more value to the location than it subtracted from the homeowners' value. There is nothing necessarily inefficient in this process. In other words, the mixed land use maximizes the area’s land value as a whole.53 Zoning must address most actual dangers to public health and stop picayune regulation. Furthermore, zoning must create certainty, predictability, freedom for entrepreneurship, job creation, and small businesses.

Locating zoning at the regency or municipal level leads to the question of who controls the politics. The leading theory suggests several answers (a) the median voter; (b) the bureaucracy, including the planning profession; (c) interest groups, including developers, real estate interests, and NGOs; (d) higher levels of government, such as state legislator. There are no widely accepted answers because the size (both area and population) of the municipality makes a difference in which answer is relevant.54

Since the authority to enact zoning is embedded in the local authority, it is essential to analyze what local authorities are and whose interests they serve. Indonesia's local authorities consist of the regent/ the major and Regional People's Representative

Assembly (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah or DPRD).55 Both regent/major and DPRD members are elected through the public election. Candidate of DPRD member must be nominated by a political party, while regent/major candidate need not be nominated by a political party (independent). According to Article 94 of Local Authority Law, a candidate for a DPRD member must be nominated by a political party. Prior to 2007, the exact requirement applies to a candidate for major/regent, but the Constitutional Court Decision No. 5 /PUU-V/2007 revoke such requirement. Regents or majors served for five years with the possibility of re-election for another five years.56 Meanwhile, DPRD members served for five years with an unlimited possibility for re-election.57

Theoretically, elected major, regent, and DPRD members shall serve constituent interests: the people who vote for them. However, in reality, low political education levels and awareness create indifference, contributing to the underrepresentation of constituent interests. Outside forces such as the nominating political party, developers, and NGOs also can affect the output of zoning. Influential investors, developers, or corporations can hijack the zoning regulation to secure their private interests. Similarly, NGOs also can shape zoning through massive movement. There is very little attention directed toward RDTR and zoning. Hence, it is vital to raise awareness so that the public can involve in the preparation and implementation of zoning.

Competition among regencies/municipalities also can affect zoning regulation. Regents or majors aim to develop their area by providing commercial and industrial property. In order to allure more investors and developers, some local authorities may relax the environmental standards. Such competition creates a “race to the bottom” in environmental quality. Another issue is when the local authorities behave strategically by zoning unlovely uses such as landfills or sewage plants on the border area. This 'beggar thy neighbor' policy also reduces the quality of the regional environment.58

Higher-level government shall undertake several measures to ensure the quality of zoning regulation. Ministry of ATRBPN Regulation No. 11 of 2021 provides extensive rules on procedures for preparing, reviewing, revising, and issuing substantial approval of spatial planning regulations. Under Article 29 of the regulation, a strategical environmental analysis must be integrated to make RDTR and zoning regulations. The regulation also provides a manual on RDTR drafting in Appendix IV. However, the appendixes are not publicly available. In addition, the regulation also lacks a bestpractice compilation. It will be beneficial if the regulation provides an example of mixed-land use as applied by the Bandung municipality. Mixed-land use can accommodate needs for development and support small-scale businesses. Most importantly, the regulation must set a benchmark for preserving the existing forest areas by establishing conservation zones. However, the regulation requires cross-sectoral discussion that

includes the integration of forest delineation during substantial approval. 59 Nevertheless, no provision requires the establishment of conservation areas.

-

3.3.2 Discrepancy of Expertise and Resource

Indonesia has 514 regencies and municipalities with diverse geographical conditions, socio-cultural factors, and levels of development. 60 Even though the implementing regulation provides zoning drafting procedures, the level of expertise will significantly affect the result. Each regency/municipality has a specific department that deals with spatial planning. Usually, the spatial planning department is merged with the public works department. The number and expertise of staff vary in each regency/municipality. The local authorities can hire experts and professionals to ensure the quality of zoning. However, not all local authorities can afford to hire experts due to a lack of resources. Furthermore, the pandemic has caused budget re-allocation in which prioritizing Covid-19 mitigation. The central government is obliged to provide education, training, and technical assistance concerning the preparation of spatial planning regulations.61 The questions is: how far will the central government advise every local authority in Indonesia? Furthermore, RDTR drafting and enacting process must not exceed 12 months from the commencement of the drafting process. 62 It is doubtful that the central government can give extensive zoning coaching to 514 regencies and municipalities within such a restrictive time frame.

Besides drafting, enforcement mechanisms also play an essential role in zoning success. There are two types of enforcement mechanisms, namely enforced and voluntary compliance. As provided in Article 62 of Spatial Planning Law, enforced compliance can take the form of notice of removal, license withdrawal, restitution, fines, and demolition. Enforced compliance calls for better-trained personnel and more resources. A specific task force must be assigned to detect zoning violations. The task force can apply current technology such as GIS tools.63 Even if the task force can detect non-compliance, there are still -at least- two concerns regarding enforcing mechanism. First, the 'grandfathering' rules will create complexity because it allows non-compliance with preexisting uses. Tremendous cases of non-compliance must be prosecuted altogether to ensure justice for all. The second concern is the issue of corruption in zoning enforcement. Violators will find a way to avoid sanctions either by correcting the noncompliance or bribing the officers.

Voluntary compliance calls for transparency and simplification of zoning regulation. In order to create compliance, the public must be aware of and understand zoning. Everyone is entitled to access spatial planning regulations, and the government must make the regulations publicly available. 64 Likewise, RDTR must also be publicly available to ensure awareness, compliance, and supervision of RDTR and zoning implementation.65 Besides publishing the law, the government should also raise public awareness regarding spatial planning in creative content on social media, such as infographics. The content must be informative and persuade the public to comply with zoning regulations, offering incentives to those who comply and disincentives for violators. Ignorance of regulations and lack of appreciation of compliance benefits are some reasons for non-compliance. 66 Compliance can only occur when the cost of disobeying the law exceeds the benefits of non-compliance. Landowners find it profitable to ignore restrictive zoning than relocate their business activities to another area. 67 Therefore it is crucial to employ incentives and disincentives to encourage compliance. The procedure and types of incentive and disincentive are regulated under Article 163 to 187 PP 21/2021.

Local authorities must improve staff expertise to detect or correct violations and create conditions under which violations are unlikely to occur. Non-compliance can occur because of ignorance, deliberate violation, or massive non-compliances caused by defects or zoning drafting errors, such as establishing an agriculture zone in Pecatu village that neglects socio-economic factors. Thus, the local authorities must set out the appeal mechanism for errors or defects in zoning regulation. However, the zoning regulation only can be reviewed once every five years unless under exceptional circumstances such as large-scale natural disasters defined by laws, changes to the defined territorial boundaries at the national or provincial level by law, or changes in national strategic policy.68 Under Article 60, everyone has a right to claim compensation for losses caused by zoning. However, the procedure remains unclear. If the claim is brought as a private claim through the civil procedure, the claim should be directed toward the local authority. In Indonesia, there is a mechanism for dispute settlement between individual/legal entities with the government through Administrative Court. However, zoning regulation does not fall into the scope of the administrative court. Under Article 1 (4) Administrative Court Law, the court's competence is limited to a dispute arising from a government decree that is specific, individual, and final. Zoning is a regulation that generally applies to the public; thus, it cannot be tried through administrative court. There are not many alternatives besides illegal means such as bribing or securing interests before zoning is enacted.

Catastrophic impact caused by environmental degradation is happening throughout the world and it requires immediate and real action. Halting deforestation is the cheapest and quickest option to stabilize the climate while shifting to a low-carbon economy. RDTR and zoning regulation can be harnessed as instrument to establish the existing forest as conservation area and allocate additional green area. Despite some constraints in drafting and implementing zoning, nonetheless zoning which integrated to the online licensing system can be effective tool to protect the forest because any business activity within conserved area will be automatically declined. Central government must provide comprehensive manual supplemented with best-practice as example, advise and supervise local authority to ensure favorable investment zoning regulation. On the other hand, RDTR and zoning regulation must accommodate development need and support small-scale business by enabling mix-land use. Furthermore, Local authority must use objective science-based criteria to determine zoning while taking into account socioeconomic condition of local community and enable option for mix-land use. Future research needed to elaborate more concerning technical methods and criteria to establish conservation zone. Zoning and other spatial planning regulations must be simplified and published to raise awareness and compliance as prescribed by Laws and its implementing regulations. In addition, transparency will enable monitoring of regulations drafting and implementation by public. It is very critical to oversee zoning regulation making process all over Indonesia because once enacted, it will be applicable for 20 years under very strict appeal requirements.

References

Badung Regency Regulation Number 7 of 2018 concerning Detailed Spatial Planning and Zoning Regulations of South Kuta Sub-District 2018-2038 (RDTR and Zoning Regulation of South Kuta Sub-District). (2018).

Burruss, Dylan, Luis L Rodriguez, Barbara Drolet, Kerrie Geil, Angela M Pelzel-McCluskey, Lee W Cohnstaedt, Justin D Derner, and Debra P C Peters. “Predicting the Geographic Range of an Invasive Livestock Disease across the Contiguous USA under Current and Future Climate Conditions.” Climate 9, no. 11 (2021): 159.

Choe, Hyeyeong, and James H Thorne. “Integrating Climate Change and Land Use Impacts to Explore Forest Conservation Policy.” Forests 8, no. 9 (2017): 321.

Fischel, William A. “Zoning and Land Use Regulation.” Encyclopedia of Law and Economics 2 (2000): 403–23.

———. “Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (William Fischel),” 2015. Heritage, UNESCO World. Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra. (n.d.).

Korlena, Korlena, Achmad Djunaedi, Leksono Probosubanu, and Nurhasan Ismail. “Zoning Regulation as Land Use Control Instrument: Lesson Learned from United States of America and Singapore.” In Forum Teknik, Vol. 33, 2010.

M, Dixon. Modern Land Law. Routledge., 2021.

Matey, EUNICE. “Exploring the Effects of Zoning Regulation on Land Rights of Use Right Holders in the Context of Customary Land Tenure System in Ashiye, Ghana.” University of Twente, 2016.

Ministry of Environment and Forestry Republic of Indonesia. The State of Indonesia’s Environment 2020 (2021).

Ogunbode, Timothy O, and Janet T Asifat. “Sustainability and Challenges of Climate

Change Mitigation through Urban Reforestation-A Review.” Journal of Forest and Environmental Science 37, no. 1 (2021): 1–13.

Petkova, Elisaveta P, Haruka Morita, and Patrick L Kinney. “Health Impacts of Heat in a Changing Climate: How Can Emerging Science Inform Urban Adaptation Planning?” Current Epidemiology Reports 1, no. 2 (2014): 67–74.

R. Haryanti. “Indonesia Baru Punya 55 RDTR Yang Telah Jadi Perda.” Kompas, 2020. https://properti.kompas.com/read/2020/03/11/100000421/indonesia-baru-punya-55-rdtr-yang-telah-jadi-perda.

Scheffran, J., M. Brzoska, H. G. Brauch, P. M. Link, and J. Schilling. “Climate Change, Human Security and Violent Conflict.” Springer Berlin Heidelberg 8 (2012). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28626-1.

Stolton, Sue, and Nigel Dudley. “Managing Forests for Cleaner Water for Urban Populations.” UNASYLVA-FAO- 229 (2008): 39.

Sultan, Benjamin. “Global Warming Threatens Agricultural Productivity in Africa and South Asia.” Environmental Research Letters 7, no. 4 (2012): 41001.

Udry, Christopher. “Land Tenure.” The Oxford Companion to the Economics of Africa 1 (2011).

United Nations General Assembly. The follow-up to paragraph 143 on human security of the 2005 World Summit Outcome. (2010).

Law and Regulation

Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 5 of 1960 Basic Agrarian Law (Basic Agrarian Law).

Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 11 of 2020 concerning Job Creation (Job Creation Law).

Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 23 of 2014 concerning Regional Government (Local Authority Law).

Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 26 of 2007 concerning Spatial Planning Law.

Municipal Code Enforcement Officers Training and Certification Manual on Zoning and Land Use Regulation.

Ministry of ATRBPN Regulation No. 11 of 2021 concerning Procedures for the Preparation, Review, Revision, and Issuance of Substantial Approval of Spatial Planning Regulations.

Ministry of Environment and Forestry Republic of Indonesia. (2021). The State of Indonesia’s Environment 2020.

29

Discussion and feedback