Forecasting Financial Inclusion and Its Impacts on Poverty and Inequality: A Comparative Study in ASEAN

on

pISSN : 2301 – 8968

JEKT ♦ 17 [1] : 108-125

eISSN : 2303 – 0186

FORECASTING FINANCIAL INCLUSION AND ITS IMPACTS ON POVERTY

AND INEQUALITY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN ASEAN- 5

ABSTRACT

Financial inclusion has played a vital role in eradicating poverty and inequality in some developing countries over the last few decades. In ASEAN, the growth of financial inclusion is so rapid that it reaches every element of society. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine forecasts of financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality in ASEAN. In addition, the study also analyzes the correlation between financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality in ASEAN. The study uses the ARIMA and GMM models for the study period from 2000 to 2022. Projections show that most ASEAN countries have experienced an increase in the long-term financial inclusion index, with Thailand leading the ranking, followed by Malaysia. However, the role of financial inclusion in poverty does not seem to be so significant in the short term, most likely due to the still-difficult access for low-income groups.

Keywords: financial inclusion, poverty, inequality

Klasifikasi JEL: I30, O11, P34

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, financial inclusion has been essential in alleviating poverty and inequality in some emerging nations. The extension of financial services to underserved cultures in several emerging nations serves as evidence of this. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which achieve the goal of "ending poverty," are in line with the growth of financial inclusion since they state that "all men and women, especially the poor and vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, financial services, including microfinance." (United Nations, 2021).

In Southeast Asia, the percentage of the population having access to digital financial services continues to increase. According to the Google-Temasek eConomy Southest Asia Report (2020), the number of digital financial services users in Southeast Asia is estimated to reach 100 million by 2020. In addition, the financial inclusion programs run by governments and financial institutions in Southeast Asia are also growing. For example, the People's Bank of Indonesia (BRI) launched the BRILink program in 2016 to enhance access to financial services in rural areas of Indonesia. As of December 2020, BRILink has opened more than 148,000 financial services across Indonesia. Meanwhile,

several countries in Southeast Asia have introduced laws or policies to promote financial inclusion. For example, in the Philippines, Republic Act No. 11127, or “National Payments Systems Act,” was passed in 2018 to improve the efficiency of payment systems and encourage financial inclusion in the country.

Accelerating access to financial services (financial inclusion), aimed at attracting people who do not have bank accounts into the formal financial system, is now a major concern for policymakers. (Pearce, 2011). There is awareness that a lack of access to finance has a negative impact on economic growth and poverty reduction, as poor people find it difficult to raise savings, build assets to protect themselves from risk, and invest in income-generating projects. Cumming et al. (2014) highlighted the importance of financial access so that people are encouraged to take risks, invest more, and contribute positively to growth.

The important role and positive impact of access to financial services on the socioeconomic conditions of this population are also mentioned in Bangoura et al. (2016) and Miled & Rejeb (2015). A wide range of

financial services can overcome barriers to financial inclusion, with implications for financial intermediation and the socioeconomic, geographical, and cultural characteristics of a population. In this sense, activities in financial intermediary institution, for example, credit, savings, or payment mechanisms, can form financial inclusion for people who previously did not have access to financial services. These people are usually considered to be high-risk, low-payment capacity, unprofitable, and located in very remote areas. In addition, there is also a difference in financial inclusion between private banks and credit financing institutions because of the economic principles of such institutions, making it one of the important facts that banks are capital entities and credit unions for the people (McKillop et al., 2020).

As a result, the study aims to: 1) forecast financial inclusion in ASEAN; 2) examine the relationship between finance, poverty levels, and inequalities in ASEAN countries; and 3) implement relevant policies related to financial inclusion,

poverty levels, and disparity in the South East Asia region.

Financial inclusion can be defined as the expansion of access to and use of financial services for all sectors of society, including people, with the aim of contributing to social and economic development and well-being (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2010; Demirgüç Kunt et al., 2013). Financial inclusion also explains that individuals are given access to an appropriate range of financial services and affordable financial products to meet transaction needs, such as transactions, payments, savings, credit, insurance, and other services. Moreover, financial inclusion also involves access to convenient credit from formal financial institutions, in addition to the use of insurance products that allow the public to alleviate financial risks such as forest fires, earthquakes, floods, and other natural disasters (Demirgüç Kunt et al., 2017; Babajide et al., 2015; Seko, 2019).

According to the World Bank, poverty is a condition in which a group or individual has no choice or opportunity to improve their standard of living and become

independent and better in social life. In 2019, the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) found that the Indonesian people who are among the poor are the population with an income of Rs. 425.250/month. The income means that the figure is a minimum limit that must be met by Indonesians to improve the standard of living in order to be better in terms of food and non-food.

The Central Statistics Agency (BPS) reports that the poverty rate is divided into two parts, the Poverty Depth Index (P1) and the Povety Seriency Index (P2). The Poverty Depth Index (P1) explains the relationship between average expenditures in each community that belongs to the poor category. The total value of P1 represents the cost of poverty alleviation without any transaction costs or inhibitory factors. The lower the P1 value, the greater the potential of the economy to reduce the poverty rate through programs or strategic efforts by the government. Whereas the poverty severity index (P2) explains the distribution of expenditure among the poor.

Atkinson (2015) defines inequality as differences in the distribution of income,

wealth, and opportunity between individuals or groups in a society. Piketty (2014) defines inequity as the increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of a particular group and its increasing distance from the majority of the population. In general, inequality is the difference or inequity in the distribution of resources, opportunities, income, wealth, or quality of life between individuals or groups in a society.

Several studies have shown the positive impact of access to financial services (e.g., credit, savings, and payment methods) on economic development (Beck, 2000; Demirgüç Kunt et al., 2013; Sha’ban et al., 2020). In addition, strong evidence supports the idea that higher financial inclusion reduces poverty and inequality as well as improves the performance of small businesses (Banerjee et al., 2011; Cull et al., 2014; Demirgüç Kunt et al., 2009; Klapper et al., 2016). Other studies show that inclusive financial markets contribute to stimulating economic activity at the local level, improving the socio-economic conditions of the population. (Bae et al.,

2012; Bruhn et al., 2014; Chithra et al., 2013).

The Neaime and Gaysset (2018) research studies how the impact of the MENA banking system can create effective opportunities for financial inclusion and further reduce poverty and income inequality. The study uses the Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) model and the Generalized Least Square (GLS) model with samples from eight MENA countries during the period 2002–2015. The result is that financial inclusion can reduce income inequality. However, financial inclusion has no effect on poverty. Financial integration factors are the cause of financial instability in MENA member states, and financial inclusion contributes positively to financial stability.

Alvarez-Gamboa et al. (2023) studied the relationship between financial inclusion and territorial inequality and compared private banks and alternative financial institutions from social-based economies and solidarity using core component analysis, the financial inclusion index, and non-hierarchical cluster analysis. The results of this study show that there is a

theoretical impairment in access to and use of financial services. It can be concluded that credit unions produce higher rates of financial inclusion in the less fortunate regions of Ecuador, unlike private banks that show high levels of financial inclusiveness in provinces with higher socio-economic status.

Erlando et al. (2020) analyzed empirically the contribution of financial inclusion to economic growth, poverty reduction, and income inequality in East Indonesia. This study uses the Toda-Yamamoto VAR bivariate causality model and the Dynamic Vector Panel Autoregression (P-VAR). The results of the bivariate model show that there is a high degree of correlation between financial inclusion, economic growth, poverty, and income distribution in eastern Indonesia. Socio-economic growth has a positive impact on the level of financial inclusion, but a negative impact on poverty. Meanwhile, financial inclusion has a positive effect on inequalities that result in widespread income inequality in eastern Indonesia.

RESEARCH METHOD

The study uses a quantitative approach as an attempt to establish accurate units in analyzing the relationship between variables. The study period used was 2000–2021. To project financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality in ASEAN, we used the ARIMA model. Meanwhile, to analyze the linkages between financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality in ASEAN, the Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) will be used.

ARIMA is a combination of AR and MA models through differential processes. The time flexibility of a period in an autoregressive process is called the first-order auto-regressive, or abbreviated AR(1). The symbol for indicating the multiplicity of time flexibilities in an autoregressive procedure is p. The time flexibility of one period in a moving average process of the first order is MA(1). A symbol for the multiplication of time flexibility in the moving average is q. The value of p and the value of q can be greater than 1.

The ARIMA model writes for AR(p), MA(q), and the difference as many as d times is ARIMA (p,d,q). For example, in a process where ARIMA uses the

autoregressive of the first order, the moving average of the second order, and is differentiated once to obtain the stationary data, then the writing is ARIMA (1, 1, 1). Gujarati (2003) describes the Box-Jenkins methodology into four steps, including identification, estimation, diagnostic examination, and prediction. For example, we'll make a model to predict the value of Y. The common form of the autoregressive model of order p, or AR(p), is:

Yt = ao + a1Yt-1 + a2Yt-2 + - (1)

+ apYt-p + εt

Information:

Ft : observed variables

a0 : autoregressive constant

a1... ap: parameter Ft-1... Ft-p

The general form of the q-th order moving average model or MA(q) is:

Yt = βo+β1εt-1+β2εt-2 + - (2)

+ βqεt-q

Information:

Yt : observed variables

β0 : autoregressive constant

β1... βq: parameter εt... εt-q

The common form of the ARIMA model

with autoregressive order to p and moving average order to q is:

Yt = ao + aiYt-1 + a2Yt-2 + -+ apYt-p + εt + β1εt + β2εt-1 + - + βqεt-q

(3)

In line with the second objective of this study, namely, to analyze the correlation between financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality, the Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) model will be used.

FIit =Yo+ Y1Fkt-1 + Y2P0vertyit (4)

+ Y3Inequalityit ∑n

Controlit + eit i=1

Further, the model will be estimated using the two-step System-GMM introduced by Blundell and Bond (1998) and Arellano and Bover (1995) to control endogeneity problems in the model.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

ARIMA Estimation Result

The ARIMA model is used to project financial inclusion, poverty rates, and inequalities in ASEAN.

-

a) Best Model Selection

The selection of the best model is based on two criteria: the remainder of the model with the white noise and the smallest AIC value. The first step is to select the model whose remainder has the white noise, and then from the model is seen the least AIC. The model that has been selected can be seen in Table1.

Table 1.

|

Country |

Variable |

Best Model |

Residual autocorrelation function |

AIC |

|

Malaysia |

Inclusion |

ARIMA |

White noise |

85,60 |

|

Index |

(1,1,0) | |||

|

Indonesia |

Inclusion |

ARIMA |

White noise |

86.99 |

|

Index |

(1,1,0) | |||

|

Philippines |

Inclusion |

ARIMA |

White noise |

74,36 |

|

Index |

(1,1,0) | |||

|

Thailand |

Inclusion |

ARIMA |

White noise |

74,61 |

|

Index |

(1,1,1) | |||

|

Vietnam |

Inclusion |

ARIMA |

White noise |

66,32 |

|

Index |

(0,1,3) |

Source: Estimation Data, 2023

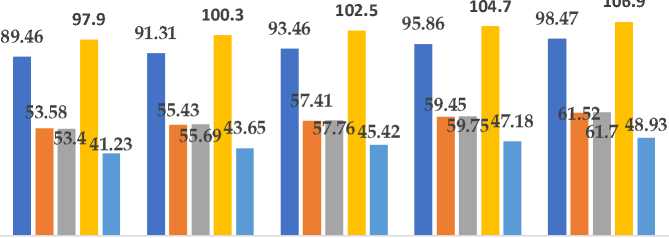

b) Forecasting

Forecasts are made to see the picture for the next five years, that is, from 2022 to 2026. The results can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

|

Country |

Year |

Inclusion Index |

|

Malaysia |

2022 |

89,46 |

|

2023 |

91,31 | |

|

2024 |

93,46 | |

|

2025 |

95,86 | |

|

2026 |

98,47 | |

|

Indonesia |

2022 |

53,58 |

|

2023 |

55,43 | |

|

2024 |

57,41 | |

|

2025 |

59,45 | |

|

2026 |

61,52 | |

|

Phillipines |

2022 |

53,40 |

|

2023 |

55,69 | |

|

2024 |

57,76 | |

|

2025 |

59,75 | |

|

2026 |

61,70 | |

|

Thailand |

2022 |

97,9 |

|

2023 |

100,3 | |

|

2024 |

102,5 | |

|

2025 |

104,7 | |

|

2026 |

106,9 | |

|

Vietnam |

2022 |

41,23 |

|

2023 |

43,65 | |

|

2024 |

45,42 | |

|

2025 |

47,18 | |

|

2026 |

48,93 |

Source : Estimation Data, 2023

GMM Estimation Result

The GMM model is used to identify several variables that influence the financial inclusion index in the ASEAN region.

-

a) Short-term GMM Estimation

Here's the result of a partial parameter significance test. If α is used at 1%, then

Table 4 shows that only last year's Financial Inclusion Index variables and Unemployment Rate have a p-value less than α, so the conclusion is H0 rejected which means both variables have a significant influence on the model.

When α = 10% is used, then the population growth variable has a significant influence on the Financial Inclusion Index.

Table 3. Results of Short-term Estimates of Dynamic Panel Regression Methods

|

Coeff |

Std Error |

Z |

P- Value |

95% Interval |

Conf. | |

|

Inclusion Index_1 |

0,9049 |

0,0277 |

32,68 |

0,000 |

0,8507 |

0,9593 |

|

Poverty |

0,0058 |

0,01387 |

0,42 |

0,675 |

-0,0214 |

0,0330 |

|

Inequality |

0,1537 |

0,1478 |

1,04 |

0,299 |

-0,1361 |

0,4435 |

|

Inflation |

-0,0152 |

0,0098 |

-1,54 |

0,123 |

-0,0344 |

0,0041 |

|

Unemployment |

-0,0802 |

0,0275 |

-2,91 |

0,004 |

-0,1342 |

-0,0263 |

|

Population Growth |

0,0484 |

0,0281 |

1,72 |

0,085 |

-0,0066 |

0,1034 |

|

cons |

-0,9663 |

0,8395 |

-1,15 |

0,250 |

-261,17 |

0.6790 |

Source : Estimation Data, 2023

-

b) Long-term GMM Estimation

Here are the results of partial and longterm parameter significance tests. If the α used is 1%, then Table 5 shows that only the inflation variable has a p-value less than α, so the conclusion is H_0 rejected which means inflation has a significant influence on the model.

When α=5% is used, the Unemployment Rate variable has a significant influence on the Financial Inclusion Index.

In the short or long term, the unemployment rate variable is the only variable that affects the Financial Inclusion Index.

Table 4. Results of Long-term Estimates of Dynamic Panel Regression Methods

|

Coeff |

Std Error |

z |

P- Value |

95% Conf. Interval | ||

|

Inclusion Index_1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Poverty |

0,0613 |

0,111 |

0,55 |

0,580 |

-0,156 |

0,278 |

|

Inequality |

1,617 |

2,636 |

0,61 |

0,539 |

-3,549 |

6,784 |

|

Inflation |

-0,16 |

0,052 |

-3,10 |

0,002 |

-0,261 |

-0,059 |

|

Unemployment |

-0,845 |

0,4023 |

-2,10 |

0,036 |

-1,633 |

-0,056 |

|

Population Growth |

0,51 |

0,52 |

0,98 |

0,327 |

-0,51 |

1,529 |

Source : Estimation Data, 2023

Discussion

Based on the results of the financial inclusion projections using the ARIMA model, it shows that a total of five (five) countries in ASEAN will have experienced an increase in the financial inclusive index by 2026. In this projection, Thailand leads the inclusion index, with an estimate of the index reaching 106.9 in 2026. This is supported by the Bui & Luong study (2023), in which the Thai government has contributed to further developing financial inclusion, especially for the population over the age of 60. Besides, the need for financial inclusion among older segments of the population is sometimes neglected

or diminished. Parents may be very vulnerable to economic fluctuations like recessions, and they may be less profitable because of a poor understanding of the financial impact on their well-being of social welfare institutions. (Fenge, 2012).

In a few previous periods, Thailand also had a reputation for managing financial inclusion. This is proved by being ranked fifth in the top quarter in financial inclusion among countries in the Asia Pacific, along with developed countries such as South Korea and Singapore, and by being considered the benchmark of territorial borders (Loukoianova et al.,

-

2018). The full forecasting data for below.

financial inclusion is presented in Figure 1

Figure 1. Forecasting of the Financial Inclusion Index in ASEAN

■ Malaysia ■ Indonesia ■ Filipina ■ Thailand ■ Vietnam

2022 2023 2024 2025 2026

Source: Estimation Data, 2023

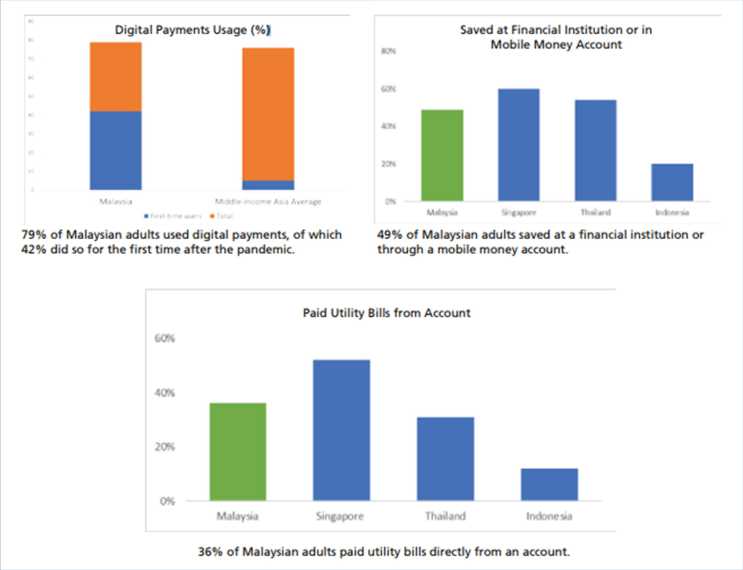

Meanwhile, Malaysia ranks second in the ASEAN financial inclusion projections. The 2021–2022 Financial Capability and Inclusion Demand Side Survey (FCI Survey 2021–2022) estimates that 74% of Malaysians use digital financial services (DFS). In addition, the World Bank’s Global FINDEX Report (2021) revealed

that 79% of Malaysian adults used digital payments, of which 42% did it for the first time during the pandemic. In turn, receiving digital payments has catalyzed the use of other financial services, including savings and loans. This is the development of Digital Financial Services (DFS) in Malaysia.

Figure 2. Development of Digital Financial Services (DFS) in Malaysia

Source : Sumber: World Bank’s Global FINDEX Report (2021)

Indonesia ranks fourth in financial inclusion predictions, competing thinly with the Philippines. In the Philippines, raising financial literacy remains a challenge. The World Bank (2015) concluded that the Philippines, at the national level, lacked knowledge of basic financial concepts. The results of BSP's subsequent survey were the same. (BSP, 2019; BSP, 2022). Meanwhile, Indonesia has established a comprehensive approach in the National Strategy for Financial Inclusion to address this. It aims

to improve financial education in the country, deal with public property rights, and improve channels of intermediation and distribution, government financial services, and consumer protection.

The program also supports the launch of the world's first self-financial inclusion strategy for women to address gender disparities in financial inclusion. The strategy sets national targets for women's financial inclusion, introduces the first national definition of being owned or run by women, and establishes a national

network of women's financial inclusion. The program also focuses on youth, the demographic key to financial inclusion. About 26% of the country's population are millennials. To reach this sector, OJK, with the support of the program and in collaboration with ADB Youth for Asia, launched the world's first youth financial inclusion strategy. To support this strategy, the Youth Finsights Survey was conducted to better understand the status, behavior, and objectives of Indonesian youth financial inclusion and to enable them to contribute to the financial inclusive initiatives. A program for young national ambassadors who will act as influencers at universities and on social media is also being launched to raise financial awareness among young people.

The program helped OJK develop and adopt a Roadmap Team for Acceleration of Regional Financial Access (TPAKD) to address regional differences in financial inclusion. It describes policies and regulations at the subnational level over the next five years, with programs like digital finance, sharia finance, non-bank financial services, and capital markets. He

also supported OJK in launching the Eastern Indonesia Financial Innovation Lab (EIFIL) to enable regional development banks (BPD) to collaborate with the fintech sector to become champions of financial inclusion. EIFIL collaborators map customer needs, design and develop new financial products, and digitize operations while building staff competence. It helps BPD accelerate digital transformation and credit expansion.

Financial inclusion has no effect on poverty. This may be because low-income communities still have difficulties accessing financial services. In this case, financial inclusion may not reduce poverty. In contrast, people who already have higher income rates or larger assets are finding it easier to access better financial services. Moreover, inclusive inclusion has no effect on poverty because the cost and high interest rates on loans or other financial products can make it difficult to access financial services, which can keep people in poverty.

Financial inclusion has no effect on poverty because access to bank accounts

or financial products does not guarantee that a person has sufficient knowledge or skills to manage finances well. The inability to manage money wisely can still lead to financial difficulties. Finally, poverty is often linked to deeper structural problems in a society, such as corruption, a lack of employment opportunities, income inequality, and a lack of access to basic resources. Financial inclusion may not be able to address these problems directly. These statements are supported by the fact that financial inclusion has no impact on poverty (Neaime & Gaysset, 2018). The findings of this study are also supported by Ouechtati (2020), who found that financial inclusion has a negative but insignificant impact on poverty.

The results of the study indicate that inequalities have no influence on financial inclusion or inequality. For example, Wong's research, the DKK (2023) found that financial inclusion accompanied by financial innovation can increase income inequality. This is due to the inequality in the benefits of digital financial innovation, which tends to be more profitable for

high-income segments. Meanwhile, low-income segments tend to have difficulty accessing the necessary smart devices and internet services and have a lower level of financial literacy, so they do not get the same benefits as the high-income segments. These findings suggest that future financial innovation must focus on sustainability and continue to enhance financial inclusion, focusing on the needs of low-income communities.

In contrast, Verma, dkk (2022), in his research, revealed that financial inclusion has a significant impact on reducing income inequalities in Asia. In the long term, income disparities are heavily influenced by indicators of financing inclusion, such as the number of branches of banks, deposit accounts, outstanding loans, and domestic loans to the private sector. This research has made important contributions by filling gaps in the literature on the role of financial inclusion in addressing income inequalities in Asian countries that have experienced impressive growth in financial inclusion initiatives in the last decade but are still facing widening income disparities.

Finally, on the results of research that suggests the relationship between financial inclusion and inequality in Indonesia conducted by Erlando, dkk (2020), In his research, he explained that financial inclusion has a positive and significant impact on inequality. While having a positive effect on economic growth and reducing poverty levels, financial inclusion also contributes to wider income inequality in Eastern Indonesia. In other words, while it can improve overall economic well-being, financial inclusiveness also potentially increases income disparities among communities.

Poverty remains a problem in several countries, including Indonesia. According to the World Bank (2023), more than a third of Indonesians are still economically unsafe. They can be pushed into poverty after shocks like COVID-19 or natural disasters, whose frequency and severity are increasing due to climate change. On the road to high income, poverty reduction policies in Indonesia need to be expanded through a diverse approach: creating better opportunities, protecting

households from poverty, and focusing fiscal resources on pro-poor investment while promoting better information and evidence for decision-making.

Policies can support the private sector to create better and more productive jobs in the context of climate change, the ongoing redesign of the global value chain (GVC), and digitization. A combination of social assistance, social security, financial inclusion, and sustainable infrastructure investment can help keep households out of poverty. Increased tax revenues and the elimination of inefficient subsidies could create fiscal space for pro-poor investment, while increased capacity in sub-national administrations could improve public services.

In developing a master plan, it is important to understand the changing scenarios that shape rural development in the ASEAN region. Similarly, the links between rural development, agricultural development, and food security need to be uncovered in order to better understand, plan, and address the challenges that will be faced. In the same way, reviewing agroecological concepts

can help, as this is an approach that simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles and can be a critical response to the number of instabilities currently felt in agriculture and food systems. (AFS).

CONCLUSION

This study's forecasts provide significant insights for more effective policy planning. According to projections, most ASEAN countries have seen an increase in the long-term financial inclusion index, with Thailand leading the way, followed by Malaysia. However, the role of financial inclusion in poverty does not appear to be as substantial in the short term, most likely due to low-income people' continued lack of access.

These findings have policy implications, including the necessity for a multifaceted strategy to reducing poverty through the creation of opportunity, social security, and pro-poor investment. Furthermore, the private sector can help to create better and more productive jobs. Tax increases and the elimination of wasteful subsidies can create fiscal space for pro-poor initiatives. Then, for improved policy

planning, a good grasp of the shifting scenarios in rural development and the interaction between rural development, agriculture, and food security is required.

The main conclusion to be drawn from this study is that financial inclusion does not necessarily have a favorable influence on poverty. In efforts to minimize inequities, some underlying structural causes must also be addressed. This inference emphasizes the complexities of the ASEAN context's interaction between financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality.

REFERENSI

Alliance for Financial Inclusion. (2010). Financial inclusion measurement for regulators: survey design and implementation.

Alvarez-Gamboa, J., Cabrera-Barona, P., & Jacome-Estrella, H. (2020). Territorial inequalities in financial inclusion: A comparative study between private banks and credit unions.

Arun, T., Kamath, R., 2015. Financial inclusion: policies and practices. IIMB Manag. Rev. 27 (4), 267–287

Babajide, A.A., Adegboye, F.B., Omankhanlen, A.E., 2015.

Financial inclusion and economic growth in Nigeria. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 5 (3), 629–637.

Bae K, Han D, Sohn H. (2012). Importance of access to finance in reducing income inequality and poverty level. Int. Rev. Public Adm. (17), pp. 55–77.

Banerjee AV, Duflo E. (2011). Poor economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. Hachette UK.

Bangoura L, Mbow MK, Lessoua A, Diaw D. (2016). Impact of microfinance on poverty and inequality: a heterogeneous panel causality analysis. Rev. D´ economie Polit., pp. 126:789–818.

Beck T, Levine R, Loayza N. (2000). Finance and the sources of growth. J Financ Econ. (58), pp. 261–300.

Boukhatem, J., (2016). Assessing the direct effect of financial development on poverty reduction in a panel of low-and middle-income

countries. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 37, 214–230.

Bruhn M, Love I. (2014). The real impact of improved access to finance: evidence from Mexico. J Finance, (69), 1347–76.

Bui, M.T., & Luong, T.N.O. (2023). Financial inclusion for the elderly in Thailand and the role of information communication technology. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23-4, 818-833.

Chithra N, Selvam M. (2013). Determinants of financial inclusion: an empirical study on the inter-state variations in India. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

Cull R, Ehrbeck T, Holle N. (2014). Financial inclusion and

development: recent impact evidence. Washington, D.C: CGAP.

Cumming, D., Johan, S., Zhang, M., 2014. The economic impact of entrepreneurship: comparing

international datasets. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 22 (2), 162–178.

Demirgüç Kunt A, Klapper L. (2013). Measuring financial inclusion: explaining variation in use of financial services across and within countries. Brookings Pap Econ Activ, pp. 279–340.

Demirguc-Kunt A, Klapper L, Singer D.

(2017). Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: a review of recent empirical evidence. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Erlando, A., Riyanto, F.D., & Masakazu, S.

(2020). Financial Inclusion, Economics Growth, and Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from

Eastern Indonesia.

Fenge, L.-A. (2012). Economic well-being and ageing: The need for financial education for social workers. Social Work Education, 31(4), 498–511.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0261547 9.2011.579095

Klapper L, El-Zoghbi M, Hess J. (2016). Achieving the sustainable development goals: the role of financial inclusion. Washington, DC: CGAP.

Loukoianova, M. E., Yang, Y., Guo, M. S., Hunter, M. L., Jahan, M. S., Jamaludin, M. F., Rawat, U., Schauer, J., Sodsriwiboon, P., & Wu, M. Y. (2018). Financial inclusion in asia-pacific. International Monetary Fund.

McKillop D, French D, Quinn B, Sobiech AL, Wilson JOS. (2020). Cooperative financial institutions: a review of the literature. Int Rev Financ Anal. (71):101520.

Miled KBH, Rejeb J-EB. (2015). Microfinance and poverty reduction: a review and synthesis of empirical evidence. Procedia -Soc. Behav. Sci., pp. 195:705–12.

Neaime, S., Gaysset, I. (2018). Financial Inclusion and Stability in MENA: Evidence from Poverty and Inequality. Finance Research Letters.

Ouechtati (2020). The Contribution Of Financial Inclusion In Reducing Poverty And Income Inequality In Developing Countries. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 10(9), 1051-1061.

Pearce D. (2011). Financial Inclusion in the Middle East and North Africa, The World Bank Middle East and North Africa Region, Financial and Private Sector Development Unit.

United Nations. (2021). Sustainable development goals. Goal 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Erlando, A., Riyanto, F. D., & Masakazu, S. (2020). Financial inclusion, economic growth, and poverty alleviation: evidence from eastern Indonesia. Heliyon, 6(10), e05235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05235

Verma, A., & Giri, A. K. (2022). Does financial inclusion reduce income inequality? Empirical evidence from Asian economies. International Journal of Emerging

Markets, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print).

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-02-2022-0271

Wong, Z. Z. A., Badeeb, R. A., & Philip, A. P. (2023). Financial Inclusion, Poverty, and Income Inequality in ASEAN Countries: Does Financial Innovation Matter? Social Indicators Research, 169(1), 471– 503.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03169-8

125

Discussion and feedback