CARBON STOCK DUE TO THE INTENSITY OF THE USE OF FOREST AREAS IN FOREST MANAGEMENT UNIT OF WEST BALI

on

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

CARBON STOCK DUE TO THE INTENSITY OF THE USE OF FOREST AREAS

IN FOREST MANAGEMENT UNIT OF WEST BALI

Wiyanti 1*, Indayati Lanya 1, I Nyoman Merit1, I Made Antara2

-

1Department of Agroecotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Udayana University, Bali

2

-

2 Department of Agribusiness, Faculty of Agriculture, Udayana University, Bali

* Corresponding author : wiyanti1259@gmail.com

Received : 21st May 2016 | Accepted : 25th August 2016

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to determine the magnitude of the changes in carbon stocks due to changes in forest utilisation. Location of the study include planted forests, coffee plantations, mix garden, and cajuput region. The method used in this study was to estimate carbon stock based on the weight of biomass both above the surface and underground. Measurements were made on the biomass of trees and undergrowth, necromass (dead plant parts), both woody and non-woody (litter), and reserve C in the soil. The results showed that there were considerable differences of carbon stock in each area utilisation. The highest carbon stock found in the mix garden (275.62 tonnes/ha), then decrease at mahogany forest (269.63 tonnes/ha), planted forests (231.45 tonnes/ha), old cajuput (Melaleuca cajuput) (118.53 tonnes/ha), trimmed cajuput (86.57 tonnes/ha), coffee plantations (74.37 tonnes/ha), and un-trimmed cajuput (56.78 tonnes/ha). The recommendation can draw out in this research are: ( 1 ) In the area of coffee planting, horticultural forestry can be developed in the form of rows of plants among the coffee plants and ( 2 ) cajuput planting can be done with the system surjan and each row of cajuput consists of 2 rows with a distance planting more tightly.

Keywords : carbon stock, forest area, biomass

INTRODUCTION

Forests are the natural resources that are critical in supporting the process of life. Forests as a regulator of the water system, micro-climate regulation, aesthetic function, as a provider of oxygen and carbon sinks. According to Zain (1996) the existence of forests as a sub-global ecosystem occupies an important composition as lungs world. Sumarwoto (2001) explain that forests includes hydro-orologis functions,

storage of genetic resources, forest soil fertility control, and climate as well as carbon storage and biodiversity storage. Forests are very important in tackling climate change and the amount of pollution contained in the scheme of Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), which was later expanded to REDD + (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, conservation efforts, nutrient

ISSN ONLINE: 9 772303 337 008

management sustainable and enhancement of carbon stocks) (Butar-Butar, 2011). According Trexler and Hogen (1994), Brown et al. (1996) and Watson et al. (2000), the forest ecosystem plays a very important in climate change because it can be as sources and sinks of carbon dioxide (CO2) and are able to regulate the assimilation of CO2 through photosynthesis and storing the carbon in the biomass and soil.

Carbon stocks stored in the biomass form, thus decreasing the level of forest density, the carbon stocks also declined. Transitional land use or forest land use change lead to the increase of carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere and increased mineralisation of soil organic matter during land clearance and reduced vegetation as the carbon source. Decreased function of forests as carbon stocks can increase the effect of greenhouse gases that can cause a rise in temperature at the earth's surface.

Natural forests are the highest storing carbon (C) when compared with the system of agricultural land use due to high tree diversity (Hairiah and Rahayu, 2007). Further, the natural forest with a diversity of plants that has

a long-life and litter, the highest become carbon reserves, when compared with the forests that have been converted for agriculture or plantations. A system of land use which consists of tree species that have a high wood density value, the biomass will be higher when compared to the land that has species with low wood density value (Rahayu et al, 2007). According to Ullah and Al-Amin (2012), found that 38% of carbon stocks in trees, 3% in the bushes and 59% in soil and litter fall.

Forest area in the province of Bali is 130,766.06 ha or 22.42% of the land area. These areas do not meet minimum standards, namely 30%. According to the Bali Provincial Forestry Office (2005) of the total of land area, 66,763.41 ha (51.06%) were in the Forest Management Unit of West Bali. Forests dominates the region of West Bali is in the form of protected forest area of 59,223.71 hectares (88.71%), the rest is a production forest area covering an area of 7,539.70 ha (11.29%).

Based on field observations and data from the Bali Provincial Forestry Office (2005), that the condition of forests in the Forest Management Unit

of West Bali was damaged, resulting in less function optimally. The forest damage due to natural conditions less-favored areas in terms of both climate and soil physical conditions that cause impaired plant growth. It is also caused by the tapping of staple crops and illegal logging. Cropping system between forest trees with agricultural crops and forest plantations by the local community is also a cause of forest destruction is quite prominent. Encroachment occurs in almost all slaughterhouses (Resort Forest Management), as happens in slaughterhouses Pulukan which encroached by planting tree crops, such as bananas and chocolate and the most severe in the RPH Antosari.

The pressure on the forest, especially in the area of West Bali caused by forest destruction is increased, resulting in a decrease in the amount of biomass that is a source of carbon stocks. According to Page (2007) that the release of carbon into the atmosphere as a result of forest conversion amounted to about 250 mg/ha which occurs during the logging and burning, while the re-absorption of carbon into biomass wood is relatively slow, only about 4.5 to 5 mg/ha/year.

Based on these descriptions, the authors conducted a study that aimed to determine what extent a decrease in carbon stocks in forests of West Bali due to changes in forest use. Measured the amount of carbon stored in the body of plant life (biomass) in the landscaped can describe the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is absorbed by plants (Hairiah and Rahayu, 2007).

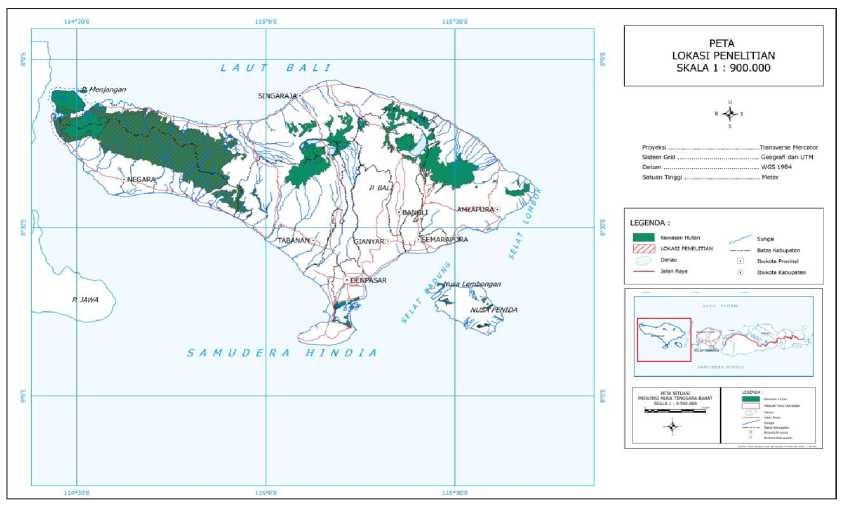

Research sites

The study was conducted in the area of Forest Management Unit (FMU) of West Bali (Figure 1.). The selection of the location is based on the level of forest destruction. Based on field observations established that the research conducted in the area Sumberklampok and Badingkayu. The study was conducted for 8 months starting from exploratory of locations to writing the report.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

The materials used in this study were chemicals for analysis of soil organic C-form: K2Cr2O7, concentrated H2SO4, H3PO4 concentrated, DPA (diphenylamine) and FeSO4 0.1 N for titration. The tools used in this study include raffia rope, tape measure, wood rectangular plots, books for notes, markers, plastic bags, and oven.

ISSN ONLINE: 9 772303 337 008

Figure 1. The Location of the Research

The methods used in this research ware the method of sampling without harvesting (non-destructive sampling) and harvesting (destructive sampling). The non-destructive sampling method for measuring biomass harvesting live trees, dead trees and dead wood and the destructive sampling method for measuring biomass harvesting undergrowth and litter (Hairiah and Rahayu, 2007). Calculation of carbon stocks in plants was done by estimation using the formula: Levels of C = dry weight biomass or necromass (tonnes/ha) x 0.46% (Hairiah, et al., 2011). Biomass consists of the biomass of trees and undergrowth, necromass (dead plant parts), both woody and non-woody (litter), and reserve C in the

soil. Calculation of tree biomass above ground done using allometric equations. The equation used is presented in Table 1.

Measurement of biomass was done by several stages, namely: (1) creating permanent plots (transects measurement), (2) measuring the volume and biomass of trees, and (3) measuring the biomass of undergrowth. The size plots of varying depending on the density and plant diameter (Hairiah et al., 2011), namely:

-

1) Plot size of 40 m x 5 m for natural forests, shrubs, and agroforestry with high-density level. Trees were measured with a diameter of

5 cm - 30 cm (tree circumference 15-95 cm)

-

2) Plot size of 100m x 20m, if in the plot there are trees with a

diameter> 30 cm (95 cm

circumference of the tree).

-

3) Rectangular plots with a size of 50 cm x 50 cm of wood to limit the collection of undergrowth biomass. The weight of undergrowth biomass was calculated by weighing.

Necromass divided into two groups, namely woody necromass and non-woody necromass. Necromass of woody plant is dead trees that are still standing or fallen, the stubble of plants, branches and twigs intact with a

diameter ≥ 5 cm and a length ≥ 0.5 m. Necromass of non-woody is in the form of leaf litter that is still intact (coarse litter), and other organic materials that are already partially decomposed size> 2 mm (fine litter).

Necromass divided into two groups, namely woody necromass and non-woody necromass. Necromass of woody plant is dead trees that are still standing or fallen, the stubble of plants, branches and twigs intact with a diameter ≥ 5 cm and a length ≥ 0.5 m. Necromass of non-woody is in the form of leaf litter that is still intact (coarse litter), and other organic materials that are already partially decomposed size> 2 mm (fine litter).

Table 1. Equation Allometric used to Carbon Stock Estimation of Forest Area in West Bali Forest Management Unit.

|

Equation |

Specification |

|

(AGB)est = ᴫ* exp (-0.667 + 1.784 ln (D) + 0.207 |

Dry Climate |

|

(ln(D))2 - 0.0281(ln(D))3) |

(Sumberklampok village) |

|

(AGB) ᴫ est = exp (-1.499 + 2,148ln (D) +0.207 (ln |

Humid (Badingkayu |

|

(D)) 2-0.0281 (ln (D)) 3) |

village) |

|

(AGB) est = 0,281D2,06 |

For trimmed Coffee |

|

AGB) est = 0,1208D1,98 |

For cocoa |

|

(AGB) est = 0,0,030D2,13 |

For banana plants |

(AGB) est = upper ground tree biomass (kgs / tree), D = the diameter of trunk at breast height (cm), ᴫ = density of plants (g / cm3). Source: Chave et al., 2005

ISSN ONLINE: 9 772303 337 008

Woody necromass measurement was done by measuring the diameter or length or girth and height of all trees either fallen or still standing. For plants that are still standing in diameter measured at 1.3 m above ground level, while for fallen trees, branches, twigs and stumps performed on both ends. Necromass measurement of non-woody litter consists of coarse and fine. Biomass sampling was done in the same way of lower plant biomass sampling.

a. Measurement of carbon reserves in the soil

Soil sampling for soil carbon measurements carried out to a depth of 30 cm and the depth was divided into three, namely: 0-10 cm, 10-20 cm and 20-30 cm. The method used for the measurement of soil carbon (C-organic) was a method of Walky & Black (Soil Conservation Service, 1972).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

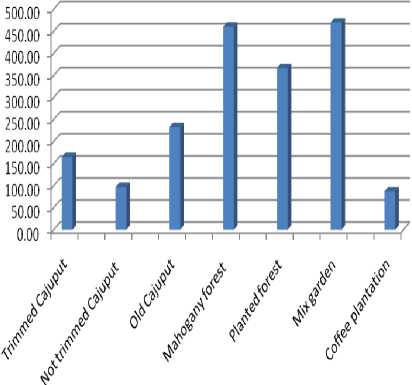

Based on the results, change in carbon stocks due to changes in the utilisation of forest areas. The complete results of estimation of carbon stocks in various forest utilisation in FMU of West Bali are presented in Figure 2.

Tonnes/ha

Figure 2. Estimated Total Carbon Stock in Different Utilization of Forest Area in Forest Management Unit of West Bali

Based on the image it can be seen that the largest carbon stocks contained in the area use as a mixed plantation of 275.62 tonnes/ha, followed mahogany forests of 269.63 tonnes/ha, planted forests amounted to 231.45 tonnes/ha, the old cajuput at 118 , 53 tonnes/ha, trimmed cajuput by 86.57 tonnes/ha, coffee plantation amounted to 74.37 tonnes/ha and the lowest was in not trimmed cajuput by 56.78 tonnes/ha. The high carbon stocks due to the mixed garden conditions in this region comprise a mixture of different types of plants with high enough density and with an average diameter that is greater than others. According to Hairiah and Rahayu (2007), the long-lived plants or

trees that grow in the forest or in the mixed garden (agroforestry) the landfill or storage C (C = C sink) much larger than annual crops. Nurmasripatin, et al. (2010) stated that a number of carbon stocks is determined by the ability of the forest area in building stands tall and large diameter and is also influenced by the type of crops grown, the planting site conditions and silvicultural techniques or intensity of maintenance.

In the region of cajuput intercropped with annual crops, carbon stocks, in general, was relatively low compared to the others because the cropping system that is applied using a fairly wide spacing (3 m x 4 m), so the number of plants per unit area is relatively small. This was done in order to get a wider field of fitness to perform system intercropped with annual crops. The highest carbon stocks was found in old cajuput. These plants have lived over 20 years (planted during the 1980s), the diameter of the tree was already big, and this caused higher carbon stocks than other plants of cajuput that are still young. Young plants are aged about 8 years (planted around the year

2007), so it is still relatively small diametre which causes potentially less biomass. Reduced the potential of biomass will directly impact the ability of plants to store carbon. It may be due to forest fires, timber extraction, land uses for agriculture and other activities carried out in forest areas. Forest changed its function into farmland or plantations or grazing land will lead to deterioration of the carbon stocks stored (Bakri, 2009). Furthermore Murdiyanto, et al. (2004) said that the illegal logging activity will cause a decrease in carbon stocks on the surface (above-ground carbon stocks) and will further affect the shrinkage of carbon stocks below the surface (below-ground carbon stocks).

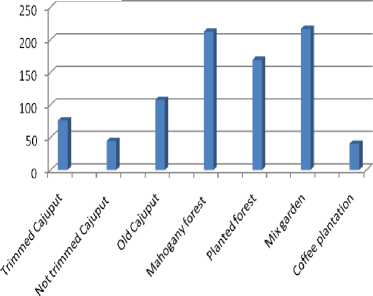

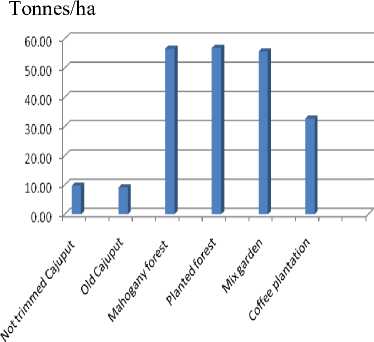

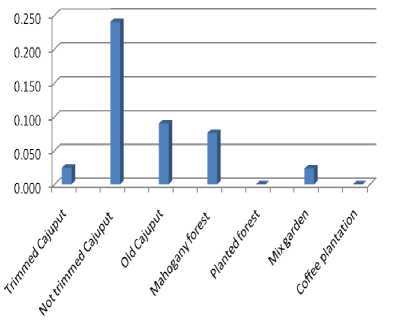

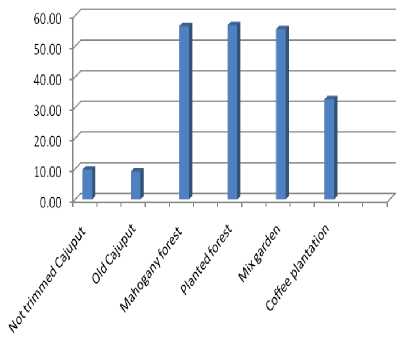

Total carbon stocks components was composed of tree biomass (canopy and roots) as shown in Figure 3, woody necromass (Figure 4), not woody necromass (litter) (Figure 5), and soil carbon stock (Figure 6). In addition, there are plant components at undergrowth but only in not trimmed Cajuput at 1.02 tonnes/ha and forest plantations amounted to 9.09 tonnes/ha.

Tonnes/ha

Figure 3. The Tree Biomass (Canopy and Root ) on the Different Utilization of Forest Area in Forest Management Unit of West Bali

ISSN ONLINE: 9 772303 337 008

Figure 6. Total Reserves Soil Carbon in Various Utilization of Forest Area in Forest Management Unit of West Bali

Tonnes/ha

Figure 4. The Woody Necromass on a Variety Utilization of Forest Area in

Forest Management Unit of Bali Barat

Tonnes/ha

Figure 5. Not Woody Necromass ( litter ) at Various Utilization of Forest Area in Forest Management Unit of West Bali

The constituent components of forest carbon stocks in the FMU of West Bali can be explained that the greatest contribution to the total carbon stocks is tree biomass (plant canopy and root). It means that the diameter of the tree will determine how much carbon stocks in a cropping system. According to Rahayu, et al. (2007) that the presence of trees with diameter > 30 cm in a land use systems that provide a significant contribution to total carbon stocks.

The highest tree biomass was found in mixed garden cropping systems of 216.19 tonnes/ha, then decrease, respectively in mahogany amounted to 211.85 tonnes/ha of plantation forest of 168.64tonnes/ha, the old cajuput of 107.19 tonnes/ha, trimmed cajuput by 75.85 tonnes/ha,

not trimmed cajuput by 44.48 tonnes/ha, and the smallest found in coffee plantations of 40.18 tonnes/ha. The woody necromass found in nontrimmed cajuput by 0.24 tonnes/ha, followed by a long Cajuput (0.09 tonnes/ha), mahogany (0.076 tonnes/ha), and the smallest in trimmed cajuput and mixed farms (0,024 tonnes/ha). The content of litter, mostly in the garden mix (8.35 tonnes/ha), then decreased successively, namely: Cajuput long (4.79 tonnes/ha), cajuput not trimmed (4.3 tonnes/ha), forest plantations (3.835 tonnes/ha), Cajuput crop (3.48 tonnes/ha), coffee plantation (3.26 tonnes/ha), and the smallest one is in mahogany plants (2.56 tonnes/ha). The content of carbon in the soil also varies and the amount in mahogany forests, plantations forest and mix gardens almost the same, which amounted to 56.56 tonnes/ha, 56.87 tonnes/ha, and 56.58 tonnes/ha, while the coffee plant for 32.69 tonnes/ha, and in cajuput area also has almost the same carbon content (cajuput non-trimmed 9.75 tonnes/ha, trimmed cajuput 9.11 tonnes/ha, and old Cajuput by 9.10 tonnes/ha).

ACKNOWLEGMENT

The authors acknowledge the financial support received from The Higher Education Directorate General of The Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia with doctoral grant contract : No.

100/UN14.2/PNL.01.03.00/2015.

REFERENCES

Bakri. 2009. Analisis Vegetasi Dan Pendugaan Cadangan Karbon Tersimpan Pada Pohon Di Hutan Taman Wisata Alam Taman Eden Desa Sionggang Utara Kecamatan Lumban Julu Kabupaten Toba Samosir. Thesis. Sekolah Pasca Sarjana Universitas Sumatra Utara. Medan.

Brown, S., Sathaye, J., Cannel, M. dan Kauppi, P. 1996. Management of Forest for Mitigation of Green House Gass Emission. In Watson, R.T. et al. (Eds). Climate change 1995 : Impacts, Adaptations, and

Mitigation of Climate Change : Scientific-Technical Analysis.

Butar-Butar, T. 2012. Agroforestri untuk Adaptasi dan Mitigasi Perubahan Iklim (Agroforestry Mitigating and Adapting Climate Change). Jurnal Analisis Kebijakan Kehutanan. Vol 9 (1) : 1-12.

Chave, J., C. Andalo, S. Brown, M. A. Cairns, J. Q. Chambers, D. Eamus, H. Fo¨lster, F. Fromard N. Higuchi, T. Kira, J.-P. Lescure, B. W.

Nelson H. Ogawa, H. Puig, B.

Riera, T. Yamakura. 2005. Tree allometry and improved estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Ecosystem Ecology 145: 87–99 DOI 10.1007/s 00442-005-0100-x

ISSN ONLINE: 9 772303 337 008

Dinas Kehutanan Provinsi Bali. 2005. Rencana Unit Pengelolaan

Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan Produksi (KPHP) Provinsi Bali. Denpasar.

Hairiah, K. dan Rahayu, S. 2007. Pengukuran Karbon Tersimpan di Berbagai Macam Penggunaan Lahan. Bogor : World Agroforestry Centre.

Hairiah, K., Andree Ekadinata, Rika Ratna Sari, dan Subekti Rahayu. 2011. Petunjuk Praktis Pengukuran Cadangan Karbon : dari Tingkat Lahan ke Bentang Lahan. Edisi ke 2. Bogor, World Agroforestry Centre, ICRAF SEA Regional Office, University of Brawijaya (UB), Malang, Indonesia xx p.

Noordwijk, M.V., F. Agus, D. Suprayogo, K. Hairiah, G. Pasya, B. Verbist dan Farida. 2004. Peranan Agroforestri dalam Mempertahankan Fungsi Hhidrologi DAS. Dampak

Hidrologis Hutan, Agroforestry dan Pertanian Lahan Kering sebagai Dasar Pemberian Imbalan Kepada Penghasil Jasa Lingkungan di Indonesia. Prosiding Lokakarya di Padang/Singkarak Sumatera Barat, Indonesia, 25-28 Pebruari 2004.

Nur Masripatin, Kirsfianti Ginoga, Gustan Pari, Wayan Susi Dharmawan, Chairil Anwar Siregar, Ari Wibowo, Dyah Puspasari, Arief Setiyo Utomo, Niken Sakuntaladewi, Mega Lugina, Indartik, Wening

Wulandari, Saptadi Darmawan, Ika Heryansah, N.M. Heriyanto, H. Haris Siringoringo, Ratih

Damayanti, Dian Anggraeni, Haruni Krisnawati, Retno Maryani, Dana Apriyanto, Bayu Subekti. 2010. Cadangan Karbon pada berbagai Tipe Hutan dan Jenis Tanaman di Indonesia. Penerbit: Pusat

Penelitian dan Pengembangan Perubahan Iklim dan Kebijakan. Kampus Balitbang Kehutanan Jl. Gunung Batu No. 5 Bogor.

Page, A. C. 2007. Summary of Carbon Uptake and Storage Potensial of Manage Forest in New England. CO2 Recovery in Managed Forest Option for Next Century.

Rahayu, S, B. Lusiana, dan M. van Noordwijk. 2007. Pendugaan Cadangan Karbon di Atas

Permukaan Tanah Pada Berbagai Sistem Penggunaan Lahan di Kabupaten Nunukan, Kalimantan Timur. Bogor: World Agroforestry Centre.

Soil Conservation Survice. 1972. Soil Survey Laboratory Methods and Procedures for Collecting Soil Samples USDA, USA Govt Printy Office. Washington. USA.

Sumarwoto, O. 2001. Atur Diri Sendiri Paradigma Baru Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup.

Trexler, M. C. dan Haugen, C. 1994. Keeping in Green : Tropical Forestry Opportunities for

Mitigating Climate Change. World Resources Institute, Washington's, D. C.

Ullah, M.R. and M. Al-Amin. 2012. Above-and Below-ground Carbon Stock Estimation in a Natural Forest of Bangladesh. Journal of Forest Science, 58, 2012 (8) : 372 – 379.

Watson, R.T., Noble, I. P. Bolin, B., Ravindranath, N. H., Verado, D. J., dan Dokken, D. J. (Eds). 2000. Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Zain, AS. 1996. Hukum lingkungan

Konservasi Hutan. Penerbit Rineka Cipta. Jakarta.

58 • ASIA OCEANIA BIOSCIENCES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY CONSORTIUM

Discussion and feedback