Digital Surveillance of Health and Safety Hazards at Tourist Attractions in Bali: First Preliminary Evidence

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.7. No.1. (2020): 168-176

Digital Surveillance of Health and Safety Hazards

at Tourist Attractions in Bali:

First Preliminary Evidence

I Md Ady Wirawan1,2, Wayan Citra Wulan Sucipta Putri1, Ngurah Agus Sanjaya ER3, Made Agus Hendrayana2, Ni Made Dian Kurniasari1, Ketut Hari Mulyawan1

1Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University 2Travel Medicine Research Group, Health Research Centre, LPPM, Udayana University 3Department of Informatics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Udayana University

Corresponding Author: ady.wirawan@unud.ac.id

ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT

|

Received 01 March 2020 Accepted 20 March 2020 Available online 31 March 2020 |

This study examined the feasibility of conducting digital surveillance of health and safety hazards through a system that can be accessed by travelers using their mobile phones. A progressive mobile website and a mobile application were developed employing a research database which consists of hazards, risks and health facilities that have been geo-tagged and mapped based on their respective geographical positions in 197 tourist attractions in Bali. The system was launched in 80 strategic tourist attractions in Bali at the end of August 2019. Trends in some specific diseases, hazards, and risks were observed monthly using a keyword analysis. Serial data for the first four months were analyzed and presented descriptively. The result shows that in total there were 19,869 visits to the website, or an average of 163 visits per day. There had been a nearly three-fold increase in total website traffic from 85.2 visits in September to 245.8 visits in December 2019. Safety hazard is the most frequently visited pages by tourists and there were 45 valid keywords found in the website panelboard. This study is the first to examine the possibility of developing a digital surveillance system using mobile phones directly involving travelers at destinations. Keywords: travel health, destination, mobile health, industrial revolution 4.0 |

INTRODUCTION

Background

Travelers are important populations from an epidemiological point of view because of high mobility, the possibility of getting a disease or accident outside the country of origin, the risk of exporting diseases to the destinations, and importing diseases into the country of origin (WHO, 2008). This causes several problems such as difficulties in measuring risk, due to the inability to determine the accurate number of travelers who have contracted a disease or accident (numerator) and the total number of travelers at risk (the denominator). The characteristics of travelers and the nature of the disease also create difficulties for monitoring and surveillance systems. Travelers who get the disease with a long incubation period generally return to their home country when symptoms appear thus surveillance problems in tourist destinations. Conversely, travelers who experience a disease with a short incubation period will have symptoms that have disappeared when returning to their country, hence surveillance problems in the country of origin (Wirawan, 2018).

In addition, several studies have shown that there is still a lack of travel health information received by international travelers (Wirawan et al.,

2020). Only about 18.3% of international travelers, especially those who visit friends and relatives, received pre-travel counseling, including getting the necessary travel vaccinations and chemoprophylaxis (Talbot et al., 2010). Considering the characteristics of the disease and travelers, the most relevant epidemiological data are the surveillance data on the travelers themselves. However, this is difficult to perform.

To date, only a limited number of travel health surveillance system has been developed in the destination country or tourist destinations. The development of mobile health technology has created opportunities to develop surveillance systems that can collect data from travelers themselves, provide travel health information specific to each tourist attraction, thus providing benefits to the country of origin and destination.

Research Objectives

This study aims to develop a system that allows tourists to obtain travel health information specifically in each tourist attraction, access the nearest health facility, and search any information about diseases, hazards and safety risks through a mobile phone. The feasibility of conducting digital surveillance through search histories and usage reports were assessed in this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Travel Health Surveillance

One of the most well-known travel health surveillance systems is the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. GeoSentinel was founded in Atlanta in July 1995 as a center for emerging infectious disease sentinels, for travel and tropical medicine, initially for US tourists but later expanded internationally (Freedman, Kozarsky and Weld, 1999). At present, this network involves 60 travel medicine clinics on 6 continents, and all clinics contribute to the supervision and monitoring of all travel-related diseases encountered at their locations. Collecting this data globally makes it possible to conduct a joint analysis of final diagnoses in populations traveling with similar geographical risk exposure. In addition, most of the GeoSentinel locations contribute to increased surveillance and networking with public health authorities. For example, members in Europe can also collaborate on EuroTravNet and members in Canada can participate in CanTravNet, both of which are initiatives from the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) in partnership with their respective public health authorities (ISTM, 2019). However, all of these systems use data from ill returned travelers, and have not yet provided http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

benefits for destination countries or tourist destinations in developing countries.

GeoSentinel does not yet have a participating location in Indonesia. This results in a lack of information about symptoms, risk factors, and diseases that have the potential to be applied to improve surveillance systems and public health in general. On the other hand, although it has a positive impact on the economy, an increase in the number of tourists is also accompanied by an increase in illness, accidents and deaths related to travel and tourism activities. It was estimated that almost half of the travelers to a developing country will experience health problems, and 8% will need medical attention (Reid, Keystone and Cossar, 2001).

Travel Health in Bali

The number of international travelers to Bali increased significantly in the last 10 years, from about 1.3 million in 2007 to approximately 5.7 million in 2017 (BPS, 2018). On the other hand, the current surveillance system does not yet include tourists as one of the target populations. Current data on diseases among tourists depends on reporting on health facilities and hospitals that provide services to tourists. There is currently no regular travel health surveillance to collect data from all clinics or hospitals that serve 170 e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

tourists. One effort related to this is a sporadic investigation into the area or tourist facilities when the authorities receive a case notification. Some cases have been reported such as Legionnaire's disease, fascioliasis, and diarrhea in tourists. Some disease surveillance exists and may include tourist data as populations at risk such as rabies, dengue fever, malaria, tuberculosis, Japanese encephalitis, hepatitis B, and HIV/AIDS (Informal communication with Bali Health Agency, 2019).

From the literature search results, very little is known about common diseases or symptoms that are specifically experienced by tourists to Indonesia and Bali in particular. This is because there is no robust and integrated travel health surveillance system that is able to include tourists in these destinations. The current surveillance system in Bali or Indonesia is generally only focused on routine diseases affecting the local population.

METHODOLOGY

The research began with the development of a progressive mobile website employing a research database which consists of hazards, risks and health facilities that have been geo-tagged and mapped based on their respective geographical positions in 197 tourist http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

attractions in Bali (Wirawan et al., 2017). An Android-based mobile application was made to provide more options for prospective users (international tourists).

Furthermore, the program or system was launched in 80 strategic tourist attractions in Bali at the end of August 2019, by putting on health promotion media in the form of banners, posters, table stands, and stickers. The outcome variables of this study are the level of system utilization and the frequency of travel health information received by tourists. Trends in some specific diseases, cases, hazards, and risks were observed monthly using a keyword analysis. Serial data for the first four months were analyzed and presented descriptively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

System Development and Launch

A progressive mobile website with the domain http://balitravelhealth.net/ has been launched at 80 strategic tourist attractions in Bali, under the name Bali Travel Health. In addition, an Androidbased mobile application has also been launched to improve user accessibility. The mobile application can be accessed via the following link:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details? id=com.balitravelhealth. A unique QR 171 e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

code was added in each health promotion medium to make it easier for tourists to access the website link, as seen by Figure 1.

Figure 1. QR code for promoting the Bali Travel Health website

The Bali Travel Health website and Android application display data on 197 tourist attractions in Bali, consisting of the following information:

-

• Potential hazards and safety risks at each tourist site

-

• Health facilities closest to each tourist attraction

-

• Common diseases found in Bali along with preventive measures that can be done by tourists

-

• A page for reporting new unregistered attractions, unregistered hazards, and relevant disease information not yet on the website

This media is a means to get information sourced from users (crowd sourced), especially to improve the sustainability and quality of existing information.

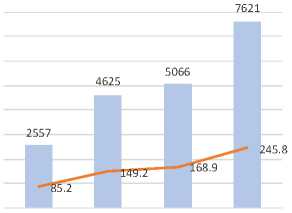

Usage Data

Based on the analysis of usage data, it can be seen an increase in access to the website as shown in Figure 2. In total, there were 19,869 visits to the website in the first four months, or an average of 163 visits per day. There has been a nearly three-fold increase in total website traffic from 2,557 visits in September to 7,621 visits at the end of December 2019. In other words, average visits per day increased from 85.2 in September to 245.8 in December 2019. This indicates that the promotion media have effectively attracted tourists to access the website.

9000

900.0

8000

7000

6000

5000

2000

1000

0

c 4000

O

S 3000

800.0

700.0

600.0 ro

500.0

400.0

300.0

200.0

100.0

0.0

September October November December

■■■ Monthly ^^^^^*Average per day

Source: Website usage statistics (primary data)

-

Figure 2. Monthly and average per day visit of the website in 2019.

Furthermore, we analyzed usage data for 13 specific pages containing information on diseases, health, and safety hazards.

\

Table 1. Data usage for specific pages in the first four months

|

Web Page |

Frequenc y |

Proportion (%) |

|

Vaccinations |

35 |

4.4 |

|

Safety | ||

|

Hazards |

115 |

14.6 |

|

Methanol |

74 |

9.4 |

|

Scuba Diving |

40 |

5.1 |

|

Climates |

56 |

7.1 |

|

Bites or | ||

|

Stings |

59 |

7.5 |

|

STIs |

31 |

3.9 |

|

JE |

68 |

8.6 |

|

Diarrhoea |

39 |

4.9 |

|

Rabies |

56 |

7.1 |

|

Dengue |

72 |

9.1 |

|

Ergonomic |

98 |

12.4 |

|

Violence |

47 |

5.9 |

|

Total |

790 |

100.0 |

JE: Japanese Encephalitis; STIs: Sexually

Transmitted Infections

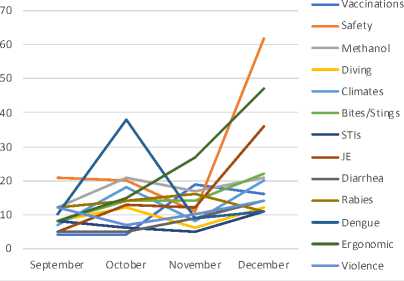

Table 1 indicates that in the first four months, safety hazard is the most frequently visited pages by tourists, followed by ergonomic hazards, methanol poisoning, dengue and Japanese encephalitis. Safety hazards at tourism attractions generally include any unsafe conditions that can cause injury, illness, and death, such as slips, trips, and falls; sharp objects; and difficult access or pathway (Wirawan et al., 2017). The trend for each month was presented in Figure 3, to provide understanding on the dynamic of the specific web page usage.

Source: Website usage statistics (primary

data)

-

Figure 3. Monthly visit to the specific web pages on disease, health, and safety in 2019.

Figure 3 demonstrates the trends in the number of visits for each specific web page from September to December 2019. Each month, the most frequently web pages accessed may be analyzed to provide important information on what issues the travelers needed the most. For instance, information on safety hazards was consistently accessed during the first four months. The number of visits for the web page on dengue was much higher than other pages in October 2019, indicating that this disease might be of concern. Access to the methanol poisoning page was consistently moderate during the first four months after the launch of the website. While the access to the page on Japanese encephalitis was notably higher in December 2019 compared to the previous three months. These descriptive analyses are some of the

examples on how possibly use this data for surveillance or monitoring.

In addition, search histories recorded on the website may also indicate the need of the travelers about some important information required by them. Analyzing its trend might be useful as well for the digital surveillance measures in the long term.

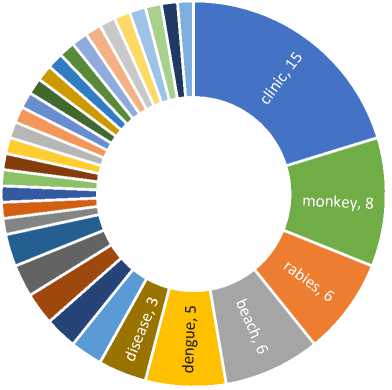

Source: Website usage statistics (primary data)

-

Figure 4. Keyword analysis from search histories in the first four months.

Between September and December 2019 there were 45 valid keywords found in the website panelboard. Figure 4 illustrates the main keywords used by users, after some relevant and similar keywords were merged. The keyword “monkey” consists of some similar keywords including monkey, bites, scratches, monkey bite(s), monkey scratch(es). The most used keywords were “clinic(s)”, indicating the users need of

knowing the surrounding health facilities. Some endemic diseases currently in Bali such as dengue and rabies were among top keywords used by the tourists. Other keywords which amount two or less are beaches, temple, waterfall, JE, vaccination, malaria, and several tourist attractions.

This study is the first to examine the possibility of developing a digital eillance system using a mobile phone ctly involving travelers at destination. results of the first four months of data ysis since the system was launched, w that this initial data is very mising to be used to complement the ting surveillance system. Its use in the run will provide big data that can be zed for programs in real time (Nsoesie et al., 2015). In addition, crowed sourced data resulting from the use of the system by travelers in the future can provide an indication of the needs of tourists, and the possibility of an increase in cases of travel-related disease in certain geographical areas.

This system can be used as a feeder to make a more integrated system by involving health facilities in tourist attractions (World Health Organization, 2019). The combination of digital surveillance with regular surveillance involving travel health facilities will help the local health department to monitor

diseases, possible local outbreaks, and even an emerging disease, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 or known as COVID-19 (Wu and McGoogan, 2020). From this study however, there is no indication that travelers visiting Bali between September and December 2019 experienced one or more of the COVID-19 symptoms, as shown by the keyword analysis in Figure 4.

CONCLUSION

A progressive mobile website and an Android-based mobile application for Bali Travel Health have been launched at 80 strategic points at tourist attractions in Bali. There had been an increase in website access in the first four months, with an average visit of 163 per day. There had been a change in trends from the types of information accessed by users, where safety hazard had been the page that had been consistently accessed in the first four months. An increase in both the number and variety of keywords used had also consistently appeared in the first four months.

This preliminary study provides evidence that a digital surveillance system has a potential to be implemented at destinations. Its integration with regular surveillance system involving travel health facilities will improve the provision http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

of data on travel-related disease, accidents, and risks.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Bali

Province Health Agency, Bali Province Tourism Agency, and Bali Tourism Board for their assistance and formal supports to this study.

REFERENCES

BPS (2018) International Travelers to Indonesia by Arrival Gate, 19972017, Statistics Indonesia. Available at: https://www.bps.go.id/statictable/20 09/04/14/1387/jumlah-kunjungan-wisatawan-mancanegara-ke-indonesia-menurut-pintu-masuk-1997-2017.html (Accessed: 11

March 2019).

Freedman, D., Kozarsky, P. E. and Weld, L. H. (1999) ‘GeoSentinel: The Global Emerging Infections Sentinel Network of the International Society of Travel Medicine’, Journal of Travel Medicine, 6(2), pp. 94–98.

ISTM (2019) GeoSentinel. Available at: http://www.istm.org/geosentinel (Accessed: 28 March 2019).

Nsoesie, E. O. et al. (2015) ‘New digital technologies for the surveillance of infectious diseases at mass gathering events’, Clinical Microbiology and Infection. Elsevier Ltd, 21(2), pp. 134–140. doi:

10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.017.

Reid, D., Keystone, J. S. and Cossar, J. H. (2001) ‘Health Risks Abroad: General Considerations’, in DuPont, H. L. and Steffen, R. (eds) Textbook of Travel Medicine and Health. 2nd edn. Hamilton, London: B.C Decker Inc., pp. 3–9.

Talbot, E. A. et al. (2010) ‘Travel medicine research priorities: establishing an evidence base.’, Journal of Travel Medicine, 17(6), pp. 410–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00466.x.

WHO (2008) International Health Regulations 2005. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wirawan, I. M. A. et al. (2017) Kesehatan dan Keselamatan Wisata: Direktori Hazard, Risiko, dan Layanan Kesehatan Wisata di Bali. 1st edn. Yogyakarta: Andi Publishing.

Wirawan, I. M. A. (2018) ‘Healthy tourism initiatives at destinations: opportunities and challenges’, Public Health and Preventive Medicine Archive, 6(1), pp. 1–3. doi:

10.15562/phpma.v6i1.1.

Wirawan, I. M. A. et al. (2020) ‘Travel agent and tour guide perceptions on travel health promotion in Bali.’, Health Promotion International,

35(1), pp. e43–e50. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day119.

World Health Organization (2019) WHO guideline: recommendations on

digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva:

World Health Organization.

Wu, Z. and McGoogan, J. M. (2020) ‘Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China’, JAMA, 323(13), p. 1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

176

e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback