NATIONAL ANTHEM SINGING AT INTERNATIONAL SPORT COMPETITIONS: DOES THE DISCOURSE AGAINST KIMI GA YO AFFECT THE JAPANESE YOUTHS?

on

E-Journal of Cultural Studies

DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015)

ISSN 2338-2449

May 2023 Vol. 16, Number 2, Page 52-64

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

NATIONAL ANTHEM SINGING AT INTERNATIONAL SPORT COMPETITIONS: DOES THE DISCOURSE AGAINST KIMI GA YO AFFECT THE JAPANESE YOUTHS?

Kumiko Shishido1, I Nyoman Suarka2, I Nyoman Dhana3

1Mahasaraswati University, Denpasar, 2,3Cultural Studies Study Program, Faculty of Arts, Udayana University

Email: 1kumikoshishido@gmail.com, 2nyoman_suarka@unud.ac.id, 3nyomandhana@ymail.com

Received Date : 14-01-2023

Accepted Date : 26-03-2023

Published Date : 31-05-2023

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to discuss the view of Japanese youths on the discourse against Kimi ga Yo, especially in the setting of international sport competitions. It is a qualitative-research that uses the open model survey technique to obtain the primary data from the Japanese youths aged 20 to 22. The result of this paper shows that the discourse against Kimi ga Yo does not implicate towards the youths’ view in the present days of Japan. It also highlights the youths’ ignorance on the literal meaning of the lyrics and their emphasis on the function of Kimi ga Yo as a national anthem.

Keywords: Kimi ga Yo, critical discourse analysis, Japanese youths

INTRODUCTION

National anthem (Japanese terms: ‘kokka’) refers to the song that represents a country –or the people of such country– being played in occasions such as in national ceremony or international event (Matsumura, 1995: 976). Kimi ga Yo, Japanese national anthem which also happens to be the shortest national anthem (Takiguchi, 2020), was formalized by the Japanese Government through the 1999 Law on the National Flag and National Anthem (JapanGov, 2021). Despite the absence of information on the ‘waka’ or traditional Japanese poetry from which the lyrics of Kimi ga Yo were originally derived (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2020: 2), it can be known that this anthem sparked bitter controversies among the Japanese society. The refusal against Kimi ga Yo was

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

rooted in a discourse that this anthem represents both militarism and imperialism during the World War era with the lyrics praising the long reign of the emperor (Hirata, 2009). It was particularly centered in the academic field, i.e., among Japanese teachers who refused to sing Kimi ga Yo at school ceremonies such as on graduation day (Marshall, 2012).

In the contemporary era, one of many occasions where national anthem is played or sang is at international sport competitions (Slater, et.al, 2018: 1). In such setting, there is a universal practice where each of the competing teams will be given the chance to sing their national anthem before a match. According to Hoberman (in Aji, et.al., 2018: 39), sport became a mass psychology phenomenon related to nationalism; particularly as the characteristic of one’s nation is defined through the raising of its national flag and the singing of its national anthem. This statement is consistent with the notion that national anthem produces the national identity of a country (Rudiyanto, 2016: 8). As there was no any kind of written agreement between nations on such practice at international sport competitions, historians tend to refer its commencement to one particular event: the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the baseball match between Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs at the 1918 World Series (Bologna, 2018).

Just as other countries, Japan who actively participates in international sport competition also complies to the practice by singing Kimi ga Yo before team match. However, it can be found that the singing of Kimi ga Yo at international sport competition portrays a different situation unlike among academics. This is mainly shown by the absence of controversial reports or protest –neither from the athletes nor the audience– against the kokka. As an example, the recognition and respect towards Kimi ga Yo at international sport competition can be seen in the below clips picturing the emotional singing of Kimi ga Yo at the 2019 Rugby World Cup.

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

(Source: World Rugby Official YouTube Account, 2019)

The refusal against Kimi ga Yo in academic setting can accordingly be linked to the variative contexts surrounding the discourse. Despite the absence of information on the concrete form of such discourse – whether it was spoken or written– its impact among the Japanese can be considered alarming at the time. One of the most fatal impacts was the suicide of Toshihiro Ishikawa, the principal of Sera Highschool in Hiroshima who was unable to handle the teachers’ refusal to sing Kimi ga Yo at the graduation day, as for them it was equal to praising the emperor who let the atomic bomb dropped in Hiroshima (Newsweek, 1999). Although the controversy surrounding Kimi ga Yo was peaking around the era of its formalization, the refusal can still be found afterwards, including in the case of a parent who refused to sing the anthem at his daughter’s school ceremony and a teacher who spread the words on her refusal against the anthem, as shown in the clips below.

E-Journal of Cultural Studies

DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015)

ISSN 2338-2449 https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

In the view of critical discourse analysis, language is not only analyzed from its linguistic elements, rather it is strongly linked to the context relating to the certain aim and practice of the discourse itself (Badara, 2012: 26 & 28). According to Van Dijk, Fairclough and Wodak (in Badara, 2012: 29-35), critical discourse analysis highlights five elements as its characteristics, one of which is context. As the core point of discourse analysis is to portray how text and context co-exist in a communication process, context encompasses all situations outside the text which affect the use of language, including the social setting surrounding it (Badara, 2012: 30-31).

This paper aims to discuss the view of Japanese youths on the discourse against Kimi ga Yo in the present days of Japan, particularly by underlining the contrast impact between the two different settings. Moreover, the analysis in this paper will be focused on how the youths see the discourse in their-era-of- Japan, both as the Japanese who were recently engaged in academic fields and the millennials who are familiar with international sport competitions. Additionally, this paper will also highlight whether the youths prefer to criticize the lyrics of Kimi ga Yo to fully comprehend the meaning behind the anthem or to focus on its function without putting much attention to the lyrics and its meaning.

METHOD

As a qualitative-research, the method used in this paper tends to be descriptive and naturalistic, where the findings would be casuistic and would not be aimed to be generalized into the other context (Irawan, 2006: 52). This paper uses the primary data derived from Japanese youths (age 20 to 22) who are spread all across Japan. The technic used to obtain the data is survey technic which is commonly used to comprehend the behavior and opinion of a certain group of people (Maryaeni, 2008: 67). In particular, it uses the open-model survey to highlight each opinion and perspective of the youths qualitatively.

E-Journal of Cultural Studies DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015) ISSN 2338-2449 https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

RESULT AND DISCUSSIONS

Factors Underlying the Different View of “National Anthem Singing” at School and at International Sport Competitions

From the question raised to find out the underlying factors on the different views resulted from the same song, this paper presents the below data analysis.

Data 1

「スポーツの現場では国の代表という側面があるが学校ではそれが感じられないからだと思います。

」

“Supōtsu no genba de wa kuni no daihyō to iu sokumen ga aru ga gakkōde wa sore ga kanji rarenai kara da to omoimasu.”

“I think it’s because in sports setting, there is an aspect of ‘country’s representation’ which cannot be felt in school.”

The above data shows a youth’s view which emphasizes on the aspect of ‘country’s representation’, as both the athletes and the audience in international sport competitions are competing against another country. In this sense, such aspect would only occur when another country or another external party is involved in the setting. The singing of Kimi ga Yo before sports competition can also be seen as a platform to channel expressions, emotions and hopes towards the country representative team. Whereas at school, the singing of Kimi ga Yo which is done internally does not involve any sense of representing Japan.

This view can be linked to the notion of Haryatmoko (2019: 5) that discourse is a social practice in the form of symbolic interactions and how the language is used to aim particular social objectives, including to generate social changes. In this sense, the aim to generate social changes iniciated by the teachers who refused to sing Kimi ga Yo appear to be inapplicabe in the setting of international sport competitions, as representing the country and competing for its glory is seen as a bigger aim of the surrounding social setting. Consequently, the involvement of another country affects the sense of belonging towards one’s own country, while its absence also affects the sense of belonging in a reverse way.

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

E-Journal of Cultural Studies DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015) ISSN 2338-2449 https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

Data 2

「背負っているものの大きさ。 ( 学校現場の教員や児童生徒に比べ、アスリートはより 「代表として国を背負っている」という部分が強調されやすいように感じる)」

“Shotte irumonono ōki-sa. (Gakkō genba no kyōin ya jidō seito ni kurabe, asurīto wa yori ‘daihyō to shite kuni o shotte iru' to iu bubun ga kyōchō sa re yasui yō ni kanjiru)” “It is the size of what they carry. (I feel like the sense that they carry their own country on their shoulder as representatives is more emphasized for athletes at sports field than teachers and students at school)”

The emphasis of the above data is on the size or scale of the responsibility carried at each event. In international sports competitions, the athletes particularly carry the professional responsibility to perform their best to win against another country. Similar with the previous data, this view shows how the aspect of being the country’s representative affects the invalidity of the discourse. The particular view that academics carry less responsibility as country representative compared to athletes, however, cannot be generalized into a notion, but can be linked to the notion of Widja (2012: 152) that education reflects the praxis of cultural life to disclose the cultural ideological traps of contemporary cultural practices rooted in the past. Hence, there is a clear difference on the focus and aims of the teachers through the education and the athlethes through the competition.

Data 3

「その時々の心情や環境(場所)」

“Sonotokidoki no shinjō ya kankyō (basho)”

“It depends on the atmosphere and the environment (the place) at that time”

Unlike the first and the second data, this data presents a more general view which essentially states how context takes part in the influence of critical discourse analysis. This is consistent with the notion that a text or a written discourse depends on the readers or audience as a crucial part who makes the text itself works (Ida, 2014: 8), while its meaning is also inseparable from the situational context (Lubis, 2014: 103). As the ‘context’ encompasses all situations outside the text (Badara, 2012: 30-31), it can be underlined that the atmosphere and environment at the venue of international sport competitions affects the invalidity of the discourse. In this sense, international sport competitions are commonly held in a festive atmosphere while the academic and formal atmosphere at school ceremonies tends to trigger the discourse.

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

Data 4

「スポーツは国の代表という象徴的なもの。それに対し学校での国家斉唱は形式的なもの。」 “Supōtsu wa kuni no daihyō to iu shōchō-tekina mono. Sore ni taishi gakkō de no kokka seishō wa keishiki-tekina mono.”

“Sport is a symbolic thing that represents a country. On the other hand, the national anthem sang at school is a formality.”

The above data shows a youth’s view which re-emphasizes the symbolic aspect of Kimi ga Yo at international sports competitions. In this sense, ‘symbol’ can be equalized to identity, whereas the singing of Kimi ga Yo at school is seen as a formal gesture that is not or less emotionally attached to the audience. As it is stated earlier that national anthem produces the national identity of a country (Rudiyanto, 2016: 8), this view may reflect that the teachers who refused to sing of Kimi ga Yo at school did not see the anthem as their identity. The discourse against Kimi ga Yo, then, was spread as part of the hegemony where the dominant group (discourse producers –in this context, the teachers–) imposes the consent of the dominated groups (discourse audience) by articulating a political and ideological vision which claims to speak for all (Gramsci in Edkins and Williams, 2010: 234).

Japanese Youths’ View on the Urge to Criticize the Lyrics and Meaning of Kimi

ga Yo as Their National Anthem

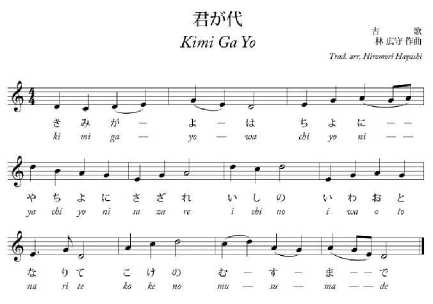

May your reign

Continue for a thousand, eight thousand generations, Until the tiny pebbles Grow into massive boulders

Lush with moss

(English translation by Hood, 2001: 166.)

Subsequently, from the question raised to find out whether the youths prefer to criticize

E-Journal of Cultural Studies DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015) ISSN 2338-2449 https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

the lyrics of Kimi ga Yo or not, this paper presents the below data analysis.

Data 5

「機能 国歌という大義は意味以上に大きい」

“Kinō – Kokka to iu taigi wa imi ijō ni ōkī”

“The fuction – the meaning behind the existence of national anthem itself is bigger than the meaning of its lyrics.”

The above view shows that the function of Kimi ga Yo as national anthem is more important than the meaning of its lyrics. In this sense, the respondent sees how the representation of Japan’s national identity through its kokka carries a bigger meaning compared to the discourse against the kokka that its lyrics are problematic. Such view particularly sees the nationalism value through the kokka, where nationalism itself refers to an ideology with the sense of belonging and sense of serving a national community as its affective driving force (Eatwell and Wright, 2004: 212).

Data 6

「国歌としての機能に重点を置いて考える

理由: 歌詞に興味がないから 」

“Kokka to shite no kinō ni jūten o oite kangaeru. Riyū: Kashi ni kyōmi ga naikara” “To sing it by focusing on its function, because I do not care of the literal meaning of the lyrics.”

This view shows a particular apathy on the meaning of Kimi ga Yo’s lyrics, as the respondent does not care nor have any interest towards the lyrics meaning. This view can be attributed to the notion that the Japanese tend not to attach themselves into a strict and particular ideology, where they then prefer to have a flexible ethics (Benedict, 1946 in Hasegawa, 2005: 373). Ideology itself can no longer be seen to exist vertically as in the supra-structure and sub-structure relation –for example, a nation and its people–, it can rather grow unconsciously in a human-to-human relationship on a daily basis (Althuser in Takwin, 2009: 85). Hence, it can be seen that a particular discourse and ideology against Kimi ga Yo that was once peaking in Japan does not implicate to the respondent’s view, as the respondent may not want to be attached to a strict ideology and/or has a personal ideology towards the issue in question.

Data 7

「自分は国歌としての機能を重視するべきだと思います。理由は今の日本の若者は恐らく「

E-Journal of Cultural Studies

DOAJ Indexed (Since 14 Sep 2015)

ISSN 2338-2449 https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

君が代」に 対して関心が無く歌詞の意味も良く知らずに歌っている人が大半で、少なからず 歌詞の意味にその人が 左右される事はないと思ったからです。」

“Jibun wa kokka to shite no kinō o jūshi suru beki da to omoimasu. Riyū wa ima no Nihon no wakamono wa osoraku `Kimigayo' ni taishite kanshin ga naku kashi no imi mo yoku shirazu ni utatte iru hito ga taihan de, sukunakarazu kashi no imi ni sono hito ga sayū sa reru koto wa nai to omottakaradesu.”

“To me, we should rather emphasize on its function as the national anthem, since the majority of Japanese youths do not have an interest in Kimi ga Yo nowadays. They tend to sing it without comprehending the lyrics so no one is affected by the meaning of its lyrics.”

Similar to the previous two, this view also stresses on the apathy of the majority of Japanese youths nowadays. Moreover, the particular view stating that “no one is affected by the meaning of its lyrics” shows how the youths prioritize the avoidance of conflict by choosing not to comprehend the actual meaning behind the lyrics or involving themselves in the discourse. This view can also be linked to the flexible ethics of the Japanese (Benedict, 1946 in Hasegawa, 2005: 373) where they may not see the existence of Kimi ga Yo as something worth criticizing.

Data 8

「国歌の機能を重視すべき

理由: 君が代の歌詞は現代日本語とは異なり、私自身歌詞の意味をよく理解していないから。」 “Kokka no kinō o jūshi subeki. Riyū: Kimigayo no kashi wa gendai nihongo to wa kotonari, watakushi jishin kashi no imi o yoku rikai shite inai kara.”

“We should prioritize its function as the national anthem. Reason: the language used in the lyrics of Kimiga Yo is an ancient language and is different from the present Japanese, thus I do not really comprehend the lyrics myself.”

Lastly, this view also emphasizes on the function of Kimi ga Yo as Japan’s kokka. However, it tends to underline the linguistic aspect where the waka from which the lyrics were derived is an ancient language which does not meet the present days use of the Japanese language. Thus, this view sees that the ancient lyrics should not be subject to debate or discourse as the youths would not comprehend the lyrics either. In this sense, the discourse against the lyrics of Kimi ga Yo itself may raise a question as the translation of the ancient waka can be subject to multiple interpretations. Thus, it can further be linked

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

to the notion that the rules created by the power holders (or the discourse producers) are “the truth games” (Foucault in Lubis, 2014: 22); meaning that while the true meaning of Kimi ga Yo’s ancient lyrics is still subject to multiple interpretations, the discourse was spread heavily among the academics in the era of its formalization.

CONCLUSION

From the first question, it can be inferred that the underlying factors that distinguish the view towards Kimi ga Yo are mainly centered in the aspect of ‘country’s representation’ which includes certain duties and responsibilities, as well as whether the anthem is seen as the Japanese identity or not. Moreover, nowadays Japanese youths tend to emphasize on the importance of Kimi ga Yo as their kokka without the urgency to criticize the meaning of its ancient lyrics. Such views can mainly be attributed to the flexible ethics of the Japanese and their apathy on the meaning of the lyrics. These findings eventually show that the discourse against the problematic lyrics of Kimi ga Yo that was once peaking among the academics no longer shows a relevancy in the view of the nowadays youths, as it does not implicate on their views as the discourse audience.

REFERENCES

Aji, R. N. B., et.al. (2018). National Anthem and Nationalism in Football. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 226: 39-42.

Badara, Aris. 2012. Analisis Wacana: Teori, Metode, dan Penerapannya pada Wacana Media. Jakarta: Kencana.

Bologna, Caroline. 2019. The History of The National Anthem In Sports (online), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/history-national-anthem-

sports_n_5afc9bcfe4b06a3fb50d5056, accessed on 20 April 2021.

Eatwell, Roger and Wright, Anthony (ed.). 2004. Ideologi Politik Kontemporer. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Jendela.

FRANCE 24 English. 2008. Patriotism in Japanese schools breeds controversy (online), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmCAnyt4aaA, accessed on 3 March 2021.

Haryatmoko. 2019. Critical Discourse Analysis (Analisis Wacana Kritis): Landasan Teori, Metodologi dan Penerapan. Jakarta: Rajawali Pers.

Hasegawa, Matsuji. 2005. Kiku to Katana: Nihon Bunka no Kata (Japanese translation of Benedict, Ruth.

1946. The Chrysanthemum and The Sword—Patterns of Japanese Cuture). Tokyo: Kodansha.

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

Hirata, Keiko. 2009. Japanese anthem controversy reflects broader cultural battle over nation’s past (online), https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2009/04/japanese-anthem-controversy-reflects/#:~:text=Kimigayo%20and%20Hinomaru%20have%20long,honor%20th e%20emperor's %20long%20rein., accessed on 3 March 2021.

Hood, Christopher. 2001. Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Ida, Rachmah. 2014. Metode Penelitian Studi Media dan Kajian Budaya. Jakarta: Kencana.

Irawan, Prasetya. 2006. Penelitian Kualitatif & Kuantitatif Untuk Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial. Jakarta: Department of Administrative Science. Faculty of Social and Political Sciences. University of Indonesia.

Lubis, A. Y. 2014. Teori dan Metodologi Ilmu Pengetahuan Sosial Budaya Kontemporer. Jakarta: PT RajaGrafindo Persada.

Marshall, Alex. 2012. Why should Japan's teachers have to sing the national anthem? (online), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/oct/20/no-harmony-singing-japan-national- anthem, accessed on 6 March 2021.

Maryaeni. 2008. Metode Penelitian Kebudayaan. Jakarta: PT Bumi Aksara. Matsumura, Akira. 1995. Daijisen. Tokyo: Shogakkan.

Newsweek Staff. 1999. When A Flag Is Not A Flag (online), https://www.newsweek.com/when-flag- not-flag-163766, accessed on 3 March 2021.

Rudiyanto, Arief. 2016. Studi Analisis tentang Nilai-Nilai Kebangsaan dalam Lagu Kebangsaan Indonesia Raya (Undergraduate Thesis). Semarang: Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Semarang.

Slater, M. J., et.al. (2018). Singing it for “us”: Team passion displayed during national anthems is associated with subsequent success. European Journal of Sport Science, 1-9.

Takiguchi, Takahiro. 2020. Did you know?: Japan’s national anthem Kimigayo (online), https://japan.stripes.com/node/40487, accessed on 3 March 2021.

Takwin, Bagus. 2009. Akar-akar Ideologi: “Pengantar Kajian Konsep Ideologi dari Plato hingga Bourdieu”. Yogyakarta & Bandung: Jalasutra.

The Government of Japan. National Flag and Anthem (online), https://www.japan.go.jp/japan/flagandanthem/, accessed on 3 March 2021.

Utomo, T. W. 2010. Teori-teori Kritis: Menentang Paradigma Utama Studi Politik Internasional (Indonesian translation of Edkins, Jenny and Williams, N. V. 2009. Critical Theorists and International Relations). Yogyakarta-Surabaya: Pustaka Baca.

Widja, I. G. 2012. Pendidikan Sebagai Ideologi Budaya: Mengamati Permasalahan

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ecs/

Pendidikan Melalui Pendekatan Kajian Budaya. Denpasar: Master and Doctoral Programme of Cultural Studies of Udayana University, in association with Sari Kahyangan Indonesia.

World Rugby. 2019. Passionate Japanese anthem v Scotland (online), https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=p0xjv_Jtfyc, accessed on 3 March 2021.

64

Discussion and feedback