Total Genomic DNA Extraction Studies from Seaweeds

on

Advances in Tropical Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences 4(1): 10-14, February, 2020 e-ISSN:2622-0628

DOI: 10.24843/ATBES.2020.v04.i01.p03 Available online at: https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/ATBES/article/view/58096

10

Total Genomic DNA Extraction Studies from Seaweeds

Wildan Mujahidul Basyar, Made Pharmawati*, Ida Ayu Astarini

Biology Study Program, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Udayana University Jl. Kampus Unud Bukit Jimbaran, Badung-80361, Bali, Indonesia *Corresponding author: made_pharmawati@unud.ac.id

Abstract. One of marine resources that has high value is seaweed. Seaweed is a carrageenan producer used in the food industry. Seaweed contains many minerals, vitamins and proteins that are useful for health. Carotenoids are pigments found in seaweed that function as antioxidants. The genes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis have been studied and provide opportunities for genetic improvement of seaweed. DNA is a basic requirement in molecular analysis. Therefore, a suitable method of DNA extraction from seaweed is needed. The aim of this research was to investigate DNA extraction method from several seaweed species and test the DNA quality through PCR-RAPD. Seaweed samples were collected from Pantai Bumi Perkemahan Taman Nasional Bali Barat and DNA was extracted using Doyle and Doyle’s method with modifications. PCR-RAPD was conducted using primer UBC127 and OPD 11 to test the quality of DNA. Results showed that 3 hours incubation in 60ºC had the best result of DNA extraction. However, the quality of DNA was low, as indicated by inconsistent PCR-RAPD products. Further optimization in DNA extraction is needed to obtain high quality DNA for genetic analysis.

Keywords: DNA; seaweed; quality; PCR-RAPD

-

I. INTRODUCTION

Bali has a variety of coastal and marine ecosystems such as mangroves, corals and seaweed that have important values such as for food and medicine. Development of marine resources into a source of medicines, is important for both the development of science and economic.

Market demand for natural ingredients as a source of food and medicine is increasing rapidly [1]. One of the ingredients that is currently very popular in the market is carotenoids. Carotenoids are fat-soluble pigments, which are a group of yellow, orange, red and brown pigments found in various organisms such as: phytoplankton, seaweed, bacteria and certain plants. Humans and animals consume carotenoids to meet the needs in their bodies as antioxidants and are very dependent on external supplies [2].

Currently, carotenoids are produced on an industrial scale synthetically using chemicals. This synthetic carotenoid has the disadvantage of being a stereoisomer not found in natural carotenoids [3]. In addition, contamination can occur with reaction intermediates and contain less nutrients [3]. Therefore, there is an opportunity for carotenoid production from natural sources. One natural resource that has not been much explored is seaweed.

All seaweed produces carotenoids. The genes responsible for carotenoid biosynthesis (Crt gene groups) have been characterized [4, 5]. The discovery of these genes provides an opportunity to engineer the biosynthesis pathway of astaxanthin and other carotenoids in order to produce various carotenoids from various types of

seaweed that have the potential to produce higher carotenoid production [5].

Genetic engineering and other genetic analyses require DNA as material in research. Therefore, suitable DNA extraction technique from seaweed that can produce DNA with good quality and quantity is needed.

Methods of DNA extraction should be quick, reproducible and free from contamination. The quality of DNA determines the success of DNA analysis through amplification or digestion. The presence of contaminant can reduce amplification efficiency [6]. Several methods can be used to test the quality of DNA. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one method that is used to confirm the DNA quality.

The aim of this research was to investigate DNA extraction method from several seaweed species and test DNA quality through PCR-RAPD.

-

II. RESEARCH METHODS

Sample Collection

Sampling was carried out at Pantai Bumi Perkemahan Taman Nasional Bali Barat. Seaweed samples collected were Ulva reticulata, Ulva lactuca, Turbinaria sp., Gracilaria sp., Sargassum sp., Laurencia sp., Padina sp., Halimeda sp 1, Halimeda opuntia, Amphiroa sp. (Fig. 1). Samples were taken by hand in intertidal areas during low tide. Identification was done based on morphology using several references [7, 8].

Seaweeds were dried on newspaper and air dried without sunlight. After that the dried seaweeds were cut

with scissors until it was small then blended to form fine seaweed powder.

Fig. 1. Seaweed species collected from Pantai Bumi Perkemahan Taman Nasional Bali Barat. a. Gracilaria sp., b. Turbinaria sp., c. Padina sp,, d. Sargassum sp., e. Ulva reticulata, f. U. lactuca, g. H. macroloba, h. H. opuntia, i. Laurencia sp., j. Amphiroa sp.

Seaweed DNA Extraction

DNA extraction was carried out based on the Doyle and Doyle [9] method by modifying the incubation time in the extraction buffer. As much as 0.1 gr of fine blended seaweed powder was incubated at 65ºC in 1 ml of DNA extraction buffer (2% CTAB, 1.4 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris pH 8 added 1% β mercaptoethanol and 1 % PVP) for 1 hour (the mixture was mixed every five minutes). Centrifugation was done at a rotating speed of 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and then a mixture of phenol: chloroform: isoamylalcohol (25: 24: 1) with the same volume was added. Centrifugation at a rotational speed of 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes was conducted. The supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube then a chloroform: isoamylalcohol (24: 1) mixture was added in the same volume as the supernatant. The mixture was then

centrifuged at a rotational speed of 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

The resulting supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube then cold isopropanol was added 2 times the supernatant volume and incubated at cold temperature (-20ºC) for 30 minutes. Subsequently centrifuged 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes and the supernatant removed. The resulting pellet was washed with 70% ethanol then centrifuged at a rotational speed of 10,000 rpm for 4 minutes. Washing liquid was then discarded and the pellets were dried and then added by 100 µl of sterile water.

In the second modification, the sample used was 0.1 gr of fine powder of seaweed and incubated at 65ºC in 1.5 ml of DNA extraction buffer for 2 hours. The third modification method was carried out using a sample of 0.1 g of fine powder of seaweed and incubated at 65ºC in 2 ml of DNA extraction buffer for 3 hours.

PCR-RAPD

In this study, 2 RAPD primers (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) were used. The primers were UBC127 (5’-ATCTGGCAGC-3’) and OPD11 (5’-ACGGCCATTG-3’).

PCR reactions with UBC127 and OPD11 primers were carried out at a total volume of 20 µl containing a mixture: 1X polymerase buffer, 4.5mM MgCl2, 0.25mM dNTP, 1x Taq DNA polymerase, 3M primers and 15 ng DNA, 5% glycerol and the remaining sterile water up to a volume of 20 µl. The PCR programs used were: initial denaturation at 94ºC for 5 minutes with one cycle, denaturation at 94ºC for 1 minute, annealing at 36ºC for 1 minutes, elongation at 72ºC for 2 minutes with 40 times cycles and the final elongation was done at 72ºC for 7 minutes for one cycle.

Electrophoresis of DNA and PCR Product

In electrophoresis of total seaweed DNA extraction, 0.8% agarose was used for visualization, while for PCR product, 1% agarose in 1X TAE (40mM Tris-acetate pH 7.9 and 2mM Na2EDTA) was used. DNA samples were mixed with loading blue with a ratio of 5 µl DNA samples were added 1 µl loading blue, then put in a gel well and electrified 100 volts for 30 minutes. Staining was done by soaking the gel in ethidium bromide for 30 minutes. DNA observation was carried out using a UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad Mini) and a photo shoot was taken.

-

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

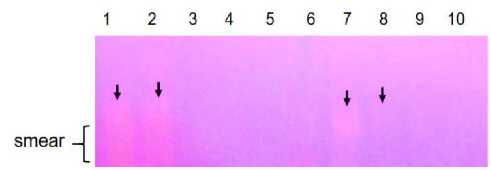

Extraction with an incubation time of 1 hour showed DNA bands on U. reticulata and H. opuntia. DNA bands with smears were observed on Sargassum sp. and Padina sp, while in Turbinaria sp., Gracilaria sp., H. opuntia, Amphiroa sp. and H. macroloba, no DNA band was observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. DNA extraction results from several seaweed species with 1 hour incubation in CTAB buffer. 1. Sargassum sp., 2. Padina sp., 3-5. Turbinaria sp., 6. Gracilaria sp., 7. U. reticulate, 8. H. opuntia, 9. Amphiroa sp., 10. H. macroloba. Arrows indicate DNA bands.

and 8). Therefore, electrophoresis was repeated and 10 µl DNA from each species was loaded. Result from the electrophoresis was shown in Figure 4.

In DNA extraction with 1 hour incubation, DNA was not extracted successfully in several samples such as Turbinaria sp., Gracilaria sp., Amphiroa sp. And H. macroloba. This can be due to the lack of extraction buffer volume and lack of incubation time in this sample so that the buffer is less optimal in lyse the cell walls and membranes. According to Jain [10] a longer incubation period in lysis buffer increases the exposure of the cells to the lysis buffer which lead to a more complete cell lysis. Besides that, according to Rogers and Bendich [11], the use of a buffer in a small volume (1 ml) is unable to separate proteins and polysaccharides so that it contaminates the results of isolation.

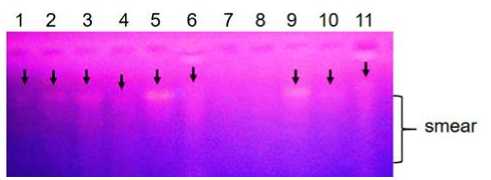

Extraction by modifying the incubation period for 2 hours produced DNA that is clearly visible in several species of seaweed such as Sargassum sp., H. opuntia, and H. macroloba (Fig. 3). Extraction by incubation for 3 hours produced DNA in Sargassum sp., Ulva lactuca, Ulva reticulata, Gracilaria sp. and Amphiroa sp. as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The results of DNA extraction from several species of seaweed with incubation of 2 hours (1-4) and 3 hours (5-11). 1. Sargassum sp., 2. H. opuntia, 3-4. H. macroloba, 5. Sargassum sp., 6. U. lactuca. 7. Laurencia sp., 8. Turbinaria sp., 9. U. reticulate, 10. Gracilaria sp., 11. Amphiroa sp. Arrows indicate DNA bands.

By using an incubation time of 3 hours, DNA was obtained from Halimeda macroloba, Amphiroa sp. and Gracilaria sp. which did not work on incubation for 1 hour. DNA that appeared with smear in some seaweed samples indicated that DNA had degraded [12]. DNA breaks into small fragments with small molecular size due to the activity of the nuclease enzymes that cut DNA [13].

Very faint DNA bands were observed for Laurencia sp and Turbinaria sp as shown in Fig. 3 (sample number 7

Figure 4. Electrophoresis of DNA extracted from Turbinaria sp. (1) and Laurencia sp. (2) where 10 µl DNA was loaded for each species. Arrows indicate DNA bands

To test DNA quality, RAPD PCR was carried out using primers UBC 127 and OPD 11. PCR-RAPD technique has widely been used for analyzing the genetic variability in plants. This technique is rapid, simple and does not require prior genetic information of the samples [15]. Result showed that only UBC127 primer produced PCR products and the PCR products were only from 3 samples namely U. reticulata, Amphiroa sp., Sargassum sp (Figure 5). This showed that the quality of DNA was low.

PCR products using UBC 127 primer exhibit thin DNA bands. This may because the conditions in PCR reaction are not yet optimal despite the possibility that there are contaminant compounds contained in seaweed DNA such as carrageenan, alginate, fucoidan and other polysaccharides. These contaminants become inhibitors in the PCR reaction. The presence of polyphenols, and other secondary metabolites also influence PCR reaction [16].

The success of DNA extraction depends on four important steps: effective cell disruption; nucleoprotein complexes denaturation; nucleases inactivation and free from contamination [14].

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1kb

3000 bp

1000 bp

Figure 5. PCR-RAPD of seaweed using primer UBC127. 1. H. opuntia, 2. H. macroloba, 3. Laurencia sp., 4. Turbinaria sp., 5. U. reticulata, 6. Amphiroa sp., 7. Sargassum sp. Arrows indicate PCR products.

PCR with RAPD primers provides a great chance of success for every sample, because RAPD primers are short DNA sequences (10-12 base pairs) making it easier to amplify DNA. Primers with short sequences are highly

likely to be attached to the DNA site of the sample used. According to Bardakci [17] in amplification using RAPD primer, DNA from all sources is capable to amplification.

However, several factors affected the success of RAPD amplification such as DNA quality and PCR-RAPD protocol. Concentrations of primers, MgCl2, template DNA should be optimized [16].

In this study, the colour of extracted DNA was brown indicated contamination with phenolic compounds and the DNA solution was viscous for most samples. The viscosity of DNA shows the co-precipitation of polysaccharide with DNA [18].

DNA extraction from seaweed was reported successful using fresh materials [19]. Furthermore, the treatment with enzymes and grinding with liquid nitrogen have resulted in good quality of DNA [20, 21]. However, enzymes are expensive and liquid nitrogen is not accessible in every area. Commercial DNA extraction kit was also successful in extracting DNA from seaweed [22, 23]. The high price of DNA extraction kit is a limitation in several laboratories. Further modifications of DNA protocol using CTAB lysis buffer need to be studied to obtain high quality and quantity of DNA from seaweed.

-

IV. CONCLUSION

DNA extraction with an incubation time of 3 hours in 2 ml of extraction buffer showed the best results. The quality of seaweed DNA obtained was low as indicated by faint DNA band as well as smeared DNA in several species. The low DNA quality was also indicated by the failure of amplification of seaweed DNA using PCR-RAPD. Only three DNA samples produced PCR product with primer UBC127, while no product for all seaweed DNA tested when primer OPD 11 used.

REFERENCES

-

[1] Jamshidi-Kia F, Z. Lorigooini, H. Amini-Khoei. 2018. Medicinal plants: Past history and future perspective. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol. 7(1): 1-7.

-

[2] Fiedor J, K. Burda. 2014. Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease. Nutrients. 6(2):466–488.

-

[3] Ralley L, E.M.A. Enfissi, N. Misawa, W. Schuch, P.M. Bramley, P.D. Fraser. 2004. Metabolic engineering of ketocarotenoid formation in higher plants. Plant J. 39:477–486.

-

[4] Misawa N, S. Tomy, K. Kondo, A. Yokohama, S. Kajiwara, T. Saito, T. Ohtani, W. Miki. 1995. Structure and functional analysis of a marine bacterial carotenoid biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 177(22): 65756584.

-

[5] Nishida Y, K. Adeshi, H. Kasai, Y. Shizuri, K. Shindo, A. Sawabe, S. Komemushi, M. Wataru, N.

Misawa. 2005. Elucidation of a carotenoid

biosynthesis gene cluster encoding a novel enzyme, 2,2’-β-hydroxylase, from Brevundimonas sp. Strain SD212 and combinational biosynthesis of new and rare xanthophylls. Appl. Environ. Microbiology, 71: 4286-4296

-

[6] Pereira JC, R. Chaves, E. Bastos, A. Leitão, H. Guedes-Pinto. 2011. An efficient method for genomic DNA extraction from different Molluscs species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12: 8086-8095.

-

[7] N’Yeurt, ADR. 1999. A preliminary illustrated field guide to the common marine algae of the Cook Islands. The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji.

-

[8] Al-Yamani FY., I. Polikarpov, A. Al-Ghunaim, T. Mikhaylova. 2014. Field guide of marine macroalgae (Chlorophyta, Rhodophyta, Phaeophyceae) of

Kuwait. Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, Safat, Kuwait.

-

[9] Doyle JJ, J.L. Doyle. 1990. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus, 12: 13-15.

-

[10] Jain SA., F.T. de Jesus, G.M. Marchioro, E.D. de Araújo. 2013. Extraction of DNA from honey and its amplification by PCR for botanical identification. Food Sci. Technol. 33(4): 753-756.

-

[11] Rogers, S.O., A.J. Benedich. 1985. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh herbarium and Mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 5: 69-76

-

[12] Das SS., S. Das (Sur), P. Ghosh. 2013. Optimization of DNA isolation and RAPD-PCR protocol of Acanthus volubilis wall a rare mangrove plant from Indian Sundarban, for conservation concern. European J. Exp. Biol. 3(6):33-38

-

[13] Sahu SK., M. Thangaraj, K. Kathiresan. 2012. DNA extraction protocol for plants with high levels of secondary metabolites and polysaccharides without using liquid nitrogen and phenol. ISRN Mol. Biol. 2012, Article ID 205049, doi:10.5402/2012/205049

-

[14] Tan SC, B. C. Yiap. 2009. DNA, RNA, and protein extraction: the past and the present. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2009, Article ID 574398,

doi:10.1155/2009/574398

-

[15] Shinde VM, K. Dhalwal, K.R. Mahadik, K.S. Joshi, B.K. Patwardhan. 2007. RAPD analysis for determination of components in herbal medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 4(Suppl 1): 21–23. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem109.

-

[16] Skoric M, B. Šiler, T. Banjanac, J.N. Živkov, S. Dmitrovic, D. Misic, D. Grubisic. 2012. The

reproducibility of RAPD profiles: Еffects of PCR components on RAPD analysis of four Centaurium species. Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade, 64 (1), 191-199. DOI:10.2298/ABS1201191S191

-

[17] Bardakci F. 2001. Random amplified polymorphic

DNA (RAPD) markers. Turk. J. Biol. 25: 185-196.

-

[18] Souza HAV, L.A.C. Muller, R.L. Brandão, M.B. Lovato. 2012. Isolation of high quality and polysaccharide-free DNA from leaves of Dimorphandra mollis (Leguminosae), a tree from the Brazilian Cerrado. Genet. Mol. Res. 11 (1): 756-764

-

[19] Ramakrishnan GS, A.A. Fathima, M. Ramya. 2017. A rapid and efficient DNA extraction method suitable for marine macroalgae. Biotech. 7(6):364. doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0992-2.

-

[20] Wang G, Y. Li, P. Xia, D. Duan. 2005. A simple method for DNA extraction from sporophyte in the brown alga Laminaria japonica. J. Appl. Phycol. 17(1):75–79. doi: 10.1007/s10811-005-5557-9.

-

[21] Joubert Y, J. Fleurence. DNA isolation protocol for seaweeds. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2005. 23:197. doi: 10.1007/BF02772712.

-

[22] Irvan R. Hengkengbala, G.S. Gerung, S. Wullur. 2018. DNA extraction and amplification of the rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit) gene of red seaweed Gracilaria sp. from Bahoi Waters, North Minahasa Regency. J.

Aquatic Sci. Management. 6(2): 33-38.

-

[23] Mohammed ZAA., N.A.H. Al–Bdairi, R.K. Abed. 2018. RAPD marker variability among algae species in Iraq. Biochem. Cell. Arch. 18, Suppl. 1: 953-958.

Discussion and feedback