PENAMPILAN ALFALFA (Medicago sativa) DEFOLIASI PERTAMA PADA JARAK TANAM DAN UMUR DEFOLIASI YANG BERBEDA

on

pastura Vol. 6 No. 1 : 25 - 28

ISSN : 2088-818X

PENAMPILAN ALFALFA (Medicago sativa) DEFOLIASI PERTAMA PADA JARAK TANAM DAN UMUR DEFOLIASI YANG BERBEDA

Suwarno, Eko Hendarto, Nur Hidayat, Bahrun, Anisa Dewi Wardani Putri dan Taufik Hidayat

Fakultas Peternakan Universitas Jendral Soedirman, Purwokerto

ABSTRACT

Forage, the main feedstuff for ruminants, includes grasses and legumes, browses, and side products of food crops. However, legumes generally have greater crude protein content relative to other species of forage plants. One of the species of legumes is alfalfa (Medicago sativa), a perennial crop that can grow from the tropics up to sub tropics. In spite of its excellent nutrient content, In Indonesia alfalfa is still not widely explored and used for feedstuff. A study was conducted to explore and evaluate of alfalfa performances in terms of the height, number of tillers, dry matter (DM) and crude protein (CP) productions under the effects of different plant densities and ages of defoliation”. The height of the location of study was 200 m above sea level with an average temperature of 270 C. The results showed that the ranges of the height of alfalfa, the numbers of tillers, DM and CP productions were 33.31-56.32 cm, 36.38-82.36 tillers/bunch, 556.91018.9 kg/ha/defoliation, and 149.75 – 291.79 kg/ha/defoliation, respectively. In general, the ages of plant at the time of defoliation and plant distances affected (P<0.05) the variables being studied. The older plants resulted in greater DM and CP yields, and more densely plantation resulted in greater DM and CP yields.

Keywords: alfalfa, plant density, defoliation age.

INTRODUCTION

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is grown both in temperate and subtropical regions. Although on the global basis Alfalfa has been widely used for forage (Walton, 1983). In Indonesia, the biological characteristics, distribution, exploration, and usage as feedstuff of this forage plant is not yet deeply understood. According to Walton (1983), the center of origin of this forage plant is in Iran, Transcaucasia, and Asia Minor, on where area Alfalfa has evolved to withstand the cold winters and hot, dry summers. The common alfalfa (temperate tolerant) has a blue to purple-colored flowers, relative to M. falcata, a cold-tolerant, that has yellow-colored flowers, has been widely known and has been named “the queen of forages” (Walton,1983), and can be used for grazing, silage, or for hay (Cheeke,1999).

Alfalfa may not grow well in acidic soils, presumably because the specific Rhizobia in alfalfa root nodules are sensitive to pH values below 6.5 Walton, 1983). The root can penetrate the soil up to 3 to 6 m, therefore, alfalfa can relatively survive on dry lands. The part of the taproot just below the crown forms a thick, fleshy storage region for carbohydrate material. The plant grows upright that may reach 1 to 3 m height. There are over 100 alfalfa cultivars in common use, each of which having their areas of adaptation, for instance, Vangard is adapted to live in south eastern US, Rambler, Roamer, Dry lander, Titan are winter hardy, and Granda is disease and insect resistant, however, these cultivars are not flooding

tolerant. Crown root, a bacterial and fungal disease, makes a substantial contribution to winterkill of alfalfa (Walton, 1983). Hanson et al., (1988) said, alfalfa is a perennial plant with a high capacity of production and high forage nutrient content, 49.31 tons of DM/ ha/y, and 26.6 % CP content, respectively. Alfalfa is able to gain fast re growth after defoliation (Dhont et al.,2006). The ideal temperature for the growth of alfalfa is 27O C, however, in Alaska alfalfa can be adapted to less than 25O C. (Frame, 1998). The defoliation of alfalfa can be conducted at the plant age of 28 days in the US (Habben and Folenec (1990), and 21 days in tropical regions (BBPTU or the Center for the Breeding of Excellent Livestock), Baturraden, Central Java.

One of the factors that may affect the growth and production of alfalfa is management, including planting distance and ages of defoliation. On the slope areas, sandy soils, and less fertile lands, it is wise to plant alfalfa in a greater density in order to minimize soil erosion and maximize land use, respectively. However, very high plant density may cause severe competition for alfalfa to obtain soil minerals and sunlight, and greater possibility to contaminate plant disease from one to other plants. Another factor that affects alfalfa production is the age of plant at the time of defoliation. Too old plant at defoliation may product the highest dry matter, however, the nutrient content and feed quality of the forage may suffer (Frame, 1998). On the contrary, too young age at the time of defoliation may cause the least dry matter production and carbohydrate reserves

for the re growth of alfalfa (Undersander et al., 1997). Therefore, some studies are required to evaluate the performance of alfalfa under various plant densities and ages of plant at the time of defoliation.

Some experiments indicated that alfalfa has been studied in terms of its growth and production under the effects of various plant densities and the ages of plant at the time of defoliation, however, the results are not conclusive. The density of alfalfa that was planted in Canada ranged from 11-172 holes of plants/ m2 (Manitoba Agriculture, 1987). In Madison, USA, alfalfas that were planted at a distance of (50 x 50) cm2 or 4 holes/m2, resulted in a fresh yield of 80 kg/ ha/defoliation (Shakra et al., 1969), approximately 16 kg DM/ha/defoliation.

This study was conducted to evaluate the effect of alfalfa density and age of alfalfa at the time of defoliation on the number of tillers and height of alfalfa.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

The materials of this study were alfalfa seeds, 5 seeds/hole, SP-36 fertilizer, 2.16 kg, urea as much as 2.7 kg, and 270 m2 area of land that was divided into 27 paddocks of 10 m2 each. The implements of this study consisted of shovel, skits, meter roll, thermometer, soil tester, and oven.

The used design was nested (Montgomery, 1991), as followed: The first factor as the group consisted of:

J1 : ( 10x 20) cm2 planting distance or 50 holes of plantation/m2, (500,000 holes/ha)

J2 : (15 x 20) cm2 planting distance or 33 holes of plantation/m2, (330,000 holes/ha)

J3 : (20 x 20) cm2 planting distance or 25 holes of plantation/m2, (250,000holes/ha)

The second factor as sub-group, namely

D1 : 21-day old alfalfa at the time of defoliation, (17 defoliations / year)

D2 : 28-day old alfalfa at the time of defoliation, (13 defoliations / year)

D3 : 35-day old alfalfa at the time of defoliation, (10 defoliations / year).

The measured variables were the number of tillers, height of plant, dry matter (DM) and crude protein (CP) productions of alfalfa.

The study was conducted from10th of June until 25th of September 2008, in BPPTU Baturraden. Land for cultivation as width as 400 m2 was divided in to 27 plots of 10m2 each and were fertilized with organic fertilizer (Alvinas), 7 days before seed cultivation as much as 2.5 tons/ha/defoliation. Alfalfa seeds were planted as many as 5 seeds /hole, and fertilized with urea as much as 100 kg /ha / defoliation, 14-day post-planting. There were only 3 plants / hole for all experimental units that were used for analysis and observations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The height of the study location was 758 m above the sea level, the soil was categorized as andosol with the content of 0.75% total N, 88.26% available P, 0.35% total P, and 0.09% total potassium, with an average pH of 6.6 and the moisture range of 6274 % and an average soil moisture of 73.7%. The temperature at the site of study location ranged from 23 C up to 30 C with an average weekly basis of 25.5 C. The yearly water fall (rain intensity) at the site of study was 2000 mm. This kind of soil and climatic condition is still favorable for alfalfa growth and adaptation (Frame, 1998).

The performances of alfalfa under different plant density and the age of plant at defoliation. The means of heights, the number of tillers, an dry matter production of alfalfa under the effect of plant densities and the ages of plant at the time of defoliation was shown in table. Table 1 indicated that the range of height of alfalfa in this study was 38.05 cm to 54.94 cm, the number of tillers was 14.05 up to 24.33/ bunch, DM production was (556.88 – 1018.85) kg/ ha/defoliation, and CP production was 149.75 up to 291.79 kg/ha/defoliation.

In general, the older the alfalfa at the time of defoliation, the greater the height, number of tillers,

Table 1. The means of alfalfa heights, the number of tillers, dry matter and crude protein productions of alfalfa under various plant densities and age of plant at defoliation.

|

Variable |

Age of plant at defoliation(D) |

Plant density | ||||

|

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

J1 |

J2 |

J3 | |

|

Height (cm) |

38.05a |

49.07b |

54.94c |

49.76 |

47.31 |

44.99 |

|

Number of tillers |

14.05a |

20.75b |

24.50c |

17.30 |

19.68 |

22.32 |

|

Dry matter yield (kg/ha/defol.) |

556.88a |

867.69b |

1018.85c |

1011.42a |

773.66b |

658.35c |

|

Crude protein content (% DM) |

26.89 |

27.58 |

26.78 |

28.85 |

26.04 |

26.35 |

|

Crude protein production, kg/ha/defol |

149.75a |

239.31b |

272.85bc |

291.79a |

201.46b |

173.48c |

|

Notes: Ages of plant at defoliation: means at the same row with different super scrip, different (P<0.05). Plant density: means at the same row with different super scrip, different (P <0.05). | ||||||

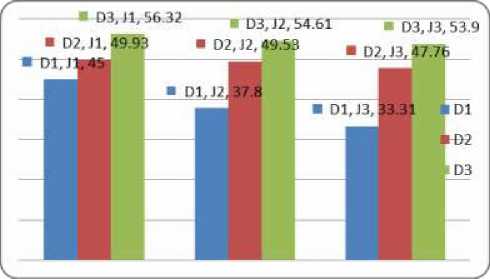

DM and CP yields (P < 0.05). In case of plant density, less densely plants resulted in the tendencies to decrease the height and increase the number of tiller, and decreased significantly (P< 0.5) DM and CP productions. On yearly basis, when alfalfa was defoliated at 21-d old, 28-d, and 35-d, the means of DM productions were assumed to be 9466.96 kg, 11279.97 kg, and 10188.50 kg, respectively, which were still in the range reported by Manitoba Agriculture (1987), that yearly DM yield of alfalfa was approximately 12000 kg. The means of height of alfalfa were shown in figure 1. Similarly, the means of yearly CP productions of various ages of alfalfa at 21-d, 28-d, and 35-d were assumed to be 2595.67, 3111.03, and 2728.50 kg/ha, respectively.

Figure 1. The means of alfalfa height (cm) under the effects of various ages of plant at defoliation (D1, D2, D3) and plant density (J1, J2, J3).

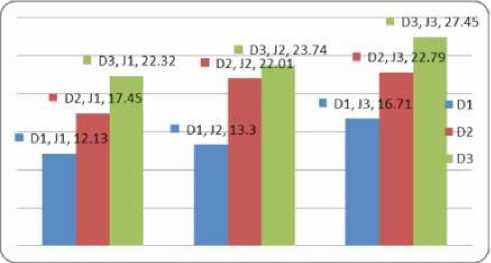

The means of the number of tillers of alfalfa were shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The means of the number of tillers of alfalfa under the effects of various age of plant at defoliation ( D1, D2,D3), and plant density (J1,J2,J3).

The results of DM and CP yields in this study were approximately (75 – 50) % lower relative to those of Caddel et al.,(2006) 4.5 tons of DM/ha/ defoliation, and Hanson et al.,(1988), 4.9 tons of DM/ha/defoliation, presumably because their alfalfa

stands were much older than those in this study and had been defoliated several times, meanwhile alfalfa stands in this study were still young and only experienced first defoliation. The older the plants at the time of defoliation, the greater the DM and CP productions.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the study conclude, alfalfa that was planted in the area with the climate and soil conditions similar to the location in this study, (1) the decrease of plant density from 50 bunches/1 m2. (500,000 bunches/ha) down to 25 bunches/ 1m2 (250,000 bunches/ha) tended to decrease the height of alfalfa and increase the number of tillers, (2) on defoliation basis, the older the alfalfa from 21-d up to 35-d at the time of defoliation, the higher DM and CP productions, (3) more densely populated alfalfa yields greater DM and CP, and (4) on yearly basis, it is assumed that alfalfa achieves the highest DM and CP production when it is defoliated at the age of 28 days, with plant density of 500,000 bunches/ha or at plant spacing of (10 x 20) cm2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to appreciate the BPPTU Baturraden for its generosity to lend the grassland and alfalfa seeds for this study.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Cheeke, P. R., 1999. Applied animal nutrition. Pp. 158-160. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA.

Frame, J., 1998. Medicago sativa L. Food and Agriculture Organization,UNO. PurdueUniversity. http:/ www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/GBASE// data/htm.

Habben, J., and J. Folenec, 1990. Starch grain distribution in taproots of defoliated Medicago sativa.Department of Agronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA. http:// www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi.

Hanson, A.A., D. K. Barnes, and R. R.Hill, Jr. 1988. The importance of alfalfa. The American Society of Agronomy.Monograph number 29.http://www. usda.gov/nass/pubs/agr98/acro98.htm.

Manitoba Agriculture, 1987. Forage’87. Home Study Course, pp.7. Manitoba Agriculture, Manitoba, Canada.

Montgomery,D. C., 1991. Design and analysis of experiments. Pp.439-452. JohnWilley & Sons Inc. New York,USA.

Hidayat, N., Suwarno, and K. Ardani, 2012. The effects of planting distance and defoliation age on production and quality of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Prosiding Seminar Nasional. Teknologi dan agribisnis peternakan dalam menunjang pemenuhan kebutuhan protein hewani nasional. Pp. 121-129. Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Purwokerto.

Shakra, M.A.,M.Akhtar, and D.W. Bray, 1969. Influence of irrigation interval and plant density on alfalfa

seed production. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, USA. http://agron.scijournals.org/cgi/ content/abstract.

Undersander, D., P. Vssalotti, and D. Cosgrove, 1997. Germination and Growth. University of Wisconsin-Extension, Cooperative Extension, St. Madison.

Walton, P. D.,1983. Production & Management of Cutivated Forages. Pp. 79-83. Reston Publishing Company, Inc. Reston, Virginia, USA.

28

Discussion and feedback