Madura Indigenous Communities' Local Knowledge in the Participating Planning and Budgeting Process

on

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis

Vol. 18 No. 1, January 2023

AFFILIATION:

1,3Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Widya Gama, Indonesia

2Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Pancasila, Indonesia

*CORRESPONDENCE:

THIS ARTICLE IS AVAILABLE IN:

DOI:

10.24843/JIAB.2023.v18.i01.p11

CITATION:

Sopanah, A., Harnovinsah, & Sulistyan, R. B. (2022). Madura Indigenous Communities' Local Knowledge in the Participating Planning and Budgeting Process. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 18(1), 163-178.

ARTICLE HISTORY Received:

1 January 2023

Revised:

16 January 2023

Accepted:

27 January 2023

Madura Indigenous Communities' Local Knowledge in the Participating Planning and Budgeting Process

Ana Sopanah1*, Harnovinsah2, Riza Bahtiar Sulistyan3

Abstract

This study aims to reveal how the Madura indigenous communities' local wisdom is in the process of participatory planning and budgeting and determines the model of local community wisdom in the process of participatory planning and budgeting as a whole. This study uses a qualitative ethnomethodological approach with a constructivist paradigm. The study results show that formal deliberations, namely development planning deliberations in general, are almost the same as in other regions in Indonesia. However, in the Madurese indigenous people, there are differences from most other regions in Indonesia, namely that apart from carrying out development planning deliberations, they actually carry out informal deliberations, namely community meetings. Moreover, the implementation of participatory budgeting, which is proven elsewhere, is not proven in the Madurese indigenous people who use community consultations as an initial stage in formulating community needs by providing aspirations in order to achieve local goals.

Keywords: local wisdom, participatory budgeting, planning processes

Introduction

Research on culture and customs in the public sector is currently a major focus worldwide. This is shown by the many calls to conduct research in the field of culture and customs on a massive scale and, more specifically, in the public sector (Broadbent & Guthrie, 2008). Based on this, this is also shown again by the fact that from a cultural perspective regarding participatory budgeting processes at the local government level, there is still relatively little research to do (Sulistyan et al., 2022; Uddin et al., 2017). Many developing and non-developing countries carry out participatory budgeting because it is hoped that indigenous peoples can maintain cultural values to keep them alive (Grillos, 2017) where participatory budgeting is a democratic process in which citizens are involved in making decisions about budgeting (Miller et al., 2017).

Participatory budgeting is interpreted as a form of reform at the local level (Grillos, 2017; Sulistyan et al., 2019). Participatory budgeting itself is very interesting and political because it is software that reduces and simplifies it so that it becomes a set of procedures for

democratizing demand-making (Ganuza & Baiocchi, 2012). Participatory budgeting in this case, makes the allocation of public funds carried out by collecting and combining the preferences of individuals (Benadè et al., 2021). So, participatory budgeting can be said to be a suitable instrument to support and promote citizen or community involvement in government work (Bartocci et al., 2019).

Participatory budgeting has been widely used in local governments in western countries because it is considered a transition towards a pluralistic democracy to be able to make a policy through deliberation and community involvement (Brun-Martos & Lapsley, 2016). However, in accounting research that discusses participatory budgeting in indigenous communities, there is still very little research, especially in Indonesia (Jayasinghe et al., 2020). In this case, local governments in Indonesia are of particular concern because the laws and regulations in force in Indonesia require a participatory budgeting process. The Indonesian government seeks to encourage public participation in local decision-making, namely by establishing a formal mechanism in the form of laws and regulations (Grillos, 2017). The Indonesian government has regulated participatory budgeting through various regulations in laws, government regulations and ministerial regulations. The forms of community participation that have been regulated in laws and regulations in Indonesia are in the form of deliberations on development planning (Jayasinghe et al., 2020; Sopanah, 2010; Sopanah, 2012, 2013, 2015; Sopanah et al., 2017; Sopanah et al., 2013).

The regional budget planning process in Indonesia itself has been regulated in Law Number 25 of 2004 concerning the National Development Planning System, Law Number 23 of 2014 concerning Regional Government, Law Number 33 of 2004 concerning the Financial Balance between the Government and Regional Government, Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 59 the Year 2007 concerning Amendments to Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 13 Year 2006 concerning Guidelines for Regional Financial Management, Government Regulation Number 8 Year 2008 concerning Stages, Procedures for Preparation, Control and Evaluation of the Implementation of Regional Development Plans through Development Planning Meetings. Based on these regulations, it is known that planning and budgeting are inseparable from community participation.

Community involvement in the planning process takes the form of community participation. Participation in the community is also interpreted as a comprehensive view of how society, and communities within society can function (Gieling, 2018). Based on this, community participation is a very important factor in the implementation of autonomy, accountability, and democratic emancipation at the local level. Apart from that, the issue of participation for indigenous communities has been introduced previously. For example, the form of indigenous community participation is reflected in the fact that for centuries indigenous peoples have survived in a unique way and carried out moral accountability through community involvement and participation. However, the implementation of participatory budgeting can also lead to various unexpected consequences from the point of view of applicable national regulations, namely, among other things, indigenous peoples act to preserve traditional cultural practices, and at the same time, indigenous peoples also take into account funding through the regional budgeting process (Jayasinghe et al., 2020).

In addition, there are also problems in the implementation of participatory budgeting, which are found in many European countries and the United States, especially as research conducted by Allegretti & Falanga (2016) which states that the majority of

gender issues are marginalized in the implementation of participatory budgeting, which has an impact negative on the level of public participation in participatory budgeting and implementation at the local level. Furthermore, in the context of developing countries, there is criticism regarding the stages of participatory budgeting, which are seen as weakening trust or social capital between politicians and the public. An example is participatory budgeting in local governments in the country of Sri Lanka, which illustrates how the participatory budgeting process is politicized and used by politicians to extend political tenure or to secure higher office positions (Kuruppu et al., 2016).

As a result, the erosion of public confidence has had a negative effect on participatory budgeting implementation as well as on people's engagement in formal politics. Because of this, there is also a chance that public trust and engagement in the regional budgeting process will decline (Falanga & Lüchmann, 2019). The implementation of participatory budgeting in some local governments has only been a consultative process and only a formality (Uddin et al., 2017), while in other local governments, it has not only been limited to consultations but has also succeeded in creating innovative proposals in the regional budgeting process. For example, the reality of local government in Estonia, where participatory budgeting processes are directly influenced by the desire to follow emerging trends (Krenjova & Raudla, 2017).

In previous research on the tengger indigenous people (Jayasinghe et al., 2020; Sopanah, 2013, 2015; Sopanah et al., 2013) and on the osing indigenous people (Sopanah et al., 2017) shows that these two indigenous peoples have differences from other regions, namely that apart from carrying out formal mechanisms such as holding development planning meetings, they also carry out informal mechanisms such as village meetings. In addition, the two indigenous peoples are also categorized as fully participating. The participatory budgeting in the two indigenous peoples is also inseparable from the local area's cultural values or wisdom.

In the research conducted so far, no one has discussed the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people in forming a participatory planning and budgeting process model. Based on this, in this study, the researcher was interested in knowing the planning and budgeting process in the Madurese indigenous people by incorporating local wisdom values. The formulation of the research problem is how is the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people in the process of participatory planning and budgeting. The purpose of this research is to reveal how the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people is in the process of participatory planning and budgeting and to determine the model of the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people in the process of participatory planning and budgeting as a whole. Therefore, with this research focusing on the Madurese indigenous people, it is possible to find meanings different from other regions through the value of local wisdom in participatory planning and budgeting processes among the Madurese indigenous people.

Research Method

This study uses a qualitative research approach with a constructivist paradigm, and the research design is ethnomethodology. Qualitative research is an approach used to explore and also to understand the meaning, both from individuals and groups, in observing a social problem (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Then in the constructivism paradigm, researchers learn to understand the various realities that have been constructed by individuals and the implications of these constructions in their lives (Patton, 2014).

Table 1. Research Informants

|

Informant (Initials) |

Position | |

|

1 |

Informant JH |

Pamekasan District Inspectorate |

|

2 |

Informant FR |

Village Assistant from Kementerian Desa PDTT |

|

Republik Indonesia | ||

|

3 |

Informant MT |

Head of Government Affairs |

|

4 |

Informant HD |

Head of Affairs of the Public Service Section |

|

5 |

Informant IP |

Headman |

|

6 |

Informant RF |

Member of Badan Permusyawaratan Desa |

|

7 |

Informant MY |

Madurese Indigenous Community Figures |

|

8 |

Informant BM |

Madurese Indigenous Community Figures |

|

9 |

Informant WF |

Member of Karang Taruna |

|

10 |

Informant MD |

Community |

Source: Processed Data, 2022

Furthermore, the ethnomethodological research design is a study that is used to examine how individuals create and understand their daily lives, such as the way they complete work in everyday life (Yin, 2018).

This study uses two minor propositions, including the first minor proposition, namely the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people, and the second minor proposition, namely the participatory planning and budgeting process of the Madurese indigenous people, which then results from the two minor propositions as a major proposition. The location of this research is in the Madurese indigenous people who are located on Madura Island, more precisely in Pamekasan Regency, East Java Province, Indonesia. Then in determining informants, researchers used four criteria to be able to determine informants (Neuman, 2014), which include people involved in the field and experienced, people involved in the field, people who spend time with researchers, and people who are non-analysts or Use pragmatic common sense. As for this study, there were ten informants, in which the informant identity only used initials to replace the actual informant's name. The informants of this study are shown in Table 1.

Then the research data was obtained through interviews, observation and documentation to explore and understand the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people in the participatory planning and budgeting process. The procedure for analyzing data in this study includes data collection, data reduction, data presentation, and drawing conclusions. The selection of data analysis procedures is based on researchers' desire to identify, analyze, describe, and interpret research findings (Yin, 2018).

Result and Discussion

Local wisdom and cultural values of the Madurese indigenous people are still there and continue to be preserved by the community, even though a lot of modernization has entered their environment. The entry of modernization does not make the cultural identity that remains preserved and firmly held by the Madurese indigenous people fade. This cultural identity is reflected in various traditional activities that the Madurese indigenous people routinely carry out.

The culture attached to the Madurese indigenous people is seen as a belief in ancestral cultural heritage that is guaranteed to be authentic and preserved until now. In this case, the researcher has made observations for about three months and attended

various traditional activities that are routinely carried out by the Madurese indigenous people, which include Karapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok, and Rokat Tase'. Based on these customary activities, researchers can conclude that many local wisdom values exist in the Madurese indigenous people, explicitly and implicitly, through informants' statements in this study. For example, the researcher interviewed with the informant MY as, a leader of the Madurese indigenous people, who stated that related to traditional Madurese activities and the local wisdom values of the Madurese indigenous people:

"The Madurese people carry out traditional activities, namely karapan sapi or a type of cow racing competition, which aims to unite the Madurese people from Sumenep to Bangkalan"

"Then there is the sonok cow, which is a pair of male and female cows conducting a beauty contest accompanied by saronen and gamelan, the purpose of which is to strengthen community relations throughout Madura"

"Then there is also pick the sea or in the Madurese language it is rokat tase' which begins with istigosah for one day and one night, after that a boat is lost which contains all the fruits on the market, excavated fruits such as cassava, taro and sweet potatoes, then a bunch of bananas, coconut, siwalan, sugarcane and a live chicken with white fur and blue legs. If you don't get the chicken, said the Madurese it is bliring koning or a slightly yellowish chicken. Then put everything into a plywood boat, and they were escorted to the edge of the reef. This rokat tase's purpose is a form of people's gratitude to God.

"Usually, the community gathers apart from village meetings which are facilitated by the village; there are community meetings or community meetings initiated by the community itself as a place for friendship between residents which is usually marked by a tumpengan and a place for communication between communities" "The values of the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people that are still being maintained are mutual cooperation, mutual help, harmony, tolerance, honesty and self-esteem which is commonly called Carok whose term in Madurese is atembang pote'mata, ango'an pote tolang which means compared to me being ashamed or losing dignity, I would rather die”

Furthermore, the researcher again conducted interviews with the BM informant who was also a Madurese traditional community leader, in which the BM informant stated that related to traditional Madurese activities, namely Rokat Tase', Karapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok and local wisdom values in the Madurese indigenous community as follows:

"In Madura there are preserved traditional activities such as rokat tase' or salametan (thanksgiving), where this rokat tase' is a thanksgiving carried out by the Madurese community as a sign of gratitude by offering agricultural, livestock and marine products. For example, if a farm is like a yellowish chicken and also a cow's head, which is then released into the sea."

"Kerapan sapi is a locality because it is typical of Madura; from ancient times, it was a tradition of bull races, so after obtaining agricultural products, people need entertainment and are involved in bull races because cows are also part of the commodities of the Madurese people. So as a form of gratitude for agricultural products and so on, especially as a gathering event which is marked by a party, which is called Karapan Sapi"

"There is also a beautiful cow contest, the Madurese term for sonok cow. But indeed it takes longer to hold cows than sonok cows."

"Then in Madura there is a local wisdom that develops in the community, the term in the Madurese language is bada pakon bada feed which means there is an order or instruction yes there is money"

"When it comes to improving welfare, the term in Madurese local wisdom is in the Madurese language, montro adhering adhege, which means if you want to prosper or increase the economy, yes, trade or entrepreneurship."

"Then the local wisdom in Madura to maintain self-esteem, the Madurese term is better pote tolang than pote mata, meaning that it is better to die than self-esteem being trampled on and there is also local wisdom in Madura that is more about togetherness"

"In Madura, the village head is more dominant at the village level, so all matters are that the village head must understand, so being a village head is a big responsibility. The village head in Madura is certainly not the same as the village head in other areas because the village head or village leader, such as when there is a death, birth or marriage, must be visited (visited) by the entire community, where the figure of the village head must protect, know, and understand the meaning of community existence. So even though the village head is carrying out development, he must also protect the whole community without exception, because the position of village head is a dignity or self-respect, existence, and becomes a pride or as a prestige and so on".

Furthermore, the researcher conducted interviews with IP informants as the Village Head, who stated that they were related to traditional Madurese activities, namely rokat tase' as follows:

"rokat tase" or in Indonesian, it is called pick the sea; that is, the aim is to maintain the safety of the village in which there is also istigosah, then for the prosperity of the village. In essence, asking God is not shirk; that is the intention because these traditional activities have also been passed down from our ancestors."

Based on the results of observations and the results of interviews conducted with MY informants, BM informants, and IP informants above, it is explicitly revealed that the Madurese indigenous people have local wisdom values that have been maintained and preserved to this day, which include mutual cooperation, helping each other, harmony, tolerance, togetherness, honesty, atembang pote'mata, ango'an pote tolang (self-respect or dignity), bede pakon bede feed (superior instructions), montro adheging adhege (welfare), and nguripi (protecting).

In addition, the purpose of the traditional activities of karapan sapi, sapi sonok, and rokat tase' is to unite, and strengthen community relations in Madura and is a gathering place for the Madurese community, as well as a form of community gratitude for agricultural, livestock and marine products, which which is marked by the Karapan Sapi and Sonok Cow parties. Then the traditional rokat tase' activity also has a goal, namely to maintain the safety and prosperity of the village, as well as a form of community gratitude to God for the results from agriculture, livestock and marine products which are carried out by carrying out istigosah one day and night and followed by carrying out a lost boat, namely putting in the results agriculture, animal husbandry, and marine products into boats, then released into the sea. Furthermore, there is also a deliberation or discussion of residents, one of the goals of which is as a place for friendship between residents and a forum for communication between communities. Therefore, the researcher then obtained the meaning of the part of the theme of the local wisdom of the Madurese

Table 2. Minor Proposition I: Local Wisdom of the Madurese Indigenous People

|

Informant |

Meaning |

Themes |

|

Informan MY |

Traditional activities that Madurese traditional local | |

|

Informan BM |

the Madurese indigenous wisdom values: people routinely carry 1. Mutual Cooperation | |

|

Informan IP |

out:

Laut)

|

(Petik 5. Integrity

ango’an pote tolang

|

Source: Processed Data, 2022

indigenous people, as shown in Table 2.

Based on Table 2, it can be concluded that the traditional activities of karapan sapi, sapi sonok, rokat tase' and resident rembug are formed by local wisdom values which are maintained and preserved to this day, including mutual cooperation, mutual help, harmony, tolerance, honesty, atembang pote'mata, ango'an pote tolang (self-respect or dignity), bede pakon bede feed (superior instructions), montro adheging adhege (welfare), and nguripi (protecting).

After conducting an analysis in formulating the first minor proposition, namely regarding local indigenous Madurese wisdom, the researchers returned to conducting research on the second minor proposition, namely regarding participatory planning and budgeting processes in the Madurese indigenous community. Where the planning and budgeting process in Indonesia is carried out through development planning meetings, which are annual forums for making agreements on development work plans for the planned fiscal year. The implementation of development planning deliberations starts from the lower level to the upper level.

In this case, the researcher made observations by attending and participating in the planning and budgeting process and observing all stages of planning and budgeting, both formally, such as development planning meetings and informally, such as community consultations. This community gathering activity is a form of informal deliberation in which each village carries out the preparation and implementation stages. However, there are no provisions regarding informal deliberations such as community consultations, either in the form of policies or laws and regulations.

This community meeting provides broad freedom to the whole community, so every citizen has the same right to attend and express their aspirations. Then, after all the aspirations of the community at the hamlet level have been collected, these aspirations will become material for proposals in development planning meetings. Based on this, the researcher then conducted interviews with the IP informant as the Village Head in order to find out the participatory planning and budgeting process as follows:

"The mechanism for preparing the budget is carried out through village meetings, where previously community aspirations were accommodated first at the hamlet level through regular consultations, then later kelebun (village heads), representatives from village consultative bodies, village assistants, community

leaders, religious leaders, representatives of youth organizations, PKK representatives (women), community representatives represented by the head of the sub-village, as well as among desa (village officials) hold deliberations to determine what activities have the most urgency and priority to be funded through deliberations on development planning"

"Community participation here is very good, this can be proven by the many aspirations and suggestions from the community, but we also admit that our funds are limited, so we only choose proposals that are according to our needs." "Usually, in one year, the budget is not certain; it depends on transfers from the central government, namely village funds and if the allocation of funds is from the regional government. Furthermore, village funds from the central government are currently being cut for handling COVID-19 by a few per cent (budget refocusing), then there is also a special budget for disasters, so that percentage, then the budget for infrastructure is also divided again, such as for making gutters, then in the field of empowerment. Finally, there is a posyandu; for more details, you can see the front page of this village office, and there are billboards about the complete village income and expenditure budget for the 2021 fiscal year.

"During the implementation of development, the community is also involved, and the people who work are paid, so here it uses cash-intensive work in the implementation of development."

"The accountability process here has an SPJ (accountability report) in the form of a complete document, and the budgeting process goes through the system. The current term is the operator through the village financial system from the subdistrict."

Furthermore, the researcher again conducted interviews with the informant JH as the Pamekasan District Inspectorate regarding the participatory planning and budgeting process whose implementation was in Madura, as follows:

"To carry out development planning meetings, invite the community (representatives), community leaders, village consultative bodies are also invited, among (village officials) and other community elements, then deliberate at the village hall to determine the budget from the government which in this case is for anything that needs to be implemented first (priority)."

"community involvement through the hamlet head, and the community can make suggestions to the hamlet head, because the hamlet head is present at the development planning meeting and must be present at all, so that the planning carried out in Madura, especially in the village goes according to applicable regulations, such as involving Public."

"After the deliberations and the process is complete, the priority proposals are immediately brought to the sub-district. If the majority agree to be funded, they will be signed by the sub-district head and then returned to the village. So in Madura, everything has to be like that."

"Those who carry out the development are definitely the authority of the village if it costs more than one hundred million using a consultant, but if it is less than one hundred million, it will be handled by the village itself by involving the community and paid for through a program called cash labour intensive."

"The accountability process here is still carried out, usually in the form of documents like that. However, for example, if there is a discrepancy between the

nominal budgeting, the nominal implementation of development and the nominal that is held accountable, then it can be reported to non-governmental organizations and ultimately also the inspectorate, which is involved in investigating and handling this matter, so here the point is honesty.

Next, the researcher also conducted interviews with FR informants as village assistants from the Ministry of Village, PDTT, Republic of Indonesia, as follows:

"I am a village assistant, so I am also involved; then there are community representatives (hamlet heads), community leaders, religious leaders, youth organizations, PKK (women's representatives), especially village officials and village consultative councils, whose purpose is to hold development planning meetings in the following year. Future or so-called development work plan. So that there is a process of involving the community, and usually around thirty-five people are present."

"So future village planning is usually carried out in the current year in the range of July to September through community consultations, then village development planning meetings from the regional revenue agency range from January to February covering proposals from each village."

"So that I, as the village assistant, also play a full role in the planning process by inviting community participation through community consultations at the hamlet level, development planning meetings, then overseeing the development implementation process in the village, to checking the size of the development plan against the size of the physical development. The village assistant monitors this up to accountability matters, so we only supervise, monitor, and facilitate that; moreover, I am a village assistant in the sub-district overseeing 27 villages."

"After planning, there will definitely be development implementation, and for the current regulation, it is necessary to involve the community; in the village now, there is a term labour-intensive village cash in development, such as making new ditches and other infrastructure that is done by the community."

"Accountability is administrative only in the form of documents, but there is also a village head accountability meeting which is usually held at the end of the year."

In addition, researchers also conducted interviews with MT informants as heads of government affairs, as follows:

"For the planning and budgeting process, the residents usually give suggestions, and then they are accommodated in each hamlet, where each hamlet must make a proposal to the village. Then the development planning meeting is usually attended by the community, of course, because of the form of community involvement, then also community leaders, youth organizations, PKK (women's representatives), religious leaders and so on, maybe around forty people are present. Then for proposals in the village, it is more or less usually what is funded by nine hundred million rupiahs."

"then, in the implementation of development, it is definitely like infrastructure, and the community is also involved so that the labour comes from the community but is also paid."

"accountability is usually a document, and the form of transparency is through a banner that we have put up in front of the village office."

Then the researcher also conducted another interview with the HD informant as the head of public service affairs, as follows:

"First, the community proposes to the hamlet head first through community consultation in the hamlet; then later, the hamlet head goes to the village hall to participate in development planning meetings with materials proposed from the previous hamlet level."

"Implementation of the development comes from the village, but for those who work in the development, the community is involved."

"accountability is only documented because at this time there is still a pandemic like that"

The researcher also conducted interviews with RF informants as members of the village consultative council, as follows:

"During the planning and budgeting process, proposals from each hamlet are usually discussed at the village hall, and the organizers of these meetings are from the village consultative body.

"For the implementation of development, the community is involved, so it is not only up to the planning process but also implementation; usually the community is involved in the development and also gets income from it."

"Then for the accountability process, there must be a village head accountability meeting witnessed by the community as well."

Furthermore, the researchers conducted interviews with MY informants and BM informants as Madurese traditional community leaders at the MY informant's house, where MY informants and BM informants stated that:

"Yes, regarding the planning and budgeting process, the community is involved in the form of providing aspirations which are conveyed at informal village meetings, the term here is community consultation at the hamlet level, and after that, the aspirations or suggestions of the community are used as material in development planning meetings. So, community participation is also certain. Yes, but indeed the system is representative of."

"Implementation of development, the community is involved again; usually the energy comes from the community and operational materials for development from the village."

"Accountability is also the same; the community is involved and is present at the accountability meeting because the village government is carrying out the development, so the village head is responsible in front of the community. Administratively, it is in the form of an accountability report."

Next, the researcher also conducted an interview with informant WF a member of the youth group, in which the informant WF stated that:

"For development planning meetings, youth organizations are also involved as well as other community components."

"The people here always participate in the development or clean the village like that because apart from being involved, the community also gets paid."

"As for accountability here, what I know is only in the form of documents"

Then finally, the researcher conducted interviews with the MD informant as the Madurese indigenous people as follows:

"I once submitted a budget for community development to the hamlet head like a training program because the people here want to progress through coaching from a training program."

"The community is invited to carry out development, and usually the village assistant encourages the community to be active."

"Responsibility is like making a report on activities that have been carried out."

After conducting interviews with the ten informants above, the researchers obtained supporting data in the form of an Income and Expenditure Budget for one of the villages in Madura, namely Branta Tinggi Village for the 2021 fiscal year, which includes village development, community development, community empowerment and urgent handling. The number of proposals for development planning meetings in Branta Tinggi Village for village development is Rp655,468,000, community development Rp50,021,627, community empowerment of Rp35,282,920, and urgent handling of Rp144,000,000. So that the total proposal funded in the 2021 fiscal year is Rp884,772,547.

In interviews conducted with IP informants, JH informants, FR informants, MT informants, HD informants, RF informants, MY informants, BM informants, WF informants and MD informants, as well as the income and expenditure budget data for the village of Branta Tinggi, it is explicitly revealed that There are two types of deliberations in participatory planning and budgeting processes, namely informal deliberations such as community consultations and formal deliberations such as development planning deliberations. However, these two types of deliberations are also reflected in community participation, resulting in meaningful planning and budgeting processes, development implementation and accountability processes.

Based on the results of observations, supporting data, and interview results, the meaning of part of the themes of participatory planning and budgeting processes in the Madurese indigenous people is obtained, as shown in Table 3.

Based on Table 3, it can be concluded that planning and budgeting processes, development implementation and accountability processes are dimensions of informal deliberations, such as community discussions and formal deliberations, such as development planning deliberations. Next, the researcher arranges the major propositions obtained from the first set of minor propositions and the second minor propositions, which are shown in Table 4.

The Madurese indigenous people have local wisdom values that are maintained and preserved to this day, which include mutual cooperation, mutual help, harmony, tolerance, honesty, atembang pote'mata, ango'an pote tolang (self-respect or dignity), bede pakon bede feed (superior instruction), montro adheging adhege (welfare), and

Table 3. Minor Proposition II: Participatory Planning and Budgeting Process in the Madurese Indigenous People

|

Informant |

Meaning |

Themes |

|

Informant IP |

Planning and budgeting |

Types of Deliberation in |

|

Informant JH |

processes, Development |

Madurese Customs: |

|

Informant FR |

Implementation, and |

1. Formal Meeting |

|

Informant MT Informant HD |

Accountability Processes |

(Development Planning Conference) |

|

Informant RF Informant MY Informant BM Informant WF Informant MD |

2. Informal Meeting (Rembug Warga) |

Source: Processed Data, 2022

Table 4. Major Proposition: Traditional Madurese Local Wisdom in Participatory Planning and Budgeting Processes

Minor Propositions The conclusions obtained

I The traditional activities of karapan sapi, sapi sonok, and rokat

tase' are shaped by local wisdom values that are maintained and preserved to this day, including mutual cooperation, mutual help, harmony, tolerance, honesty, atembang pote’ mata, ango’an pote tolang (self-respect or dignity), bede pakon bede pakan (superior instructions), montro adheging adhege (welfare), and nguripi (protecting).

II Planning and budgeting processes, development

implementation and accountability processes are dimensions of informal deliberations such as community consultations and formal deliberations such as development planning deliberations.

Source: Processed Data, 2022

nguripi (protecting), which from these local wisdom values gave birth to a custom or cultural activity such as karapan sapi, sapi sonok, and rokat tase' so that it can be said the participation of the Madurese indigenous people is very good. Based on this, the community is also involved in planning and budgeting processes and implementation of development and accountability processes, which in this case reflects the existence of informal deliberations, namely community meetings and formal deliberations, namely development planning deliberations. Therefore, with development meetings and community consultations, the planning and budgeting process, the implementation of development and the accountability process can run properly and even be carried out.

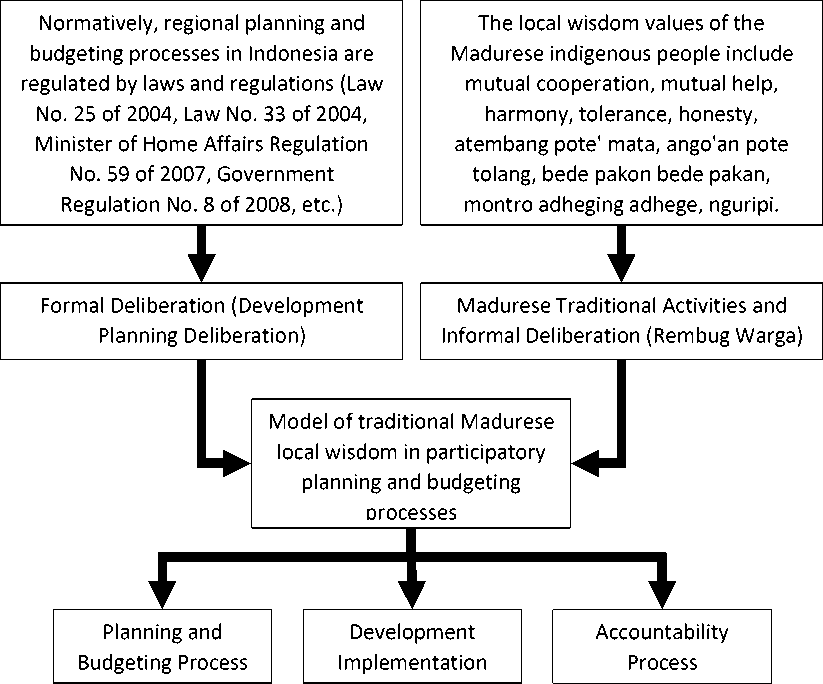

After preparing the major propositions above, the researchers then formed a model of traditional Madurese local wisdom in the participatory planning and budgeting process, which is depicted in Figure 1.

It is known that the implementation of formal deliberations and informal deliberations on the Madurese indigenous people in this study is in line with research conducted on the Tengger indigenous (Jayasinghe et al., 2020; Sopanah, 2013, 2015; Sopanah et al., 2013) and on the osing adat (Sopanah et al., 2017), which in this study resulted in findings indicating that formal deliberations, namely development planning deliberations among the Madurese indigenous people, are generally implemented in almost the same way as other regions in Indonesia. However, the Madurese indigenous people are different from most other regions in Indonesia, namely that apart from holding formal meetings, such as development planning meetings, they also carry out informal meetings, such as community meetings.

Furthermore, the implementation of participatory budgeting in developing countries is considered to have very little evidence of meaningful and fair participation in the participatory budgeting process. The reason is that there is political dominance and the personal interests of public officials in the participatory budgeting process so that public trust is increasingly eroding from various levels of society (Aleksandrov et al., 2018; Aleksandrov & Timoshenko, 2018; Célérier & Botey, 2015; Kuruppu et al., 2016). But on the contrary, the findings of this study indicate that the implementation of participatory budgeting, which is proven elsewhere, is not proven in the Madurese indigenous people.

Figure 1. Model of Traditional Madura Local Wisdom in Participatory Planning and Budgeting Processes

Source: Data Processed (2022)

In this case, the Madurese indigenous people consider that informal deliberations, namely community meetings, are one of the core activities of the original culture that has been passed down from generations of Madurese traditional ancestors and has been maintained to this day. Based on this, the Madurese indigenous people use informal meetings as an initial stage in formulating community needs by providing aspirations or proposals, which representatives of the community then convey to the village head in formal meetings, namely development planning meetings, in order to achieve their local goals. Apart from that, the Madurese indigenous people are guided by the values of local wisdom, namely togetherness (silaturahmi) which is reflected in the implementation of informal meetings, namely community meetings. However, the Madurese indigenous people continue to carry out their obligations to the government by being involved in the planning and budgeting processes regulated in the statutory regulations.

In addition, this study's findings align with the theory of Sopanah et al. (2017), which explains that the values embedded in the local wisdom of indigenous peoples in East Java Province are based on the concept of life built from the regional locality. The life in question consists of three sets of dominant relationships: humans and gods, humans and humans, and humans and their natural environment. The relationship between humans and God is manifested by religious actions such as praying or meditating

according to their respective religious beliefs and participating in various traditional activities. In the Madurese indigenous people, the relationship between humans and God has been carried out, such as carrying out istigosah and various traditional activities, including karapan sapi and cow sonok rokat tase', and community gatherings.

Furthermore, the relationship between humans and humans has also been shown by helping each other and cooperation between communities. In the Madurese indigenous community, the relationship between humans and humans has been carried out, which is reflected in various traditional activities, namely karapan sapi, sapi sonok, rokat tase', and community gatherings. As for carrying out these traditional activities, it also requires the role of the community to participate in the success of all these traditional activities. Next is the relationship between humans and the natural environment, manifested by carrying out customary activities related to natural cycles and protecting the natural environment. In the Madurese traditional community, this has also been carried out, namely, one such as rokat tase', where the intent and purpose of carrying out this rokat tase' traditional activity is in addition to expressing gratitude to God, but also to maintain regional safety.

Conclusion

This research confirms the local wisdom of the Madurese indigenous people in the participatory planning and budgeting process, which proves that apart from being involved in formal development planning meetings as a form of carrying out their obligations to the government, they also carry out informal meetings, one of which is community consultation. This community gathering activity is a core activity of Madurese culture guided by local wisdom values, in which the entire community can attend and convey their aspirations which community representatives then accommodate so that all aspirations that have been accommodated become material for formal deliberation proposals, namely during the implementation of development planning deliberations. Therefore, deliberations on development planning and community consultation activities are considered an inseparable series so that formal and informal deliberations are not just a mere formality but are real mechanisms in their implementation.

The empirical implications of the findings of this study will benefit local governments in Indonesia, especially Bangkalan, Sampang, Pamekasan and Sumenep districts, to increase public participation in budget preparation. Meanwhile, for the community in general, this research can provide opportunities and easy access to participate in conveying aspirations, programs and activities that are more effective and efficient without discrimination.

Furthermore, the theoretical implication of the findings of this research is to provide a theory about community participation in the regional budgeting process that the wider community can apply. This research can also contribute to strengthening concepts related to budgeting based on local wisdom values based on the characteristics of each region and also contribute to creating new model findings related to local wisdombased planning and budgeting processes, which it is hoped that the results of this research can contribute in the development of public sector accounting knowledge in the area of regional budgeting.

Research related to participatory planning and budgeting processes based on local wisdom is still minimally researched, so the researchers provide recommendations to future researchers to be able to conduct research related to local wisdom-based

regional budgeting while still being adjusted to the characteristics of each region in order to be able to contribute to the development of knowledge public sector accounting in the field of public budgeting based on the value of the locality of an area.

References

Aleksandrov, E., Bourmistrov, A., & Grossi, G. (2018). Participatory budgeting as a form of dialogic accounting in Russia. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(4), 1098-1123. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-02-2016-2435

Aleksandrov, E., & Timoshenko, K. (2018). Translating participatory budgeting in Russia: the roles of inscriptions and inscriptors. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 8(3), 302-326. https://doi.org/10.1108/jaee-10-2016-0082

Allegretti, G., & Falanga, R. (2016). Women in Budgeting: A Critical Assessment of Participatory Budgeting Experiences. In Gender Responsive and Participatory Budgeting (pp. 33-53). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24496-9_3

Bartocci, L., Grossi, G., & Mauro, S. G. (2019). Towards a hybrid logic of participatory budgeting. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 32(1), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpsm-06-2017-0169

Benadè, G., Nath, S., Procaccia, A. D., & Shah, N. (2021). Preference Elicitation for Participatory Budgeting. Management Science, 67(5), 2813-2827. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3666

Broadbent, J., & Guthrie, J. (2008). Public sector to public services: 20 years of “contextual” accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(2), 129-169. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570810854383

Brun-Martos, M. I., & Lapsley, I. (2016). Democracy, governmentality and transparency: participatory budgeting in action. Public Management Review, 19(7), 1006-1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1243814

Célérier, L., & Botey, L. E. C. (2015). Accounting, accountants and accountability regimes in pluralistic societies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28(5), 739772. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1245

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Falanga, R., & Lüchmann, L. H. H. (2019). Participatory budgets in Brazil and Portugal: comparing patterns of dissemination. Policy Studies, 41(6), 603-622. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1577373

Ganuza, E., & Baiocchi, G. (2012). The Power of Ambiguity: How Participatory Budgeting Travels the Globe. Journal of Public Deliberation, 8(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.142

Gieling, J. (2018). A place for life or a place to live: Rethinking village attachment, volunteering and livability in Dutch rural areas University of Groningen].

Grillos, T. (2017). Participatory Budgeting and the Poor: Tracing Bias in a Multi-Staged Process in Solo, Indonesia. World Development, 96, 343-358.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.019

Jayasinghe, K., Adhikari, P., Carmel, S., & Sopanah, A. (2020). Multiple rationalities of participatory budgeting in indigenous communities: evidence from Indonesia. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(8), 2139-2166. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-05-2018-3486

Krenjova, J., & Raudla, R. (2017). Policy Diffusion at the Local Level: Participatory

Budgeting in Estonia. Urban Affairs Review, 54(2), 419-447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416688961

Kuruppu, C., Adhikari, P., Gunarathna, V., Ambalangodage, D., Perera, P., & Karunarathna, C. (2016). Participatory budgeting in a Sri Lankan urban council: A practice of power and domination. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 41, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2016.01.002

Miller, S. A., Hildreth, R. W., & Stewart, L. M. (2017). The Modes of Participation: A Revised Frame for Identifying and Analyzing Participatory Budgeting Practices. Administration & Society, 51(8), 1254-1281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399717718325

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Method (4th ed.). Sage Publication.

Sopanah. (2010). Studi Fenomenologis: Menguak Partisipasi Masyarakat Dalam Proses Penyusunan APBD. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Auditing Indonesia, 14(1), 1-21.

Sopanah, A. (2012). Ceremonial Budgeting: Public Participation in Development Planning at an Indonesian Local Government Authority. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 10(2), 73-84.

Sopanah, A. (2013). Partisipasi Masyarakat Dalam Proses Penganggaran Daerah Berbasis Kearifan Lokal (Studi Pada Masyarakat Suku Tengger Bromo Jawa Timur) [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] Universitas Brawijaya]. Malang.

Sopanah, A. (2015). Dibalik Ceremonial Budgeting: "Rembug Desa Tengger" Partisipasi Nyata Dalam Pembangunan. Simposium Nasional Akuntansi XVIII,, 1-26.

Sopanah, A., Meldona, M., Safriliana, R., & Harmadji, D. E. (2017). Public participation on local budgeting base on local wisdom. International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 3(11), 10-18.

Sopanah, A., Sudarma, M., Ludigdo, U., & Djamhuri, A. (2013). Beyond ceremony: The impact of local wisdom on public participation in local government budgeting. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 11(1), 65-78.

Sulistyan, R. B., Cahyaningati, R., Carito, D. W., Taufik, M., & Samsuranto. (2022).

Pelatihan Batik Papring: Upaya Peningkatan Ekonomi Masyarakat Lingkungan Papring Banyuwangi. The 5th Conference on Innovation and Application ofScience and Technology (CIASTECH2022),

Sulistyan, R. B., Setyobakti, M. H., & Darmawan, K. (2019). Strategi Pemberdayaan Masyarakat melalui Program Pembentukan Destinasi Wisata dan Usaha Kecil. Empowerment Society, 2(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.30741/eps.v2i2.457

Uddin, S., Mori, Y., & Adhikari, P. (2017). Participatory Budgeting and Local Government in a Vertical Society: A Japanese Story. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(3), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852317721335

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6 ed.). SAGE Publishing.

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 2023 | 178

Discussion and feedback