Analyzing and Formulating a Statutory General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) in Indonesia

on

Wijaya and Kusumaningtyas, Analyzing and Formulating... 35

Analyzing and Formulating a Statutory General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) in Indonesia

Suparna Wijaya1

Dewi Sekarsari Kusumaningtyas2

1,2Department of Tax, Polytechnic of State Finance STAN, Indonesia

email: suparnawijaya88@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24843/JIAB.2020.v15.i01.p04

Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis

(JIAB)

Volume 15

Issue 1

January 2020

Page 35 - 48

p-ISSN 2302-514X

e-ISSN 2303-1018

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

Received:

28 June 2019

Revised:

18 September 2019

Accepted:

28 November 2019

ABSTRACT

Dealing with the practice of tax avoidance in general, many countries have compiled and implemented their own general anti-avoidance rules (GAAR). This research aims to explore the potential of statutory GAAR in handling tax avoidance practices in Indonesia and SAAR formulas that are suitable for the Indonesian context. This qualitative research employed a case study approach. Results show that the application of SAAR and the principle of substance over form in Indonesia cannot yet be applied properly; thus GAAR is needed. It is expected that the implementation of statutory GAAR can accommodate the limitations of regulators in light of unknown and future tax avoidance schemes.

Keywords: Tax-avoidance, tax planning, specific anti avoidance rule (SAAR), international tax.

INTRODUCTION

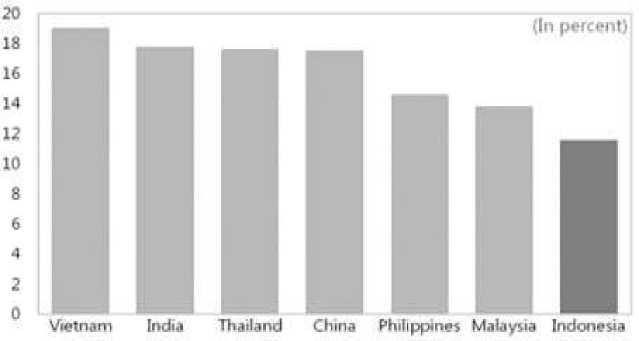

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) Country Report for Indonesia in 2017 (2018, 11) states that Indonesia’s tax-to-GDP ratio has continued to decline in recent years. Based on data from the World Bank, Indonesia’s tax ratio continued to decline from 2012 to 2016, which were 11.38 percent, 11.29 percent , 10.84 percent , 10.75 percent , and 10.33 percent, respectively. The Indonesian tax ratio in 2016 even ranks lowest among developing countries in Asia (IMF, 2018).

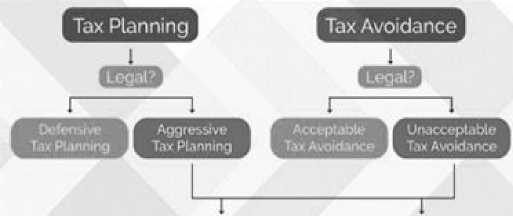

According to Besley & Persson (2014, 109), one of the main factors in low tax revenue in developing countries is the practice of high tax avoidance. Tax is a compelling contribution to the state. In the theory of risk aversion, Allingham and Sanmo believe that no individual is willing to pay taxes voluntarily (Sarjunajuntak & Mukhlis, 2012). Individuals will always oppose paying taxes. In other words, taxpayers will make various efforts to reduce the tax burden so that the net income obtained becomes greater. Efforts to reduce the tax burden are often carried out through aggressive tax planning

practices or tax avoidance practices. According to the Australian Tax Office (2004, 11), aggressive tax planning is the point where tax planning goes beyond the policy intent of the law. Meanwhile, tax avoidance is a manipulation of one ‘s affairs within the law in order to reduce the tax dues (James et al., 1978). According to Deny (2016) Bambang Brodjonegoro, as Minister of Finance at that time, once stated that since the past ten years, 2,000 foreign investment companies (PMA) have not paid taxes. As a result, in this period the country suffered losses of up to Rp. 500 trillion. This condition shows the high practice of tax-avoidance in Indonesia.The General Director of Taxes at the time, Ken Dwijugiasteadi, revealed that those who intended not to pay taxes were those companies not paying Corporate Income Tax (PPh) Article 25 and Article 29 for reasons of continuous loss, even though in fact they still managed to exist from year to year. Ken also stated that Article 25 and Article 29 PPh is the type of tax that is most difficult to withdraw because it is attached to the Agency itself (Ariyanti, 2016).

Figure 1. Tax-to-GDP Ratioin 2016

Source: IMF Country Report No. 18/32 (2018)

Tax avoidance is often interpreted as a transaction scheme aimed at minimizing the tax burden by utilizing the weaknesses (loophole) of a country’s tax provisions (Darussalam, 2017). Brown in Wijaya (2014) states that tax avoidance is the

arrangement of transactions to obtain profits, benefits, or tax deductions in ways that are not desired by tax laws. The relationship between planning, avoidance and tax evasion is explained in Figure 2.

Transfer PncingrTrealy Shopping CFC Thin Capitalization

i

Criminal sanction!

Figure 2. Relationship between Tax Planning, Tax Avoidance and Tax Evasion

Source: Danny Darussalam Tax Center (2018)

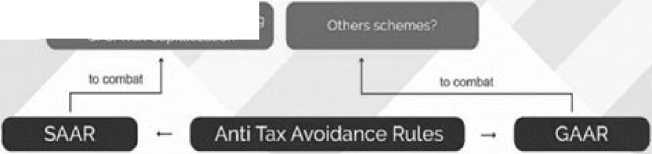

To deal with the practice of tax-avoidance, various countries have compiled and implemented anti-avoidance rules. These rules are specific (Specific Anti Avoidance Rules / SAAR) and / or general (General Anti Avoidance Rules / GAAR). According to Ernst & Young (2013, 2), SAAR is a tax regulation designed to deal with certain transactions of concern. Damian (2013, 48) states SAAR as a specific anti-tax avoidance provision to prevent certain tax avoidance schemes. In the Income Tax Law there are several elaborations on SAAR that apply in Indonesia, namely those intended to deal with certain tax avoidance schemes. for

example such as thin capitalization, controlled foreign companies, transfer pricing, special purpose companies, and treaty shopping.In Indonesia, the SAAR provisions are regulated in Article 18 of Law Number 36 of 2008 concerning the Fourth Amendment to Law Number 7 of 1983 concerning Income Tax (PPh Law) along with the implementing regulations.

In addition to publishing SAAR, several countries have also implemented GAAR to handle tax avoidance practices in their countries, either in the form of doctrines (judicial GAAR) or stated explicitly in statutory GAAR (Arnold, 2008). Finnerty et al. in

Suryani & Devos (2016, 1784) defines GAAR as a domestic regulation that allows the tax authority to re-characterize a series of transactions that have been carried out on sole purpose or main purpose to obtain undue tax benefits. According to Silvani (2013, 7), interpreting GAAR as “an anti-avoidance measure, generally statute based, providing criteria of general application, i.e., not aimed at specific tax payers or transactions, to combat situations of perceived tax avoidance”. Damian in Inside Tax Issue 15 (2013, 48) describes GAAR as a general anti-tax avoidance provision to prevent transactions that are solely aimed at avoiding taxes and have no business motives. In addition, Freedman (2014, 170) outlines five problems that must be considered in the formulation of GAAR are 1) used as an approach to statutory interpretation or overriding principle, Freedman states that GAAR must act as an overriding principle and not just an interpretation of the language of regulation. 2) The objective or objective purpose test should be employed, Freedman states that all tests in GAAR should be objective. Subjective testing often causes problems because evidence is a very difficult problem given the complexity of tax regulations. 3) Burden of proof, There is a different burden of proof approach in every jurisdiction, which can be in the hands of the tax authority or taxpayer. 4) Prescriptive or less detailed, An alternative to the transaction that must be defeated by the GAAR (counterfactual) is needed to know the tax that must be applied. Provisions that are too prescriptive sometimes cause difficulties for the tax authorities in implementing GAAR. Therefore, the GAAR provisions must be designed to be more open, namely in the sense that the tax authority can make fair and reasonable adjustments to the transaction. 5) Relationship with tax treaties, basically, GAAR can be applied even if there is a tax treaty, but the position of GAAR cannot exceed or replace the tax treaty. GAAR can be applied if there are abusive transactions that try to take advantage of certain provisions in the tax treaty or the provisions in other tax regulations.

GAAR is a last resort that can be used by tax authorities to deal with the practice of unacceptable tax avoidance that cannot be imposed with the provisions or interpretation of ordinary tax laws (Waerzegers and Hillier, 2016). In the journal Designing a General Anti-Abuse Rule: Striking a Balance, Freedman (2014, 167) states that GAAR statutory is an important element of the modern taxation system because SAAR will not capture all tax avoidance that occurs. One reason for the

preparation of the GAAR is as a form of anticipation of the practice of tax evasion that has not been regulated in special provisions (SAAR) or to counter the practice of tax evasion which at the time of drafting tax regulations is still unknown. Some countries have implemented GAAR statutory to deal with tax avoidance issues, including Australia, Britain, Singapore, Canada, China, India, New Zealand, the United States, and the European Union. While Indonesia itself still has no GAAR statutory in its tax regulations.According to Waerzegers & Hillier (2016, 1), the success of GAAR in achieving its objectives will depend heavily on (a) the legal design and drafting of the GAAR and (b) the capacity of the tax authority to apply the GAAR in an measured, event handed and predictable way.

A country can freely choose whether to implement SAAR, GAAR, or a combination of both.Generally, GAAR cannot be implemented if SAAR and / or tax treaties apply to the tax avoidance scheme that is disputed. GAAR is a last resort to counter the practice of tax avoidance, in the event that SAAR and / or tax treaties cannot handle it. Anang Mury Kurniawan argues that in dealing with tax avoidance practices in Indonesia ideally, both instruments, both SAAR and GAAR, are needed (Triyanto, 2017). In addition to anticipating new or unknown tax avoidance schemes, GAAR can provide legal certainty over the determination of unacceptable tax avoidance and aggressive tax planning. The disagreement between tax authorities and taxpayers is often caused by the absence of a clear definition in Indonesian tax regulations regarding which schemes can be categorized as unacceptable / acceptable tax avoidance, aggressive / defensive tax planning, or tax evasion.

Previous research that studied the application of GAAR in Indonesia done bySuryani and Devos (2016). This study aims to explore the ideal GAAR design in Indonesia.This research’s results produced several things including the general rules of GAAR, 5 key elements that must exist in the formulation of GAAR in Indonesia, and the relationship between SAAR and GAAR.

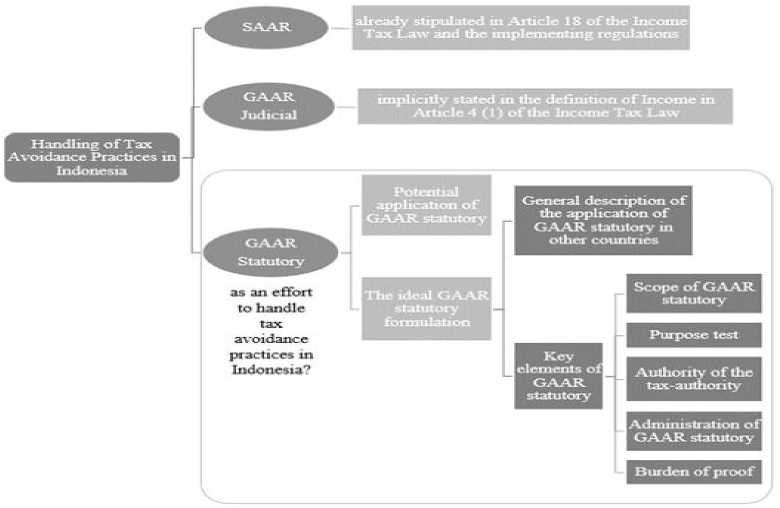

This research is focused on exploring GAAR statutory potential as an effort to handle tax avoidance practices in Indonesia and exploration of GAAR statutory formulas that are ideal to be applied in Indonesia. Exploration of GAAR statutory formulation focuses on the general description of the application of GAAR statutory in other countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, England and India) and five key elements of GAAR statutory

based on the results of Suryani and Devos (2016), namely (1) GAAR statutory scope (in identifying a scheme, GAAR must apply to a combination of transactions which may include the entire arrangement or series of transactions), (2) purpose test (taxpayer’s purpose / intention plays an important role in determining whether a scheme is considered aggressive or not), (3) authority of the tax-authority (the authority possessed by the tax authority on taxpayers who carry out tax avoidance intentionally), (4) GAAR statutory administration (GAAR Administration must include the existence of a GAAR Panel, where the panel is tasked with determining whether a case is relevant to the application of GAAR), and (5) burden of proof (there are different opinions about whether a Taxpayer or tax authority has the obligation to provide evidence).

RESEARCH METHOD

This research was compiled based on a qualitative approach in form of case study. Qualitative research is an approach to exploring and understanding social or humanitarian problems (Creswell, 2014). Morse in Creswell (2014, 20) states that a type of qualitative approach is needed because the research topic is new, the subject is never stated with a particular sample or group of people, and the existing theory does not apply to the particular sample or group studied. In addition, a qualitative approach is carried out because of the need to explore and explain phenomena in depth, where the nature of the

phenomenon is not in accordance with quantitative measures. Furthermore, a case study is conducted to investigate a phenomenon within its real-life context.Whereas according to Sugiyono (2015, 24) qualitative approaches are used in conditions, among others in terms of research problems not yet clear, to understand the meaning behind the visible data, to develop theory, and to ensure the correctness of data. The author uses a qualitative approach in form of case study while conducting this study with the aim of exploring and gaining a deeper understanding of GAAR and its application so that it can produce an overview of the ideal GAAR statutory formulas in Indonesia. In this study, we interviewed 9 Interviewees from various institutions in Indonesia who according to us were indeed competent with this problem. All the following names are pseudonyms. They are, Mr. Jaka (Head of Sub Directorate of Prevention and Handling of International Tax Disputes, Directorate General of Taxes), Mr. Raden (Directorate General of Taxes), Mr. Prabu (Head of the P3B Subdivision of Australia, Asia-Pacific and Africa, Fiscal Policy Agency), Mrs. Kartini (Fiscal Policy Agency), Mr. arjuna (a Tax Partner of Ernst & Young), Mr. Bima (a Tax Partner of Danny Darussalam Tax Center (DDTC)), Mr. Yudhistira(a Senior Researcher from CITA), Mr. Pandu (Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center), and Mr. Dursasana (a lecturer in Politeknik Keuangan Negara STAN). The reserach framework used in this study is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Research Framework

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

GAAR Statutory Potential as Handling Tax Avoidance Practices in Indonesia.Mr. Arjuna (Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young) and Mr. Dursasana (Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN) explained that tax avoidance practices not only occur in Indonesia, but also occur in other countries. Mr. Dursasana explained further that the practice of tax avoidance was primarily motivated by the concept of economics which assumes that everyone is rational, that is, people will choose the best or most profitable alternative from the available choices. Faith also states that taxpayers will carry out tax management or tax avoidance as long as there is an opportunity and along the legal corridor. According to Mr. Arjuna, in general there are four factors that can cause tax avoidance, namely high tax rates, the number of gray areas, the low potential

detected, and the small amount of penalties that will be given.

One proof of the practice of tax evasion in Indonesia occurred in 2016. Bambang Brodjonegoro, Minister of Finance in 2016, once stated that there were 2,000 foreign investment companies in Indonesia that had not paid taxes within the past ten years with potential state losses of 500 trillion rupiah (Deny, 2016). Mr. Pandu(Tax Education and Training Center Lecturer) states that tax avoidance practices are also increasingly varied. The avoidance mode which initially only relates to passive income (such as dividends, interest, royalties) has begun to shift to active income (such as Base Erosion and Profit Shifting / BEPS).

Table 1 below shows a matrix of interview results regarding the urgency of applying GAAR statutory in Indonesia.

Table 1. Urgency of the Application of GAAR Statutory in Indonesia

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

The existence of GAAR statutory is important becau will become a legal basis. |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

GAAR statutory is a policy problem. The presenc absence of GAAR statutory has a positive and nega impact respectively. |

|

Prabu, Fiscal policy Agency |

GAAR statutory is needed to assist tax authoritie enforcing rules for prevention of misuse of Tax Tr and other taxation. |

|

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency |

GAAR statutory is intended to accommodate limitations of regulators when a tax avoidance sch does not yet exist. |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young |

Precisely before owning SAAR, the tax authority sho already have GAAR statutory first. |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC |

GAAR Statutory is needed in Indonesia. The tax autho will not be missed in the case of Google and several o cases if the GAAR statutory has been implemented. |

|

Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher |

GAAR is needed to handle tax avoidance practice Indonesia. GAAR must be affirmed in law and not me based on the examiner's interpretation or discretion. |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center |

Statutory GAAR has advantages for things that anticipatory in nature, but on the other hand it can als a 'pasalkaret’ which causes low legal certainty. |

|

Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

GAAR statutory can be an effort to handle tax avoida practices in Indonesia, but it must also be considered impact on the economy and investment. |

Source: Data Processed, 2019

Ideal GAAR Statutory Formulation in Indonesia. Waerzeggers and Hillier (2016, 1) state that the ultimate goal of a GAAR is to eradicate unacceptable tax avoidance practices. The success of GAAR in achieving its objectives will depend on the design and formulation of its laws and the capacity of the

tax authorities to implement GAAR appropriately in a way that is measurable, fair and predictable. GAAR statutory must be designed to suit the legal background of the jurisdiction in question (Freedman, 2014). The results of Suryani and Devos (2016, 1786) in The Proposed Design of an Indonesian General

Anti-Avoidance Rule, five key elements that must be included in the formulation of GAAR statutory are (1) GAAR statutory scope, (2) purpose test, (3) authority of the tax-authority, (4) GAAR statutory administration, and (5) the burden of proof.

Cooper (2001, 98) says “the first and most obvious requirement is a provision that defines the trigger for activating the GAAR”. That is, determining whether the GAAR statutory target is a matter of intent (taxpayer intentions), matter of form (scheme form), or a combination of both.Based on the results of interviews with the Interviewees, in general there are three opinions regarding the trigger when GAAR statutory should activate, they are (1) a combination of matter of intent and matter of form. The majority of Interviewees argue that GAAR statutory can be triggered by these two factors. (2) The impact of the scheme. Raden (2018) argues that in the activation of GAAR, the first view is not from the side of intensity, but from the impact first. Tax authorities must see whether there are tax benefits obtained by taxpayers that are not obtained by other taxpayers in ways that are not permitted by the tax authorities. (3) Purpose of the scheme. Bima (2018) argues that the focus of GAAR is on the principle of

the tax avoidance scheme. To find out the purpose can be used an analysis similar to transfer pricing analysis, whether the Taxpayer has the capacity to bear the risks and functions that he must do.

In identifying a scheme, GAAR statutory must apply to a combination of transactions that can cover all arrangements or series of transactions (Suryani and Devos, 2016). GAAR is intended to prevent abusive tax avoidance transactions, but not to be applied to legitimate commercial transactions (Arnold, 2017). With this, GAAR must be able to distinguish between the two types of transactions. Kartini (2018) explains that one of the OECD recommendations in the application of GAAR statutory is the existence of GAAR guidelines. The GAAR guidelinesprovides a list or examples of transactions that can be applied to GAAR and commercial transactions that are considered legitimate.

Tax Benefits Based on the results of our interviews, Jaka, Raden, Yudhistira and Dursasana explained the definition of substantive tax benefits. While Prabu, Arjuna, Bima, and Pandu outlined some general forms of tax benefits.

Table 2. The Definition of Tax Benefit

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

Actually, all tax planning and tax avoidance are essentially getting tax benefits. |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

Every incident that makes the tax of the tax-payers more profitable compared to the absence of these tax benefits. For example, lower taxes, tax credits and compensation for losses that should not be obtained. |

|

Prabu, Fiscal policy Agency |

The general forms include tax delays, tax abolition, tax reduction (reducing costs or not paying taxes at all). |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young |

The tax becomes smaller or none at all, the tax becomes delayed, and the level of certainty of the cost reduction becomes more certain. |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC Yudhistira, Senior Reseracher on CITA |

Tax holiday, differences in rates, matters related to recognition of income and costs. Tax benefits mean effectively the overall tax in the whole world is smaller. For example, shifting income or costs from one country to another, which rates are lower or none at all (by characterizing such transactions). |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

Lower rates, facilities, tax exemptions. Substantially are:

|

Jaka (2018) states that GAAR statutory must be applied selectively. The target is certain tax avoidance cases whose impact is large and cannot be reached by SAAR. Based on the results of interviews with the Interviewees, there are two opinions regarding the need for a monetary threshold in the GAAR statutory formulation that is ideal in Indonesia. The first opinion according to Arjuna and Kartini, the monetary threshold is not required in the GAAR statutory formula because the materiality of tax avoidance should be left to the assessment of the tax examiner. The second opinion aside from Arjuna and Kartini states that monetary threshold is needed in the formulation of GAAR statutory.

Based on the results of the author’s interview regarding the nature and shape of the purpose test that should be applied in GAAR statutory in Indonesia, most of the Interviewees stated that the purpose test is a combination of objective and subjective testing. As for the form of the ‘purpose test’, the Interviewees were divided into three opinions, there were those who argued that neutral in other words did not question the form, some argued using the main purpose test which investigated the main purpose of tax avoidance. While the third opinion, states that the form should be a one-of-a-purpose test which has a wider range than the main purpose test.

Table 3. Characteristics and Forms of Purpose Test

|

Interviewees |

Characteristics of the Purpose Test |

Forms of the Purpose Test |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

Neutral |

Neutral |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

objective testing |

Neutral |

|

Prabu, Fiscal policy Agency |

combination of objective and subjective testing |

One of the main purposes |

|

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency |

combination of objective and subjective testing |

Main purpose |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young |

combination of objective and subjective testing |

Neutral |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC |

objective testing |

Main purpose |

|

Yudhistira, senior researcher at CITA |

combination of objective and subjective testing |

Main purpose |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center |

objective testing |

One of the main purposes |

|

dursasana , Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

objective testing |

One of the main purposes |

Source: Data Processed, 2019

Authority of the Tax-Authority

One important part of GAAR statutory is a provision that allows tax authorities to reverse the tax that has already occurred and replace it with one of the possible taxes that should occur (Cooper, 2001). One of the Interviewees argued that in implementing the GAAR statutory ideally a separate

GAAR Panel should be formed. This is because GAAR statutory is a wide-ranging ultimatum. If there is no special panel, it is feared that there will be a lot of moral hazard, where the tax examiner will arbitrarily apply GAAR if there is no finding. The opinion of the Interviewees regarding the authority of the tax authority is presented in Table 4 below.

Interviewees

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC

Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax

Training Center

Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of

Finance STAN

Opinion

-

- Cancel the tax benefits

-

- Give sanctions

Cancel tax benefits

Ideally a GAAR Panel should be formed

-

- Characterize transactions

-

- Recalculate the tax payable

-

- Reviewing tax avoidance schemes

-

- Give sanctions

-

- Make corrections

-

- Characterize transactions

It depends on how the tax authorization authorit model is desired by the Minister of Finance

GAAR statutory is a potentially powerful tool for the tax authority to fight tax avoidance. Taxpayers and tax consultants are concerned that GAAR will be applied indiscriminately and used as a threat to tax more than it should pay (Arnold, 2017). Therefore, GAAR must be designed as a ultimate effort that is not implemented at all times and can only be applied if other provisions in the tax regulations cannot reach or handle the case. In order for the authority and / or discretion of the tax authority in the application of GAAR statutory to be not too broad, some Interviewees provided recommendations to limit it.

First, Raden and Pandu stressed the importance of the threshold and the determination of authority to activate GAAR statutory. According to Pandu, GAAR should only be applied to large cases or cases that deserve widespread attention from the public. Raden previously also explained that the existence of a threshold could focus the efforts of the tax authorities on material transactions. Related to the determination of authority to activate GAAR statutory, Raden and Pandustated that not all examiners or the lowest level of tax authorities can activate GAAR. This authority must be owned by higher level authorities. Secondly, Raden, Prabu and Yudhistira emphasized the preparation of the rules of the game or the procedure for applying GAAR statutory that was clear so that the tax authorities did not take too much initiative or understanding themselves. Third, Raden and Prabu also argue that the formation of the GAAR Panel also plays an important role in limiting the authority and / or discretion of the tax authority that is too broad. Each panel member cannot arbitrarily make decisions because decisions are taken together. Finally, Arjuna stated the importance of using information disclosure. In conducting checks, the tax authority can compare data and information in SPT reported by Taxpayers with those obtained from third parties. Different numbers will be the focus of the examination so it doesn’t widen everywhere.

GAAR statutory is a provision of last resort. Like other anti-avoidance rules, GAAR must be applied by tax authorities and not by taxpayers even in the self assessment system (Arnold, 2017). The application of GAAR statutory by the tax-authority must be in accordance with the general inspection procedures of the taxation systems of each country. However, some special provisions may be required in GAAR-based examinations. The majority of Interviewees agreed that the application of GAAR

statutory must be carried out in the context of tax audits.

Arjuna has a different opinion from other sources regarding the timing of the application of GAAR statutory, “The testing is done at a certain time, because if we use the SPT it will also not be found out. SPT is a global number. Just an audit report with the numbers in P / L (Profit / Loss), and even then, it’s still not visible “. According to Arjuna, the business scheme reported by Taxpayers in connection with MDR can be tested with GAAR statutory to assess whether the scheme includes tax avoidance or not. However, Raden looked at MDR as a prevention effort. Even though it can be used as an ingredient to activate GAAR statutory, in MDR there are no transactions that can be corrected because Taxpayer disclosures are made before the transaction occurs. According to Yudhistira, the application of GAAR statutory through tax audit procedures is actually an effective step because at the time of inspection the tax authority will conduct an analysis of all relevant Taxpayer transactions. Examinaation procedures within the GAAR statutory should not be included in the usual inspection because generally the proof will be more difficult so that it requires a longer period of time (Pandu, 2018).

One of the Interviewees argued that the authority to implement statutory GAAR in Indonesia must consider the human resource capacity of the tax authority. The Directorate General of Taxes must be able to guarantee the same quality standards for decision making, if the application of GAAR is imposed at each level of the tax service office. In addition, the application of GAAR in the international tax regime ideally uses a panel, committee, or board of director (BOD). Initially a tax audit can be done at the tax service office, but when entering the GAAR domain, a panel that reviews the application of GAAR is needed. Table 5 below presents a summary of the opinion of the Interviewees regarding the authority in applying the GAAR.

In some countries, the application of GAAR statutory is recognized as a very significant matter so that the government forms a panel whose task is to supervise or provide advice regarding its implementation (Ernst & Young, 2013). The GAAR Administration must involve an independent consultation panel to ensure consistency, fairness and equality for taxpayers. Arnold (2017, 751) states that the application of GAAR statutory can be the subject of determination by the panel. With this, tax auditors

|

Table 5. Authorities to Implement GAAR Statutory | |

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

GAAR Panel |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

GAAR Panel |

|

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency |

GAAR Panel |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & |

Regional offices and head office based on certa |

|

Young |

thresholds |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC |

Depends on the capacity of human resources at t Directorate General of Taxes |

|

Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher |

Regional Office |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center |

Headquarters |

|

Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

Tax service office and regional office |

Source: Data processed, 2019

who want to apply GAAR statutory will be asked to submit the case to the panel. The tax inspector must provide a detailed explanation of the transaction and the reason why GAAR statutory must apply. Assessment based on GAAR statutory will be issued only if the panel approves its application in the case. This process can provide taxpayers with confidence that GAAR statutory is applied fairly and consistently. Freedman (2014) states that GAAR

panel membership can involve external parties outside the tax authority. Although it can improve objectivity and consistency, the participation of external parties can also raise concerns about confidentiality and conflicts of interest of taxpayers. All interviewees we interviewed agreed to state that GAAR panels are needed in the application of GAAR statutory in Indonesia.

Table 6. GAAR Panel

|

Interviewees |

Urgency of Forming GAAR Panel |

Panel Membership |

Authority |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) |

mandatory |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) |

mandatory |

|

Prabu dan Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency |

Necessary |

Depends on the wishes of policy makers |

mandatory |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) and external (chamber of commerce) |

mandatory |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) and external (academics, business practitioners) |

advisory |

|

Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher |

Necessary, can be combined with the quality assurance inspection team |

Internal (tax-authority) and external (academics, business practitioners) |

mandatory |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) |

mandatory |

|

Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

Necessary |

Internal (tax-authority) |

mandatory |

Source: Data Processed, 2019

Arnold (2017) states that the imposition of sanctions or penalties in connection with the application of GAAR statutory can be considered reasonable and necessary for the effectiveness of

GAAR. Tax penalties applicable in Indonesia are regulated in Law No. 28 of 2007 concerning the Third Amendment to Law No. 6 of 1983 concerning General Provisions and Procedures for Taxation (UU

KUP), but no article specifically regulates sanctions for tax avoidance practices. Taking into account the violations that occur are intended for tax avoidance (Yudhistira, 2018 and Arjuna, 2018) or in other words

they are more than administrative violations (Raden, 2018), the sanctions set should be greater than the current sanctions in the KUP Law so that they can provide a deterrent effect.

Table 7. Sanctions for the Application of GAAR Statutory

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes Raden, Directorate General of Taxes Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

Specific Sanction Specific Sanction Specific Sanction Specific Sanction Specific Sanction Specific Sanction General sanctions, as stipulated in the UU KUP Specific Sanction |

Source: Data processed, 2019

All tax jurisdictions have SAAR which can operate side by side with GAAR (Krever, 2016). Regarding the relationship between GAAR and SAAR statutory that applies in Indonesia, all speakers have the same view, namely ‘adagiuml exspecialis derog at legigenerali’, the application of SAAR must take precedence over GAAR statutory. Raden stated that in the event the transaction has been handled with SAAR, it cannot be corrected again using GAAR statutory. If it is not regulated in SAAR or other tax provisions, GAAR statutory can be applied.

SAAR and GAAR statutory are included in the realm of a country’s domestic tax regulations. The relationship between GAAR statutory of a country and tax treaty depends on how the tax authorities and the court interpret the tax agreement (Arnold, 2017).

Based on Article 32A of the Income Tax Law, the Government has the authority to enter into agreements with other countries’ governments in the context of double tax avoidance and prevention of tax evasion. Furthermore, in the explanation of Article

Table 8. Relationship between Statutory GAAR and Tax Treaty

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

GAAR is a domestic regulation so that it has nothing to do with tax tre If anyone misuses the tax treaty, taxpayers cannot also request MAP. According to the OECD, tax treaty does not hinder the applicatio GAAR. GAAR can conduct a characterization before applying the treaty. If the tax treaty already has GAAR or PPT and LOB, then it is b to apply the tax treaty first. |

|

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher |

Tax treaty in Indonesia is lex specialis. Tax authorities can apply dome regulations if taxpayers use loopholes in the tax treaty. Tax treaty can override domestic regulations. It cannot be if it contrad the tax treaty then returns to GAAR again. Tax treaty can be used to determine taxation rights after being character by GAAR. Tax treaty can overlap with GAAR related to PPT. Tax treaty takes precedence over domestic regulations. But if transaction utilizes a loophole, as long as it is not regulated in the tax tre the GAAR can apply. |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

GAAR can only apply if the tax treaty cannot be used. If taxpayers ut loophole tax treaty, it means that GAAR can apply. The tax treaty is lex specialis. |

32A, in the context of increasing economic and trade relations with other countries, a special legal instrument (lex specialist) is required to regulate taxation rights from each country in order to provide legal certainty and avoid the imposition of double

taxation and prevent tax evasion. With this, it is stated clearly that the tax treaty in Indonesia is lex specialis. The following are the results of our interview with the speakers about the relationship of GAAR Statutory and Tax Treaty in Indonesia.

Table 9. Burden of Proof

|

Interviewees |

Opinion |

|

Jaka, Directorate General of Taxes |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Raden, Directorate General of Taxes |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Kartini, Fiscal policy Agency |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Arjuna, Partner of Tax Service Ernst & Young |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Bima, Partner of Tax Service DDTC |

Tax authorities |

|

Yudhistira, CITA senior researcher |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Pandu, Lecturer at Widyaiswara Tax Training Center |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

|

Dursasana, Lecturer at Polytechnic State of Finance STAN |

Tax authorities and taxpayers |

Source: Data processed, 2019

Freedman (2014) explains that the burden of proof is often a problem in the discussion of GAAR statutory. Based on the results of the interview (Table 9), the majority of the interviewees argued that the burden of proof should be shared between the tax authorities and taxpayers. The only interviewee who has a different opinion is Bima. He stated that the burden of proof should only be in the tax authority. Even though taxpayers can reject or refute the opinion of the tax authority, it does not mean the burden of proof goes to taxpayers. The burden of proof can be in the Taxpayer if the Taxpayer does not do bookkeeping, does not report, or does not disclose what is requested in the inspection process.

The tax regulation reform program currently being implemented by the Government is the right momentum to formulate GAAR statutory. The current anti avoidance rules are deemed unable to catch up with the development of business activities and the avoidance mode which is so fast that many tax avoidance cases escape the law. Based on this background, the majority of informants agreed that the GAAR statutory be formulated and applied in Indonesia. Statutory GAAR is a last resort in handling tax avoidance practices, meaning that GAAR statutory can only be applied if SAAR cannot be used in such cases. Statutory GAAR should also be directed to handle tax avoidance practices that are very material and have a big impact. The GAAR statutory legal design must be carefully formulated in order to provide legal certainty for taxpayers and tax authorities.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of the analysis and discussion, we can conclude that the application of GAAR statutory is one of the potential efforts to deal with the practice of tax avoidance in Indonesia that is very effective. With this research, we try to formulate GAAR statutory that is ideal to be applied in Indonesia. Our suggestions for the future, both for the Tax Authorities in Indonesia and for future researchers, are to be able to make the best use of this research to improve the existing system. Although the selection of our interviewees still does not represent the perspective of all stakeholders related to handling tax avoidance practices. The following are G The Ideal GAAR statutory formula in Indonesia covers five elements including GAAR statutory scope, Purpose test, Tax authority, GAAR statutory administration and Burden of proof.

The first element on this formula is GAAR statutory scope which covers three key points. First, GAAR statutory targets are complex and high-impact transactions, with this GAAR statutory must be applied to a combination of transactions that can cover the entire arrangement or series of transactions. Statutory GAAR must also be able to distinguish between abusive tax avoidance transactions and legitimate commercial transactions. The active trigger for GAAR statutory is a combination of matter of intent (intention of the Taxpayer) and matter of form (form of the scheme). The intention of the taxpayer is subjective so it is difficult to prove, while the form of the scheme will be easily deceived and fabricated.

Therefore, the active GAAR statutory can be triggered by both. In activating the GAAR statutory, the tax authority should also consider aspects of the spirit of the law.

Second, Statutory GAAR aims to ward off transactions that have a purpose to obtain undue tax benefits. The definition of undue tax benefits will become evergreen dispute between the taxpayer and the tax authority. Tax authorities can have the perception that a tax benefit should not be obtained by the Taxpayer, but the Taxpayer can have a different opinion. Basically, tax benefits are any event that makes the taxpayer’s tax position to be more favorable than the absence of the tax benefits. In other words, tax benefits are things that in theory can cause a reduction in the basis for taxation or things that cause taxpayers’ profits to be inconsistent with their functions, assets, and risks. Third, Statutory GAAR must be applied selectively, meaning that it is targeted at tax avoidance schemes that have a large impact and cannot be reached by SAAR. One way is through monetary threshold provisions on the tax benefits or the value of the tax payable. The monetary threshold actually facilitates the administrative requirements of tax authorities and forms the efficiency of compliance costs so that the application of the statutoryGAAR can be focused on cases of significant or material tax avoidance.

Next, the second element on The Ideal GAAR statutory formula is Purpose test. The Purpose tests must be objective, i.e. consider objective facts that are relevant to the purpose of the transaction. The intention of the taxpayer (subjective) can also be considered, but the conclusion of the purpose test is still carried out objectively. Related to the purpose test form, there are two variations of forms that can be considered, namely the main purposes test and the one of the main purposes test (one of the main objectives. The choice of the purpose test form is adjusted to the extent of the GAAR statutory application desired by tax authority The sole purpose test is considered the least likely because proof of the sole purpose of tax avoidance will be very difficult.

Next, The third element on The Ideal GAAR statutory formula is Tax authority. Generally, the authority that tax authorities must have in implementing the GAAR statutory is to cancel tax benefits for abusive tax avoidance practices. The tax authority can also be given additional authority, such as carrying out the characterization of the transaction and imposing sanctions. One way that the authority or discretion granted to the tax authority

is not too broad is to provide clear rules or procedures for applying the GAAR statutory.

Furthermore, the fourth element on The Ideal GAAR statutory formula is GAAR statutory administration.This element including some points. first, The application of the GAAR statutory must be carried out in the context of a tax audit. Statutory GAAR can only be applied if the tax avoidance scheme is not included in the SAAR scope. Second, as GAAR statutory is a last resort, approval of the application of GAAR statutory must be at the high level authority. For example at the regional office level, at the head office level, or at the GAAR Panel. Third, to increase the effectiveness of GAAR statutory application, a special panel is needed. The GAAR Panel membership ideally should not only come from internal parties (tax authorities), but also from external parties. The selection of members from external parties must be very selective because neutrality must be ensured. There must not be conflicts of interest and threats to the confidentiality of taxpayer data. Best practice regarding GAAR’s authority The panel is authorized to determine whether GAAR’s statutory is applicable to a tax avoidance scheme. fourth, Because it is intended for tax avoidance or in words other than administrative violations, the sanctions in the application of the GAAR statutory should be greater than the sanctions in force in the current KUP Law. The existence of larger sanctions is expected to provide a deterrent effect to the Taxpayer. The fifth, based on Indonesian law, SAAR and tax treaty are lex specialis against GAAR statutory. Therefore, SAAR and tax treaty must be applied first. However, as stated in the OECD Commentary on Article 1, the GAAR statutory can characterize a transaction before taxation rights are determined by a tax treaty.

The last element The Ideal GAAR statutory formula is Burden of proof. The burden of proof in the application of the GAAR statutory is shared between the tax authority and the taxpayer. The tax authority must prove that the purpose transaction is to avoid tax or enter in GAAR statutory criteria. Meanwhile, taxpayers must also be given the opportunity to prove the opposite (the purpose of the transaction is bona fide). AAR statutory design recommendations according to the Author.

The researcher realizes that the selection of informants still does not represent the viewpoints of all stakeholders relating to the handling of tax avoidance practices. Some speakers also did not fully master the best practices of the GAAR statutory application. The researcher can then consider the

selection of speakers who truly have competence regarding anti avoidance rules. In addition, further researchers can also conduct preliminary research in vertical units to determine the effectiveness of anti-avoidance rules that already apply and the urgency of GAAR statutory needs in the field. The researcher can then choose vertical units that have significant tax potential, such as Large Taxpayer Tax Office, Foreign Investment Tax Office, and Medium Tax Office.

REFERENCES

Alink, M., & Van Kommer, V. (2016). Handbook on Tax Administration (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: IBFD Publications.

Ariyanti, F. (2016). Perusahaan Asing Gelapkan Pajak Selama 10 Tahun. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from Liputan6.com website: https:// www.liputan6.com/bisnis/read/2469089/2000-perusahaan-asing-gelapkan-pajak-selama-10-tahun?utm_expid =.9Z4i5yp GQeGiS7w9arwTv Q.0&utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww. google.co.id%2F

Arnold, B. (2008). A comparison of statutory general anti-avoidance rules and judicial general antiavoidance doctrines as a means of controlling tax avoidance: Which is better? (What would John Tiley think?). In J. Avery Jones, P. Harris, & D. Oliver (Eds.), Comparative Perspectives on Revenue Law (pp. 1–24). https://doi. org/ 10.1017/CBO9780511585951.003

Arnold, B. J. (2017). The Role of a General AntiAvoidance Rule in Protecting the Tax Base of General Anti-Avoidance Rule Is a GAAR Necessary/ ? Is a GAAR Necessary/ ? Major Features of a GAAR. In A. Trepelkov, H. Tonino, & D. Halka (Eds.), United Nations Handbook on Selected Issues in Protecting the Tax Base of Developing Countries – Second Edition (2nd ed., pp. 715–754). New York: United Nations.

Ault, H. J., & Arnold, B. J. (2017). Protecting the Tax Base of Developing Countries: An Overview. In A. Trepelkov, H. Tonino, & D. Halka (Eds.), United Nations Handbook on Selected Issues in Protecting the Tax Base of Developing Countries – Second Edition (2nd ed., pp. 1–33). Retrieved from http:// www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2017/ 08/handbook-tax-base-second-edition.pdf

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2014). Why do developing countries tax so little? Journal of Economic

Perspectives, 28(4), 99–120. https://doi.org/ 10.1257/jep.28.4.99

Cooper, G. (2001). International Experience with General Anti-Avoidance Rules. SMU Law Review, 54(1), 83–130.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches: 4th edition. In Organizational Research Methods (Vol. 6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2

Darussalam. (2017). Ini Beda Tax Planning, Tax Avoidance, dan Tax Evasion. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from news.ddtc.co.id website: https://news.ddtc.co.id/perencanaan-pajak-ini-beda-tax-planning-tax-avoidance-dan-tax-evasion-9750

Deny, S. (2016). Dirjen Pajak Diminta Usut Dugaan 2.000 PMA Mangkir Bayar Pajak - Bisnis Liputan6.com. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from liputan6.com website: https://www.liputan6.com/bisnis/read/2471851/dirjen-pajak-diminta-usut-dugaan-2000-pma-mangkir-bayar-pajak

Ernst & Young. (2013). GAAR rising: Mapping tax enforcement’s evolution. Ernst & Young.

Freedman, J. (2014). Designing a general anti-abuse rule: striking a balance. Asia-Pacific Tax Bulletin, 20(3), 167–173.

Freedman, J. (2016). General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAARs) A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS Tax World? The UK GAAR. In GAARs - A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS World (pp. 1–24). https://doi.org/ 10.2139/ssrn.2769554

International Monetary Fund. (2018a). Indonesia: 2017 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Indonesia. In IMF Staff Country Reports (Vol. 18). https://doi.org/10.5089/ 9781484340622.002

International Monetary Fund. (2018b). Indonesia: Selected Issues; Country Report No. 18/33; December 21, 2017 (Vol. 18). Washington D.C.

James, S., Nobes, C., & Economie, B. (1978). Economics of taxation (1st ed., Vol. 1). Oxford: Philip Allan.

Krever, R. E. (2016). General Report, GAARs – A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS World. In M. Lang, J. Owens, P. Pistone, A. Rust, J. Schuch, & C. Staringer (Eds.), GAARs – A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS World (pp. 1–20). Amsterdam: IBFD Publications.

Office, A. T. PS LA 2005/24 - Application of General Anti-Avoidance Rules. , Pub. L. No. PS LA 2005/24 (2016).

Prasetyo, K. A. (2013). Penggelap Pajak, Awas!! InsideTax Media Tren Perpajakan (Di Balik Suap Pajak), 15, 62–65.

Richard Krever, & Mellor, P. (2016). Australia: General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAARs) – A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS World. In M. Lang, J. Owens, P. Pistone, A. Rust, J. Schuch, & C. Staringer (Eds.), GAARs – A Key Element of Tax Systems in the Post-BEPS World (pp. 45–64). Retrieved from https:/ /www.researchgate.net/publication/304749913_ Australia_General_Anti-Avoidance_ Rules_GAARs_-_A_Key_Element_ of_Tax_ Systems_in_the_Post-BEPS_World

Silvani, C. (2013). GAARs in Developing Countries (1st ed.). Retrieved from https://books. google.co.id/books/about/GAARs_in_ Developing_Countries.html?id=iMpisw EACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Simanjutak, T. H., & Mukhlis, I. (2012). Dimensi Ekonomi Perpajakan dalam Pembangunan Ekonomi (1st ed.). Depok: Raih Asa Sukses.

Sugiyono. (2012). Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif, dan R&D (4th ed.). Bandung: Alfabeta

Suryani, N. E., & Devos, K. (2016). The Proposed Design of an Indonesian General AntiAvoidance Rule. World Applied Sciences Journal, 34(12), 1783–1789. https://doi.org/ 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2016.1783.1789

Tretola, J. (2017). Comparing the New Zealand and Australian GAAR. Revenue Law Journal, 25(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.2139/ ssrn.3106522

Triyanto, H. U., & Zulvina, S. (2017). Analisis Perumusan Kebijakan Mandatory Disclosure Rules Sebagai Alternatif Dalam Mengatasi Praktik Penghindaran Pajak Di Indonesia. Jurnal Pajak Indonesia, 1(1), 1–10.

Waerzeggers, C., & Hillier, C. (2016, January). Introducing A General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR). Tax Law IMF Technical Note, 1(01), 1–10.

Wijaya, I. (2014). Mengenal Penghindaran Pajak. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from https:// www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140726022710-57653111-mengenal-penghindaran-pajak-tax-avoidance.

Discussion and feedback