Implementation of constructed wetland technology as a nature-based solution for environmental improvement at the upper reach of the Moskva River

on

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BIOSCIENCES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY ∙ Vol. 1 No. 1 ∙ February 2023

eISSN: 2655-9994

pISSN: 2303-3371

https://doi.org/10.24843/IJBBSE.2023.v01.i01.p06

IMPLEMENTATION OF CONSTRUCTED WETLAND TECHNOLOGY

AS A NATURE-BASED SOLUTION FOR ENVIRONMENTAL

IMPROVEMENT AT THE UPPER REACH OF THE MOSKVA RIVER

Shmonin Kirill1*, Korshunova Natalia1, Derevenec Elizaveta1, Volkova Veronica1 Lazareva Maria1, Denisova Olga1, Barbashin Daniil1, Bondar Zlata1,

Kharitonov Sergey1

-

1 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia *Corresponding author: knshmonin@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Received:

7 December 2022

Accepted:

16 January 2023

Published:

28 February 2023

Moskva River is an important freshwater ecosystem for the capital region of Russia but is under the constant anthropogenic influence that, to many extents, harms its water quality. A solution has been proposed to improve the river water quality with constructed wetlands in the suburbs of Moscow. The model settlement was Ilyinsky, with a population of 500 living near the river. Wastewater volume, pollutant concentration, and mass flow rate were calculated. Furthermore, local terrains and Russian legal requirements were considered in formulating the design. Based on current river water conditions, it is necessary to build a vertical flow constructed wetland with an area of at least 3.94 m2 per person. It was also estimated that treatment efficiency and pollutant flow into the river would decrease, which should lead to improved water quality at the monitoring point ’Rublevo’. In addition, the research found other small settlements without access to sewage treatment plants. After data extrapolation, introducing the constructed wetlands will expectedly lead to higher-quality water on the Rublevo section. For instance, TSS will decrease from 20.88 to 5.93 mg/l, Total Nitrogen from 1.71 to 0.21 mg/l, and BOD5 from 211 to its natural value—a similar potential change is observed from NH4 + (currently, 0.07 mg/l) and Total Phosphorus (0.16 mg/l). In conclusion, the implementation of the constructed wetlands in the region can improve water quality.

Keywords: wastewater treatment, water quality, nature-based solutions

INTRODUCTION

Rivers play a significant role in people's lives. In addition to shaping the

geography of the population (Mackay, 1945), this surface water is a source of

fresh water for living organisms and agriculture (Lawton and Wilke, 1979) and part of the transport infrastructure (Notteboom et al., 2020). People also use rivers for their needs, which can negatively affect ecosystems and the varied benefits they provide to humans. This impact manifests in many forms like pollution (Zhang et al., 2021)—e.g., light pollution (Jechow and Hölker, 2019) and thermal pollution (Miara et al., 2018), hydrological changes (Pokhrel et al., 2018), and invasive species (Coulter et al., 2018). It is exerted by various sources of anthropogenic pollutant loads. For instance, water quality degradation often results from land use change (Razali et al., 2018), urbanization (McGrane, 2016), and treated and untreated effluent (Martínez-Santos et al., 2018). These pollutant sources are typical for the Moskva River.

In recent years, the river’s environmental conditions have shown signs of deterioration (Shchegolkova et al., 2018), encouraging scientists to perform water quality studies and analyze pollutant sources. Nevertheless, the upper course of the Moskva River is underresearched, even though its water quality and biodiversity regulate the river’s self-purification (Yustiani et al., 2018) and ecosystem sustainability (Kraft,

-

2006) . Moreover, inadequate sustainable water treatment infrastructure and high development rates make this area the most environmentally vulnerable. Implementing new sewage treatment plants and other related technological advancements is believed to improve water quality and environmental conditions (Brion et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, to reduce human-caused environmental damage and preserve the river’s ability to self-purify, this study carefully examined and introduced nature-based solutions.

One of the promising treatment technologies is constructed wetlands. Constructed wetlands (CWs) make use of natural processes involving wetland vegetation, soils, and their associated microbial assemblages to improve water quality. Modern studies reported that constructed wetlands could restore river water quality (Kadlec and Hey, 1994; De Ceballos et al., 2001; Jing et al., 2001; Kennedy and Mayer, 2002; Sheng-Bing et al., 2007; Tu et al., 2013). However, this technology is not used in Russia despite its successful application in other countries, including those with similar climatic conditions. Accordingly, the study was intended to evaluate the possibility of using constructed wetland

technology to improve the ecological state of the Moskva River. To achieve this goal, a model site was selected by taking into account various available data on the environment, anthropogenic impact, and geographical location and calculating possible changes in the water quality based on a scenario if the designed and constructed wetlands are used throughout the watershed.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Description of the object

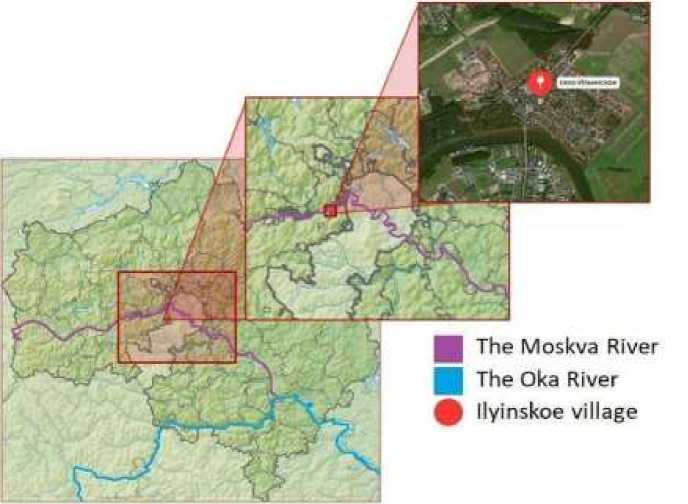

The research object is the Moskva River, which flows through the most populated areas in the Russian Federation: the Moscow region and the City of Moscow. It has a length of 473 km and drains an area (river basin) of 17640 km2 (Озерова, 2014). The Moskva River has 92 tributaries and is itself a tributary of the Oka River. The Oka River flows into the Volga River before emptying into the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest lake as seen in Figure 1.

The Moskva River flow is fully regulated, resulting in no seasonality in a moderately-cold climate regime. This is crucial for sustaining its functions in, among others, flood safety, water provision (incl. drinking water source), navigation (as a transportation system’s artery), and electricity generation.

eISSN: 2655-9994 pISSN: 2303-3371 https://doi.org/10.24843/IJBBSE.2023.v01.i01.p06

However, the river is polluted due to byproducts of industrial and agricultural activities and treated wastewater from municipal treatment facilities. Its significance for the region and the specific anthropogenic impacts makes the river unique in many ways.

Data collection and analysis

The study is based on secondary data and literature (Shchegolkova et al., 2018; Eremina et al., 2016; Yashin et al., 2015) that provide actual and detailed information on the river’s environmental conditions, hydrological regime,

anthropogenic pollution, and many others.

The environmental monitoring database of the Moskva River received from Natalia Schegolkova (Shchegolkova et al., 2018) and reports produced by the Moscow Natural Resource Management and Environment Department (Moscow Government, 2019) were used to assess the river’s environmental state and hydrological regime. Then, after performing the initial analysis, the river was divided into three segments for further analysis as seen in Table 1.

Based on the hydrological and anthropogenic indicators, the ‘Upstream Moscow’ was selected for the constructed wetland location. This segment has more accessible territories, a significant

contribution to the river’s environment, and major problems with the water treatment infrastructure.

Figure 1. Moskva River and its positions in Russia’s river system (Ozerova, 2014)

Table 1. Divisions of the Moskva River and their characteristics

|

Indicators |

Upstream Moscow Within Moscow Downstream Moscow |

|

Building density |

Low High Medium |

|

Building density growth |

High - Medium |

|

Water quality |

High High to low Medium |

|

Water inflow |

Low Medium High |

|

Self-purification intensity |

High Low Medium |

|

Share of untreated domestic wastewater |

High Low Medium |

Selecting a model settlement

The model settlement, where the constructed wetland structure was built, should meet six criteria. (1) The settlement should be in the ‘Upstream Moscow’ segment. (2) The distance to the river bed should not exceed 500 m. (3) The human population should not be more than 1,000. (4) The wastewater treatment infrastructure was inadequate or problematic. (5) There was an open area next to the settlement for the constructed wetland. (6) There was a suitable site available for the CW. Considering the geographical and natural conditions and all these criteria, Ilyinskoye Village was selected as the model settlement. It is

Krasnogorsk City (west of Moscow), on the left bank of the Moskva River.

The exact location or point of the wastewater treatment plant was also identified using several criteria. (1) The land should be an open space with no buildings or economic activities on it. (2) The terrain should be slightly sloping towards the river. (3) The site should be located at the lowest point of this terrain and close to the settlement. (4) The site’s hydrological regime should not be regularly flooded. Accordingly, the constructed wetland should be built at the coordinates 55.7582717 N, 37.2377371 E, and the elevation 136 masl as seen in Figure 2.

located in the southern part of

Figure 2. The location of the Ilyinskoye Village relative to the Moscow megapolis and the Moskva River

Climate: The region has a moderate continental climate (characterized by moderately cold winters and moderately warm summers), generally identical to Moscow’s climate. The long-term average of atmospheric precipitation is 598 mm, peaking in summer. The highest and lowest temperatures are +26°C (June) and -9.8°C (January), respectively. The average annual air temperature is 4.5°C, and the average wind speed is 2.4 m/s.

Soils: Albeluvisols and fluvisols are common in the district. The frost depth is up to 1.5 m.

Landscape: The district’s morphology is part of the Smolensk-Moscow moraine-erosion upland, which is a ridge-hilly, weakly dissected hilly-undulating plain, sometimes hollow-hilly with low elevations. It is characterized by a network of erosion scars. The district lies in a landscape with average karst development and landslide processes.

To assess the water supply and sanitation in the villages, publicly available documents related to Ilyinskoye and other nearby villages were examined. Then, local authorities and residents were contacted to obtain official, accurate, and up-to-date information. This stage of

research turned out to be essential for clarifying the data previously collected from the literature. QGIS and Google Earth programs were used for the spatial analysis, and Microsoft Excel for the data analysis.

Design of the constructed wetlands

To design the constructed wetlands, relevant data were collected using these steps. (1) The landscape of the region and its surroundings was studied to meet the criteria for the constructed wetland placement. In doing so, topographic and cadastral maps were used. Subsequently, a field study of the selected site was conducted to ensure the consistency and reliability of the cartographic data. (2) The municipal authorities were contacted; then, the data from the Federal State Statistics Service were analyzed to determine the number of water users. (3) To determine the parameters of the wastewater inflow, data on urban wastewater treatment plants were recalculated for small settlements according to a decrease in their water consumption.

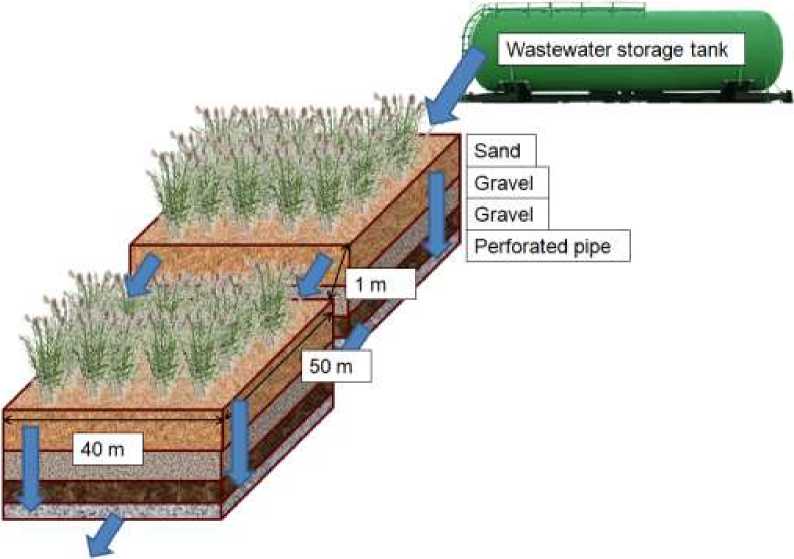

The technological assessments in this research were based on constructed wetlands with a French vertical-flow two-

stage system. The guidelines written by Davis (1995) and the manual book by UNHABITAT (2008) were consulted for the design.

Horizontal filters do not treat raw water but sludge or water pre-treated with vertical filters. Horizontal flow retains pollutants by prolonging their settling time in the system (UN-HABITAT, 2008)

Removal of nutrients (especially nitrogen) inside a constructed wetland is restricted due to limited oxygen transfer; nevertheless, this system washes out nitrates from wastewater. However, in this study, the nitrogen was assumed to be in low concentration.

A vertical flow system (VFS) uses a discontinuous flow, creating aerobic and anaerobic conditions alternately—which makes a vertical flow constructed wetland more effective than its horizontal flow counterpart. VFS has a stronger ability to transfer oxygen, guaranteeing effective nitrification. Also, VFS only requires a relatively small area to decrease COD, BOD5, and the population of pathogenic microorganisms. Unlike HFS, it removes phosphorus and nitrogen effectively (Li et al., 2008). International studies have found that the French vertical-flow two-stage system can be used to treat wastewater, considering the two-stage

efficiency is continuously maintained

(Torrens et al., 2021).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Hydrological characteristics of The Moskva River

The Moskva River has an average annual flow of 4.734 km3/year and an average annual discharge of 150.0 m3/s. The river is fed mainly by snow— accounting for 61% of the total inflow water, groundwater (27%), and rainwater (12%).

The Moskva River has been receiving water from the Volga River through the Moscow Canal since 1937, and an additional transfer of the Volga waters along the Vauze and Ruza Rivers has been organized since 1978, multiplying the natural river discharge by more than double. In addition, there are two complex hydroelectric complexes within the city and five more low-pressure hydroelectric complexes downstream. Thus, the Moskva River is a regulated watercourse with an anthropogenically altered hydrological regime.

Ecological characteristics of The Moskva River

The animal world of Moskva River is mainly represented by mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and insects typical of the Moscow region.

Still, the species composition is not constant and is periodically replenished due to anthropogenic factors. The ichthyofauna of the Moscow region includes about 40 species of Osteichthyes and one species of Cyclostomata, belonging to 17 families and 13 orders. Up to 123 species of planktonic algae: 64 species of diatoms, 52 species of planktonic green algae, eight species of Pyrrophyta, six species of blue-green algae, five species of golden algae, and five species of Euglena.

The presence of pollutants that are several times higher than their respective maximum permissible concentrations (MPCs) in water undoubtedly affects living organisms in a negative way. This includes competition between microorganisms where pathogenic bacteria inhibit the growth of water quality-indicator microbes.

Sources of pollution and anthropogenic pollutant load of The Moskva River

Along the entire length of the Moskva River, it is possible to distinguish between point and non-point (diffuse) sources of pollution. The primary point source of pollution is industry. More than 2000 enterprises in the Moscow region; (1,376 of which are in the City of Moscow) extract water from the river.

Industrial enterprises withdraw and discharge the second-largest water after housing and communal services enterprises. The Moskva River basin mainly generates pollutants containing nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, organic substances (including phenols, surfactants, petroleum products, etc.), and metal salts. All domestic and industrial wastewater entering the municipal sewerage system undergoes a full cycle of treatment at the Kuryanovo, Lyubertsy, Yuzhnoyebutovo, and Zelenograd plants. This, however, excludes the discharge of untreated wastewater from natural reservoirs.

In addition to point sources of pollution from the industries, there is a non-point (diffuse) source of pollution, namely surface runoff. It is one of the primary sources of pollution since almost the entire volume of runoff in the city drains into the river without prior treatment. During winter, snow makes a significant contribution because it contains dust, debris, anti-icing mixtures, and products of road surface destruction (i.e., petroleum products). Meanwhile, agriculture has the most influence during summer due to the application of pesticides, surfactants, heavy metals (Zn,

Cu, Fe, etc.), and petroleum products (agricultural machinery).

Based on the visual of the catchment areas obtained from satellite images, various land use/land cover as non-point sources of pollution were identified. Results showed that agricultural production accounts for 60% of the total diffuse sources, 30% from urbanized territories, transportation, and leaks from treatment facilities (particularly Kuryanovo and Lyubertsy treatment plants), and 10% from uncontrolled surface leaks of industrial production and landfills within the city. Water quality parameter values and legal standards

The natural water/wastewater ratio is 1:2, meaning the latter is twice as much as the former. Consequently, the water quality in the city and beyond is categorized as low. Exposure to the city’s anthropogenic loads and its effects on river water quality was assessed with pH, suspended solids, ammonium, BOD5, and phosphorus.

pH does not directly measure pollutant contents but is very indicative of changes in physical and chemical processes in a water body. Normally, the river pH is in the range of 6.8–7.6, but the Moskva River water is within the slightly alkaline interval, believed to result from

the disposal of detergents and other domestic and industrial byproducts into the river.

In the upper reach, the total suspended solid is 20.88 mg/l, far exceeding its maximum permissible concentration (MPC), 0.75 mg/l. The ammonium level is 0.07 mg/l in the upper reach, 0.25–1 mg/l in the middle, and 1.5– 2.5 mg/l in the lower reach. Thus, except for some points in the lower reach, the river’s ammonium content does not exceed its MPC, 2.0 mg/l. BOD5 in the upper reach is about 2.11 mg/l or below its legal MPC, 4 mg/l. Similarly, the phosphate level in the upper reach is 0.09 mg/l or below its MPC, 3.5 mg/l.

Constructed wetland design

-

1. Flow rate and approximate wastewater quality

To determine the technical specifics of the constructed wetlands with a French vertical-flow two-stage system, it is necessary to quantify the pollutant concentration for the model facility in Ilyinskoye. Every resident is assumed to generate an average of 150 liters of wastewater per person per day or approximately 75 m3 per day for the entire settlement (with a population of 500). These pieces of information were obtained by analyzing the flow indicators

in other settlements that share similar building development profiles and population conditions with Ilyinskoye.

Afterward, the pollutant concentration in wastewater was calculated based on the parameters used in the design of the Russian sewage treatment constructions for a capacity of 300 l/person/day. The parameter values were extrapolated to fit the treatment wetland capacity designed in this study,

150 l/person/day as listed in Table 2, using the Equation (1).

£, _ mpollutant × 1000 (1)

Qwastewater

where C denotes pollutant concentration in wastewater (mg/l), mpollutant is pollutant amount per person (g/day), and qwastewater is wastewater volume per person (l/day).

Table 2. Estimated parameter values of the domestic wastewater fed into the treatment plant

|

Parameter* |

Pollutant amount per person (g/day) |

Pollutant level in wastewater (mg/l) |

|

TSS |

65 |

433 |

|

BOD5 of an unlit liquid |

60 |

400 |

|

TN |

13 |

87 |

|

Nitrogen of ammonium salts |

10.5 |

70 |

|

TP |

2.5 |

17 |

|

Phosphorus of phosphates |

1.5 |

10 |

Notes: *from SP No. 32.13330.2018 on Sewerage, Pipelines, and Wastewater Treatment Plants, amended by N 1, on December 25, 2018; Information and technical guide to the best available technologies. (2019). p. 282

-

2. Constructed wetland dimension based on treated wastewater quality standards

To determine the treatment wetland area, the output quality should be first identified. This research referred to

the Russian regulations, as presented in Table 3. This table shows six water quality parameters (TSS, BOD5, NO2, NO3, NH4+, phosphates) and their respective MPCs.

Table 3. MPC values of some indicators according to Russian standards

|

Parameters |

MPC, mg/l |

|

TSS |

2.75 mg/L |

|

BOD5 |

3 mg O2/L |

|

NО2 |

3.3 mg N/L |

|

NO3 |

45 mg N/L |

|

NH4+ |

2 mg/L |

|

Phosphates |

1.2 mg P/L |

Furthermore, the treatment wetland size was calculated using the formula proposed by Kikut in Equation (2).

_ Qd(lnCi - InCe) (2)

^h = v

kBOD

where Ah is bed surface area (m2), Qd is average daily wastewater use (m3/day; population x specific wastewater use : 1000), Ci is inflow’s BOD5 concentration (mg/l), and Ce is BOD5 concentration in treated wastewater (mg/l). КBOD is constant speed (m/day), which is defined in Equation (3) and Equation (4)

Kbod = K×T×d×n (3)

with K,

K = K20(1.06)cr-20) (4)

where K20 is constant speed at 20 ºC (d-1), T is the system’s operating temperature (ºC), d is water column depth (m), and n is

the substrate medium’s porosity (%, expressed in fractions).

Results showed that KBOD was 0.2 m/day for the VF constructed wetland operated at 20°C with a substrate depth of 70 cm and 30% porosity. The average daily wastewater use (Qd) was 75 m3/day (population of 500 x 150 l/day/person : 1000). The area required to reduce 400 mg/l BOD5 in the influent flow to 2 mg/l in the system effluent was 1,986.9 m2 (specific area: 3.94 m2 per person).

To minimize energy costs, the CW should be located at a lower elevation than the settlement but above the discharge area and with a minimum allowable distance to the settlement and the river. Also, it should not be at the lowest point of the terrain to avoid flooding.

As per these criteria, it was decided to build the treatment plant

southeast of the Ilyinskoye settlement on the northern upper terrace (upper floodplain) of the Moskva River as seen in Figure 3. At the same time, the dead arm of the river has the lowest elevation.

Moreover, according to the soil map of the Moscow region, this area has alluvial soils. Therefore, the CW will require a seal (liner) with plastic.

Figure 3. The village of Ilyinskoye (pink-colored) and the recommended position for the

constructed wetlands (yellow box).

Based on the calculation results, the required wetland area is 1986.9 m2 or rounded up to 2000 m2. Thus, the two reservoirs should each have a surface area of 40x50 m2 (two reservoirs: two-stage cleaning). The minimum distance to the settlement is 15–20 m, and the distance

between the reservoirs is at least 1 m. Also, for two-stage processing, the height difference between the two tanks should be 1 m. Since the terrain does not allow such a difference, the existing slope should be terraced as shown in Figure 4.

-

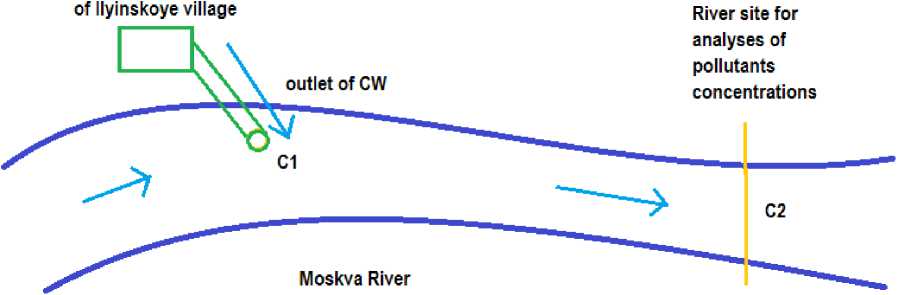

4. Potential water quality

improvement after treatment with constructed wetlands

Treatment plants remove nutrients and other pollutants from wastewater. Accordingly, these pollutants will not be disposed of into the Moskva River and/or onto the landscape. Available databases

eISSN: 2655-9994 pISSN: 2303-3371 https://doi.org/10.24843/IJBBSE.2023.v01.i01.p06

on water quality and water discharge at the Rublevo section were consulted to assess the potential change in the river water quality after wastewater treatment as shown in Figure 5. In this process, the number of pollutants removed from wastewater was also calculated in Table 4.

Figure 4. Schematic of the designed vertical flow constructed wetlands

The parameters observed were TSS, BOD5, TN (total nitrogen), NH4+, TP (total phosphorus), and phosphates. Based on the results, the CW makes a small but important contribution to improving the

water quality in the Moskva River. The greatest changes were seen in ammonium salts (a 0.5% decrease), BOD5 (0.266%), and total nitrogen (0.138%).

Constructed wetlands

Figure 5. Schematic of the river section Rublevo relative to the constructed wetlands.

Table 4. Сalculation of pollutants removed from wastewater for the Rublevo section

|

Parameter |

Pollutant Concentration |

Pollutant Amount |

Estimated post-treat conc. RS* (mg/l) | |||||

|

RS (mg/l) |

Inlet (mg/l) |

Outlet (mg/l) |

I/O Diff. (mg/l) |

RS (mg/day) |

Removed* (mg/day) |

%Removal (mg/day) | ||

|

TSS |

20.88 |

434 |

20.0 |

414.0 |

104,626,640.0 |

31,050.0 |

0.030% |

20.87 |

|

BOD5 |

2.11 |

400 |

25.0 |

375.0 |

10,572,902.8 |

28,125.0 |

0.266% |

2.10 |

|

TN |

1.71 |

86 |

2 |

84.0 |

8,568,561.0 |

6,300.0 |

0.074% |

1.71 |

|

NH4+ |

0.07 |

70 |

45.0 |

25.0 |

350,759.8 |

1,875.0 |

0.535% |

0.07 |

|

TP |

0.16 |

16 |

1.2 |

14.8 |

801,736.7 |

1,110.0 |

0.138% |

0.16 |

|

Phosphorus (of PO43-) |

0.09 |

10 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

450,976.9 |

375.0 |

0.083% |

0.09 |

Notes: RS: Rublevo section; I/O Diff.: Difference between inlet and outlet concentrations;

*calculated for 500 people

Afterward, the same calculations were made for the entire population of the small settlements in the ‘Upstream Moscow’ section, which are no further than 500 m from the Moskva River and have inadequate sewage treatment systems. This area has a population of 25,000.

Suppose a CW is built for all these people and the pollutant concentration is consequently decreasing. Then, the amount of pollutant removed will be as calculated below:

_ (D0ld - D') (4)

^new

Hriver

where Cnew is the concentration of substance passing through the Rublevo section after the CW is operated, Dold is the current amount of substance passing through the Rublevo section, D’ is the amount of substance removed from wastewater, and qriver is the water discharge of the Rublevo section (5,010,854.4 m3/day).

eISSN: 2655-9994 pISSN: 2303-3371 https://doi.org/10.24843/IJBBSE.2023.v01.i01.p06

Table 5 shows the calculation results for TSS, BOD5, TN, NH4+, and TP. Estimated post-treatment concentrations indicated that the BOD5, NH4+, and TP levels in the Rusblova section would be below their respective maximum permitted concentrations (MPCs) or be restored to natural presence. These results are assumed to be achieved with a vertical flow constructed wetland designed for a small number of people (i.e., 25,000).

Table 5. Current and estimated parameter values after the constructed wetland installation

|

Parameter |

Current conc. Estimated post-treat conc. (mg/l) (mg/l) |

|

TSS BOD5 TN NH4+ TP |

20.88 5.93 2.11 below MPC 1.71 0.21 0.07 below MPC 0.16 below MPC |

CONCLUSIONS

A solution for the untreated wastewater problem has been proposed for small settlements in the Moskva River basin. The village of Ilyinskoye in the river’s upper course has been selected as a model settlement. Based on the area’s geographical and social-economic conditions, the nature-based French system is deemed the most suitable constructed wetland. For the Ilyinskoye

settlement, the treatment wetland should have a specific area of 3.94 m2per person.

CW is expected to contribute to improving the water quality of the Moskva River by decreasing the pollutant concentrations, as calculated for the Rublevo section downstream of the settlement. It is also expected that installing several systems near different segments of the Moskva River will significantly improve its ecological state.

Introducing this technology to the Moscow region will be far from complicated due to the availability of suitable infrastructure, transport accessibility, territories available for its construction, and natural conditions (relief, vegetation, hydrological regime, etc.). On the one hand, the constructed wetland is considered suitable for the region, especially with more population having little to no access to modern treatment facilities in the coming years. On the other hand, its implementation demands (1) the development of laws regulating its construction and application and (2) human resources experience in adapting or adjusting it to low temperatures, making the stages of its introduction more complicated. Furthermore, the results of this project can be straightforwardly upscaled to estimate the applicability of constructed wetlands to the entire region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to Dr. Natalia Shchegolkova from Lomonosov Moscow State University for providing access to databases and consultations during the research project. Gratitude is also extended to the Agroecouniversum club and its affiliated team of experts for

aiding in the research organization and related consultations.

REFERENCES

Озерова, Н. А. (2014). Москва-река в пространстве и времени.

Прогресс-Традиция.

Правительство Москвы, Департамент природопользования и охраны окружающей среды (2019), «О состоянии окружающей среды в городе Москве в 2018 году», Студио Арроу, Москва.

Яшин Иван Михайлович, Васенев Иван Иванович, Гареева Ирина Викторовна, & Черников

Владимир Александрович (2015). Экологический мониторинг вод Москвы-реки в столичном мегаполисе. Известия

Тимирязевской сельскохозяйственной академии, (5), 8-25.

Brion, N., Verbanck, M. A., Bauwens, W., Elskens, M., Chen, M., & Servais, P. (2015). Assessing the impacts of wastewater treatment

implementation on the water quality of a small urban river over the past 40 years. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(16), 12720-12736.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4493-8

Coulter, A. A., Brey, M. K., Lubejko, M., Kallis, J. L., Coulter, D. P., Glover, D. C., ... & Garvey, J. E. (2018). Multistate models of bigheaded carps in the Illinois River reveal spatial dynamics of invasive species. Biological Invasions, 20(11), 3255-3270.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1772-6

Davis, L. (1995). A handbook of constructed wetlands: A guide to creating wetlands for: agricultural wastewater, domestic wastewater, coal mine drainage, stormwater. In the Mid-Atlantic Region. Volume 1: General considerations. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service.

De Ceballos, B. S. O., Oliveira, H., Meira, C. M. B. S., Konig, A., Guimaraes, A. O., & De Souza, J. T. (2001). River water quality improvement by natural and constructed wetland systems in the tropical semi-arid region of Northeastern Brazil. Water science and technology, 44(11-12), 599-605.

https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2001.08 86

Eremina, N., Paschke, A., Mazlova, E. A., & Schüürmann, G. (2016). Distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls, phthalic acid esters, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and organochlorine substances in the Moscow River, Russia. Environmental Pollution, 210, 409418.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.20 15.11.034

Jechow, A., & Hölker, F. (2019). How dark is a river? Artificial light at night in aquatic systems and the need for comprehensive night‐time light measurements. Wiley

Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 6(6), e1388.

https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1388

Jin, Z., Zhang, X., Li, J., Yang, F., Kong, D., Wei, R., Huang, K., Zhou, B. (2017). Impact of wastewater treatment plant effluent on an urban

river. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 32(1), 697-710.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2 017.1394917

Jing, S. R., Lin, Y. F., Lee, D. Y., & Wang, T. W. (2001). Nutrient removal from polluted river water by using constructed wetlands. Bioresource Technology, 76(2), 131-135.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00100-0

Kadlec, R. H., & Hey, D. L. (1994). Constructed wetlands for river water quality improvement. Water Science and Technology, 29(4), 159-168.

https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.1994.01 81

Kennedy, G., & Mayer, T. (2002). Natural and constructed wetlands in Canada: An overview. Water

Quality Research Journal, 37(2), 295-325.

https://doi.org/10.2166/wqrj.2002.0 20

Kraft, M. E. (2006). Sustainability and water quality: Policy evolution in Wisconsin’s Fox-Wolf River basin. Public Works Management & Policy, 10(3), 202-213.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X0 6287498

Lawton, H.W., Wilke, P.J. (1979). Ancient Agricultural Systems in Dry Regions. In: Hall, A.E.,

Cannell, G.H., Lawton, H.W. (eds) Agriculture in Semi-Arid

Environments. Ecological Studies, vol 34. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-67328-3_1

Li, L., Li, Y., Biswas, D. K., Nian, Y., & Jiang, G. (2008). Potential of constructed wetlands in treating the

eutrophic water: evidence from Taihu Lake of China. Bioresource technology, 99(6), 1656-1663.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2 007.04.001

Mackay, D. (1945). Ancient river beds and dead cities. Antiquity, 19(75), 135-144.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X 00022675

Martínez-Santos, M., Lanzén, A., Unda-Calvo, J., Martín, I., Garbisu, C., & Ruiz-Romera, E. (2018). Treated and untreated wastewater effluents alter river sediment bacterial communities involved in nitrogen and sulphur cycling. Science of the Total Environment, 633, 1051

1061.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2 018.03.229

McGrane, S. J. (2016). Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: a review. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 61(13), 2295-

2311.https://doi.org/10.1080/02626 667.2015.1128084

Miara, A., Vörösmarty, C. J., Macknick, J. E., Tidwell, V. C., Fekete, B., Corsi, F., & Newmark, R. (2018). Thermal pollution impacts on rivers and power supply in the Mississippi River watershed. Environmental Research Letters, 13(3), 034033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaac85

Notteboom, T., Yang, D., & Xu, H.

(2020). Container barge network development in inland rivers: A comparison between the Yangtze River and the Rhine River. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 132, 587-605.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.1 0.014

Pokhrel, Y., Burbano, M., Roush, J., Kang, H., Sridhar, V., & Hyndman, D. W. (2018). A review of the integrated effects of changing climate, land use, and dams on Mekong River hydrology. Water, 10(3), 266.

https://doi.org/10.3390/w10030266

Razali, A., Syed Ismail, S. N., Awang, S., Praveena, S. M., & Zainal Abidin, E. (2018). Land use change in highland area and its impact on river water quality: a review of case studies in Malaysia. Ecological processes, 7(1), 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0126-8

Shchegolkova, N., Shmonin, K., Emelyanov, A., Kozlova, M. (2018). The Moskva River Today and Tomorrow. Priroda, (10), 2837.

https://doi.org/10.31857/S0032874 X0001449-2

Sheng-Bing, H. E., Li, Y., Hai-Nan, K. O. N. G., Zhi-Ming, L. I. U., De-Yi, W. U., & Zhan-Bo, H. U. (2007).

Treatment efficiencies of

constructed wetlands for eutrophic landscape river water. Pedosphere, 17(4), 522-528.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(07)60062-9

Torrens, A., Folch, M., & Salgot, M. (2021). Design and performance of an innovative hybrid constructed wetland for sustainable Pig slurry treatment in small farms. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 8, 577186.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020. 577186

Tu, Y. T., Chiang, P. C., Yang, J., Chen, S. H., & Kao, C. M. (2014).

Application of a constructed wetland system for polluted stream remediation. Journal of hydrology, 510, 70-78.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.20 13.12.015

UN-HABITAT, Constructed Wetlands Manual. (2008). UN-HABITAT Water for Asian Cities Programme Nepal.

Wang, Q., Liang, J., Zhao, C., Bai, Y., Liu, R., Liu, H., & Qu, J. (2020). Wastewater treatment plant upgrade induces the receiving river retaining bioavailable nitrogen sources. Environmental Pollution, 263, 114478.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.20 20.114478

Yustiani, Y. M., Nurkanti, M., Suliasih, N., & Novantri, A. (2018).

Influencing parameter of selfpurification process in the urban area of Cikapundung River, Indonesia. GEOMATE Journal, 14(43), 50-54.

https://doi.org/10.21660/2018.43.3 546

Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Shi, P., Bi, Z., Shan,

Z., & Ren, L. (2021). The deep challenge of nitrate pollution in river water of China. Science of the Total Environment, 770, 144674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv. 2020.144674

78

Discussion and feedback