Resident Perception of Conflict with Tourism Enterprise: An Investigation at A Mountainous Destination in Vietnam

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.9. No.2. (2022): 126-143

Resident Perception of Conflict with Tourism Enterprise: An Investigation at A Mountainous Destination in Vietnam

Duong Thi Hien1*, Tran Duc Thanh2

-

1 Hong Duc University, Vietnam

-

2 University of Social Science and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam

*Corresponding Author: duongthihien@hdu.edu.vn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24922/eot.v9i2.92113

Article Info

Submitted:

June 14th 2022

Accepted:

September 15th 2022

Published:

September 30th 2022

Abstract

Based on extended social exchange theory, the authors propose a framework to investigate the conflict of local residents with tourism businesses. The authors applied a random sampling method and approached 388 residents living in Pu Luong Nature Reserve, a renowned community based tourism destination in Thanh Hoa mountainous area, Vietnam. The findings show that resident’s conflict with tourism business is influenced by latent variables: community’s involvement, perceived benefit and perceived cost. This study is an additional contribution to the theoretical perspective of tourism conflict. In addition, some practical implications are made for local authorities to promote sustainable tourism.

Keywords: Conflict; mountainous destination; resident; stakeholder relationship; tourism enterprise.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Tourism is an essential tool for economic development. It is a power catalyst to alter many regions to become flourishing lands in the world. The tangible economic benefit gained from tourism industry has appealed to all authorities and stimulated them to give priority on the development of this sector. To promote tourism, there should be the cooperation and consensus of all stakeholders including government, resident, tourist, tourism enterprise, destination development organization, etc. Among them, residents' support is a key component for sustainable development goals; especially at community based tourism destinations where the local http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

community is considered as the center of all tourism activities and orientation (Sebele, 2010; Tosun, 2006). They are mentioned as the owners, operators, managers and beneficiaries of tourism activities (Goodwin & Santilli, 2009).

In many remote areas, despite the plentiful tourism resources; the industry of tourism is hindered by unfavorable conditions, such as underdeveloped infrastructure, limited education capacity or lack of finance. In those cases, local authorities tend to call for investment from both locals and outsiders. The support of these units may help locations to upgrade tourism infrastructure, connect markets and bring tourists to location, build more entertainment facilities and provide necessary training for the local community (Goodwin &

Santilli, 2009). Nevertheless, the dark sides caused by tourism enterprises have been criticized at some destinations. They are biased policies, unfair benefit distribution, environmental pollution and traditional deterioration. Tourism businesses have been criticized for the loss of local cultural value and the reduction of community cohesion, unfair benefit distribution, environmental pollution and natural landscape deterioration. Those negative impacts have withdrawn resident support and led to hostile behaviors. Residents marched and protested tourism business (Jinsheng & Siri-phon, 2019), burnt tourists' coach, vandalized tourist boats (Ebrahimi & Khalifah, 2014), closed village gate to protest tourist to enter (Wang & Yotsumoto, 2019). Those unfriendly actions not only worsen the destination image but also disrupt the development of tourism industry. They prevented resource integration, wasted resources, damaged tourism management attempts and negatively affected related benefits (Apostolidis & Brown, 2021; Canavan, 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Prior & Marcos-Cuevas, 2016; Yang et al., 2013); thereby, created barriers to tourism projects at community (Lo & Janta, 2020; Tesfaye, 2017; Wang, 2021).

Thus, one of the important issues to maintain and ensure the sustainability of a tourist destination is to identify the conflicts arisen between the local community and tourism businesses; clarify the antecedents of conflicts and then promote a conflict management model. Effective conflict management strategies are essential to avoid devaluation, encourage cooperation and resource integration, which may support the destination to achieve Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations for tourism (Apostolidis & Brown, 2021). This study will investigate the conflict of local residents with tourism businesses at Pu Luong Nature Reserve, an emerging community based tourism destination in Thanh Hoa mountainous area, http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

Vietnam. The finding is an additional contribution to the theoretical perspective of tourism conflict. It also offers valuable insights to policy-makers to propose strategic actions to avoid conflict and promote sustainable tourism.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Residents - tourism enterprises conflict

The conflict between residents and tourism businesses has been mentioned in many studies. These two groups often dispute over some main issues: the ownership and access to public resources, unfair benefit distribution, polluted environment and traditional deterioration. Tourism businesses have been criticized for cooperating with authorities to take over and control important resources (especially land resources) (Engström & Boluk, 2012; Glasson, et al., 1995; Lo & Janta, 2020; Wang & Yotsumoto, 2019; Xu et al., 2017; Xue & Kerstetter, 2018; Yang et al., 2013). Glasson et al. (1995) reported that the dominance of the industry by non-local investors can reduce residents’ control over local resources. Engström & Boluk (2012) also revealed that the most prominent conflict between resident and tourism company during the planning process was the unfair power relationship, the residents could not raise their voice while tourism business, accompanied by local government, gained most of the advantages in the use of local resources.

Xue & Kerstetter (2018) confirmed that these two parties share the same development goal, but they have contradictions in values, attitudes and theory. The authors noted that residents are frustrated with tourism businesses because the investor cooperated with the government to abuse power and take over most of local resources. Similarly, Lo & Janta (2020) asserted that community-based tourism brings local residents opportunities to

promote economic development by utilizing community’s natural as well as cultural resources; however, when tourism is developed, it may create conflicts between residents and investors over resource ownership. Residents reflected that their important lands had fallen into the hands of outside developers.

Many residents complained that tourism benefits mainly belong to the business while the residents receive little or get no economic benefit at all (Jinsheng & Sir-iphon, 2019; Lo & Janta, 2020; Bussaba Sitikarn, 2008). According to Jinsheng & Siriphon (2019), local residents believed that they - as the true owners of the community's tourism resources, who play an important role in tourism projects - should receive a larger distribution of tourism income. Meanwhile, the investors insisted that the revenue from tourist tickets should be retained for the company. They explained that the tourism companies must be responsible for many important actions such as scenic management and marketing promotion, renovating destination landscape, constructing and maintaining infrastructure, paying taxes to the government; therefore, the profit must be theirs. With different points of view, these two groups had come to conflicting actions. Residents gathered around the business gate area to protest and boycott tourism businesses. Si-tikarn (2008) also mentioned that more than 70% of revenue belongs to private entrepreneurs, which leads to frustration in community.

Tourism businesses are also criticized for environmental pollution (Ebrahimi & Khalifah, 2014; Gascón, 2012; Jinsheng & Siriphon, 2019; Mannon & Glass-Coffin, 2019) and deteriorate natural landscape (Kreiner, Shmueli, & Gal, 2015). According to Ebrahimi & Khalifah (2014), non-participants often have a jealous attitude towards the neighbors who run businesses and take advantage of community’s resources to get individual economic

benefits. Moreover, problems of noise, air pollution, water pollution, resource degradation, etc., make non-participants feel more annoyed and criticize the tourism businesses. Kreiner et al. (2015) revealed that residents felt threatened when there was interference in the construction process which disturbed and messed up natural landscape. In addition, enterprises’ infringement may threaten local religious, cultural and social values. The differences in cultural values and social norms led to conflict between the two parties and even provoked negative behaviors afterward. Other studies also affirmed that the business of tourism enterprises causes the loss of local cultural value and the reduction of community cohesion (Kinseng et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2017; Xue & Kerstetter, 2018).

Conflict antecedents

According to SET, social interactions are essentially an exchange process, each individual will assess what they gain and lose. They will join in a relationship and do something when they receive benefits, if the cost outweighs the benefits, they tend to terminate or leave the relationship (Homans, 1961). In tourism, SET has been used by many scholars to analyze the attitudes and behaviors of related groups (such as: Andereck et al., 2005; Chen, 2018; Choi & Sirakaya, 2005; Gan, 2020; Ju-rowski & Gursoy, 2004; Ko & Stewart, 2002; Nunkoo et al., 2016; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Sharpley, 2014). Those studies suggested that when local people realize the perceived benefits are less than the cost, they may have anti attitudes and behaviors toward tourism development as well as specific groups who are promoting tourism development in their locality.

Sitikarn (2008), Timur & Getz (2008), McCool (2009) and Mannon & Glass-Coffin, (2019) have also confirmed that the downsides of tourism are important reasons for the conflicts at destinations. McCool (2009) mentioned that the conflict e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

arises when local people realize that tourism development causes negative effects on their living environment, change cultural values. Inappropriate use or loss of resources is also an important cause of dispute and conflict in the tourism industry (Liu et al., 2017; Tao & Wall, 2009; Zhang et al., 2015). In other words, residents' perceptions may influence conflicts between residents and stakeholders. Therefore, following research hypotheses were presented:

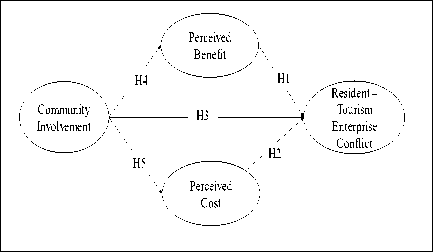

H1: Perceived benefits directly and negatively affects residents - tourism enterprise conflict.

H2: Perceived cost directly and positively affects residents - tourism enterprise conflict.

According to Lee (2013) and Nugroho & Numata (2020), the original SET do not examine the mechanism on how resident perceives costs and benefits of tourism development in particular social circumstances. Therefore, they proposed an additional framework, extended SET, to clarify the mechanism of locals’ attitude and behavior. They found that residents' perceived cost and benefit may be influenced by other factors. An important one which has been mentioned in numerous studies is community involvement (Choi & Sirakaya, 2005; Jurowski & Gursoy, 2004; Nicholas et al., 2009; Nunkoo et al., 2016; Presenza et al., 2013; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015; Sekhar, 2003; Sirivongs & Tsuchiya, 2012).

These scholars all implied that community involvement closely relates to resident’s perceived benefit, perceived cost as well as resident’s atitude. If the residents are involved in tourism, they have more chances to be beneficial from tourism (Sebele, 2010). Also, if residents participated in natural management, they have chance to understand and aware of natural protection. The involvement in management and decision-making may create incentives for residents to integrate tourism http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

into the local economy (Aas et al., 2005; Simmons, 1994). A recent study by Nugroho & Numata (2020) also revealed that the more the community members are involved in tourism, the more they support tourism development. Butler (1980), Prosser (1994) and Ceballos-Lascurain (1996) have noted that resentment, antagonism, and alienation often arise between locals and tourism investors if the locals are not involved in the tourism business. To resolve conflicts, maximizing resident participation is a solution proposed by many researchers (Bhalla et al., 2016; Connor & Gyan, 2020; Curcija et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2019). Accordingly, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H3. Community involvement directly and negatively associated with residents -tourism enterprise conflict.

H4. Community involvement indirectly and negatively associated with residents - tourism enterprise conflict through perceived benefit.

H5. Community involvement indirectly and positively associated with residents - tourism enterprise conflict through perceived cost.

Figure 1. Research framework

RESEARCH METHODS

Study Site

Pu Luong Nature Reserve belongs to 2 mountainous districts of Thanh Hoa province (Ba Thuoc and Quan Hoa), about170 km from Hanoi and 130 km from Thanh Hoa city. This place has favorable

conditions for tourism development: unspoiled nature, picturesque landscape, fresh atmosphere, unique and rustic lifestyle of ethnic minorities. With those potentials, Pu Luong Nature Reserve has attracted thousands of tourists since the early 2000s. To boost tourism economy, the local government has proposed various policies to attract investors to modernize infrastructure and promote destination. Realizing the investment opportunities, along with the welcome of local government, many investors (both domestic and foreign ones) have come to start up business at locality. They buy potential area or rent local houses to build homestay resorts. So far, there have been hundreds of tourism enterprises at Pu Luong nature reserve. Among them, dozens of accommodation establishments are owned by external investors.

Research process

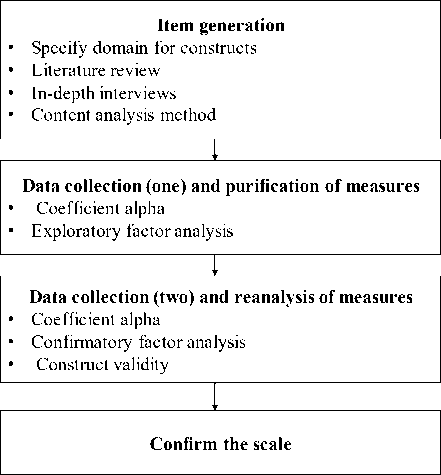

The research process was divided into two phases. Firstly, a qualitative study was carried out to synthesize and adjust the theoretical model. Beside literature review, the in-depth interviews were conducted to develop a scale used to measure related concepts, especially the concept of conflict between residents and tourism businesses. Quantitative research will be conducted in the next step. Residents who are living in selected areas will be interviewed and asked to complete a questionnaire with main content of community involvement, perceptions of benefit and cost, stakeholder conflicts. Age, sex, education level, occupation and ethnic are also asked for sorting purpose.

Measures

The concept of community involvement is based on the scale developed by Lee, (2013) and Nugroho & Numata (2020) including 4 components. The concept of perceived benefits and perceived costs are obtained from previous research

of Gursoy & Rutherford, (2004), consist of 18 variables (11 variables for measuring perceived benefits and 7 variables for measuring perceived costs).

With the concept of conflict between residents and tourism businesses, the authors develop and modify based on 4-steps research process proposed by Churchill (1979) and Wang et al., (2007): 1. Generate items, 2. Collect data and purify measures, 3. Collect data with other populations and reanalysis the measures, 4. Confirm the scale (Figure 2). As a result, a scale of six variables has been confirmed for empirical study.

Figure 2. Scale generation process

Step 1. Item generation

According to Churchill (1979), the first step in the procedure of scale development is to precisely specify the domain for constructs. The concept of conflict was defined by Thomas (1976, p.891) as “the process which begins when one party perceives that another has frustrated, or is about to frustrate, some concern of his”. Similarly, Wall & Callister (1995) stated: “Conflict is a process in which one party perceives that its interests are being opposed or negatively affected by another

party”. So, the feeling of disagreement, negative emotions, and interference are three aspects to specify the concept of conflict. Based on these three components, the author lists and arranges the conflicting contents mentioned in previous studies to create a variable pool. At the same time, these aspects are used to design interiew guide for in-depth interview with stakeholders. 14 residents, 4 enterprise managers and 4 local tourism management officials in Pu Luong Nature Reserve were purposely approached to reveal conflicting issues between residents and tourism business. MAXQDA software was used to analyze in-depth interview data afterward. All residents' expressions of disagreement, negative emotions, and interference with tourism enterprises were counted as a unit of analysis which were then coded and sorted into specific variables about conflict.

From literature review, there were 45 analysis units referring to the conflict between residents and tourism businesses, these units were sorted into 7 items. However, an item may be retained when at least 6 experts mentioned (Bearden et al., 1989, 2001). After screening, 2 components for the concept of conflict between residents and tourism businesses are retained. Five components were mentioned by less than 6 experts and were excluded from the list. With in-depth interview data, 80 analytical units referring to conflicts between residents and businesses were obtained, sorted into 9 components. Using the principle of Bearden et al., (1989, 2001), a component is retained when 6 or more respondents mentioned, 6 components for the concept of residents - tourism enterprises conflict between were retained. Actually, all of these items had been mentioned in previous studies (Table 1).

Table 1. Components of residents - tourism enterprise conflict from literature review and

in-depth interviews

|

Items |

Source (Literature review) |

In-depth interview (Frequency) |

|

Residents receive very little economic share from tourism enterprises |

(Feng & Li, 2020; Jinsheng & Siriphon, 2019; Lo & Janta, 2020; Bussaba Sitikarn, 2008) |

17 |

|

Tourism enterprises changes the traditional culture of local residents |

(Kinseng et al., 2018; Kreiner et al., 2015; McCool, 2009; Xue & Kerstetter, 2018) |

16 |

|

Tourism enterprises pollute local environment |

(Ceballos-Lascurain, 1996; Ebrahimi & Khalifah, 2014; Gascón, 2012; Glasson et al., 1995; Jins-heng & Siriphon, 2019; Mannon & Glass-Coffin, 2019; Prosser, 1994) |

9 |

|

The continuous construction of tourism enterprises disrupts the original landscape |

(Kreiner et al., 2015) |

9 |

|

External investors have controlled local tourism resources and activities |

(Glasson et al., 1995; Jinsheng & Siriphon, 2019; Kinseng et al., 2018; Lo & Janta, 2020; Wang & Yotsumoto, 2019; Xu et al., 2017; Xue & Kerstet-ter, 2018; Yang et al., 2013) |

8 |

|

Tourism business reduces cohesion in the community and change’s social structure in the community |

(Kinseng et al., 2018; Kreiner, et al., 2015; Xue & Kerstetter, 2018) |

8 |

After developing an item pool for the scales, 7 experts who are researchers and managers in tourism industry were asked to evaluate the content validity and revise the wording. They were asked to offer suggestion to add or delete inappropriate, ambiguous, and non-representative items (Hardesty & Bearden, 2004; Zaichkowsky, 1985). Every expert was asked to score items using a scale from 1 (extremely unsuitable) to 5 (extremely suitable). Any item that has a score lower than 3 would be deleted. As a result, 6 items were scored above 3 points and therefore were retained. Some components were adjusted in terms of words so that the meaning of the sentence become clearer and more coherent.

Step 2. Data collection and purification of measures

To verify the clarity, reliability and relevance of the scale, a pilot test was conducted with a small sample size. The questionnaire was distributed to 150 local people in September 2021. 148 valid questionnaires were collected and analyzed for reliability (Coefficient alpha) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The result showed that all factors have Cronbach's Alpha (CA) value greater than 0.6 and were thus considered to be reasonably reliable (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) and in conformance with the criteria for internal consistency (Hair et al., 2010). For the result of EFA, with varimax rotation, the Eigenvalues and variance were extracted to 5 (groups) of main factors with Eigenvalues > 1, the smallest Eigenvalues was 1.202. The cumulative percentage of explained variance was 68.347% > 50%. One item of perceived benefit and one item of perceived cost had factor loadings lower than 0.5 and were thus excluded. All items of community involvement and resident – tourism enterprise conflict had factor loading greater than 0.5 and then were retained (Hair et al., 2013). http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

Step 3. Data collection (two) and reanalysis of measures

Although the scales have been refined and verified to be reliable, Churchill (1979) suggested that the scales should be tested again with different samples. Therefore, a second pilot survey was conducted in November 2021. The data then was reanalyzed for CA, EFA, to ensure that the scale is valid and reliable. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was analysed to check whether the theoretical model is appropriate or not.

The sample size of the second pilot survey was 150. The results of analysis of CA, EFA, CFA of all scales were acceptable. Specifically, all scales had Cronbach's Alpha coefficient greater than 0.8. All variables had the total correlation coefficient greater than 0.3. The value of EFA showed that the KMO index was 0.866 > 0.5, the results of Barlett's test was 4376.816 with the Sig = 0.000 < 0.05; value of total variance extracted = 71.469% > 50%; the smallest Eigenvalues of factors was 1.824>1, and were accepted. The composite reliability of each construct was greater than 0.7, indicating high internal consistency. Moreover, the factor loading of each item was greater than 0.5; the AVE of constructs was from 0.675 to 0.697 > 0.5, indicating that the scale possessed favorable convergent validity (Hair et al., 2013). The square root of the AVE of each construct was higher than the correlation coefficient between any two constructs, demonstrating the discriminant validity of the scale (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All HTMT coefficients were lower than 0.9 (the highest is 0.482); thus, the scales in the structures are all discriminatory (Henseler et al., 2015).

Step 4. Confirm the scale for empirical study

The official scale for empirical study includes 22 items (4 items for community

involvement, 10 items for perceived benefits, 6 items for perceived cost, and 6 items for resident – tourism enterprise conflict (Table 2).

Sampling and survey procedures

According to Hair et al., (1998) the minimum sample is five for one variable. The total variable in the study is 22, so the minimum sample is 110. In the study, the authors randomly approached and collected 388 valid samples. Respondents must be 18 years old or above. Due to the low level of education in mountainous areas, many locals do not know how to use the internet and email, so the author used the face to face survey method to achieve the highest efficiency (Neuman, 2014). In addition, with direct survey, the investigator may explain for residents in case they have any question. A group of students majoring in Tourism at Hong Duc University, who are also locals, were trained to conduct the survey. Respondents were introduced to the purpose of the survey, and whether they agreed to take part in the survey or not. If they agree, the respondent may read the questionnaire on their own or the investigator can help. After completing the questionnaire, respondents were given a small gift. The survey was conducted in 2 months, from December 2021 to January 2022. SmartPLS 3.3.7 software was used to process and evaluate data. The research model was tested using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).

FINDINGS

Demographic information

Regarding gender, 64.9% of the respondents were male and 35.1% were female. 36.6% were aged between 18 and 24 (gen Z), 27.7% were aged between 24-40 (gen Y), 26% were aged 41-55 (gen X), the rest were above 55. There are 4.6% of respondents who did not attend any training school, 14.4% had completed primary school, 37.1% had completed secondary school, 36.9% had graduated from high school, 4.6% had qualified with vocational degree and 2.8% had bachelor degree. Most of the respondents have lived in the locality for more than 20 years.

Assessment of the measurement model

Table 2 shows the overall values of the latent variables in the questionnaire and they are all accepted. Regarding the overall reliability, Cronbach’s alpha values for community involvement (CI), perceived benefits (PB), perceived costs (PC), and resident - tourism enterprise conflict (REC) are 0.902, 0.935, 0.905 and 0.903, respectively. Composite Reliability (CR) are all greater than 0.9>0.8 (Daskalakis & Mantas, 2008). Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) coefficients of all factors were less than 5 and are accepted (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 2. Measurement properties

|

Construct/Items |

Factor Loading (>0.7) |

CA (>0.7) |

CR (>0.6) |

AVE (>0.5) |

VIF (<5) |

|

Community Involvement |

0.902 |

0.932 |

0.773 | ||

|

I participate in tourism-related activities |

0.861 |

0.749 |

2.444 | ||

|

I support research on tourism in the locality |

0.891 |

0.793 |

2.816 | ||

|

I am involved in the planning and management of tourism in this community |

0.886 |

0.792 |

2.924 | ||

|

I am involved in the decision-making for tourism development in this community |

0.880 |

0.791 |

2.830 | ||

|

Perceived Benefit |

0.910 |

0.925 |

0.552 | ||

|

Tourism increase employment opportunities |

0.761 |

0.676 |

2.017 | ||

|

Tourism increase investment opportunities |

0.758 |

0.671 |

4.364 | ||

|

Tourism provide more business for local people and small businesses |

0.758 |

0.674 |

4.062 | ||

|

Tourism provide incentive for the preservation of local culture |

0.711 |

0.626 |

1.968 | ||

|

Tourism provide more parks and other recreational areas for locals |

0.722 |

0.650 |

2.136 | ||

|

Tourism provide an incentive for the restoration of historical buildings |

0.758 |

0.707 |

3.931 | ||

|

Tourism improve the standards of road and other public facilities |

0.747 |

0.697 |

3.851 | ||

|

Tourism develop cultural activities by local residents |

0.737 |

0.677 |

2.004 | ||

|

Tourism increase cultural exchange between tourists and residents |

0.732 |

0.669 |

4.536 | ||

|

Tourism have positive impact on cultural identity community |

0.745 |

0.687 |

4.479 | ||

|

Perceived Cost |

0.891 |

0.918 |

0.650 | ||

|

Tourism increase in crime rate |

0.758 |

0.659 |

2.033 | ||

|

Tourism increase in traffic congestion |

0.845 |

0.768 |

2.525 | ||

|

Tourism increase in noise and pollution |

0.762 |

0.682 |

2.036 | ||

|

Tourism high spending tourist negatively affect local’s living style |

0.819 |

0.724 |

2.337 | ||

|

Tourism have negative effects on local culture |

0.867 |

0.780 |

2.916 | ||

|

Tourism locals suffers from living in a tourism destination |

0.781 |

0.656 |

2.071 | ||

|

Residents-Tourism Enterprises Conflict |

0.874 |

0.905 |

0.613 | ||

|

I feel annoyed as tourism business have changed local traditional lifestyle |

0.761 |

0.648 |

2.154 | ||

|

I feel annoyed as tourism business have reduced community cohesion |

0.788 |

0.666 |

2.152 |

|

Construct/Items |

Factor Loading (>0.7) |

CA (>0.7) |

CR (>0.6) |

AVE (>0.5) |

VIF (<5) |

|

Tourism businesses must share more economic benefit with locals |

0.791 |

0.683 |

2.282 | ||

|

I am frustrated as external investors have controlled local tourism resources and activities |

0.733 |

0.625 |

1.722 | ||

|

I am frustrated as tourism business have polluted local environment |

0.804 |

0.718 |

2.649 | ||

|

Tourism businesses disrupts the original landscape |

0.819 |

0.719 |

2.272 |

Table 3. Discriminant validity index for latent variables (Fornell and Larcker Criterion)

CI PB PC REC

|

CI |

0.879 | |||

|

PB |

0.557 |

0.743 | ||

|

PC |

0.293 |

0.021 |

0.806 | |

|

REC |

-0.345 |

-0.411 |

0.049 |

0.783 |

Note: The bold numbers represent the square root of AVE value.

Table 4. Discriminant validity index for latent variables (HTMT value)

|

CI |

PB |

PC |

REC | |

|

CP | ||||

|

PB |

0.607 | |||

|

PC |

0.316 |

0.111 | ||

|

REC |

0.384 |

0.455 |

0.117 |

The convergent validity and discriminant validity of each latent variable were supported. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were 0.772, 0.552, 0.650 and 0.613, respectively (Table 2), greater than 0.5 and demonstrating a high level of internal consistency (Chin, 1998; Hock & Ringle, 2010; Wong, 2013). The discriminant validity was presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The square root of the AVE of each construct was higher than the correlation coefficient between any two constructs,

indicating discriminant validity of the scale (Fornell & Larcker, 1981); the HTMT coefficients were lower than 0.9 (Henseler et al., 2015).

Structural model

In order to test the hypothesis, bootstrapping technique was performed on smart PLS software. The repeat sample size was 5000 (Henseler et al., 2009). The structural relationship and its impact are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Results of the structural path model

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

Estimate |

T value |

P Values |

|

H1 |

PB -> REC |

-0.293 |

5.117 |

0.000 |

|

H2 |

PC -> REC |

0.119 |

2.291 |

0.022 |

|

H3 |

CI -> REC |

-0.216 |

3.501 |

0.000 |

|

H4 |

CI -> PB -> REC |

-0.163 |

4.856 |

0.000 |

|

H5 |

CI -> PC -> REC |

0.035 |

2.038 |

0.042 |

The inner model suggests that:

The perceived benefit directly, negatively and significantly affects resident -tourism enterprise conflict (β = -0.293, t = 5.117 > 1.96; p value = 0.000 < 0.005). So, H1 is supported.

The perceived cost directly, positively and significantly affects resident -tourism enterprise conflict (β = -0.119, t = 2.291 > 1.96 and p value = 0.022 > 0.005). This means H2 is not supported.

Community involvement directly, positively and significantly affects resident - tourism enterprise conflict (β = -0.216, t = 3.501 > 1.96 and p value = 0.000 < 0.005). This means H3 is supported.

Community involvement indirectly, negatively, and significantly affects resident - tourism enterprise conflict through perceived benefit (β = -0.163, t = 4.856 > 1.96 and p value = 0.000 < 0.005). Thus, H4 is supported.

Community involvement indirectly, positively, and insignificantly affects resident - tourism enterprise conflict through perceived cost (β = 0.035, t = 2.038 > 1.96 and p value = 0.042 > 0.005). Accordingly, H5 is not supported.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Based on extended SET, the authors proposed a framework to analyse the antecedent factors of resident – tourism enterprise conflict. Following research process http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

suggested by Churchill (1979) and Wang et al., (2007), the study has developed a scale of conflict between residents and tourism businesses with 6 items. The study proved that the relationship between community involvement, residents’ perceived benefit and perceived cost with conflict between residents and tourism enterprises. The finding is the basis for following implication:

The role of residents' perceptions

Residents' perceptions of tourism benefits have a strong impact on residents – tourism enterprise conflict. The more benefits residents perceive, the less likely they are to oppose tourism businesses. Thus, to limit residents – tourism enterprise conflict, authorities should focus on actions to increase resident perceived benefits about tourism industry, and help them recognize the value of each other. To do this, the two groups must learn about the other party’ interest and come up with a mutual beneficial compromise. They may also ask a third party to act as an intermediary to find out the goals and interests of the parties, thereby to make proposals for beneficial cooperation (Rubin, 1994). Local authorities (who act as intermediaries between tourism businesses and local communities) are the best facilitators to connect the parties and help them understand each other, create consensus among groups, thereby to promote a more

effective cooperation or to form future alliances. Local authorities need to understand the needs, interests and concerns of each party, thereby building an integrated mechanism and policy that can meet the aspirations of the stakeholders. Each locality needs to have clear, consistent regulations and require the involved parties to comply. The government, with its power in the process of planning and attracting investment, needs to bear in mind that residents’ life quality must be their top concern.

Also, residents need to confer with tourism businesses on the cooperation mechanism and revenue sharing. The community will preserve natural landscapes along with traditional culture, protect natural environment, and create a beautiful destination image to attract tourists for businesses. In the reciprocation, tourism businesses who take advantage of local cultural values must share benefits with residents. They must help locals to preserve local culture and festivals, protect historical sites and natural landscapes.

In addition, enterprises must strictly comply with regulations on environmental protection, train and recruit locals with reasonable remuneration. Businesses should prioritize local labor to create job opportunities for locals and help them receive benefits from tourism development.

The role of resident involvement

Residents involvement is the determinant of sustainable development. Residents involvement has a direct and negative impact on residents - tourism enterprises conflict. It also affects residents' perceptions of tourism benefits, thereby indirectly affects the conflict between residents and tourism businesses. Therefore, in order to reduce conflicts between these two

groups, maximizing resident’s involvement is a very important solution. This findings supports the conclusion of various studies, eg: (Bhalla et al., 2016; Connor & Gyan, 2020; Curcija et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2019). When residents are involved in tourism (whether directly or indirectly), they have more opportunities to receive benefits, especially the economic ones (income, job opportunities, business start-up opportunities). This also contributes to improve residents’ life quality, especially in remote and mountainous areas.

In short, residents and tourism enterprises are important stakeholders at each tourism destination. Beside cooperation, there two groups may dispute with each other in all aspects of sociocultural, economic and environmental. This conflict may be just latent or have been exploded with hostile behaviors. To resolve conflicts, antecedent factors, including resident’s involvement, perceived benefit and perceived cost must be concerned seriously.

REFERENCES

Aas, C., Ladkin, A., & Fletcher, J. (2005). Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 28–48.

Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.an-nals.2005.03.001

Apostolidis, C., & Brown, J. (2021). Sharing Is Caring? Conflict and Value Codestruction in the Case of Sharing Economy Accommodation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 1–29.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Bearden, W. O., Hardesty, D. M., Rose, R. L., Bearden, W. O., Hardesty, D. M., & Rose, R. L. (2001). Consumer SelfConfidence: Refinements in Conceptualization and Measurement. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 121– 134.

Bearden, W. O., Netemeyer, R. G., & Teel, J. E. (1989). Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 473–481.

Bhalla, P., Coghlan, A., & Bhattacharya, P. (2016). Homestays’ contribution to community-based ecotourism in the Himalayan region of India. Tourism Recreation Research, 41(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.20 16.1178474

Butler, R. W. (1980). The Concept of A Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources Change on a remote island over half a century View project. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12.

https://www.researchgate.net/publi-cation/228003384

Canavan, B. (2017). Tourism stakeholder exclusion and conflict in a small island. Leisure Studies, 36(3), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.20 16.1141975

Ceballos-Lascurain, H. (1996). Tourism, ecotourism, and protected areas: The state of nature-based tourism around the world and guidelines for its development. IUCN: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Chen, C.-Y. (2018). Modeling resident attitudes toward the Chinese inbound tourist market. Journal of China Tourism Research, 14(2), 221–241.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

Choi, H. S. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 380–394.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875052 74651

Churchill, G. A. J. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Connor, C., & Gyan, P. N. (2020). Connecting landscape-scale ecological restoration and tourism: stakeholder perspectives in the great plains of North America. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 0(0), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.20 20.1801698

Curcija, M., Breakey, N., & Driml, S. (2019). Development of a conflict management model as a tool for improved project outcomes in community based tourism. Tourism Management, 70, 341–354.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2018.08.016

Daskalakis, S., & Mantas, J. (2008). Evaluating the impact of a service-oriented framework for healthcare interoperability. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 136, 285.

Ebrahimi, S., & Khalifah, Z. (2014). Community supporting attitude toward community-based tourism development; non-participants perspective. Asian Social Science, 10(17), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n17p2 9.

Engström, C., & Boluk, K. A. (2012). The Battlefield of The Mountain: Exploring the Conflict of Tourism Development on the Three Peaks in Idre, Sweden. Tourism Planning and Development, 9(4), 411–427.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.20 12.726261

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4.

Fan, D. X. F., Liu, A., & Qiu, R. T. R. (2019). Revisiting the relationship between host attitudes and tourism development: A utility maximization approach. Tourism Economics, 25(2), 171–188.

https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166187 94088

Feng, X., & Li, Q. (2020). Poverty alleviation, community participation, and the issue of scale in ethnic tourism in China. Asian Anthropology, 19(4),

233–256.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.20 20.1778154

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gan, J.-E. (2020). Uncovering the Environmental and Social Conflicts Behind Residents’ Perception of CBT: A Case of Perak, Malaysia. Tourism Planning and Development, 17(6),

674–692.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.20 20.1749121

Gascón, J. (2012). The limitations of community-based tourism as an instrument of development cooperation: the value of the Social Vocation of the Territory concept. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(5), 716–731.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

Glasson, J., Godfrey, K., & Goodey, B. (1995). Towards visitor impact management: Visitor impacts, carrying capacity and management responses in Europe’s historic towns and cities. Avebury.

Goodwin, H., & Santilli, R. (2009). Community-Based Tourism: a success? ICRT Occasional Paper 11, 11, 1–37.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105.

Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism. Annals OfTourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.an-nals.2003.08.008

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed., Vol. 5, Issue 3). Prentice-Hall.

Hair, J F, Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th edn). Prentice-Hall.

Hair, Joe F, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123.

Hair, Joseph F, Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12.

Hardesty, D. M., & Bearden, W. O. (2004). The use of expert judges in scale development: Implications for improving face validity of measures of unobservable constructs. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 98–107.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variancebased structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hlengwa, D. C., & Mazibuko, S. K.

(2018). Community leaders around Inanda Dam, Kwazulu Natal, and issues of community participation in tourism development initiatives. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(1). https://www.sco-pus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85042477034&part-nerID=40&md5=66e30fd092fa73bf9 8558dd3b398aee3

Hock, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2010). Local strategic networks in the software industry: an empirical analysis of the value continuum. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 4(2), 132–151.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior in elementary forms. A primer of social psychological theories. Social Behavior, 488–531.

Jinsheng, Z., & Siriphon, A. (2019). Community-based Tourism Stakeholder Conflicts and the Co-creation Approach : Journal of Mekong Societies, 15(2), 37–54.

https://doi.org/10.14456/jms.2019.9

Jones, S. (2005). Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2), 303–324.

Jurowski, C., & Gursoy, D. (2004). Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 296–312.

Kaltenborn, B. rn P., Andersen, O., Nel-lemann, C., Bjerke, T., & Thrane, C. (2008). Resident attitudes towards mountain second-home tourism development in Norway: The effects of environmental attitudes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(6), 664–680.

Kinseng, R. A., Nasdian, F. T., Fatchiya, A., Mahmud, A., & Stanford, R. J. (2018). Marine-tourism development on a small island in Indonesia: blessing or curse? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(11), 1062–

1072.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.20 18.1515781

Ko, D., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents ’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23, 521–530.

Kreiner, N. C., Shmueli, D. F., & Gal, M. Ben. (2015). Understanding con fl icts at religious-tourism sites : The Baha ’ i World. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 228–236.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.04 .001

Lee, T. H. (2013). Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management, 34, 37–46.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2012.03.007

Lepp, A. (2007). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tourism Management,

28(3), 876–885.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2006.03.004

Liu, Q., Yang, Z., & Wang, F. (2017). Conservation Policy-Community Conflicts : A Case Study from Bogda Nature Reserve , China. 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081291

Lo, Y. C., & Janta, P. (2020). Resident’s Perspective on Developing Community-Based Tourism – A Qualitative Study of Muen Ngoen Kong Community, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(July), 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.0 1493

Mannon, S. E., & Glass-Coffin, B. (2019). Will the real rural community please stand up? Staging rural communitybased tourism in Costa Rica. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 14(4), 71–93.

McCool, S. F. (2009). Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change and messiness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 133–148.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802 495733

Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th Ed). Pearson.

Nicholas, L. N., Thapa, B., & Ko, Y. J. (2009). Residents’ perspectives of a world heritage site: The Pitons Management Area, St. Lucia. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 390–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.annals.2009.03.005

Nugroho, P., & Numata, S. (2020). Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 0(0), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.20 20.1755675.

Nunkoo, R., Kam, K., & So, F. (2016). Residents ’ Supportfor Tourism : Testing Alternative Structural Models. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875155 92972

Presenza, A., Del Chiappa, G., & Sheehan, L. (2013). Residents’ engagement and local tourism governance in maturing beach destinations. Evidence from an Italian case study. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(1), 22–30.

Prior, D. D., & Marcos-Cuevas, J. (2016). Value co-destruction in interfirm relationships: The impact of actor engagement styles. Marketing Theory, 16(4), 533–552.

https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931166 49792

Prosser, R. (1994). Societal Change and the Growth in Alternative Tourism, Ecotourism: A Sustainable Op-

tion?(E. Cater & G. Lowman, eds.), John Wiley, Chichester.

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ramayah, T. (2015). A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 335–345.

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ringle, C. M., Jaafar, M., & Ramayah, T. (2017). Urban vs rural destinations : Residents ’ perceptions , community participation and support for tourism development. Tourism Management, 60, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2016.11.019

Rubin, J. Z. (1994). Models of Conflict Management. Journal of Social Issues, 50(1), 33–45.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb02396.x

Sebele, L. S. (2010). Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino Sanctuary

Trust, Central District, Botswana. Tourism Management, 31(1), 136–

146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2009.01.005

Sekhar, N. U. (2003). Local people’s attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. Journal of Environmental Management, 69(4), 339–347.

Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49.

Simmons, D. G. (1994). Community participation in tourism planning. Tourism Management, 15(2), 98–108.

Sirivongs, K., & Tsuchiya, T. (2012). Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR. Forest Policy and Economics, 21, 92–100.

Sitikarn, B. (2008). Ecotourism SMTEs opportunities in Northern Thailand: A solution to community development and resource conservation. Tourism Recreation Research, 33(3), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.20 08.11081553

Tao, T., & Wall, G. (2009). Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tourism Management, 30(1), 90–98.

Tesfaye, S. (2017). Challenges and opportunities for community based ecotourism development in Ethiopia. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(3). https://www.sco-

pus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85029021077&part-nerID=40&md5=76d0419d877215ba 9e9c3e91ad2202ec.

Thomas, K. W. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of Indus- trial and Organizational Psychology (pp. 889– 935). Rand McNally.

Timur, S., & Getz, D. (2008). A network perspective on managing stakeholders for sustainable urban tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(4), 445– 461.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110810 873543

Wang, L. (2021). Causal analysis of conflict in tourism in rural China: The peasant perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39(July),

100863.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.10 0863

Wang, L., & Yotsumoto, Y. (2019). Conflict in tourism development in rural China. In Tourism Management (Vol. 70, pp. 188–200).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2018.08.012

Wong, K. K.-K. (2013). Partial least

squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1), 1–32.

Xu, K., Zhang, J., & Tian, F. (2017). Community leadership in rural tourism development: A tale of two ancient Chinese villages. Sustainability (Switzerland), 9(12).

https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122344

Xue, L., & Kerstetter, D. (2018). Discourse and Power Relations in Community Tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 57(6), 757–768.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875177 14908.

Yang, J., Ryan, C., & Zhang, L. (2013). Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism. Tourism Management, 35, 82–93.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2012.06.002

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352.

Zhang, C., Fyall, A., & Zheng, Y. (2015). Heritage and tourism conflict within world heritage sites in China : a longitudinal study. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(2), 110–136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.20 14.912204

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

143

e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback