Social Network and Small Business Sustainability: A Case Study in Borobudur Temple Tourism Park

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.8. No.2. (2021): 229-236

Social Network and Small Business Sustainability: A Case Study in Borobudur Temple Tourism Park

Putri Usmawati1, Yanu E. Prasetyo2*, Muhammad Fedryansyah1

1Padjajaran University, Indonesia 2National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia

*Corresponding Author: yanu002@lipi.go.id

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24922/eot.v8i2.77768

Article Info

Submitted:

August 31th 2021.

Accepted:

September 19th 2021.

Published:

September 30th 2021

Abstract

This study aims to determine the characteristics and patterns of the social network of souvenir traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park and explore the relationship between social networks and the sustainability of the souvenir merchants’ business. In this qualitative study, researchers conducted data collection (observation and in-depth interview) between January 2018 and January 2019 before the COVID-19 outbreak hit the area. Social network data and information from the interview were analyzed and visualized with the Node-XL computer program. Our findings showed that the formation of a social network of souvenir merchants and small traders was based on kinship, friendship, interests, and contractual relationships. The structures that are maintained and developed in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area contain interrelated actors. While the relationship between suppliers and merchants is diagonal, the social interaction and network pattern among small traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park is horizontal. Souvenir merchants and small traders in the Borobudur Temple tourism park are always maintaining their social capital to survive in their business. We can learn that each merchant is closely connected with some key fellow merchants and small or medium traders from this pattern. This network and ties among small traders can also determine trust and social capital between actors. Through each small traders’ social network, a business network based on interest, kinship, friendship, and contractual relationships can be unraveled.

Keywords: Borobudur Temple, Tourism Park, Indonesia, Social Network, Small Traders, Business Sustainability, Trust

INTRODUCTION

Each actor (merchant, supplier, small traders, buyer, and local business authorities) has a unique and distinctive relationship pattern in a tourism-based business setting. A relationship between traders can be seen in the procurement, distribution,

and pricing of goods, including selling locations and other social and economic opportunities (Listiana, 2005). For instance, the relationship between small-traders and suppliers is not only on souvenirs distribution but also on exchanging information regarding the latest types of merchandise and information about other trading part-

ners. The interaction of various actors in the small business network creates unique patterns and relationships.

Research on merchants’ social networks in Indonesia has been conducted by several scholars, including Bukhari (2017), who examined the social network of street vendors (PKL) in Banda Aceh City. Bukhari’s research results found that the street vendors are “nano units” that create an informal buying and selling process and pattern scattered in society. The informal network is vital for street vendors since it can reduce the risk of losing work. This informal social network is seen as being able to create opportunities for poor people to escape poverty. From the aspect of communication, the existence of similarity in language seems to make it easier for small traders to disseminate information, chat with each other, gossip, complain, and joke between them (Vera Sufyanti, 2007). Networks and trust are also the most critical aspects of small business social capital, as Parasmo and Utami (2017) found in the antique dealer network pattern in Surabaya.

The Borobudur Temple Park area itself is a unique business setting. Listiana (2005) states that the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park’s existence has a positive impact on residents’ economy, such as expanding business opportunities, opening up new jobs, increasing income, and the creativity of traders in developing their small businesses. However, an important tourist attraction such as the Borobudur Temple also impacts rising prices for goods and services around the area.

The informal market’s social networks in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park consist of suppliers, traders, buyers, customers, and merchant associations. This existing social network directly affects the sustainability of people’s businesses in this area, especially small and medium enterprises that rely on the Borobudur Temple’s brand and icon. This paper aims to deter-

mine the characteristics and patterns of the social network of souvenir traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park and explore the relationship between social networks and the sustainability of the souvenir merchants’ business in this area.

METHOD

Primary data sources were obtained directly from the field through participatory observations and in-depth-interviews with informants. Researchers observed the physical conditions of the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park Area (location of the market, the arrangement of booths, types of merchandise, etc.) and other actor activities (interactions that occurred between small traders and buyers). Data collection was conducted between January 2018 to January 2019 before the COVID-19 outbreak hit the area. In this study, researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 12 key informants. Some additional data dan information was taken from several sources such as books, newspapers, the internet, and PT. Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. Informants are divided into four categories, (1) Small traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park (2) Souvenir merchants or suppliers - people who sell merchandise to small traders. (3) Buyers and visitors of Borobudur Temple, and (4) the Chairman of the Association of Souvenir Traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. We used Node-XL computer program to visualize our network data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The history of small traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area began around the 1970s. Merchandise sold at that time was batik clothes, sungu handicrafts in the form of a ladle, rakes, crafts made of Batok shells, and hats. Suppliers of merchandise came from Pekalongan, Pucang,

and Gombong (Central Java). Small traders are free to sell souvenirs in the area. There is no arrangement for stalls. In 1975 Regional Government Market Service of Magelang Regency began to collect fees from small traders. The outdoor market location is around the base of the Borobudur Temple - formerly known as the Indras, named by the Indras restaurant and inn. Small traders were selling their souvenirs and crafts around the Indras’ restaurant and motel. In 1982 traders were relocated near the Borobudur Bus Terminal. The Magelang Regency Market Service offers two options to all small and informal traders: joining PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur, placed in the east of Borobudur Terminal, and those who followed the Magelang Regency Government, set near the Borobudur Bus Terminal (see figure 1).

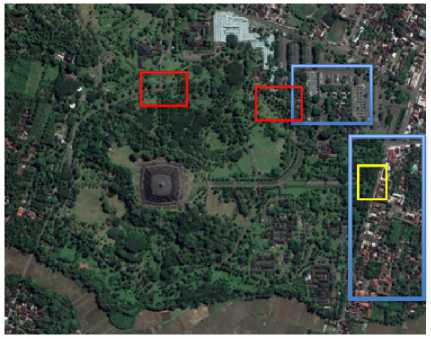

Figure 1. The Borobudur Temple Tourism Park Area from above. Entrance (yellow), exit (red), and outdoor souvenir’s market (blue). Source: Google earth

In 1985 the small traders were again moved to the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. Small traders who participate in PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur are entitled to a kiosk or booth in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area. In contrast, small traders who participate in the Magelang Regency Government do not get a booth in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park Area.

There are 100 kiosks in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. With the movement of these stalls, there was a huge change for small traders. There was no organization of small traders at that time. After moving to the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area, a merchant and small traders association was formed.

The association becomes a forum for joint activities for small traders. The association programs include a family gathering, picnics, and representing meetings for small traders when there is a policy from the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park management. Besides, there are also activities to increase small traders’ skills and capacities such as English and French language training. At that time, many foreign tourists visited Borobudur Temple, and these tourists often bought souvenirs. Around 2000 the association functioned as representative of small traders and providing information on policies taken by the management of PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur.

Based on the type of merchandise, small traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area consist of souvenir smalltraders (clothes, bags, necklaces, bracelets, wood carvings, miniatures of Borobudur Temple, chains in the form of Borobudur Temple, etc.), hat, fruits, food and beverage kiosk, umbrella renters, and stroller tenants. Meanwhile, small traders are separated into three different locations: (1) east gate market, (2) central gate market, and (3) west gate market. East gate market are located around the east exit gate of Borobudur Temple. Central door market are located around the exit gate of Borobudur Temple, and west gate market are located around the exit gate of Borobudur Temple in the west (see figure 1).

Based on stalls’ size, a small business in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area consists of kiosk traders, stall traders, and hawkers. Kiosk traders are small traders who occupy permanent stalls that have

been provided by the management of PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur since 1985 (100 stalls in total). One stall occupied by 2-4 small traders. The kiosk vendor pays the rental fee to PT. Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur in an amount that varies depending on its size, which is around Rp. 60,000 to Rp. 150,000 per month (2019). Based on the interview with Mrs. SR (kiosk owner), the heirs can inherit the kiosk (children/ grandchildren of the family). However, this policy is not stated in the contract. Stall traders are small traders who occupy a 3 x 2-meter stall. These stall traders also have to pay fifteen thousand rupiahs (collected by the association’s chairman and then distributed to PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur). The hawkers are informal traders who sell their merchandise by handing them out. The merchandise sold by hawkers also varies. Some sell clothes, crafts, accessories, bracelets, necklaces, hats, key chains, umbrellas, fans, and even fruits. These hawkers often have problems with kiosk traders and stall traders because they often sell their products to visitors of the kiosk or the stalls.

Figure 2. Small traders are paying debts to suppliers and exchanging information with other traders. Doc: Putri Usmawati (2019)

Small traders in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park area open their business in the morning, at 07.00 WIB. On holidays, small traders begin to open their kiosks or stalls at 06.00 WIB. At noon, traders usually use their break time to pray, lunch, or go home to see children who have returned from school. And then they returned to open the business again until 17.00 WIB.

There are certain days, such as during Idul Fitri, Vesak, Chinese New Year, or Christmas and New Year holidays. Small traders close their stalls at 21.00 WIB. Some small traders stay overnight at the stalls when the park is crowded with tourists. For small traders, holidays are the best opportunity for them to gain multiple profits compared to regular days.

There is a couple of large-scale supp-liers/wholesalers in the network. This wholesale supplier has merchandise in bulk. Some are self-produced (home industry scale), and some are taken from the producers. Small traders and suppliers have been trading for more than ten years. Small traders who trade under ten years are usually new traders or second-generation traders. Small traders who are still in business for more than 20 years have a unique strategy for sustaining their family business. These skills and strategies include the ability to maintain relationships with suppliers, the ability to manage finances and business strategies. According to key informants, trust is essential in establishing good relationships with fellow traders and suppliers. Traders can find it easily both in the financial capital and in products. In terms of financial support, traders are usually given money in the form of merchandise and are paid 1 or 2 months later. Small traders who are trustworthy can take more inventory than other small business owners.

Small Traders Networks

Several types of networks formed in souvenir traders’ social networks in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. Based on social relationships, small traders’ systems are composed of kinship, friendship, shared interests, and contract-based affinities. It can be understood about family, relatives, friends, and neighbors’ critical role in developing and maintaining social networks carried out by merchants and small traders because businesses are passed down from

generation to generation by their families and relatives.

Network of kinship

An example of a social network based on kinship is the relationship between Mrs. SR, and Mr. R. Mrs. SR is the older brother of Mr. R. Initially, R worked as a staff at a motel in Borobudur. However, since getting married and then having children, R decided to quit his workplace because his salary could not meet his wife and children’s needs. She complained to her brother (Mrs. SR) about her family’s economic problems. Mrs. SR advised R to help her business while waiting for another stall or kiosk that could be occupied. For approximately one year, R helped Mrs. SR. R received information that there was an empty stall that could be settled. Then R rented the booth and sold various souvenirs, especially those made of teak wood. Because based on her experience helping Mrs. SR, R saw that the opportunity to sell teak wood was profitable. R started looking for information on teak wood suppliers. Mrs. SR provided information about the supplier’s location and supply system. Mrs. SR introduced R to the supplier. The limited access to information about the empty or occupied stalls is known only by people in the network. It shows that networks based on kinship are essential for exchanging information between actors in the network.

Network of friends

There is also a network that is formed from friendship. Some small traders depend on friends when they need money or financial support. Even though they cannot borrow a large amount, they think this is very effective because borrowing money from friends does not incur interest, like borrowing money from a bank or a pawnshop. This is motivated by a reciprocal relationship. As experienced by a small trader, “A.” Due to limited capital, if

A has difficulty paying merchandise debts to suppliers, he will borrow money from friends, mostly fellow small traders. There was no written agreement when he borrowed money, only based on trust. However, merchant A always paid his debt even with installments. He revealed that the trust that had been entrusted by his friend would not be denied to maintain the friendship. Here we can see the unwritten responsibility of a network based on a personal relationship. Friendship is also useful in business relationships, including obtaining information about suppliers’ names, addresses, and prices. This means that social capital in the form of trust in friendship helps develop business and networks. Friendship networks can arise due to various reasons, such as locality (originating from the same hometown), common fate, and shared interests. The values of reciprocity, trust, and cooperation characterize friendship. This can be seen when a small trader takes a lot of merchandise from one supplier, then repeatedly does not pay off the debt. He will be “punished.” If there is a problem with the supplier, other traders do not want to help him because he has been warned.

Network with shared-interests

The second aspect of forming social networks is based on shared-interests, especially economic interest, in maintaining their business. Small traders establish and maintain mutual relationships with their business partners or fellow traders, suppliers, and buyers. For example, small traders try to build familiarity with the product with suppliers and hope that they will get and owe the merchandise. Having “debt” to suppliers is a common practice for small traders to maintain business relationships. By having debt for inventory, the supplier would come to his stall every week. Small traders will use it to ask about new merchandise while paying off the previous debt. In this relationship, the suppliers gain

their profit, and on the other hand, the small traders can also maintain the relationship and trust with suppliers.

Contract-based relationship

There is also the type of network based on contractual relationships. Traders often feel worried about the policies of PT. Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur management, which is sometimes considered not to be pro-small traders. The small traders› community hopes that the association›s leader will be able to convey their aspirations for the policy issued by PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur. The Chairperson of the Association has the power to talk and bargain with PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur regarding market relocation, renovation of merchant stalls, and other regulations.

Network, Trust and Business Sustainability

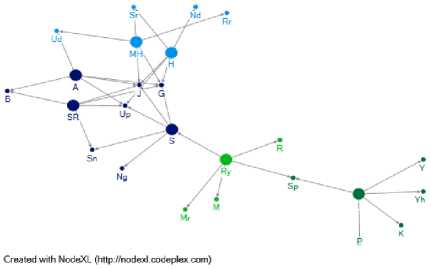

The network below (figure 3) shows the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park’s souvenir traders’ network. The larger nodes are small traders who become “key actors” in the networks. A key actor is a person entrusted by the merchant to distributes information about the arrival of new merchandise. Several types of suppliers only supply merchandise to specific traders, with the excuse that their inventory remains exclusive. Usually, these key actors are also used by other small traders to obtain merchandise from these suppliers.

The key actor in this network is SR’s mother. Several big suppliers, such as Mr. B, often contact Mrs. SR, who comes and visits every three months from Solo, Central Java.

“Usually, Mr. B contacted me, asked about any merchandise that had run out, and gave me the news that there was new merchandise. Later I will tell other traders who I trusted. If there are traders in debt and don’t want

to pay, I feel uncomfortable with Mr. B. I am taking responsibility. That’s how it feels”.

Figure 3. Social networks of informants in the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park

According to Reader (1964), connectedness is a line of communication between the ego and between one individual and another in social networks to establish cooperation as a means for business continuity. We can see this form of connection from the communication aspect. Traders usually communicate with fellow traders and suppliers directly/face-to-face and indirectly via SMS, telephone, or What-sApp. The ease of communication allows the exchange of information between small traders and business partners. In the relationship between small traders, density can be described by the thickness of relationships among actors. With this pattern, small traders know each other, understand each other, and generate trust. In addition to business relations, they also develop social relationships, such as coming and supporting when a disaster hits, attending a merchant’s child marriage, or merely being friends to confide in among small traders.

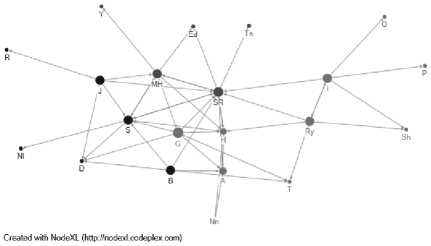

Figure 4 shows that there are differences in network groups based on their color. Larger nodes are small traders who are the key informants in this study; smaller nodes are those who become the network of key informants. From the network map above, Mrs. SR has the most ties and links. She

has close relations with various types of small traders, both kiosk and stall traders. The ease of communication allows the exchange of information both with fellow small traders with suppliers. Trust between them is useful for the merchant’s business’s continuity. The social network that is formed can help in terms of social and financial capital. After all, cooperation among them can make it easier to run a small business in Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. For small traders, social network is a tool to facilitate business sustainability. From the aspect of human resources, the social networks that occur among them must be cooperative to benefit all parties mutually.

Figure 4. The centrality of informant social networks at the Borobudur Temple Tourism Park. The centrality degree is defined as the number of ties that a node (small traders) has.

CONCLUSION

The formation of social networks among merchants and small traders’ community in Borobudur Temple Tourism Park was usually based on kinship, friendship, interests, and contract-based relationships. Small traders have relatively high meeting frequencies and intensity. Also, there is physical closeness, both in the business’s residency and location—these family bonding and friendship relations can also create solidarity and higher emotional connections among them. The relationship among souvenir traders in the Borobudur Temple

Tourism Area is horizontal. Meanwhile, the relationship between suppliers and small traders, small traders and the association’s leader is a diagonal relationship. The business continuity and sustainability of merchants in Borobudur is influenced by social capital and social networks, which are inseparable. In other words, small traders at Borobudur Temple Tourism Park must always maintain trust between them and expand their social capital by developing new social networks to support business sustainability.

REFERENCES

Ageng, Elmas. (2009). Tinjauan terhadap Relokasi Pedagang Kaki Lima sebagai bentuk pengelolaan Kawasan Heritage, Studi Kasus: Zoning Penyangga Kawasan Candi Borobudur. Jakarta: Universitas Indonesia.

Agusyanto, Ruddy. (2007). Jaringan Sosial dalam Organisasi. Jakarta: Rajawali Press.

Budiarti S, Meillany. (2017). Jaringan Sosial Kebertahanan Kegiatan Usaha Industri Kecil di Desa Sukamaju Kecamatan Majalaya Kabupaten Bandung. Bandung: Universitas Padjajaran.

Bukhari. (2017). Pedagang Kaki Lima (PKL) dan Jaringan Sosial : Suatu Analisis Sosiologi. Aceh: Jurnal Sosiologi Universitas Syah Kuala.

Damsar. (2015). Pengantar Teori Sosiologi. Jakarta: Kencana.

Damsar & Indriyani. (2016). Pengantar Sosiologi Ekonomi Edisi Kedua. Jakarta: Kencana.

Eriyanto. (2014). Analisis Jaringan Komunikasi. Jakarta: Kencana.

Jackson, Matthew O. (2008). Social Economic Networks. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

J Clyde, Mitchell. (1969). Social Network in Urban Situation: Analyses of Personal Relationships in Central African Towns. Zambia: University of Zambia.

Listiana, Afri. (2005). Pengaruh Obyek Wisata Candi Borobudur terhadap Perilaku Sosial Ekonomi Pedagang di Kawasan Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur Kabupaten Magelang. Semarang: Universitas Semarang.

Martono, Nanang. (2016). Metode Penelitian Sosial Konsep konsep Kunci. Jakarta: Rajawali Press.

Moleong, Lexy J. (2002). Metodologi Penelitian Kualitatif. Bandung: PT Remaja Rosdakarya.

Mustofa, Bisri & Maharani, Elisa Vindi. (2008). Kamus Lengkap Sosiologi. Yogyakarta: Panji Pustaka.

Parasmo, T. H. (2017). Jaringan Sosial Barang Antik di Kota Surabaya. Jakarta:

Paradigma.

Putra, Johan Jatu Wibawa. (2010). Jaringan Sosial Pengusaha Tempe dalam Kelangsungan Usaha di Debegan. Surakarta: Universitas Sebelas Maret.

Ritzer, George & Goodman, Douglas J. (2005). Teori Sosiologi Modern. Jakarta: Kencana.

Scott, John P. (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. London: SAGE Publication.

Soepoetro, Bintang. Y. (2009). Jaringan Sosial Para Pelaku Sektor Ekonomi Informal. Depok: Universitas Indonesia.

Soekanto, Soerjono. (1985). Sosiologi Suatu Pengantar. Jakarta: Rajawali.

Subhan, Ahmad. (2017). Pelaksanaan Transparansi Pemerintah Daerah dalam Perspektif Jaringan. Bandung: Universitas Padjajaran.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

236

e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback