Assessing the Effectiveness of Technology in Destination Marketing during the COVID-19 Pandemic

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.8. No.2. (2021): 149-160

Assessing the Effectiveness of Technology in Destination Marketing during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Tinashe Chuchu*

University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

*Corresponding Author: tinashechuchu4@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24922/eot.v8i2.74597

Article Info

Submitted:

June 24th 2021.

Accepted:

September 21th 2021.

Published:

September 30th 2021

Abstract

Technology has played an important role in tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic expanded this role as well as its importance. This research therefore explores the impact that technology made in destination marketing during the time of the pandemic. This research explores the pandemic’s first year of widespread global coverage both in the media and in academic literature. An extensive review of technology use in destination marketing and COVID-19’s impact on destination marketing is conducted. The present research is mainly concerned with the first year of the pandemic but is not limited to that period since the adoption of technology in tourism existed before the pandemic but increased due to the pandemic. This research made every attempt to investigate this phenomenon. Based on findings of the research, future research direction is proposed.

Keywords: technology in tourism, destination, marketing, management, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The tourism industry has adopted the use of technology over the years (Buhalis & O’Connor, 2005; Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, 2017; Werthner & Klein, 1999). Some tourism research that incorporated technology, has investigated acceptance of knowledge sharing systems in the travel and tourism websites (Noor, Hashim, Haron & Ariffin, 2005) while other research explored how technology revolutionised the tourism industry (Buhalis & O’Connor, 2005). Yu, Xie and Wen (2020) conducted tourism research that explored the role of colour psychology on the social media platform, Instagram. Furthermore, consumer acceptance of information technology in tourism

was also reviewed (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, 2017; Werthner & Klein, 1999). Gretzel, Fuchs, Baggio, Hoepken, Law, Neidhardt, Pesonen, Zanker and Xiang (2020) emphasised that the outbreak of COVID-19 called for transformative (electronic tourism) ETourism. Different perspectives on the pandemics impact were explored. Qiu, Park, Li and Song (2020) reviewed the pandemics social impact on tourism. Fotiadis, Polyzos and Huan (2021) explored the minor negative effects of the pandemic to the extreme devastating effects that the global pandemic had caused. This research began one of the first seminal studies that advocated serious adoption of E-Tourism in the wake of the global spread of COVID-19 this making the pandemic a central tourism issue.

The primary research objective of this research was to understand the impact that was made by the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism while the secondary objective was to investigate the effectiveness of technology in destination marketing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Foo, Chin, Tan and Phuah (2020) investigated the impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. This tourism research continued to make the link between COVID-19 and the tourism industry an increasingly pertinent issue especially when it comes to the marketing of destinations. Online social networking sites have become the most commonly used sites on the internet (Miguéns, Baggio & Costa, 2008). The use of social media has emerged to become a paramount social phenomenon and an international business trend (Cheng & Edwards, 2015; Hays, Page & Buhalis, 2013). The growing role of social media in tourism has been increasingly an emerging research topic (Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014). A social media platform that has become popular with travellers is Instagram (Gumpo, Chuchu, Ma-ziriri & Madinga, 2020). Similarly, there has been an increased interest on social media as a repository of research data traveller decision-making process (Hudson & Thal, 2013), electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) (Ye, Law, Gu & Chen, 2011), and travel recommendations (Kurashima, Iwata, Irie & Fujimura, 2010). User generated content is acknowledged as having paramount importance to the tourism industry (Ake-hurst, 2009; Milano, Baggio & Piattelli, 2011). Destination marketing is a central issue in the development of a destination and in the competition to attract visitors (Hvass, 2014). This issue has seen a rise of the adoption of technology in growth and development (Buhalis, & Law, 2008; Li, Robinson & Oriade, 2017). Tourists’ attitudes towards a destination tend to be shaped by that particular destination (Gumpo et al., 2020). Li et al. (2017) explored the use

on the technology in tourism from the year 2000 onward while Buhalis and law (2008) investigated the progress in the use of information technology in tourism. Furthermore, some has research has gone further to assess the impact of technology in tourism (Pollock, 1995). A destination as a concept comprising of functional characteristics related to the more tangible aspects of a place as well as the psychological appearances, relating to the intangible characteristics of that place (Sonnleitner, 2011). In addition, it is suggested that the first call of action in creating a viable destination brand image is through understanding tourists’ images of the destination. As far as destination marketing and the application of technology in tourism is concerned, tourism experiences have been a key issue. Neuhofer, Buhalis and Ladkin (2012) examined how technology enhanced tourist destination experiences. The idea of developing amusing and memorable experiences for tourists constitutes a prevalent concept in the tourism industry (Neuhofer et al., 2012). More recently the COVID-19 pandemic as played a major role in tourism literature (Fotiadis et al., 2021; Gretzel, et al., 2020; Kaushal & Srivastava, 2021; Qiu et al., 2020; Sigala, 2020). The following section discusses the studies literature.

LITERTATURE REVIEW

Technology in Tourism

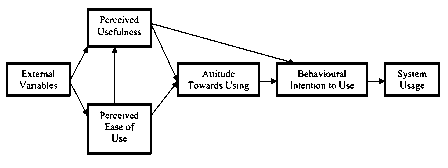

The technology acceptance model (Davis, 1989) was originally development as an information systems framework but was over the years it has been applied to various fields of study. In marketing (Rau-niar, Rawski, Yang & Johnson, 2014), business management (Dulcic, Pavlic, & Si-lic, 2012) and education (Ibrahim, Leng, Yusoff, Samy, Masrom & Rizman (2017). In tourism, Chen and Tsai (2019), El-Goha-ry (2012), Herrero and San Martín (2012). Noor et al. (2005) and Phatthana and Mat

(2011) adapted the use of the technology acceptance model. The following model presents the tourism adaptation of the technology by Noor et al. (2005). The model proposed by Noor et al. (2005) remained the same as the original proposed by Davis (1989), but was applied to a tourism context.

Figure 1. The Technology Acceptance

Model Adapted for Tourism Research

Adopted from Davis (1989) and Noor et al. (2005)

The technology acceptance model has been used extensively (Herrero & San Martín, 2012; Lee, Kozar & Larsen, 2003; Noor, Hashim, Haron & Ariffin, 2005; Uso-ro, Shoyelu & Kuofie, 2010). Lee, Kozar and Larsen (2003) discussed the technology acceptance model in relation to its past, present and future. The travel and tourism industry has arose as a major global economic player and information technology is crucial to this industry’s growth (Gret-zel & Fesenmaier, 2001; Noor, Hashim, Haron & Ariffin, 2005). The increased use of technology scope and use of technology has been evident. For instance, Herrero and San Martín (2012) developed a global model to test and explain the use of websites by users in rural tourism accommodations. Usoro, Shoyelu and Kuofie (2010) explored technology acceptance models use in etourism while Hanan and Putit (2014) research the marketing of tourism destinations through Instagram.

Online social networking evolved the approach to which tourists prepare for trips (Miguéns, et al., 2008). These websites allow users to engage with each other

and the service providers as well as provide reviews on service through platforms such as TripAdvisor (Miguéns, et al., 2008). Social media plays a key role in tourism, particularly on information search and decision-making travel behaviours (Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014). At least 84% of leisure travellers use the internet to plan their trips (Leung, Law, Van Hoof & Buhalis, 2013; Torres, 2010). Research on the impact of social media and online communities, such as Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter, on both society and the market place has gained popularity (Li & Bernoff, 2008; Qualman, 2009; Weber, 2009; Weinberg, 2009), including tourism (Hvass & Munar, 2012).

Destination Marketing and COVID-19 Impact on Tourism

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism and hospitality is unprecedented (Kock, Nørfelt, Josiassen, Assaf & Tsionas, 2020). Destination marketing is as a central concept in the future growth and sustainability of tourism destinations in an increasingly globalised and competitive market for tourists (UNWTO, 2011). Furthermore, destination image holds a key place in tourists’ decision-making and subsequent travel behaviour (Chuchu, Chiliya & Chinomona, 2018). Destination marketing, as a concept has been researched from different perspectives in past tourism research, for example, Murphy, Pritchard, and Smith (2000) and Miličević, Mihalič, and Sever (2016) examined destination destination competitiveness. Okumus, Okumus and McKercher’s (2007) examined the use food in marketing destinations, while Zhang, Wu, Morrison, Tseng, and Chens (2018) assessed how a country’s image influences a tourist’s individual evaluation of destination. Destination image has been confirmed to have an effect on travellers’ decisionmaking (Chen &Tsai 2007; Chuchu, 2020). The intricacy and interdependency among the key destination-marketing players

eventually leads to the development of various tourism-marketing alliances (Palmer & Bejou, 1995).

A cure for COVID-19 is currently not in existence (Yavuz & Ünal, 2020) and this has led to countries imposing travel restrictions on visitors through stringent restrictive measures in an attempt to curb the spread of the disease (Altuntas & Gok, 2021; Piguillem & Shı, 2020). The global wide spread of the COVID-19 pandemic led to the high cancellation rates, refunds of flights and accommodation bookings (Yu, Li, Yu, He & Zhou, 2020). This was a direct outcome of tourists’ perceptions of risk and travel restrictions (Yu et al., 2020). There is a vast amount of tourism literature covering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism (Altuntas & Gok, 2021; Foo et al., 2020; Fotiadis et al., 2021; Gretzel et al., 2020; Kaushal & Srivastava, 2021; Kock et al., 2020; Piguillem & Shı, 2020) among other scholarly works. This literature explored various perspectives on COVID-19 with Altuntas and Gok (2021) on domestic travel and quarantines while Foo et al. (2020) focused on tourism in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fotiadis et al. (2021) looked into tourism recovery from COVID-19, Gretzel et al. (2020) focused on post-COVID-19 tourism and Kaushal and Srivastava (2021) on COVID-19’s impact on India’s tourism. Kock et al. (2020) investigated the psychological effects COVID-19 impact on tourist while Piguillem and Shi (2020) assessed COVID-19 quarantine and testing policies.

Technology adoption in Tourism during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the tourism industry to adjust the way in which it operated and one of these was the increased utilisation of technology. Social media was adopted in tourism extensively to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic (Chloridiany, 2021). Social media has been

mainly publicly used as a tool for travel businesses and destination marketing organisations to maintain contact with tourists in order to generate desire to travel (Mar-ketResearch.com, 2021). Even though the war against COVID-19 is becoming less aggressive and restrictions are easing, it is evident there will be long-standing effects on traveller behaviour and the use of social media (MarketResearch.com, 2021). Yu et al. (2020) discussed the communication of the COVID-19 health crisis on social media. Furthermore, Yu et al. (2020) made this discussion possible through reviewing over 10 000 comments on social media regarding the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Numerous studies explored the adoption of technology in tourism during the pandemic. For example, Sharmin, Sultan, Badu-lescu, Badulescu, Borma and Li (2021) researched sustainable destination marketing networks on smartphone-based social media. Furthermore, An, Choi and Lee (2021) looked into traveller’s adoption of virtual travel experiences, destination marketing information quality and visit intention. Kumpu, Pesonen and Heinonen (2021) measured the value of social media marketing from a destination marketing organization point of view while Kaefer (2021) discussed the views Jaume Marín, a tourism expert on destination branding and social media during the time of COVID-19. Solazzo, Maruccia, Lorenzo, Ndou, Del Vecchio and Elia (2021) explored analysis from big data on smart tourism destination management also during the period of COVID-19.

METHOD

Destination marketing, technology in tourism and COVID-19 content was taken from resources that include publicly accessible reports, research published databases that include Scopus, IBSS, DOAJ and were retrieved through search engines such as Google Scholar as well as university rese-

arch repositories. The sources utilised for purposes of this research were carefully screened for relevance, currency and suitability. It was not possible to exhaust every possible aspect relevant to destination marketing but comprehensive literature review made every possible attempt to cover the key issues pertaining to the topic. Keywords and phrases, which include, “Destination marketing”, “Technology in Tourism” and “COVID-19” were utilised in retrieving academic articles. This was to identify common themes and trends.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The findings of this research are based on the studies reviewed for purposes of this research. Themes emerging from the findings are discussed. A total of four themes were identified from the investigation, namely; destination marketing, technology in tourism, COVID-19 impact on tourism and destination image. Results were based on secondary publicly available sources which included relevant literature and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNTWO) data.

Theme 1: Destination Marketing

First, it was established that by its

very nature destination marketing is a very difficult process to manage (Buhalis, 2000; Sautter & Leisen, 1999). This assertion is in line with the main idea of the present research which explored the difficulty of marketing destinations. According to UNTWO (2020), domestic tourism is the main reason for COVID-19 recovery of most destinations but in most cases this is only partial, as it is not compensating for the decrease in international tourism demand. Due to limitations on travel, a trend was created whereby tourists started to post past trips on travel websites as they yearned to travel again (Gretzel et al., 2020).

Furthermore, these travel bans, motivated the increased use of virtual museums that kept destinations competitive (Gretzel et al., 2020).

Theme 2: Technology in Tourism

Technology has become actively adopted in tourism over the years. A second theme that emerged from the study was the increased use of technology in tourism. This became apparent with the outbreak and spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Etourism and the internet enable interactivity between tourism enterprises and their customers (Buhalis & O’Connor, 2005). Due to traditional offline activities being limited

Table 1. Destination Marketing, Tourism Technology & COVID-19 Tourism Literature

Theme Author(s)

Destination Buhalis (2000), Fyall and Leask (2006), Gretzel, Fesenmaier, Formica Marketing and O’Leary (2006), Hays, Page and Buhalis (2013), King, (2002),

Lange-Faria and Elliot (2012), Pike (2012) and Wang and Xiang (2007).

Technology Buhalis and O’Connor (2005), Buhalis and Law (2008), Ukpabi and in tourism Karjaluoto (2017), Huang, Backman, Backman and Chang (2016) and

Werthner and Klein (1999).

COVID-19 Altuntas and Gok (2021), Foo et al. (2020), Fotiadis et al. (2021), impact on Gretzel et al. (2020), Kaushal and Srivastava (2021), Piguillem and Shı,

Tourism 2020, Qiu et al. (2020) Sigala (2020) and Yu et al. (2020)

Destination Afshardoost and Eshaghi (2020), Baloglu and McCleary (1999), Beerli Image and Martin (2004), Echtner and Ritchie (1993), Pike (2002) and Stylidis (2020), Tasci and Gartner (2007).

as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital marketing, especially social media, became the main promoter of Indonesian tourism (Chloridiany, 2021).

Theme 3: COVID-19 impact on Tourism

The third theme that emerged from the research was concerned with the impact of COVID-19 on tourism. Globally, nations imposed quarantines as they were believed to be the most effective approach to reducing the impact of COVID-19 (Altuntas & Gok, 2021). However, Altuntas and Gok (2021) added that these quarantines negatively affected the hospitality industry as it relies solely on customers. The airline industry and the hotel industry were server-ly impacted my COVID-19 at its peak in 2019/20 in regions such as Malaysia which relies on Singapore and China (Loo et al., 2020). The Chinese government shut-down the country completely for foreign tourists on 29 March 2020 in addition to restrictions that had already been imposed on foreign airlines that included not exceeding 75% capacity and one flight per week (Loo et al., 2020).

Theme 4: Destination Image

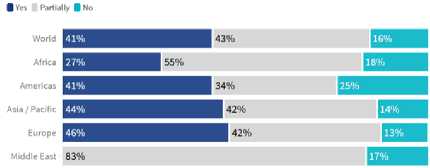

The last theme identified was destination image. This emerged from numerous studies reviewed for this research. As far as destination image is concerned, some research, Afshardoost and Eshaghi (2020) found links between destination image and intention to visit and revisit. The study under investigation also established that there was a decrease in visits to other countries during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. This could have been due to the image of destinations perceived by travellers as a result of the global pandemic. This is supported by the UNTWO (2021) which predicted a reduction of international tourism by 70% as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 1 below shows results

from tourism experts’ perceptions on the extent to which they felt domestic tourism contributed to destinations’ recovery from COVID-19. These results are based on a global survey conducted by the UNTWO on the impact of COVID-19 on tourism and the expected time of recovery.

Source: Adapted from UNTWO (2021) Figure 1. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism and the expected time of recovery

Figure 1 shows the results from tourism experts’ perceptions on the extent to which they felt domestic tourism contributed to destination’s recovery from COVID-19. Tourism experts from Europe were the most positive regarding the contribution of domestic tourism to the recovery of destinations. The least positive group of tourism experts were from Africa. Almost 75% of this group believed that there would either be a partial tourism recovery or no recovery at all. Tourism experts from the Middle East were very sceptical about the regions recovery from tourism as none of them could state with certainty that there would be recovery from COVID-19. However, 83% of Middle Eastern tourism experts did partially believe that recovery from tourism was possible for their region while 17% believed they would be no recovery from COVID-19. The following section presents the study’s conclusions.

CONCLUSION

This research focused on assessing the effectiveness of technology in destination marketing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. A number of themes emerged from

the investigation which included, destination marketing, technology in tourism, COVID-19 impact on Tourism and destination image. Technology was visibly effective in keeping destinations relevant and competitive, especially through the use of social media as physical tourist activities were limited due to the pandemic. The research explored extent to which technology was utilised in destination marketing during the first recorded year of the COVID-19 pandemic’s global spread. The results of the assessment of technology revealed that E-tourism played a key role in filling the gap left by destination closures and restrictions to travel which motivated the increased use of virtual museums (Gretzel et al., 2020). Furthermore, tourists made an effort to share past travel memories on social media and in general remained active on travel websites dreaming about their future holidays (Gretzel et al., 2020). It was therefore established that technology adoption in tourism was widely accepted but still presented challenges its fair share of challenges to the user. Furthermore, it should also be noted that, as much as there is an abundance of literature on COVID-19 in various fields including tourism research, it still remains to be further discussed as new knowledge continues to emerge. This is because the pandemic is novel thus required continued exploration. The following section outlines the limitations of the present study and proposes future research direction.

REFERENCES

Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analy-sis. Tourism Management, 81, 1-20.

Akehurst, G. (2009). User generated content: the use of blogs for tourism organisations and tourism consumers.

Service Business, 3(1), 51-61.

Altuntas, F., & Gok, M. S. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic tourism: A DEMATEL method analysis on quarantine decisions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 1-9.

An, S., Choi, Y., & Lee, C. K. (2021). Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 1-10.

Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of tourism research, 26(4), 868-897.

Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of tourism research, 31(3), 657-681.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism management, 21(1), 97-116.

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet - The state of eTourism research. Tourism management, 29(4), 609-623.

Buhalis, D., & O’Connor, P. (2005). Information communication technology revolutionizing tourism. Tourism recreation research, 30(3), 7-16.

Cheng, M., & Edwards, D. (2015). Social media in tourism: a visual analytic approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(11), 1080-1087.

Chloridiany, A. (2021). Social Media Marketing Strategy of Indonesian Tourism in the Time of Pandemic. E-Journal of Tourism, 8 (1), 1-13.

Chuchu, T., Chiliya, N., & Chinomona, R. (2018). The impact of services cape and traveller perceived value on affective destination image: an airport retail services case. The Retail and Marketing Review, 14(1), 45-57.

Chuchu, T. (2020). The Impact of Airport Experience on International Tourists’ Revisit Intention: A South African Case. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 29(2), 414-427.

Chen, C. C., & Tsai, J. L. (2019). Determinants of behavioral intention to use the Personalized Location-based Mobile Tourism Application: An empirical study by integrating TAM with ISSM. Future Generation Computer Systems, 96, 628-638.

Davis, F.D. (1989). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Systems Characteristics, User Perceptions and Behavioural Impacts. International Journal of Man Machine Studies, 38, 475-487.

Dulcic, Z., Pavlic, D., & Silic, I. (2012). Evaluating the intended use of Decision Support System (DSS) by applying Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in business organizations in Croatia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, 1565-1575.

Echtner, C. M., & Ritchie, J. B. (1993). The measurement of destination image: An empirical assessment. Journal of travel research, 31(4), 3-13.

El-Gohary, H. (2012). Factors affecting E-Marketing adoption and implementation in tourism firms: An empirical investigation of Egyptian small tourism organisations. Tourism management, 33(5), 1256-1269.

Foo, L. P., Chin, M. Y., Tan, K. L., & Phuah, K. T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Cur-

rent Issues in Tourism, 1-5.

Fotiadis, A., Polyzos, S., & Huan, T. C. T. (2021). The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 1-14.

Fyall, A., & Leask, A. (2006). Destination marketing: Future issues—Strategic challenges. Tourism and hospitality research, 7(1), 50-63.

Gretzel, U., Fesenmaier, D. R., Formica, S., & O’Leary, J. T. (2006). Searching for the future: Challenges faced by destination marketing organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 116-126.

Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., Baggio, R., Ho-epken, W., Law, R., Neidhardt, J., Pesonen, J., Zanker, M., & Xiang, Z. (2020). e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: a call for transformative research. Information Technology & Tourism, 22, 187-203.

Gumpo, C.I.V., Chuchu, T., Maziriri, E.T., & Madinga, N.W. (2020). Examining the usage of Instagram as a source of Information for young consumers when determining tourist destinations. South African Journal of Information Management, 22 (1), 1-11.

Hanan, H. & Putit, N. (2014). Express marketing of tourism destination using Instagram in social media networking. In Norzuwana Sumarjan, Mohd Salehu-din Mohd Zahari, Salled Mohd Radzi, Zurinawati Mohi, Mohd Hafiz Mohd hanafiah, Mohd Faeez Saiful Bakhtiar & Atinah Zainal (Eds.), Hospitality and Tourism: Synergizing creativity and innovation in research (pp. 471474). Croydon, Great Britain: Taylor & Francis Group.

Hays, S., Page, S. J., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: its use by national tourism organisations. Current issues in Tour-

ism, 16(3), 211-239.

Herrero, Á., & San Martín, H. (2012). Developing and testing a global model to explain the adoption of websites by users in rural tourism accommodations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1178-1186.

Hospers, G. J. (2004). Place marketing in Europe. Intereconomics, 39(5), 271279.

Huang, Y. C., Backman, K. F., Backman, S. J., & Chang, L. L. (2016). Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: An integrated research framework. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 116-128.

Hudson, S., & Thal, K. (2013). The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: Implications for tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 156-160.

Hvass, K. A. (2014). To fund or not to fund: A critical look at funding destination marketing campaigns. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(3), 173-179.

Ibrahim, R., Leng, N. S., Yusoff, R. C. M., Samy, G. N., Masrom, S., & Rizman, Z. I. (2017). E-learning acceptance based on technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, 9(4S), 871-889.

Li, C. & Bernoff J. (2008). Groundswell: Winning in a World Transformed by Social Technologies. New York, Harvard Business Press.

Rauniar, R., Rawski, G., Yang, J., & Johnson, B. (2014). Technology acceptance model (TAM) and social media usage: an empirical study on Facebook. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 27(1), 6-30.

Sharmin, F., Sultan, M. T., Badulescu, D., Badulescu, A., Borma, A., & Li, B. (2021). Sustainable destination marketing ecosystem through smartphonebased social media: The consumers’ acceptance perspective. Sustainability, 13(4), 1-24.

Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of business research, 117, 312-321.

Solazzo, G., Maruccia, Y., Lorenzo, G., Ndou, V., Del Vecchio, P., & Elia, G. (2021). Extracting insights from big social data for smarter tourism destination management. Measuring Business Excellence. Emerald.

Kaefer, F. (2021). Jaume Marín on Destination Branding and Social Media. Management for Professionals, 173-175.

Kaushal, V., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102707.

King, J. (2002). Destination marketing or-ganisations-Connecting the experience rather than promoting the place. Journal of vacation marketing, 8(2), 105108.

Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., Josiassen, A., Assaf, A. G., & Tsionas, M. G. (2020). Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Annals of tourism research, 85, 1-13.

Kumpu, J., Pesonen, J., & Heinonen, J. (2021). Measuring the Value of Social Media Marketing from a Destination Marketing Organization Perspective. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021 (pp.

365-377). Springer, Cham.

Kurashima, T., Iwata, T., Irie, G., & Fujimura, K. (2010). Travel route recommendation using geotags in photo sharing sites. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM international conference on Information and knowledge management (pp. 579-588).

Lange-Faria, W., & Elliot, S. (2012). Understanding the role of social media in destination marketing. Tourismos, 7(1), 193-211.

Lee, Y., Kozar, K. A., & Larsen, K. R. (2003). The technology acceptance model: Past, present, and future. Communications of the Association for information systems, 12(1), 752-780.

Leung, D., Law, R., Van Hoof, H., & Bu-halis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of travel & tourism marketing, 30(1-2), 3-22.

Li, S. C., Robinson, P., & Oriade, A. (2017). Destination marketing: The use of technology since the millennium. Journal of destination marketing & management, 6(2), 95-102.

MarketResearch.com (2021). Impact on Travel and Tourism Social Media -COVID-19 – Thematic Research. Retrieved from https://www.marke-tresearch.com/GlobalData-v3648/ Impact-Travel-Tourism-Social-Me-dia-13391987/ Accessed 17/06/2021

Miguéns, J., Baggio, R., & Costa, C. (2008). Social media and tourism destinations: TripAdvisor case study. Advances in tourism research, 26(28), 1-6.

Milano, R., Baggio, R., & Piattelli, R. (2011). The effects of online social media on tourism websites. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2011 (pp. 471-483).

Springer, Vienna.

Miličević, K., Mihalič, T., & Sever, I. (2017). An investigation of the relationship between destination branding and destination competitiveness. Journal of travel & tourism marketing, 34(2), 209-221.

Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2012). Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 36-46.

Noor, N. L., Hashim, M., Haron, H., & Ariffin, S. (2005). Community acceptance of knowledge sharing system in the travel and tourism websites: an application of an extension of TAM. 13th European Conference on Information Systems, Information Systems in a Rapidly Changing Economy.

Okumus, B., Okumus, F., & McKercher, B. (2007). Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tourism management, 28(1), 253-261.

Palmer, A., & Bejou, D. (1995). Tourism destination marketing alliances. Annals of tourism research, 22(3), 616629.

Phatthana, W., & Mat, N. K. N. (2011). The Application of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) on health tourism e-purchase intention predictors in Thailand. In 2010 International Conference on Business and Economics Research (Vol. 1, pp. 196-199).

Piguillem, F., & Shi, L. (2020). Optimal Covid-19 Quarantine and Testing Policies. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14613.

Pike, S. (2002). Destination image analy-sis-a review of 142 papers from 1973

to 2000. Tourism management, 23(5), 541-549.

Pike, S. (2012). Destination marketing. Routledge.

Pollock, A. (1995). The impact of information technology on destination marketing. Travel & Tourism Analyst, 3, 6683.

Sautter, E. T., & Leisen, B. (1999). Managing stakeholders: A tourism planning model. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 312-328.

Sonnleitner, K. (2011). Destination image and its effects on marketing and branding a tourist destination: A case study about the Austrian National Tourist Of-fice-with a focus on the arket Sweden. Master’s Dissertation. Retrieved from http://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/ diva2:424606/FULLTEXT01.pdf Accessed (17/06/ 2021)

Stylidis, D. (2020). Residents’ destination image: a perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 228-231.

Tasci, A. D., & Gartner, W. C. (2007). Destination image and its functional relationships. Journal of travel research, 45(4), 413-425.

Torres, R. (2010). Today’s traveler online: 5 consumer trends to guide your marketing strategy. Paper presented at the Eye for Travel, Travel Distribution Summit, Chicago, IL.

Ukpabi, D. C., & Karjaluoto, H. (2017). Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 618-644.

UNWTO (2011). Policy and Practice for Global Tourism. Madrid: UNWTO.

UNTWO (2021). Impact Assessment of the Covid-19 Outbreak on Internation-

al Tourism. Retrieved from: https:// www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-interna-tional-tourism Accessed 18/09/2021

Usoro, A., Shoyelu, S., & Kuofie, M. (2010). Task-technology fit and technology acceptance models applicability to e-tourism. Journal of Economic Development, Management, IT, Finance, and Marketing, 2(1), 1-32.

Wang, Y., & Pizam, A. (Eds.). (2011). Destination marketing and management: Theories and applications. Nosworthy Way, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK. Cabi.

Wang, Y., & Xiang, Z. (2007). Toward a theoretical framework of collaborative destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 75-85.

Weber, L. (2009). Marketing to the social web: How digital customer communities build your business. John Wiley & Sons.

Weinberg, T. (2009). The new community rules: Marketing on the social web (pp. I-XVIII). Sebastopol, CA: O›Reilly.

Werthner, H., & Klein, S. (1999). Information technology and tourism: a challenging relationship. Springer-Verlag Wien.

Yavuz, S.S., & Ünal, S. (2020). Antiviral treatment of COVID-19. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 50, 611-619.

Ye, Q., Law, R., Gu, B., & Chen, W. (2011). The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Computers in Human behavior, 27(2), 634-639.

Yu, M., Li, Z., Yu, Z., He, J., & Zhou, J. (2020). Communication related health

crisis on social media: a case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current issues in tourism, 1-7.

Yu, C. E., Xie, S. Y., & Wen, J. (2020). Coloring the destination: The role of color psychology on Instagram. Tourism Management, 80, 104110.

Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tour-

ism? A review. Tourism management perspectives, 10, 27-36.

Zhang, J., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Tseng, C., & Chen, Y. C. (2018). How country image affects tourists’ destination evaluations: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(6), 904-930.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

160

e-ISSN 2407-392X. p-ISSN 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback