Conceptual Model for Mutual (Host-Guest) Authentication of Intangible Cultural Heritage

on

E-Journal of Tourism Vol.6. No.2. (2019): 160-177

Conceptual Model for Mutual (Host-Guest) Authentication of Intangible Cultural Heritage

Shahida Khanom1, Noel Scott1, Millicent Kennelly2, and Brent Moyle3

-

1 Griffith Institute of Tourism, Griffith University, QLD, Australia

-

2 Department of Tourism, Sport and Hotel Management, Griffith University, QLD, Australia 3

-

3 Faculty of Arts, Business and Law, University of the Sunshine Coast, QLD, Australia

Corresponding author: shahida.khanom@griffithuni.edu.au

|

ARTICLE INFO |

ABSTRACT |

|

Received 30 March 2018 |

The intangible cultural heritage (ICH) of indigenous communities is an attraction to many tourists. Authentic ICH experiences rely on the |

|

Accepted 02 September 2019 Available online 30 September 2019 |

perceptions and actions of both the host community and guests, a topic which has received with limited scholarly attention, particularly in recent research. This paper presents a conceptual model examining how the mutual (host-guest) authentication of ICH (integrating the perceptions of both hosts and guests) can potentially lead to community empowerment. A literature review has identified that the host community’s attitude and motivation towards ICH, their psychological and economic benefit from ICH, and their participation or involvement in the ICH, together influence the authentication of ICH by these communities. Similarly, a guest’s attitude to and motivation for ICH as well as the way the traditional objects, events or environment are experienced, influence the authentication of ICH. The proposed mutual ICH authentication model combines the interaction of such host and guest factors in authentication of ICH, i.e. both the host community and guest should perceive the same elements as authentic ICH through a synthesis of their own unique perspectives. The perceived authenticity of ICH by the host and guest is reflected in their loyalty, satisfaction, and support for tourism. Further, the model suggests that tourism based on authentic ICH has the potential to empower local communities in their economic, social, psychological and political domains. The proposed model may be useful for future research defining power relations in the authentication of ICH and improving community-based ecotourism through community empowerment. Keywords: intangible cultural heritage, authenticity, mutual authentication, cultural tourism, community empowerment |

INTRODUCTION

Background

Cultural tourism, a growing sector of the global tourism industry, includes experiencing the authentic culture of indigenous communities, especially the traditional practices, rituals, festivals and lifestyle which form their intangible cultural heritage (ICH) (Cohen, 1988; Moswete &Thapa, 2015; UNESCO, 2011). Historically significant ICH such as festivals and religious events attract many tourists. For instance, the Mekong Naga Fireball ceremony in Thailand (Cohen, 2007), Holy Week on the island of Sardinia (Giudici et al., 2013), and the Rush Mela festival in Bangladesh (Islam et al., 2018) all draw a large number of tourists every year. These centuries-old traditional festivals are associated with the religious beliefs of the local community and have a significant impact on the society, economy and cultural development of the region. These ICH events or experiences have become major tourist attractions, providing not only additional economic benefits to the local community but also revenue to the government (Moswete & Thapa, 2015; UNESCO, 2011). However, the growing trend of cultural tourism in developing countries has raised concerns about unsustainable tourism practices and the http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot 161

commodification of ICH (Fiorello & Bo, 2012; Zhou et al., 2015). The commodification process potentially destroys the essential meaning and significance of the ICH to the local community and diminishes its authenticity (Zhou et al., 2015).

The authenticity of ICH remains a critical issue in cultural tourism, as the ICH’s ownership is being contested in the face of commodification by its commercialization. Clearly defining the authenticity of ICH, an authentication process embedded in ICH’s relation to community empowerment would help to preserve ICH and reduce its commodification. Generally, a host community creates, maintains and transmits ICH over generations (UNESCO, 2011) and is, therefore, the primary stakeholder in its authentication. However, guests’ perceptions and the role of institutions in such authentication are also vital for preserving ICH and developing tourism (Cohen & Cohen, 2012; Mkono, 2013).

The recent literature discusses several models for the authentication of ICH from either the host’s (Zhou et al., 2015) or the guest’s perspectives (Cho, 2012; Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013). These models present a partial view of the authenticity of ICH, ignoring the

importance of simultaneously taking into account both the host’s and the guest’s perception for the authentication process. There is little discussion of the mutual (host-guest) authentication of ICH and its relation to community empowerment, although community empowerment is considered essential for safeguarding ICH (Alexander, 2009; Cole, 2007).

Research Objectives

This paper presents a critical review of the existing models of authenticating ICH and proposes a conceptual model for mutual (host-guest) authentication of ICH (integrating host and guest’s perceptions) that can potentially lead to community empowerment. The proposed model would help to understand the relation between the mutual authentication of ICH and community empowerment, which could offer support for preventing the commodification of ICH and for enhancing the local community’s role in ICH-based tourism.

METHODOLOGY

A review of literature was conducted to examine extant knowledge on four related key areas: the authenticity of ICH, existing models for the authentication of ICH from host or guest

perspectives, the factors influencing the authenticity of ICH and ICH’s relation to community empowerment. The review began with a keyword-based search (Loulanski & Loulanski, 2011) in Google Scholar, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Sage databases using the terms: authenticity, intangible cultural heritage, ICH tourism, host(s) and guest(s), authenticity model, and community empowerment. From the initial pool of about 200 relevant articles, 50 articles were identified as most relevant to the topic of this research. An in-depth manual review of these articles was carried out, focusing on the existing models of authenticating ICH from host and guest perspectives, factors influencing the authenticity of ICH and its linkage with tourism and community empowerment.

Review of existing authentication models

The authenticity of traditional objects and cultural practices has been crucial for providing an authentic experience in cultural tourism. In early decades of 19th century, the authenticity of objects, which was conceptualized as objective authenticity – meaning the originality of the objects and that these have significance to the society from a historical point of view (Trilling, 1972;

Wang, 1999) – were considered important for cultural tourism. In the second half of the 20th century, with the advent of easily accessible destinations through mass transportation by air, tourism to cultures different from the guests’ own culture grew exponentially. Unsurprisingly, therefore, in the 1970s, the intangible cultural heritage of traditional communities (e.g. cultural practices, festivals) has attracted scholarly attention as issues surrounding the commodification of culture were identified to have the potential to destroy the meaning of the local ICH and inadvertently detract from the tourist experience (Greenwood, 1977). During the 1990s, researchers shifted focus to the existence of authentic ICH, which was conceptualized as existential authenticity, and its verification, acknowledging the need to preserve the value of traditional ICH (Casey, 1993).

Various authentication processes have been theorized in the literature to define the authenticity of objects and traditional cultural practices. A “cool” authentication process is associated with an external expert’s (or institution’s) power to authenticate an object or event. Such an authentication process mainly focuses on the tourists’ quest for authenticity. Whereas, a “hot” authentication process relies on the host community’s beliefs about the authenticity http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

of the festival or practice in which they engage, rather than on any scientific evidence of authenticity or on authentication by an expert outside the community (Cohen & Cohen, 2012). Traditional ICH experiences (e.g. festivals) demonstrate hot authenticity, as the community authenticates it by having participated in and practiced it over generations. The tourists (or guests) participating in tourism related to those ICH events can have an authentic experience of the community’s ICH. As such, the guests participate in the hot authentication process through the interaction between the hosts and guests in ICH tourism.

While ICH tourism leads to a close interaction of this type, the recent development of both hot and cool authentication processes fails to

adequately incorporate the interaction between host and guest in the authentication process, which raises the issue of a mutual authentication process for ICH (Cohen & Cohen, 2012). Moreover, as the community directly interacts with the guests, host-guest power relations are important for the hot authentication of ICH. Hot authentication allows guests to have an empathic understanding of the rights of hosts in their traditional ICH. This understanding develops trust between the host and guest 163 e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

and such trust also increases the empowerment of the community (Gnotha & Wang, 2015). Hosts also should understand that tourists from another society want an authentic experience of traditional objects and culture (Cho, 2012). As such, mutual interaction between the host and guest is necessary for the hot authentication of ICH. This can satisfy the tourist as well as empower the community.

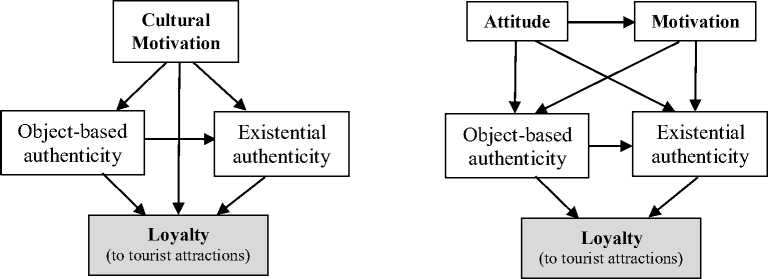

In the quest of theorizing the authentication process, several quite distinct authentication models have been developed. What unites them is that they have all been based either on hosts’ or on guests’ perceptions of authenticity (Cho, 2012; Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013). Kolar and Zabkar (2010) proposed a consumer-based model of authentication (Figure 1) which suggested that the cultural motivation of the tourists was an important factor for both object-based and existential authenticity. Such cultural motivation influenced tourist loyalty to

tourist attractions. Further development of the Kolar and Zabkar (2010) model by Zhou et al. (2013) (Figure 2) suggested that the ‘attitude’ of the tourist should be included in the authentication process along with the ‘motivation’ factor. Interestingly. Zhou et al. (2013) found that this attitude, conceptualized as individual beliefs, interests, and understanding of tourism activities, has no effect on the motivation for visiting the ICH attractions and does not influence loyalty directly. These researchers also emphasized that the tourism industry’s ignorance of traditional culture led the tourists to give importance to the aesthetics and form of the cultural objects or materials, rather than focusing on the experience of traditional culture. An alternative conceptual model of authenticity was developed by Cho (2012) to examine the relationship between tourists’ motivation, their perceptions of authenticity and their satisfaction. The model suggests that tourists’ motivation

Figure 2: Modified consumer-based authenticity model (Zhou et al., 2013)

Figure 1: Consumer-based authenticity model (Kolar & Zabkar, 2010)

affects both objective and existential authenticity, which, in turn, both influence tourist satisfaction (Cho, 2012). While Kolar and Zabkar’s (2010) and Cho’s (2012) models found that both forms of authenticity were related to motivation, Zhou et al. (2013) argued that motivation has an insignificant effect on existential authenticity.

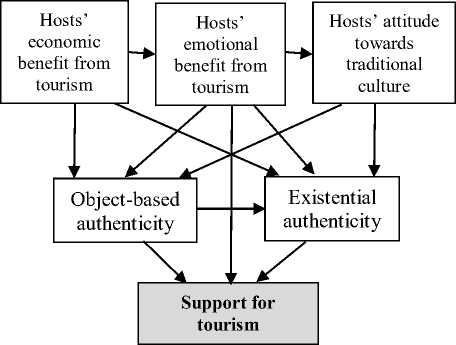

In addition to the consumer-based (tourists’) authentication model, a few recent studies have focused on the authentication of tourist attractions by the host community. For example, Zhou et al. (2015) found that the hosts’ attitude towards traditional cultural practices, together with their personal emotional and economic benefits from cultural tourism influence the process of host authentication as these factors affect both objective and existential authenticity. The hosts’ attitude is directly influenced by the personal emotional benefits, whereas the personal economic benefits are indirect and hidden from any obvious position in the hosts’ support of tourism. As such, the hosts’ personal emotional benefits from practicing and sharing the culture with the guest through tourism enhance the cohesion and identity of the hosts’ culture, which leads to a psychological empowerment of the host community. The economic benefits to the hosts from tourism lead to an economic http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

empowerment of the community (Zhou et al., 2015). A similar observation was made by Boley et al. (2014) who concluded that personal economic benefits and psychological empowerment have direct and positive effects on the hosts’ support for tourism. However, both Boley et al. (2014) and Zhou et al. (2015) did not consider the social and political dimensions of community empowerment in relation to ICH’s objective and existential authenticity as well as the implications of these dimensions for the hosts’ support for tourism.

The above-discussed authentication models have mainly focused on tourists’ behavior and partially on community empowerment (in terms of psychological and economic empowerment, two of the four identified dimensions of community empowerment (Di Castri, 2004; Scheyvens, 1999)) to verify the authenticity of cultural experiences according to the views of either hosts or guests (Cho, 2012; Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015). However, these studies are limited by the use of quantitative approaches with structural equation modeling used to assess authenticity. This quantitative modeling approach is helpful for examining relationships between variables. However, perhaps, each concept embedded within these models should be

investigated thoroughly using inductive qualitative methods (Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015).

Further, the current models of ICH authentication consider the guest (tourist) and host (community) perspectives separately, which can provide only a partial view. These ICH authentication processes do not directly take into account the linkages between the host and guest, nor the understandings common to both groups and the connection of this to community empowerment. A lack of adequate interaction between hosts and tourists can lessen the authentic experience for the tourist as well as curb benefits to

Figure 3: Host authenticity model (Zhou et al., 2015)

the host community and impact host empowerment (Cho, 2012; Zhou et al., 2015).

Therefore, direct interaction between hosts and guests can improve the mutual authentication of tourist attractions as well as develop trust between hosts and

guests in order to enhance host empowerment (Moyle et al., 2010; Zhu, 2012). For ICH authentication, a mutual (host-guest) authentication model would be necessary to examine the linkages between host and guest and their influence on community empowerment.

Conceptual model for mutual (hostguest) authentication of ICH

Overview of the mutual (host-guest) authentication model

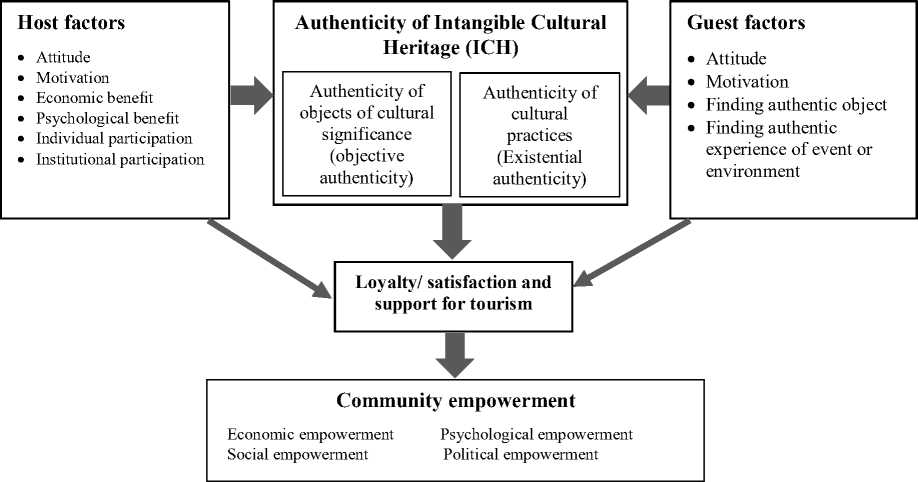

Considering the limitations of the current authentication models, a new model is conceptualized for the mutual (host-guest) authentication of ICH which incorporates both hosts’ and guests’ perspectives of authenticity (Fig. 4). This model also shows the linkage of authentication to satisfaction, loyalty and support for tourism development as well as the linkage to enhance community empowerment. The model takes into account both objective and existential authenticity. Objective authenticity is covered by the authentication of the objects that are culturally significant to the community such as architectural structures, artifacts or similar physical elements used for performing cultural practices. The physical objects used in performing the cultural events or in the daily lifestyle of the community are the

elements that determine the objective authenticity of the community’s ICH (Asplet & Cooper, 2000). The existential authenticity of ICH is covered by the authentication of the existence of cultural traditional practices such as festivals and religious rituals performed by the community. The traditional cultural practices, religious and social customs, and the way the community perform the events which define its community’s unique identity, together determine the existential authenticity of the ICH (Zhou et al., 2015). Perceptions of both the hosts (i.e., the local community) and the guests (i.e., tourists) would be considered for the mutual authentication of ICH.

This model comprises several factors related to the perceptions of hosts and guests that can influence ICH authenticity. The hosts’ factors include

their attitude and motivation towards ICH, economic and psychological benefits, and participation in cultural practices, individually and through institutions. The guests’ factors include their attitude towards ICH, motivation to experience ICH, and finding authentic objects or experiences of events. The mutual (hostguest) authentication of ICH would ultimately reinforce the loyalty, satisfaction and support for ICH tourism as well as enhancing community empowerment. The host and guest factors influencing the authenticity of ICH and linkages to tourism development and community empowerment are further illustrated in the following sections.

Figure 4: A model for mutual (host-guest) authentication of ICH

Host community factors influencing the authenticity of ICH

Hosts’ attitude: Attitudes are important for explaining and predicting perceptions and behavior. Generally, attitudes are a type of social knowledge consisting of experiences, beliefs, and feelings (Zanna and Rempel, 2008). As an enduring predisposition towards a particular aspect of one’s environment, attitudes consist of either a two or three component response to an object or event: cognitive (beliefs, knowledge, perceptions); affective (likes and dislikes); and behavioral (the instinct to act) (Subramaniam and Silverman, 2007). One’s attitude can be inferred directly from one’s behavior; living a traditional lifestyle indicates the attitude of a willingness to do so. In the context of this authentication model, such an attitude comprises one’s level of understanding of traditional culture and the degree of preference for it.

Hosts’ attitudes towards traditional culture include their emotion, cognition, and behavior concerning traditional life, the local religion, and modern civilization. Hosts’ attitude towards traditional culture plays a role in the ICH authentication process because their attitude to the objects of cultural significance and to the http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

traditional cultural practices reflects how they define both the objective and existential authenticity of ICH. Earlier models of host authentication (e.g. Zhou et al., 2015) did not explicitly include the host’s attitude as a variable, whereas authenticity models based on tourist perceptions (e.g. Kolar & Zabkar, 2010) include tourists’ attitude as one of the prime factors.

In the proposed mutual authentication model, we consider the hosts’ attitude to their ICH should be an essential determinant of the authenticity of this instance of ICH, and we compare this with the guests’ attitude to the same ICH phenomena. Hosts’ attitude to the ICH could be measured by ascertaining their belief and willingness to carry forward the traditional ICH elements to future generations. Thus, hosts’ positive attitude would show their feeling towards traditional ownership of the ICH and reflect its authenticity.

Hosts’ motivation: Hosts’

motivation to practice traditional culture is important to determine their perception of ICH. Hosts’ motivation for ICH can be classified into two categories: general motivation and intentional motivation. The general motivation of the host community to perform their cultural practices could be to follow the tradition of the community 168 e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

they live in (Yoon & Uysal, 2005). The intentional motivation of the host’s community could be linked to religious belief, economic benefit, and sociopolitical benefits from practicing the cultural traditions (McIntosh & Prentice, 1999). For instance, hosts can be motivated to participate in a traditional festival to perform religious rituals. The motivation of some hosts may be to sell products at the festival. Therefore, the motivation of the hosts’ community is an important determinant of the authenticity of ICH from the hosts’ perspective. A strong positive motivation of the host community would tend to reflect a strong perception of the ICH’s authenticity. Although earlier consumer-based authenticity models (e.g. Kolar & Zabkar, 2010) considered the motivation of the guests as a crucial factor influencing ICH authenticity, host-based authenticity models (e.g. Zhou et al., 2015) have not included the hosts’ motivation as a factor in authentication. The hosts’ motivation is included as a factor in the mutual authentication model to reflect the influence of the hosts’ motivation as being as valuable as the guests’ motivation.

Hosts’ economic benefit from ICH: Hosts’ economic activities related to traditional ICH events festivals may include selling handicrafts, foods, and http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

other –tourism experiences which provide economic benefits to them. Traditional cultural events or festivals organized regularly for many years can give seasonal livelihood opportunities to some group or groups within the host community. Regular economic activities surrounding the ICH can increase hosts’ attachment to the ICH event and to ICH itself. Zhou et al. (2015) found that economic benefit does not directly affect the objective and existential authenticity while emotional benefit does. Economic benefits from ICH affect hosts’ attitude and emotional benefits; therefore, economic benefits indirectly affect both objective and existential authenticity. When hosts are dissatisfied with the economic benefits of an ICH experience, they vent with negative emotions and evaluate its authenticity by belittling it. By contrast, their positive moods and emotions lead to overestimating authenticity to be higher than the objective level. Although sometimes hosts do not explicitly express it, they are very concerned about the promotion of local culture for local economic development and to increase their income (Chhabra, 2010). To some extent, to escape poverty or become wealthy, they unconsciously accept a certain degree of sacrifice of the authenticity of local culture. It is unrealistic to talk about protecting and

inheriting tradition if economic benefits cannot be guaranteed (Yang et al., 2013). In view of the above contexts, hosts’ economic benefit from ICH is taken into account in the mutual ICH authentication model.

Psychological benefit: The host community can have psychological or emotional benefit by performing traditional cultural expressions (Besculides et al., 2002). For example, hosts can have mental peace and satisfaction by engaging in rituals in a traditional religious festival or meeting friends and families at the cultural event or enjoying the cultural programmes. They can also feel proud or satisfied by showcasing their traditional culture to tourists (Besculides et al., 2002). Cole (2007) found that locals are proud that their villages are considered part of the national heritage and that they like tourists because tourism provides entertainment, friends from the outside world and outside information. ICH-based tourism brings the villagers confidence and dignity in their beliefs. Thus, personal emotional benefit is the crucial factor for the authentication of ICH by the hosts.

Individual participation: The

individual participation of a host in traditional cultural practices shows his/ her devotion to being attached to their own http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot 170

community and culture. According to Teodori and Luloff (1998), community involvement, including support for a festival, is an important factor in predicting the strength of a person’s attachment to a community or place. Studies have shown that recognizing people’s attachment to a place influences their sense of stewardship and perception of authenticity in a destination (Greene, 1996). Individuals’ affective relationship with the landscape or material environment may express their perception of the existential authenticity of ICH (Tuan, 1974). An emotional attachment to the natural landscape and the built environment and shared memories of communal heritage allow individuals to come together for formal or spontaneous interactions like festivals and community and cultural events. The individual perception of authenticity ensures the collective identity of the ICH. Therefore, hosts’ individual participation in practicing their ICH is taken as an important factor that influences its authenticity.

Institutional participation: ICH can act as the heart of a community (Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers, 1998, p.14) as its intrinsic nature provides residents with conditions of freedom and connectedness rather than a fixation on the community’s forms and structure.

Community institutions managing the ICH can provide a sense of its importance to the community. A formal community organization structure based on the common interest of the community provides an opportunity to nurture traditional culture over generations and preserve it for the future. The community institutions can even promote the cultural events to the larger society, involving political power and recognition by the state (del Barrio, Devesa and Herrero, 2012). Hosts’ participation in the community institutions for managing ICH would show how the host recognizes the ICH’s value of and how the host perceives the authenticity of this ICH. Thus, this host factor is included in the mutual authentication model.

Guest/ tourist factors influencing the authenticity of ICH

Guests’ attitude: The guests’ attitude towards the traditional culture, expressed by authentic objects or the existence of genuine cultural events, can contribute to the authenticity of the ICH. Attitude is generally evaluated on the long-term activities including cognitive, affective and behavioral responses. Attitudes predispose a person to act or perform in a certain manner based on his/ her cognitive and affective evaluation

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot 171

while engaging in ICH activities. Thus, the attitude to ICH is particularly demonstrated by the degree of attention to particular objects or experiences and a deeper level of understanding of the ICH, including the historical and cultural background. Tourists are influenced by their emotions which stimulate their perception through interaction with the host. This is particularly evident in the case of a festival when the tourist perceives high existential authenticity, for example in a worshipping ceremony. When a tourist feels affection for the host community they feel more enthusiastic to acquire more knowledge of the historical and cultural background of the place to fulfill their need for authentic experience. The tourist who has a positive cognition tends to perceive existential authenticity more profoundly. As such, like the earlier consumer-based authenticity models (e.g. Zhou et al., 2013), guests’ attitude is considered in the mutual authentication model.

Guests’ motivation: Motivation is an important psychological factor that influences tourist perceptions of the objective and existential authenticity of ICH, which, in turn, affects tourists’ expectations (Gnoth, 1997). Tourist motivation is the primary driver to interpret tourist behavior in participating e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

in ICH activities. The motivation to visit ICH locations has been grouped into several aspects, of which some are quite similar to each other: mental relaxation, engagement with a calm atmosphere, discovering new places and things, gaining knowledge, having a good time with friends, having a religious motivation, visiting cultural and historical attractions and having an interest in history (Lee, 2009). Tourists perceive high objective and existential authenticity when they undertake ICH experiences which have a long history and many historical attractions including a deep cultural connotation. This is because tourists’ historical and cultural motives are usually linked to perceptions of highly authentic value. The perception of the authenticity of ICH influences tourist loyalty to revisit the location or event. In the previous consumer-based authenticity models (e.g. Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013), motivation was considered a major factor influencing the objective and existential authenticity of tourist attractions. Likewise, we view guests’ motivation to be a significant factor in the mutual authentication model.

Finding authentic objects: While guests’ attitude and motivation are important to making themselves participate in ICH tourism, guests’ http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

perceptions about the objects they see and the cultural events they enjoy during the visit are important as well. The objects associated with the cultural events (e.g. special design of the statues used for worship in religious festivals, the taste and quality of local foods, the design and making of local crafts) represent the identity of the particular ICH (UNESCO, 2011). Tourists, being outsiders, can perceive the uniqueness of the objects based on their knowledge of objects and products from other areas and information from other sources (Oh, 2005). When visiting ICH sites, they want to experience the local food and purchase locally made craft. This is particularly evident in a traditional festival when they get closer to the host, for instance, when the guests eat local food together with the community. Tourists also want to buy the local costumes which can simulate an authentic experience of this object by wearing them. If the tourists find any unique object during their ICH experience, this would influence their perception of its authenticity (Chhabra et al., 2003). Through finding authentic objects, guests can deeply connect to the hosts who are involved with making or providing these objects. This reinforces their belief in the objective authenticity of this ICH. Therefore, this guest factor is included in the mutual authentication model.

Finding authentic experiences or events: During ICH tourism, tourists find unique psychological and spiritual attachment and feeling when participating in cultural practices (Richards, 2018). At a destination which has both cultural and natural attributes (Esfehani and Albrecht, 2018), the experience of ICH can be presented in a special arrangement of events like cultural programs, celebrations, connections with the cultural history and natural features and unique religious and spiritual experiences in a calm and peaceful atmosphere. If the tourists find any unique cultural and natural experiences or events that satisfy them as authentic, then that experience would influence their perception of authenticity of its ICH. This guest factor is included in the mutual authentication model because it would help to determine tourists’ perception of the existential authenticity of ICH.

Mutual authentication of ICH and its relation to tourism development and community empowerment

In the mutual authentication process, the common perceptions of the hosts and guests about the authenticity of ICH would be determined through the influence of host and guest factors. While there might be some differences between http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

hosts’ and guests’ attitude and motivation concerning the community’s ICH, the close interaction of hosts and guests through tourism would fill the gaps. Host communities can showcase historical objects or sell unique traditional crafts to the tourists, labeling these as authentic. As well, a guest can identify some of those objects or products as authentic, based on their own knowledge and experience. Similarly, the cultural events practiced by the hosts or enjoyed by the guests can be distinguished as unique by both hosts and guests. The objects and cultural practices recognized by hosts and guest as unique and representative of the local community would be defined as authentic ICH.

Since hosts and guests participate in the mutual authentication process while interacting through ICH tourism, authentication of ICH by the hosts or the guests will influence their support for tourism or their satisfaction and loyalty to tourism, respectively. Hosts’ strong belief in their ICH’s authenticity would encourage them to provide support for tourism through personal or institutional involvement (Zhou et al., 2015). Likewise, the guests would have a high level of satisfaction when experiencing authentic ICH and loyalty to the ICH attractions, showing a willingness to revisit the destination and recommend it to others (Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013).

The mutual authentication of ICH will ultimately impact community empowerment through tourism. Economic benefit from ICH-based tourism (selling traditional crafts, food, and accommodation for tourists) will enhance the economic empowerment of the community. The guests also make a major economic contribution to valuing the traditional authentic objects and events, in compensation for satisfying their touristic consumption of the ICH. Similarly, the psychological empowerment of the community will be enhanced by owning the authentic ICH (objects and traditional practices) and positioning themselves as a unique community in the global society. Participating in the authentic traditional cultural practices individually or as a group can increase social cohesion and shared feelings, enhancing the social empowerment of the community. Everyone in the community can recognize their own identity with respect to their authentic ICH. Further, local institutions and leadership can be developed for managing ICH (e.g. organizing traditional cultural events, managing historical objects), which ensures the political empowerment of the community.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The authenticity of ICH has been a major concern in ICH-based tourism development to preserve and sustain it in the face of commodification due to the influence of modern socio-economic changes. In the search for an appropriate authentication approach, various models have been proposed in the recent literature for evaluating the authenticity of tourist attractions including ICH based on host and guest perspectives, for instance, the consumer-based authentication model (Cho, 2012; Kolar & Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013) and the host authentication model (Zhou et al., 2013). These models consider hosts’ and guests’ perspectives separately without showing the influence of their mutual perceptions on the authentication of ICH. Nor do these models take into account how the authenticity of ICH is linked to community empowerment.

This study proposes a conceptual model of mutual (host-guest)

authentication of ICH, which can integrate both hosts’ and guests’ perspectives in the authentication process and can be related to community empowerment. The model includes several factors: hosts’ attitude and motivation towards ICH, their psychological and economic benefit from 174 e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

ICH, and their participation or involvement in the ICH, which can influence its authentication by host communities. Also, the guests’ attitude and motivation concerning ICH as well as the hosts’ experience of the traditional objects, events and/or environment are considered as factors that influence the authentication of ICH by the guests.

The conceptual model emphasizes power relationships between host and guest and combines their perspectives in the authentication process. The model suggests that tourism based on authentic ICH influences community empowerment across the political, social, psychological and economic domains. This model may be useful for understanding power relations in the authentication of ICH and improving sustainable tourism through community empowerment. Further investigation is required to confirm the application of the conceptual model in various contexts of ICH-based tourism and other tourist attractions. The model can be further developed incorporating other stakeholders, including government and tour operators, to ensure the sustainable management of ICH, tourism development and community empowerment.

REFERENCE

Alexander, N. (2009) ‘Brand

authentication: Creating and

maintaining brand auras’, European Journal of Marketing, 43(3/4), 551562.

Asplet, M. and Cooper, M. (2000) ‘Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: The question of authenticity’, Tourism Management, 21(3), 307–312.

Besculides, A., Lee, M.E. and McCormick, P.J. (2002) ‘Residents' perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism’, Annals of tourism research, 29(2), pp.303-319.

Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R. and Long, P. (2014) ‘Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism:

Strengthening the theoretical

foundation through a Weberian lens’ Annals of Tourism

Research, 49, 33-50.

Casey, E. S. (1993) Getting back into place: Toward a renewed

understanding of the place-world. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Chhabra, D. (2010) ‘How they see us: Perceived effects of tourist gaze on the Old Order Amish’, Journal of Travel Research, 49(1), pp.93-105.

Chhabra, D., Healy, R. and Sills, E. (2003) ‘Staged authenticity and heritage tourism’, Annals of tourism

research, 30(3), pp.702-719.

Cho, M.H. (2012) ‘A study of authenticity in traditional Korean folk villages’, International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism

Administration, 13(2), pp.145-171.

Cohen, E. (1988) ‘Authenticity and commoditization in tourism’, Annals of tourism research, 15(3), 371-386.

Cohen, E. (2007) ‘Authenticity’ in tourism studies: Aprés la lutte’, Tourism

Recreation Research, 32(2), 75-82.

Cohen, E. and Cohen, S. A. (2012) ‘Authentication: Hot and

cool’, Annals of Tourism

Research, 39(3), 1295-1314.

Cole, S. (2007) ‘Beyond authenticity and commodification’, Annals of

Tourism Research, 34(4), 943-960.

del Barrio, M.J., Devesa, M. and Herrero, L.C. (2012) ‘Evaluating intangible cultural heritage: The case of cultural festivals’, City, Culture and Society, 3(4), pp.235-244.

Di Castri, F. (2004) ‘Sustainable tourism in small islands: Local

empowerment as the key factor’, Insula-Paris, 13(1/2), 49.

Esfehani, M.H. and Albrecht, J.N. (2018) ‘Roles of intangible cultural heritage in tourism in natural protected areas’, Journal of Heritage

Tourism, 13(1), pp.15-29.

Fiorello, A. and Bo, D. (2012), ‘Community-based ecotourism to meet the new tourist's expectations: An exploratory study’, Journal of Hospitality Marketing &

Management, 21(7), 758-778.

Giudici, E., Melis, C., Dessì, S. and Francine Pollnow Galvao Ramos, B. (2013) Is intangible cultural heritage able to promote sustainability in tourism?’, International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 5(1), 101-114.

Gnoth, J. (1997) ‘Tourism motivation and expectation formation’, Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), pp.283– 304.

Gnotha, J. and Wang, N. (2015) ‘Authentic knowledge and empathy in tourism’, Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 170-172.

Greene, T. (1996) Cognition and the management of place. In B. L. L. Driver, G. Peterson, G. Elsner, d. Dustin and T. Baltic (Eds.), Nature and the human spirit: Toward an expanded land management ethic. State College, PA: Venture

Publishing.

Greenwood, D.J. (1977) ‘Culture by the Pound: An Anthropological

Perspective on Tourism as Cultural Commoditization’, In Smith, V.L. (Ed), Hosts and Guests (pp.129139). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Islam, M. M., Sunny, A. R., Hossain, M. M. and Friess, D. A. (2018) ‘Drivers of mangrove ecosystem service change in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh’, Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 39(2), 244

265.

Kolar, T. and Zabkar, V. (2010) ‘A consumer-based model of

authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing?’, Tourism Management, 31(5), pp.652-664.

Lee TH. (2009) ‘A structural model to examine how destination image, attitude, and motivation affect the future behavior of tourists’, Leisure Sciences, 31(3), pp.215–236.

Loulanski, T., & Loulanski, V. (2011) ‘The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: a meta-study’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(7), 837-862.

McIntosh, A.J. and Prentice, R.C. (1999) ‘Affirming authenticity: Consuming cultural heritage’, Annals of tourism research, 26(3), pp.589-612.

Mkono, M. (2013) ‘Hot and cool authentication: a netnographic

illustration’, Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 215-218.

Moswete, N., & Thapa, B. (2015) ‘Factors that influence support for community-based ecotourism in the rural communities adjacent to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana’, Journal of

Ecotourism, 14(2-3), 243-263.

Moyle, B., Glen Croy, W., & Weiler, B. (2010) ‘Community perceptions of tourism: Bruny and Magnetic

islands, Australia’, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 15(3), 353-366.

Oh, S. H. (2005) Understanding of tourism and culture. Seoul: Hyungseul.

Richards, G., 2018. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, pp.12-21.

Scheyvens, R. (1999) ‘Ecotourism and the empowerment of local

communities’, Tourism Management, 20(2), 245-249.

Subramaniam, P.R. and Silverman, S. (2007) ‘Middle school students’ attitudes toward physical

education’, Teaching and teacher education, 23(5), pp.602-611.

Theodori, G. and Luloff, A. (1998) ‘Land use and community attachment’, 7th International Symposium on Society and Resource Management,

University of Missouri.

Trilling, L. (1972) Sincerity and Authenticity. Oxford University

Press: London.

Tuan, Y. (1974) Topophilia: A study of environmental perceptions, attitudes and values. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

UNESCO. (2011) What is intangible cultural heritage? UNESCO. Retrieved 2 November from https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01851-EN.pdf

Wang, N. (1999), ‘Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience’, Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349-370.

Wheatley, M. J. and Kellner-Rogers, M. (1998) The paradox and promise of community. In F. Hesselbein, M. Goldsmith, R. Beckhard and R. F. Schubert (Eds.), The community of the future (pp. 9–18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Yang, J., Ryan, C. and Zhang, L. (2013) ‘Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism’, Tourism Management, 35, pp.82-93.

Yoon, Y. and Uysal, M. (2005) ‘An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model’, Tourism

Management, 26(1), pp.45-56.

Zanna, M.P. and Rempel, J.K. (2008) ‘Attitudes: a new look at an old concept’, in Fazio, R.H. and Petty, R.E. (Eds), Attitudes: Their

structure, function, and

consequences, Psychology Press, New York, pp. 7-17.

Zhou, Q.B., Zhang, J. and Edelheim, J.R. (2013) ‘Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumer-based model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic

landscape’, Tourism

Management, 36, pp.99-112.

Zhou, Q.B., Zhang, J., Zhang, H. and Ma, J. (2015) ‘A structural model of host authenticity’, Annals of Tourism Research, 55, pp.28-45.

Zhu, Y. (2012) ‘Performing heritage: Rethinking authenticity in

tourism’, Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1495-1513.

http://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eot

177

e-ISSN: 2407-392X. p-ISSN: 2541-0857

Discussion and feedback