THE VALENCY CHANGE STRATEGY OF ADJECTIVES IN INDONESIAN

on

e-journal of linguistics

THE VALENCY CHANGE STRATEGY OF ADJECTIVES IN INDONESIAN

Mirsa Umiyati

Magister Program of Linguistic Warmadewa University

Prof. Dr. Ketut Artawa, M.A., Ph.D.

Study Program of Linguistics, School of Postgraduate Studies, Udayana University

Prof. Dr. Ida Bagus Putra Yadnya, M.A

Study Program of Linguistics, School of Postgraduate Studies, Udayana University

Prof. Dr. I Nyoman Suparwa, M.Hum.

Study Program of Linguistics, School of Postgraduate Studies, Udayana University

Abstract

Makalah ini menerangkan tentang variasi kategori kelas kata yang bisa mengikat satu argument. Kemampuan mengikat satu argument yang sangat identik dengan verba intransitive menyebabkan kategori lain yang mempunyai kemampuan sama dikatakan berfungsi sebagai predikat intransitif (intransitive predicate) dalam konteks pembahasan transitivitas. Kategori lain yang bisa mengisi lot tersebut adalah adjektiva, nomina dan preposisi. Analisis LFG mampu menerangkan perbedaan dan cara menentukan suatu kata sebagai predikat dalam suatu konstruksi kalimat atau tidak sebagai predikat. Bagaimana variasi dari masing-masing kategori tersebut dalam kalimat?. Paper ini akan mengulas dengan detail perihal tersebut.

Keywords: Argumen, klausa simple, predikatif Intransitive

The discussion of valence in relation to verbs is not a new topic for linguists all over the world. When valence is discussed, it also includes the discussion of verbs which occur as predicates. Verbs can bind a number of arguments to be placed in certain position within clauses. In fact, predicates in the Indonesian language are not only filled by verbs but also by other word categories. This means that adjectives in the Indonesian language can also become the predicates. Then the question that may emerge is whether or not the adjectives can bind a number of arguments. If it is possible for adjectives to bind a number of arguments, how many arguments can be bound by adjectives? What strategies are adopted by adjectives to bind arguments? These questions are the focus of this paper.

The concept of valance refers to the number of nominal arguments needed in a clause. The number of arguments needed in a clause depends on the semantic features of the verbs as the main constituent in the clauses. If the predicate of the clause needs two core arguments, these arguments need to occur explicitly. Conversely, if the predicates only need one core argument, then the clause will not be grammatically correct. If the predicate only takes one core argument, then two arguments occur in the similar clause, this clause is considered non grammatical.

The concept of valance is twofold: syntactical valency and semantic valency. Syntactically, grammatical valency is the number of argumentwhich is needed by verbal predicate in a clause morpho syntactically. Semantic valency is the number of argument which is semantically needed by verb.(Payne, 1997:169-170; Van Valin Jr. dan LaPolla, 2002:147-150; Haspelmath, 2002:210-211).

This demonstrates that the concept of valence is understood as an element that is strongly related to the verb as the main part of a clause. In this paper, the concept of valance is related to the category of adjective. The present research is being undertaken because the adjective class can also become the predicate of a clause. If adjectives can function as predicates, they are also able to bind a number of arguments. How many arguments can possibly be bound by an adjective depends on the semantic features of the adjectives that functions as predicates. Basic adjectives can only bind a core argument. There are also a number of adjectives that can bind two core arguments. Further discussion concerning the ability of adjectives to bind a number of arguments can be seen below.

Singled-valance adjectives are adjectives that can only bind one core argument. The adjective class that can be classified as singled-valance adjective is basic adjectives which do not undergo morphological process including affixation, reduplication, and composition. The following examples (1-10) represent singled-valance adjectives used in sentences/clauses:

-

(1) Monika begitu Bahagia ketika akhirnya dia dapat membawa laki-laki itu kehadapan orang tuanya (JRM, 2002: 1)

-

(2) Jono heran ketika melihat mendungnya wajah isterinya (DTW, 2007)

-

(3) Ia kagum atas kemajuan karir yang diperoleh Janus (MT, 2001: 49).

-

(4) Sebenarnya aku malu kalau ayah kawin lagi (DTW, 2007).

-

(5) Isterinya pelit, suaminya royal (JRM, 2002: 24)

-

(6) Badannya lemah karena baru sembuh dari sakit (DTW, 2007: 645).

-

(7) Sorot matanya tajam bagai silet memandangku dengan tatapan mencemooh (JK)

-

(8) Bu Azwar orangnya rapi (MDAP 2003)

-

(9) Rumah ayah sepi ketika aku tiba di sama (MBA)

-

(10) Pita kuningnya serasi dengan gaunnya (BIS, 2003)

The clauses (1 – 10) above are adjectival predicates which involve the use of singled-valence adjectives. The adjective bahagia in (1); heranin (2); kagum in (3); malu in(4); pelit in royal in (5); lemah in (6); tajam in (7); rapi in (8); sepi in (9), and serasi in (10), are classified into singled-valency adjective because they can only bind one core argument.The only argument bound by these adjectives are Monika in (1); Jono in (2); iain (3); aku in (4); isterinya and suaminya in (5); badannya in (6); sorotmatanya in (7); Bu Azwarorangnya in (8); rumah ayah in (9); and pita kuningnya in (10). In addition to basic adjectives, derived adjectives in Indonesian also belong to the category of singled-valence adjective through affixation, reduplication, and composition. The single valence derived adjectives are represented in the following data (11 – 25):

-

(11) Dia perempuan baik-baik (JK)

-

(12) Anak itu ayu-ayu semua (PB, 2010).

-

(13) Cewek-cewek di kelasku bening-bening (SLDK, 2009).

-

(14) Cowok-cowok kedokteran terkenal gagah-gagah (SNI, 2007)

-

(15) Bidan di sini galak-galak (SBM).

-

(16) Oderan semakin melimpah (BHT, 2010).

-

(17) Dadanya hangat bergelora (PK).

-

(18) Harman benar-benar terkejut (CMDB, 2010).

-

(19) Memerah paras Adel karena keterusterangan dokter itu (DUJS, 1999).

-

(20) Kemarahanku sangat mengagetkan (JMH, 2005).

-

(21) Wajahnya tampan, orangnya pintar, baik budi pula (DTKJ, 1986)

-

(22) Sekujur tubuhnya basah kuyub (CSA, 2010).

-

(23) Dia ramping dan lemah gemulai seperti penari (DSCB, 2005).

-

(24) Perusahaannya pasti akan hancur lebur (DBAD, 2010).

-

(25) Gadis itu memang cantik jelita (DBAD, 2010).

The adjective baik-baik in (11); ayu-ayu in (12); bening-bening in (13); gagah-gagah in (14); galak-galak in (15) and benar-benar terkejut in (18) are derived adjectives through reduplication. The adjectives melimpah in (16); hangat bergelora in (17); memerah in (19); and sangat mengagetkan in (20) are derived adjectives through affixation. The adjectives baikbudi in (21); basah kuyub in (22); lemah gemulai in (23); hancur lebur in (24); and cantik jelita in (25) are derived adjectives that have undergone composition morphological process. All adjectives in (11 – 25) are classified as singled-valence adjectives which can only bind one core argument namely dia in (11); anak itu in (12); cewek-cewek di kelasku in (13); cowok-cowok kedokteran in (14); bidan di sini in (15); oderan in (16); dadanya in (17); Harman in (18); paras Adel in (19); kemarahanku in (20); orangnya in (21); sekujur tubuh in (22); dia in (23); perusahaannya in (24); and gadis itu in (25). There is a high quantity of sentences in the evidence presented above which demonstrate adjectives functioning as subjects. This demonstrates that in Indonesian adjectives are more frequently used as subjects than as objects or compliments. The constituent structure of single adjectival clauses can be demonstrated in the tree diagram as in (26) and (27) based on the single-valence adjective in (10) and derived adjective in (12).

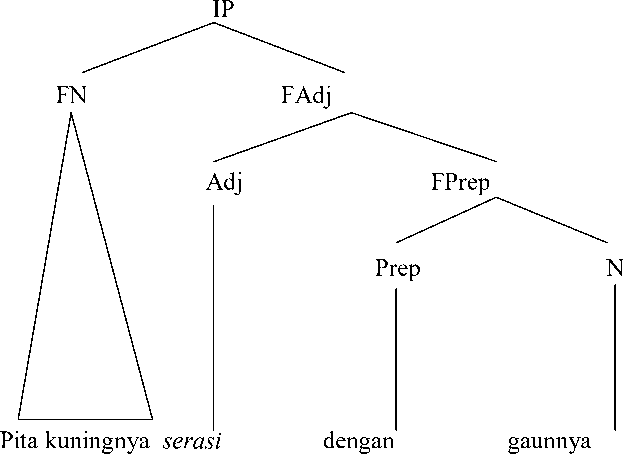

(26)

(27)

N Det Adj

QF

Anak itu ayu-ayu semua

In constituent structural diagram (26), it is obvious that the adjectival predicates serasionly binds a core argument which takes its subject position, pita kuningnya, and one prepositional phrase that functions as adjunct, that is dengangaunnya. This also occurs in the derived adjective ayu-ayu in (27) which it is categorized as a single-valence adjective because it can only bind a core argument anakitu, which functions as subject in the clause.

Doubled-valence adjectives are the adjectives that are able to bind two core arguments. These adjectives function as clausal predicates. Double-valence adjectives which are basic adjectives can be found in the following sentences (28 – 43):

-

(28) Saya benci orang itu (ELI)

-

(29) Ardila suka gaun berwarna orange (ELI)

-

(30) Aku takut dia akan jenuh mendengarnya (JB, 2002)

-

(31) Aku malu ayah kawin lagi (DTW, 2010).

-

(32) Dia yakin orangtuanya pastiakanmenerimanya (SKS, 2007)

-

(33) Saya yakin dialahpelakunya (ELI).

-

(34) Aku lebih bangga anakku babak belur karena berkelahi dari pada ngumpet kayak tikus! (SMJ, 2007: 90: 8 – 10).

-

(35) Aku segan kuliah (DSC, 1980: 126).

-

(36) Dia takut mimpinya kembali lagi (BIP, 2003: 16: 12 – 13).

-

(37) Jangankatakan kamu takut gelap (BIP, 2003: 97: 21 – 24).

-

(38) Alfian begitu takut kehilangan isterinya (BIP, 2003: 171, 20)

-

(39) Wanita tua itu takut Alfian akan mengusirnya lagi (BIP, 2003: 281: 20 – 22).

-

(40) Kami khawatir jumlah korban tewas bertambah (JP, 9 Maret 2004).

-

(41) Saya yakin orang asing lebih menghargai kita (KMI, 2009: 107, 19)

-

(42) Aku muak hidup bersamanya (JRM 2002: 148, 24)

-

(43) Dia rindu kamarnya yang besar, kamarnya sendiri, bukan kamar sempit yang harus dibaginya berdua denganTika (MDAP, 2001: 173, 17 – 19).

All predicative adjectives in clauses are classified as doubled-valence adjectives. These two adjectives can bind two core arguments. The adjective benci in (28) can bind two core arguments saya and orang itu. The adjective suka in (29) can also bind two core arguments, Ardila and gaun berwarna orange. Similarly, the adjectives takut in (30), (36 – 39) can bind two core arguments, aku and dia in (30), dia and mimpinya in (36), kamu and Gelap in (37), Alfian and kehilangan isterinya in (38), and wanita tua itu and Alfian in (39). The adjective in (31) is also a double-valence adjective because it can take two core arguments aku and ayah. This also occurs in the adjective yakin in (32), (33) and (41) are classified as double-valence adjectives since they involve two core arguments namely dia and orang tuanya in (32), saya and dia(lah) in (33), and saya and orang asing in (41). Other adjectives (lebih) bangga in (34), muakin (42), and rindu in (43), can also take two core arguments that is aku and anakku in (34), aku and hidup bersamanya in (42), dia and kamarnya yang besar in (43). These three last adjectives are categorized as double-valence adjectives.

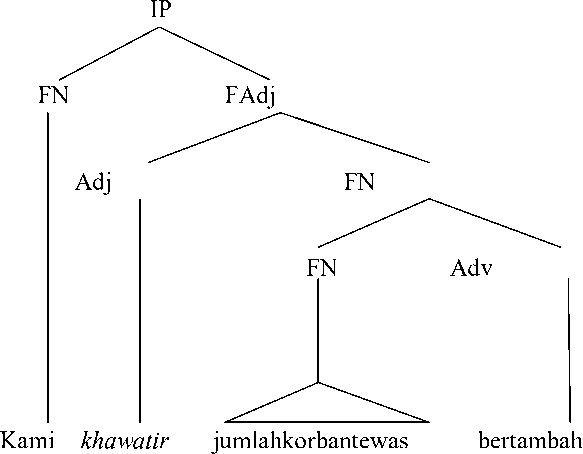

The representation of constituent structure of double valence adjectival clauses can be shown in the tree diagram as in (44) based on data (40) above:

In the tree diagram (44), it can be seen that adjective khawatir binds two arguments, kami which syntactically occurs in the subject position, and jumlah korban tewas which syntactically occurs in the object position of that clause.

As has been discussed in (2), the investigation of valence changes is actually a discussion on types of verb constructions used as main clause constituents.These constructions determine the number of arguments that a verb should take. In relation to the change of verb valence, there are three types of construction that are used as the bases of discussion namely causative, applicative, and resultative. Discussion of adjectival valence is rare. Although it is not common, I will present and show the strategy of valence changes of adjectives in the Indonesian language. Thiscommences from the discussion on causative and applicative constructions. These two constructions are closely related to the valence changes of adjectives.

Causative is an event that possibly occurs because one has done something or because something has happened. (Goddard, 1998:260). Any causative construction involves two components that are always interrelated i.e. the cause and effect. The cause and the effect are called a micro situation (micro-situation). Both of these micro situation form a macro situation (macro-situation) called as the causative situation (Comrie, 1989: 165). In linewith Comrie(1989)andGoddard(1998)above, Shibatani(1976)statedthat the easiest waytodefine thecausativeconstructionis todescribe thecausativesituation. A causativesituationis a situation thatconsists oftwoevents thatare relatedto each other, whichshowcause andeffect. An effect (t2) always occurs after and as a result of the cause (t1). The reciprocal relationshipbetween causeand effectalwaysdependsentirely on thecause. That is, theeffect will not occur ifthere is no event that can be considered as ‘the cause’.

In the classification of causative constructions, Comrie (1989: 165-174) used two parameters, namely the formal parameter and semantic parameter. Based on the formal parameter, which is also called a parameter morphosyntax, causative construction is divided into three types, namelyanalytic causative, the morphological causative, and the lexical causative. The analytic causative is a causative that is formed by means of causative verbs; the morphological causative is formed through affixation causative, and lexical causative is expressed by means of lexiconswithout any morphological process. Based on the semantic parameter, Comrie (1989) classified causative construction by utilizing two subordinate parameters that are based on the level of control accepted by thecauseeand based on the adjacency of the cause and effect in macro-situation (causative). Based ontheacceptablelevelof control, Comrie, (1989: 171)distinguished two kind of causatives namelytruecausativeand permissive causative. In truecausative, the componentshave theabilitytocauseand effect,while permissivecausativeshave the abilitytopreventthe occurrenceand effect.Agent, as the causer inthecausativeconstructionhas the potentialto control ‘the causee’.

Furthermore, in terms of a relation between causer and cause Comrie (1989: 171) classified causative instruction into; direct causative and indirect causative. Direct causative is the causative in which causer and causee have a very close relationship. The indirect causative is the causative in which causer and causee have a distant relationship. In indirect causative the causee always occurs long after the causer.

Unlike Comrie (1989),Kozinsky and Polinsky(1993: 178), classifiedcausative in terms of verb coding.Coding classifies causative constructions into two groups.The first group is morphological causative (sometimes referred to as synthetic causative) and the second group is syntactic causative (also known as causative analytic). Morphological causative is a construction that is syntactically monoclausal. This construction uses a causative verb whose functions are embedded as a single syntactic unit. Conversely, periphrastic causative or syntactic causative is a construction that is syntactically monoclausalbut has two separated syntactic units.

Causative adjective constructions in Indonesian are usually signaled by the verb merasa and the specifierssangat, lebihand agak. With the presence of such words, it is clearly seen that there is a relation between the causer and causee. Data for adjectival analytic causative in Indonesia are as follows.

-

(45) Aku merasa ngeri hanya karena mendengar ceritanya. (SKY : 2003)

(46)Makeda atau Krisanti memang merasa panik ketika mendengar dirinya akan dipulangkan ke Afri. (SN4 : 2006)

-

(47) Mata yang hitam itu mengikuti setiap gerak-geriknya sehingga dia merasa gerah. (BAM : 2003)

-

(48) Begitu nyerinya tatapan itu sampai Vania ikut merasa perih. (CSA : 2010)

-

(49) Sebelum menemukan Nita, aku tidak dapat merasa tenang. (DBKD : 1996)

-

(50) Saya tidak merasa nyaman dengan ulah orang itu (ELIS).

Adjectival phrases on data (45-50) are merasangeri (45), merasapanik (46), merasagerah (47), merasaperih (48), merasatenang (49) danmerasanyaman (50), all of them have causative meaning. Causative type that forms adjectival phrase constructions on these five data is analytic causative marked by the word merasa. As a causative construction adjectival clause (45-50) each has two components, which are causer and causee. The causers of the five clauses are mendengarceritanya (45), mendengardirinyadipulangkankeAfri (46), mata yang hitamitumengikutisetaiapgerak-geriknya (47), begitunyerinyatatapanitu (48), belummenemukan Nita (49), danulah orang itu (50). The causee of the five clauses arengeri(45), panik (46), gerah (47), perih (48), tenang (49), dannyaman (50). The fact found on the data (45-50) above is that the presence of merasa makes adjectives appear as causers so that causative construction on each of the five clauses is formed. Based on control level received by the causee, as part of a semantic parameter, adjectives in Indonesian contain true causative. It is said so because the causee in adjective constructions of Indonesian always appears from the causer. Thus the causer has ability to create effects. Actor argument, as the causer in this true causative construction, is potential to

control whether or not the causee can occur. Furthermore, based on the close relationship between the causer and the causee, adjective causatives in Indonesian belong to direct causative, the causative in which the causer and the causee have a very close relationship. The effects the causee experiences, in this case, are very close to the causer. (check again the data 45-50 above).

If the causative construction focuses more on mutual relationship between two micro components, the causer and the causee, then the applicative construction focuses more on aspect of the increase of argument number (Shibatani, 1996: 156). Therefore, discussions about applicative is very closely related to verb transitivity. Verbs as clause headappear naturally at the same time with a number of arguments as head clause constituents as the semantic requirement of the verbs themselves. If verbs as the clause head change morphologically the number of argument also changes. Change of argument number or change of valensy following the verbs is mainly caused by affixation processes of the verbs (mainly takes place in agglutination type of languages). This can be proven with examples adopted from Shibatani (1996: 159), (i) Sayamenduduk-ikursi and (ii) Sayaduduk di kursi. The verb duduk is a singled-valensy verb. It means that the verb dudukneeds only one head argument with a semantic role Ag. In clause (ii), saya is the only head argument functioning as a subject, while kursi is not a head argument functioning as an adjunct or oblique. If the verb duduk is added with an applicative affix –i so it becomes duduki, then a change of valensy occurs here, from singled valensy to doubledvalensy because the verb duduki semantically needs two arguments, which are Ag and Ps, as in the clause (i) above. Thus, saya and kursi in (i) are head arguments, which semantically acts as Ag and Ps respectively. The transitive verb beli also needs two arguments, which are Ag (the one who buys) and Ps (something that is bought). If the verb beli is added with benefactive affixes me-kan so it becomes membelikan, then a valensy change occurs from doubled-valensy verb to triple-valensy verb because the verb memberikansemantically needs three head arguments, which are Ag, Ben and Tm, as in Ibumembelikanronalbukugambar.

The increase of number of arguments as the effect of applicative proposed by Shibatani above is something that cannot be denied because lingual fact has proven its trueness. Applicative, however, is not oriented merely to the increase of argument number. In the applicative there is also an act transfer mechanism from Ag to Ps. Patient, in this case, becomes a

target of locus from the act done by Ag. Since the target is Ps, the increase of argument number occurs. The followings are adjective applicative construction types in Indonesian:

-

(51) Suaranya sedater air mukanya (DBKD, 1996)

-

(52) Wajahnya tidak setampan Soni (MDAP, 2001: 261, 1-6).

-

(53) Mas Herman terlalu memanjakan gadis itu (BIS 2003)

-

(54) Majikannya tidak serajin dia mencari uang (OTB, 2004)

-

(55) Saya tidak punya baju sebagus itu (JRM, 2002).

Adjectives in the clause (51-55) above are; sedatar (51), setampan (52), memanjakan (53), serajin (54), sebagus (55). These adjectives are modified ones from the original adjectives datar, tampan, manja, rajin and bagus. These basic adjectives are singled-valensy adjectives because they can only attain one head argument. They, therefore, act like intransitive verbs in terms of their ability to attain head arguments. After they are added with prefiksse- (data 51, 52, 54 and 55) and with affix me-kan (data 53), a valensy change occurs from singled-valensy adjectives to doubled-valensyadjentives. Adjective sedatar (51) attains two head arguments suaranya and air mukanya. Adjectivasetampanwith negation tidak (52) also attains two head arguments wajahnya and Soni. Adjective memanjakanwith adverb terlalu (53) attains two head arguments Mas Herman and gadis itu. Adjective serajin with negation tidak (54) attains two head arguments majikannya and dia. Finally adjective sebagus (55) also attains two head arguments baju and itu. In this context ituis considered an argument because it refers to a noun baju, which ismentioned clause-initially. Based on the data proposed above, we can see that adjectives in Indonesian can attain a number of arguments. From the number of arguments they can attain, adjectives in Indonesian can be classified as singled-valensy adjectives because they can attain one argument and doubled-valensyadjectives because they can attain two head arguments. The valensy change mechanism of adjectives in Indonesian occurs through two constructions, i.e. analytic causative and applicative causative.

The Indonesian language is one of the languages faced the overlapping problems in the word classes. Similar with any other languages that also experiencing the same phenomenon in the overlap‘s words classes, Indonesian adjective is the most ambiguous in word classes’ overlaps. Syntactically, the thoroughness in the discussion of the complement clause could be the important key for making correction in reformulating the types of Indonesian typology. The

second reason, the morphological analysis, the findings in regarding the specific affixes that claimed to be very productive in shaping a particular the word class is also a potential suspect in the other word classes’ form especially in a particular clauses.

Aissen, Judith. 1982. Valence and Coreferennce. in Paul J. Hopper and Sandra A Thompson Artawa, Ketut 1998. ‘Ergativity and Balinese Syntax’. In NUSA Vol. 42--44. Jakarta : Center of

Langauge and Culture Studies.

Comrie, B. 1983, 1989. ‘Linguistic Typology’ in Newmeyer, F. J. (Ed.) Linguistics : The

Cambridge Survey. Vol I. Hal : 447--467. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R.M.W. 1994. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R.M.W. 2010. Basic Linguistic Theory, Grammatical Topics, Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Discussion and feedback