English Second Language Strategies For Teaching Irregular Plural Noun Morphological Inflection

on

e-Journal of Linguistics

Available online at https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eol/index

Vol. 16, No. 2, July 2022, pages: 156—169

Print ISSN: 2541-5514 Online ISSN: 2442-7586

https://doi.org/10.24843/e-jl.2022.v16.i02.p01

English Second Language Strategies For Teaching Irregular Plural Noun Morphological Inflection

Farisani Thomas Nephawe University of Venda, South Africa Farisani.nephawe @univen.ac.za ftnephawe@gmail.com

Article info

Received Date: 26 January

2022

Accepted Date: 31 January 2022

Published Date: 31 July 2022

Keywords:*

irregular nouns, morphemes, morphological inflection, word classes, zero-inflection

Abstract*

Nouns are one basic component of the syntactic category of the English language because they can be used as subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, subject complements, object complements, appositives, or adjectives of sentences. Transforming regular nouns from singular to plural forms is comprehensible since the usual patterning is used. Converting irregular nouns from singular to plural forms causes difficulties to non-native learners of English since conversion does not follow the usual patterning. The study examined English second language strategies for teaching irregular plural noun morphological inflection to Grade 8 learners. The researcher used a quantitative research design because the results could be analysed mathematically and statistically. A probability technique was used to randomly sample 25 participants whose ages ranged from 14 to 16 at Ndaedzo Secondary School in Limpopo Province, South Africa. A statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22 was utilised to interpret the findings. Initially, the participants were incompetent in this regard but after utilising the ‘irregular plurals reversi memory game’, and ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ strategies, learners’ performance improved remarkably. The research recommends teaching irregular plural noun morphological inflection using the games.

Parts of speech are a major building block the English language grammar because they are found elsewhere in communication. However, they pose numerous challenges to the second language learners (L2) since their home languages do not have similar syntactic categories. Parts of speech comprise verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners, and interjections (Khan, 2020). The grouping of these word classes, namely: open (lexical) and closed word (function) classes requires learners’ competency in the use of the English language. According to Nordquist (2020), word classes are grouped according to their functions in sentences. Nouns, verbs, adjectives are grouped into ‘open word’ classes because

they can be transformed from one class to another. For example, noun to verbs in ‘song /sing’, noun to nouns, for example, ‘song/songster’, nouns to adjectives in: ‘adjustment/adjustable’, adjective to adjective in ‘black/blackened’, and vice versa. In contrast, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles or determiners, and interjections. cannot be transformed from one class to another. Hence, it is difficult for the L2 learners to be competent in the morphological inflection of the irregular plural nouns without basic understanding of nouns.

Nouns are words or phrases referring to a person such as ‘Godfrey Chaucer’, an animal like ‘pig’, a place ‘Ottawa’, a quality as in ‘kindness’, an idea like ‘injustice’, action such as ‘modeling, or a thing like ‘computer’. They can be used as a subject or object of a sentence or as the object of a preposition than any part of the word classes. Even though the non-native languages have their respective nouns, transforming them from singular to plural forms in English causes tremendous difficulties because their morphological inflection is quite different. Nouns can be combined with determiners to serve as the subject of noun phrase or sentence, interpreted as singular or plural, and replaced with a pronoun to refer to an entity, quality, state, action, or concept (Merriam-Webster, 2021). The countable nouns are used after the articles ‘a’ or ‘an’, or after a number or any word referring to something greater than one, for example, ‘a stone’, ‘an apple’ or ‘trucks’. Non-countable/mass such as ‘sugar’ and ‘spices’ are not fronted with these articles. Nominal suffixes indicate plurality as in the noun colleges, genitive case in college’s or “plurality and genitive case in cumulation” (Schlechtweg & Corbett, 2021:384), for example, ‘colleges’.

Nouns, like verbs, have stems consisting of singular and plural regular and irregular stems. The number of a noun concerns inflectional morphology while morphemes incorporate meanings of words and how they are conjugated from singular to plural forms, for example, ‘dog/dogs’. Geiser (202:14) asserts that they are the “smallest meaningful element” in languages while morphology concerns words formation using affixes including prefixes, suffixes, and roots. As regards inflectional morphology, variation phenomena involve different parts of speech and different characteristics, namely: nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adverbs and quantifiers (Mendívil-Giró, 2021). English words are transformed from singular to plural forms using the inflectional morphemes and the derivational morphemes. The inflection adds a grammatical affix (Jurafksy & Martin, 2017) to the base forms or stem of words to modify their meanings or create new words of similar classes. Nonetheless, the derivation process involves word stem affixation resulting in words that are different from their classes. Irregular plural noun morphological inflectional comprises number, tense, agreement, or case to grammaticalise words and their meanings. Contrarily, morphology concerns the inner structure of words while morpheme entails the smallest unit of grammar. The grammar of words incorporates form, structure, meaning, relations between words, and the ways new words are formed (Audring & Masini, 2022). This becomes a difficult exercise as most L2 learners has little or no contact at all with the English language outside the classroom environment although having a good proficiency in it has become one most essential requirement and qualification (Naser, 2017). English grammar exerts numerous problems among learners as they cannot comprehend different mechanisms of inflection (Silver & Martins, 2012). Conway (1998) claims that:

The English language is overburdened with idiosyncratic grammatical features, a legacy of its eclectic accretion over 1500 years. One unfortunate consequence of this otherwise admirable richness is that automatically generating correct English is fraught with difficulty. Composing the simplest of sentences may require quite sophisticated semantic understanding to enable the correct syntax to be chosen. Even at the lexical level, it can be a complex matter to correctly inflect the individual words of a sentence to reflect their number, person, mood, case, etc.

Based on the preceding quotation, Conway postulates that English grammar competence calls for strategies for mastering the language as difficulties in the irregular plural noun morphological inflection know no border. Nordquist (2019:1) argues that since “there are no easy rules, unfortunately, for irregular plurals in English, they simply have to be learnt and remembered’. Not all nouns conform to the standard pattern. In fact, some of the most common English nouns have irregular plural forms, such as woman/women.

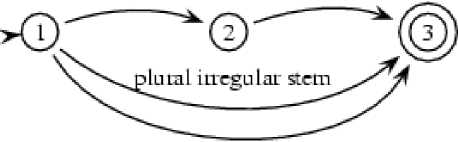

Nonetheless, difficulties in the inflection of irregular plural nouns can be minimised if comprehensive mastery is done. For example, in Monash University, Australia, a computational analysis of the morphological rules in the School of Computer Science and Software Engineering was captured to boost the irregular plural noun morphological inflection competence. In the process, the following ‘finite-state automaton’ was utilised to describe the inflectional morphology (Jurafksy & Martin, 2017) of nouns:

IiegLiIiirstcin ’s’

si IigLi Iai LLncgLi Iau stem

Adapted from Morphology: Word Formation, FSAs, and FSTs COMP-550

So far it is evident that sometimes, when two morphemes are combined, additional changes happen at the boundary. When combining the noun stem ‘box’, for example, with the plural morpheme ‘-s’ the noun ‘boxes’ is formed than ‘*boxs’. The ‘-e’ slips in between the stem and the suffix although the insertion of the suffix ‘-es’ at the morpheme boundary is not arbitrary. It is in line with a rule stating that an ‘-e’ is inserted when a morpheme ends in ‘-s’, ‘-x’ or ‘-z’ (Wall Street English, 2022) and is conjugated with the ‘-s’ suffix. As regards bound morphemes, inflectional morphology condenses linguistic information including case, gender, number, tenses, and agreement to a word, but a word retains its basic meaning rendering it a similar category.

Singular regular nouns can be changed into regular plurals using the suffix ‘-s’ or ‘-es’ (Wall Street English, 2022) to nouns ending in consonants including ‘s’, ‘x’, ‘ch’, ‘sh’, ‘o’, ‘y’, and ‘f’ (Tree Valley Academy, 2021). They follow a usual pattern of inflection from singular to plural nouns, for example, ‘cliff/cliffs’ and ‘bush/bushes’. The Albert Team (2021) postulates these suffixes make the inflection of regular plural nouns easier to learn, write or read. In contrast, the inflection of irregular plural nouns does not follow a usual pattern as there are various ways of inflection. For example, the vowels ‘-ou’ in ‘mouse’ and ‘louse’ can be replaced by ‘i’ and consonant ‘-s’ with ‘-c’ as in ‘mice’ and ‘lice’. The noun ending ‘-um’ becomes ‘-a’ as in ‘bacterium/bacteria’. Also, zero-inflection (Nordquist, 2020) can be used to form plural ‘spacecraft’ from the singular ‘spacecraft’. The irregular plurals nouns ending in ‘-f’ change the ‘f’ to a ‘-ves’ in ‘leaf/leaves’. However, some exceptions occur in the inflection of irregular nouns as in ‘proof/proofs’. The irregular nouns ending in -o take -es as in ‘hero/heroes’. Some irregular plural nouns are formed by changing ‘-oo’ to ‘-ee’ as in the amlaut plurals foot/feet and man/men but not *foots/mens’ notwithstanding the addition of the ‘-s’ ending to the regular nouns such as ‘pans’ and ‘pens’ (Rinvolucri, 1984), or ‘-a’ to ‘-en’, for example, ‘woman/ women’. Furthermore, some irregular singular nouns require a substantial amount of modification to the other forms such as ‘penny/pence’ in British usage where the 1 penny becomes ‘pennies’.

The irregular plural nouns from Latin and Greek change ‘-us’ to ‘-i’ in ‘radius/radii’ although ‘radiuses’ is acceptable. The Latin ‘alumnus’ [foster son] changes into ‘alumni’ in the second declension. However, in the first declension ‘-a’ bears a plural form ‘-ae’ in alumna [foster daughter] that becomes alumnae (Silver & Martins, 2012). The ending in ‘-um’ takes ‘-a’ as in curriculum/curricula. The ‘-ix’ in ‘appendix’, for example, takes ‘-ces’ and ‘-xes’ in ‘appendices’ or ‘appendixes’. Similarly, nouns ending in ‘-x’ in ‘index’ take similar form ‘indecis’ and ‘indexes’ whereas in ‘ox’ it takes a rather different form ‘-en’ to form ‘oxen’. In the Greek irregular nouns, the ending ‘-us’ takes ‘-es’ in octopus/octopuses’ while ‘is’ uses ‘-es’ in analysis/analyses but not ‘analysises’ and ‘axis/axes’ (also a plural of ‘axe’) but not ‘axises’. The ending ‘-ma’ takes ‘-ta’ in stigma/stigmata while ‘-on’ change to ‘-a’ in ‘criterion/criteria’. Nevertheless, in the English language both regular and irregular noun endings can be used in one sentence although their endings are different from one another, for example, ‘Wanga bought two pairs of shoes from three different women’ where ‘shoes’ is regular while ‘women’ is irregular.

The current research was underpinned by Martin Haspelmath (1996: 43) regarding the ‘Word-class-changing inflection and morphological theory’. This theory states that derivational affixes can change the word-class of their base, while inflection affixes do not. Haspelmath argues that this idea lost the important discernments about the nature of inflection and derivation because it does not recognise the word-class-changing inflection. The word-class-changing markers can be inflectional, and the property of being word-class-changing is different from the property of derivational morphology. Therefore, the derivational affixes and inflectional wordclass-inflection are extant, and they are transpositional derivational morphology because they can change the word-class of their base or word stem. The word-class-changing derivational affixes can change from one class to another, for example, adjectives can be changed to nouns, verbs to adjectives, verbs to nouns, nouns to verbs, nouns to nouns, and so forth. In addition, transpositional inflectional morphology on the irregular plural nouns can occur in word classes including nouns to nouns, nouns to adjectives, nouns to verbs, verbs to adjectives, verbs to nouns, and adjectives to adjectives.

Haspelmath (1996) regards the changing of adverbs to adjectives as ‘attributivizer’. Conversely, the changing of nouns to verbs is called ‘predicativiser’. Haspelmath, therefore, contends that the word-class changing exist. Also, Haspelmath advises that all linguists should be apprehensive that word-class exists in English since the belief that transpositional morphology is derivational and found everywhere in literature. The existence of the morphological inflection is indirect and implicit. The derivational affixes can transform the grammatical class by adding the derivational suffix ‘ful’ as in the noun ‘care’ to form the adjective ‘careful’. Therefore, the derivational and inflectional affix can change syntactic category of the word stem in the distribution of class membership and if t affixes are removed from the words, stems remain. Nielsen (2016) contends that the inflectional rules do not change word classes while derivation ones can, and that derivation rules transform the syntactic category of their base, whereas inflection rules do not. In this situation he is biased since irregular plural noun inflection can change word classes.

According to Haspelmath (1996:46) both inflection and derivation exists in English even though Drijkoningen (1994) argues that transpositional morphology of the irregular plural nouns mechanically belongs to derivation. However, it is inflectional if it determines the resulting word class. Haspelmath claims that this view is convincing although he used old terminologies instead of grammatical paradigms. His derivational formations are described by listing them individually

in a dictionary although grammar and dictionary are universal. They are inflectional, regular, general, and productive notwithstanding they are derivational, irregular, defective, and unproductive. Therefore, it is evident that the inflectional morphology of the irregular plural nouns exists. Haspelmath contends that structures of words can be described using abstract paradigms only if new words can be formed according to the rule, namely: ‘regular’ if words do not have any additional idiosyncratic properties. Besides, they are ‘general’ when all bases to which the rule could apply allow the formation of the word. Conversely, if a rule is unproductive, irregular, and defective, an abstract paradigm is not appropriate for the description, and each form must be listed individually in the dictionary.

An example given by Haspelmath shows that in a Germanic language, participles can be formed from any verb, they are maximally general, and their forms and meanings show almost no idiosyncrasies, and the meaning is regular and productive. The inflection and derivation are, therefore, not absolute but allow for gradience and fuzzy boundaries. Productivity, regularity, and generality are constituent properties, not two-fold, all-or-nothing features. The “inflection and derivation are prototypical inflection than prototypical derivation” (Haspelmath, 1996:47) and that inflection is a relevant morphology to syntax. He claims that the verb can be used as a modifier rather than argumentative. Thus, word classes are inflectional because they can change from one class to another.

Case (2019:12) asserts that learners “generally have much more trouble understanding and using the countable nouns like ‘people’ and ‘some sheep’ as well as uncountable ones like sand and hair, and often from very early in their language learning. The most common problems faced by learners regarding the irregular plural nouns, according to him, including not knowing that a word is irregular and so just adding an ‘-s’ as usual as in ‘Four *childs’ X, knowing that a word is irregular but not having memorised the right irregular form, not knowing if a form is singular or plural, for example, ‘*One media is…’ X, adding an ‘-s’ to irregular plurals to make a kind of double plural like ‘*The childrens…’ X, correcting themselves even when the regular plural is also okay or even more common than the irregular version and unnecessarily changing the sentence such as ‘*The curriculums…’ to ‘The curricula…’, matching an irregular plural without ‘-s’ with a singular verb due to thinking that an irregular plural is uncountable, for example, ‘*There is much sheep on the hills’ X, and only knowing the plural form particularly if it is more common as in ‘bacteria’ and ‘strata’. Further, the trickiest noun is ‘data’ pluralising ‘datum’ as on the face value it sounds like singular and uncountable noun although it is not, and increasingly acceptable in British English than American English taking the plural noun ‘data’. The “teaching irregular plural noun morphological inflection to learners can be a rather complex because they do not understand the existence” (Silver & Martins, 2012:20) of various irregular plural noun endings. According to Hoang (2021) different teachers might be using unfounded methodologies for teaching the English language. On this basis, it is a requirement for these teachers to develop innovative teaching strategies in this regard.

Vygotsky’s (1980) Social Constructivist Learning Theory addresses methods, concepts, and foundation principles in teaching and learning. It states that learning can be active within the social relationship paradigms as knowledge is socially constructed with or without the teachers’ guidance. He believes that that “individuals learn via social interactions with other individuals and that children learn best in an adult-child sociocultural environment” (Vygotsky, 1978:8). Also, he argues that learning becomes effective when the learners imitate their role models (Geiser, 2021). Nonetheless, this theory blends the teacher-guided and the student-centred priorities. Also, Isaacs (2018) maintains that ‘The Montessori Theory’ attests that learning occurs effectively with the use of games. According to Forbes (2021), in teaching and learning

the educational games related to multicultural competency have consistently been utilised such as ‘The Empathy Game’ used by Anderton and King (2016) to increase students’ empathic abilities and self-awareness. Educational game learning leads to creativity and innovative orientations (James & Nerantzi, 2019). Through educational games, learners enjoy and get motivated in learning since they can connect theory and practice as well as offer support to learning activities. In this regard, Blanton (2017) estimates that games entrench learning and educational theory without altering the game constructs. Thus, learners can practise discipline-specific competence in teaching and learning.

When the irregular plural noun morphological inflection becomes difficult for learners especially those who cannot follow any logical rules due to language delays, make a list of irregular plural nouns word pairs that are commonly used or pose serious challenges to learners. Decide on how to be present them. These nouns can be written on flashcards or index cards together with pictures available online or in a clipart. Initially, target at least 20 difficult words and then drill the morphological inflection of the irregular plural nouns, as in the consonant ‘f’ letter changing into ‘-ves’ than ‘-s’. A singular word can be mentioned and ask them to make sentences with the word pairs like ‘foot/feet’ that are repeated more than twice. Correct them during conversations by starting with at least 10% of the work and gradually and gently proceeding to more percentages like 90-100%. Then ‘Speech and Language Therapy Guide’ by Ms Carrie’s E-Book can be used to train them further. Correspondingly, the ‘Plurality for iPad' game can be used for advanced learners. The simplest way is to allow them to play or give up as they wish and consequently lose all the cards from that round if they make a mistake before they stick the longest string of correct answers during the game for a win. Learners win if they manage 12 cards in a row without making a mistake (Case, 2019). For perfect practice, cards can be placed in a column to represent a ladder and get learners to start from its bottom again every time a mistake is made. The non-native learners of English language are expected to be competent in the inflection of irregular plural nouns. This requires the teachers’ innovative strategies for counteracting any development of errors caused by poor competence in this regard.

Although there are different teaching strategies including ‘noughts and crosses’, ‘grammar tennis’, ‘Back-wiring’, ‘Odd one out’ and ‘Word search’, “games can be used to tackle irregular” (Rinvolucri, 1984) plural noun morphological inflection. As Forbes (2021) claims educational games are useful in teaching and learning irregular plural noun morphological inflection, various games including the irregular plurals reversi memory game or Othello like the Japanese ‘Go’ game (Verner, 2021), the irregular plural noun board game, the irregular plurals simplest responses game, the irregular plurals storytelling game, and ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ (Rinvolucri, 2002) can be used. However, in the current research the focus was on the following two games:

According to Verner (2021), “The game itself is simple, and it is easy to modify for use in class.” In this context, the game board was not even necessary since it just used simple playing cards to set up a game. Following Case’s (2019) suggested instructions, the researchers cut up one pack of cards per group of two to four learners, leaving the two halves of one card with the singular and plural still joined to each other. In the process, each square of the table was not cut out. Cards were given out and learners were asked to fold them so that one side had the singular and the other the plural. They were placed anywhere on the table as learners pleased. The researcher made sure that each pair of players had a flat surface to play on. One player was on the number side of the card while another was on the pattern. The researcher started with four cards on the table in a two-by-two grid alternating pattern and number sides. Players strategically placed cards so that more cards of their side showed at the end of the game. To turn cards to their side, a player placed one of the cards at the end of a row whose other end card matched their side.

Then all the cards were flipped in that row to show their side. This means that in a row of three cards, pattern-number-number, a player placed a pattern card at the opposite end and then turn all the cards to show the player’s side, pattern-pattern-pattern-pattern (Case, 2019). When the original row was number-pattern-number, the player of the pattern side was unable to play a card on that row. The researcher decided whether players could be allowed to play diagonal rows in their game. It was possible to play a card so that players could turn cards in more than one row. At the end of the game, the player with the most cards showing on their side won it. The cards were labelled with the target structure by writing the words on the cards. Some irregular plural nouns were printed on labels and then affixed to the playing cards. Players were instructed to choose a card and indicate what they thought was on the other side. They said ‘One…’, for example, with the singular version, and ‘Some…’ with the plural version to help them check. The players then turned the card over to check, leaving it the other way up. They continued doing this with other cards until they gave up or made a mistake. When a mistake was made before they gave up, they could not take any of the cards that they guessed correctly in that round and scored one point for each. All the correct cards stayed on the table for the next player to try the other way round as they were then upside down. The next player then did the same with cards that other players tried before, new ones that anyone had not tried yet, or probably a mix of both kinds. Each time, they could quit after just one card or theoretically continued until the whole table was cleared at once or they lost all the cards from that round after making a mistake.

After all the cards were taken, the game was stopped. The players wrote ‘one’ and ‘some’ on the right side of each card and tested one another orally using an ‘un-cut-up’ copy of the worksheets. When players had gained an understanding of the word pairs, they constructed sentences like ‘I saw one woman, but two women disappeared’. Sentences were repeated from the most common pairs to the complex, for example, ‘One octopus swam in the water when three octopuses chased a prey’. The researcher influenced learners to create paragraphs or held conversations. In contrast, when constructing sentences wrongly, for example, ‘There were many sheeps’ (Case, 2019) or ‘Many woman work can iron dresses’, they were corrected gradually and gently. In these sentences, the words ‘sheeps’ and ‘woman’ are ungrammatical. Likewise, learners were taught productive techniques such as ‘one datum, two data, three data’. However, the researcher dwelt on their existing knowledge to elicit the idea gained using the simple regular inflection and irregular plural presentation when mistakes are still made by learners. Some cards to cut up in the advanced/senior phase included irregular plural nouns such as innings, analysis, bacterium, species, spacecraft, mouse, ox, and automaton. Nevertheless, if irregular plurals reversi memory game was unproductive, the following game was utilised:

The researcher previously chose a dozen irregular plurals and got learners to push their chairs against the walls to form two parallel lines facing him and equidistant from the side walls of the room (Rinvolucri, 1984). One column was the ‘singular team’ and the other the ‘plural. The researcher shouted, for example, ‘mouse’ and a member of the singular team rushed to the wall, while someone from the other team tried to stop the player from getting there. When they managed to touch their classmates, then they joined their team. The game continued with more singular or plural forms of irregular nouns and the researcher lingered on the initial sound of the words, to build up excitement. The team that got to the end with more students won the game.

Based on the preceding discussion, the researcher aimed to examine the irregular plural noun morphological inflection by the Grade 8 learners at Nadedzo Secondary School as an attempt to answer the questions: 1) What types of teaching strategies can be used in the inflection of irregular plural nouns? (1) How the identified teaching strategies can be used in the inflection of irregular plural nouns? (3) What are the causes of poor competence in the inflection of irregular plural nouns?

The researchers utilised a Hermeneutic Interpretive Phenomenological (HIP) methodology. They envisaged understanding the meaning and the interpretation of the learners’ experiences in using a game approach (Creswell, 2014) and the other techniques relevant for teaching and learning the irregular plural nouns regarding the morphological inflection. The research adopted a quantitative design due to valid research outcomes (Abuhamda, Bsharat & Ismail, 2021) it provides based on mathematical calculations and statistics. The post-positivist arguments dealt with knowledge, cause-and-effect reasoning, reduction to individual variables, and theory tests using a questionnaire (Basias & Pollalis, 2018). Predetermined data collection emphasising quantification in data collection and analysis was used. The reality of the establishment and the variables were counted with numbers (Abuhamda et al, 2021). Also, integrity, trustworthiness, and authenticity concerning the correctness of the results were used. The probability sampling technique was used to examine the teaching of 15 Grade 8 participants who were randomly sampled as the research population at Ndaedzo Secondary School in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Therefore, the envisaged game strategies “steered the way of creating a socially constructed environment” (Forbes, 2021:59) that enable learning using experiences and reflection.

The collection of data was based on (1) the provision of a questionnaire, (2) participants’ choices from a set of pre-defined responses to the questionnaire, and (3) the natural setting of the questionnaire’s response “to provide backbone structure to researcher for planning of answering the research questions’ (Pawar, 2021). A list of subsequent themes with multiple choice answers typed in sequence and printed to draw data from the participants (Aryal, 2017). The closed-ended questions were used, and empirical data were classified using a coding technique. Learners’ answers were grouped according to the frequency of occurrence. Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins’ (2020) findings were used to entrench data authorisation using their internal reliability. In addition, the seriousness of the participants towards the questionnaire necessitated the reliability and trustworthiness of their competence that did not completely represent the consistent reliability (Mohajan, 2017). The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22 was used in the interpretations of data. The research was conducted within the rules and regulations of the University of Venda ethical guidelines. The participants were informed about the purpose of

the research, their safety, anonymity and confidentiality, absence of remuneration as well as data storage before the research was conducted.

As the research aimed at examining the English L2 strategies for teaching irregular plural noun morphological inflection, eventually data reduction was invaluable for sorting, selecting, classifying, and eliminating irrelevant data against the focus of the research. Nevertheless, relevant data were interpreted and presented according to the research aim. The conclusion was based on the depiction of the research findings, verification of data, specification, and validation of the results. The next questionnaires dealt with the envisage innovative strategies.

Table 1: Irregular plural nouns reversi memory game

Questions Participants’ responses

|

Correct |

Incorrect | |

|

responses |

responses | |

|

1) Two (spacecraft/ spacecrafts) disappeared into the sky |

85.8% |

14.2% |

|

2) An (automata/automaton) is a self-propelled machine |

88.7% |

11.3% |

|

3) (Data/datum) are usually collected in research |

91.9% |

8.1% |

|

4) Uncle bought three (oxens/oxen) last week. |

94.0% |

6.0% |

|

5) She made more (analyses/analysis) of Covid-19 |

79.6% |

20.4% |

pandemic

Although the morphological inflection of irregular plural nouns is challenging to the English L2, it was evident that after using the irregular plural nouns reversi memory game strategy, learners performed extraordinarily. For example, 85.8% of the participants in question 1 were competent. They could select the answer ‘spacecraft’ which was in line with the objective of this research paper. The participants knew that the irregular noun 'spacecraft' requires plural zero-inflection. Additionally, they knew that the addition of an ‘-s’ to ‘spacecraft’ is not consistent with the formation of irregular nouns. This discovery supports Forbes’ (2021) suggestion that educational games are useful in teaching irregular plural nouns. However, the minority (14.2%) were incompetent as they selected the noun ‘spacecraft’ as their correct answer. They might have been confused by the rule regarding the regular noun inflection. This rule states that the ‘-s’ or ‘-es’ ending is added to the stem of regular nouns during pluralisation. This finding is in line with Case’s (2019) claim that learners are troubled with the inflection of irregular nouns.

Question 2 shows that the majority (87.7%) of the participants mastered the morphological inflection of irregular plural nouns as they selected the answer ‘automaton’ although it was used vis-à-vis the topic of the research. They knew that the irregular noun ‘automata’ is plural while ‘automaton’ is singular. Since the nature of the question ‘An (automata/automaton) is a selfpropelled machine’ is in a singular form requiring a singular answer ‘automaton’, the participants did not find any difficulty. Similarly, this detection is congruent with Forbes’ (2021) suggestion

that educational games are useful in the teaching of irregular plural nouns. Contrarily, the minority (11.1%) of the participants were incompetent as they selected the answer ‘automata’ hoping that it might be singular. They did not know that the irregular nouns can be pluralised by adding a suffix ‘-a’. This outcome is in line with Conway’s (1998) claim that to correctly inflect the individual words of a sentence to reflect their number, person, mood, or case is a complex matter.

It was evident from question 3 that after utilising this game, the majority (91.9%) were competent in the irregular plural noun morphological inflection. They knew that the irregular noun ‘data’ is in the plural form and selected it for an answer than ‘datum’ which was in the singular form. Anyhow, they might have dissected the question further and realised that the presence of the main verb ‘are’ requires the plural noun for consistency purposes. The discovery is congruent with Case’s (2019) claim that learners find it easy to pluralise the irregular nouns if the irregular plural noun reversi memory game is used. However, the minority (9.1%) of the participants were incompetent because they selected the singular noun ‘datum’ which was not in line with the form of a question. The participants were puzzled by the difference between the irregular nouns ‘data’ and ‘datum’. They might have judged the nouns according to their length and thought that since ‘datum’ is longer than ‘data’ it might be a correct answer. Further, they lacked competence in the use of the plural verb ‘are’ because they would have selected the answer ‘data’. The outcome is in contrast with Nordquist’s (2020) suggestion that games are useful in the teaching of irregular plural nouns.

Question 4 strongly supported the idea that the irregular plural noun reversi memory game is important to eliminate difficulties face the English L2 learners because a large number (94.0%) of the participants selected the answer ‘oxen’. They were never confused by the addition of an ‘-s’ ending to the ungrammatical word ‘oxens’ they knew that the suffix ‘-en’ can be added to the irregular nouns to make them plural. This discovery is in line with Forbes (2021) who suggests that educational games are useful in teaching irregular plural nouns. Nonetheless, only 6.0% of the participants were incompetent in the use of the irregular plural noun morphological inflection. They elected the answer ‘oxens’ which is nowhere in the English dictionary. They might have been confused by the rule on the formation of the regular plural nouns. This rule states that the suffix ‘-s’ can be used in the pluralisation of irregular nouns. Correspondingly, they ignored the inflection of the suffix ‘-en’ to the stem of the singular nouns during their pluralisation. This result is congruent with Case’s (2019) suggestion that sometimes the English L2 learners are challenged by the inflection of irregular nouns.

Even question 5 shows that the majority (79.6%) of the participants were competent in the inflection of the irregular nouns because they selected the irregular plural nouns ‘analyses’. They understood the difference between the noun ‘analyses’ and ‘analysis’. They knew that the irregular noun ‘analysis’ could be turned into plural form by changing the vowel ‘-i’ for ‘-e’. The use of the adjective 'more' in this question indicated that they were dealing with the plural noun forms. The finding supports Forbes (2021) who suggests that games are useful in the learning of the irregular plural noun morphological inflection. Conversely, 20.4% of the participants did not perform well in this question. They chose the answer ‘analysis’ regardless of the presence of the word ‘more’ which gave them a hint to the plurality of the analysis made. Moreover, they could not show their competence in the changes occurring in vowels ‘-i’ and ‘-e’. This outcome is congruent with Conway’s (1998) suggestion that English automatically generating correct English is fraught with difficulty. Nevertheless, although it is worrisome that 20.4% of the participants did not perform better, in this questionnaire, most participants performed exceptionally using the irregular plural nouns reversi memory game strategy. Thus, the indispensability of this game can likewise be noted in the following graph:

He has two (womens/women) and four (sheep/sheeps).

100

90

80

70

<υ

≡ 60

ΠJ φ

'o 50

<u

f 40

3

30

20

10

0

96%

88%

24

Women

23

4%

1

Womens Sheep

Learners responses

12%

3

Sheeps

■ Frequency ■ Percent

Figure 1: Irregular plural nouns in movement game

In this figure, the majority (24 amounting to 96% and 22 to 88%) participants were competent

in the irregular plural noun morphological inflection because they could select the correct irregular plural nouns ‘women’ and ‘sheep’. The participants knew that irregular countable nouns can be formed using various ways. Similarly, they knew the noun ‘woman’ does not require the addition of an ‘-s’ since vowel ‘-e’ can replace ‘-a’ during the pluralisation procedure to form ‘women’. For example, the noun ‘sheep’ does not need the suffix ‘-s’ because it is pluralised by using the zero-inflection process. This discovery is in line with Nordquist’s (2020) suggestion that the ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ in the teaching of irregular plural nouns. Conversely, only 1 participant amounting to 4% and 3 to 12% were incompetent. They selected the ungrammatical answers ‘womens’ and ‘sheeps’ as they might have been confused by the rule regarding the inflection of regular nouns. The finding is congruent with Silver and Martins’ (2012) suggestion that irregular plural nouns causes difficulties to learners. This rule states that

when the regular nouns are changed from singular to plural forms the ‘-s’ or ‘-es’ ending is

morphed to the nouns. Further, they disregarded the rule regarding the substitution of the ‘-a’ vowel in favour of ‘-e’ and the zero-modification (Wall Street English, 2022) of some irregular nouns. Also, the ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ is an excellent strategy for teaching in this regard.

From the study findings established using questionnaires for examining English L2 learners’ competence in the irregular plural noun morphological inflection, the fundamental conclusions are (1) the identifying the profound innovative strategies for teaching this inflection and for addressing the difficulties faced by learners, (2) understanding that the proficiency of teaching the inflection in this essence, (3) understating that the ‘irregular plural nouns reversi memory game’ and the ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ strategies are ground-breaking and relevant in the learning of English. In both questionnaires, the effectiveness of the two identified strategies enabled learners to perform outstandingly even though there were some poor competencies established by the researcher. Nevertheless, that was quite natural to come across such encounters in any learning environment. The discoveries in this research paper are in line with the objective of the research, namely: to examine the innovative strategies for teaching irregular plural noun morphological inflection to non-native learners. Therefore, the identification of the strategies useful in the teaching of the irregular plural noun, in this situation, guaranteed the proper communication in both the academic and the social epitomes. In conformity with the conclusions mentioned in the preceding paragraph of the current research, the next suggestions are (1) workshopping teachers regularly in the innovative teaching strategies such as the ‘irregular plural nouns reversi memory game’ and ‘irregular plural nouns in movement game’ useful for teaching the irregular plural noun morphological inflection, (2) exposing learners to practice this inflection, (3) inspiring researchers to conduct further studies on the formation of the irregular plural nouns (4) integrating the game strategies in the teaching of irregular plural nouns in the school syllabus and (5) encouraging the curriculum developers to incorporate these strategies in their curricular.

References

Abuhamda, E., Bsharat, T. R. A. & Ismail, I. A. (2021). Understanding quantitative and qualitative research methods: A theoretical perspective of young researchers. International Journal of Research, 8(2), 71-87.

Anderton, C. L. & King, E. M. (2016). Promoting multicultural literacies through game-based embodiment: A case study of counsellor education students and the role-playing game oblivion. On the Horizon, 24(1), 44-45.

Aryal. S. (2019). Questionnaire method of data collection. Microbe notes. Available online at: https://microbenotes.com/questionnaire-method-of-data-collection/[Accessed on 8 September 2021].

Audring, J. & Masini, F. (2018). Introduction: Theory and theories in morphology. The Oxford handbook of morphological theory. Oxford University

Press.DOI:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199668984.013.1

Basias, N. & Pollalis, Y. (2018). Quantitative and qualitative research in business & technology: Justifying a suitable research methodology. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 7, pp. 91-105.

Blanton, E. G. (2017). Real-time data as an instructional tool: examining engagement and comprehension (PhD Thesis). Lynchburg, VA 24515, USA: Liberty University.

Case, A. (2019). How to teach irregular plurals. Online available at: https://www.usingenglish.com/teachers/articles/how-to-teach-irregular-plurals.html[Accessed on 22 January 2022].

Conway, D. (1998). An algorithmic approach to English pluralization. In proceedings of Second Annual Perl. Online available at: http://www.csse.monash.edu.au/~damian[Accessed on 20 January 2022].

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Drijkoningen, F. (1994). Affixation and Logical Form. Linguistics in the Netherlands, 11(1), pp.25-36.

Forbes, L. K. (2021). The process of play in learning in higher education: A phenomenological study. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 57-73.

Geiser, M. S. (2021) Comparing Techniques for Teaching Middle School Science Students to Decode Complex Words Based on Morphology: A Causal Comparative Study. [PhD Dissertation - Northcentral University, California].

Haspelmath, M. (1996).Word-class changing inflection and morphological

theory.Yearbook of morphology 1995, edited by Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Kluwer, pp.43-66.

Hoang, V. Q. (2021). The differences of individual learners in Second Language Acquisition. International Journal of TESOL & Education, 1(1), 38–46.

James, A. & Nerantzi, C. (2019). The power of play in higher education: Creativity in tertiary learning. Palgrave Macmillan. Journal of Teaching and Learning 15(1), p1.

Jurafksy & Martin. (2017). Morphology: Word formation, FSAs and FSTs. Online available at:https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~jcheung/teaching/fall-2017/comp550/lectures/lecture2.pdf[Accessed on 17 January 2022].

Isaacs, B. (2018). Understanding the Montessori approach (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Khan, S. I. (2020). Parts of speech. Available online at: www.literaryenglish.com [Accessed on 6 August 2021].

Leithwood, K., Harris, A. & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5-22.

Mendívil-Giró, J.L. (2021). Inflection, derivation and compounding: Issues of delimitation. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish Morphology. Routledge. pp. 55-67.

Merriam-Webster (2021). Noun. Online available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com › dictionary › noun [Accessed on 6 January 2022].

Mohajan, H. K. (2017). Two criteria for good measurements in research: Validity and reliability. UTC Annals of Spiru Haret University, 17(3), 58-82.

Naser, M. (2017). The use of irregular cases by the English and literature students at the University of Tabuk. British Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 103, 16 (2), 102110.

Nielsen, P.J. (2016). Inflection and derivation. In Functional Structure in Morphology and the case of non-finite verbs. Brill. pp. 258-289.

Nordquist, R. (2019). 100 irregular plural nouns in English. Online available

at:https://www.thoughtco.com/irregular-plural-nouns-in-english-1692634[Accessed on 22 January 2022].

Nordquist, R. (2020) The 9 parts of speech: Definitions and examples. Online available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/part-of-speech-english-grammar-1691590 [Accessed on 22 January 2022].

Pawar, N. (2021). Type of research and type research design. Social research methodology (An overview), pp. 44–57.

Rinvolucri, M. (1984). Grammar Games: Cognitive, affective and drama activities for EFL students. Cambridge: C.U.P.

Schlechtweg, M. & Corbett, G. G. (2021). The duration of word-final -s in English: A comparison of regular-plural and pluralia-tantum nouns. Morphology, pp.1-25.

Silver, E. M. & Martins, C. S. N. (2012). Irregular plurals: an ingenious way of teaching grammar. EDUSER: revista de educacao, 4(2), 12-29.

The Albert Team (2021). Irregular nouns: Definition, examples, & exercises. Online available at https://www.albert.io/blog/irregular-nouns/[Accessed on 29 January 2022].

Tree Valley Academy. (2021). Printable plural nouns worksheets for kids. Online available at: http://www.treevalleyacademy.com[Accessed on 11January 2022].

Verner, S. (2021). 10 fun ways to use Reversi to teach grammar. Online available at:

https://busyteacher.org[Accessed on 15 January 2022].

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the development of children, 23(3),34-41.

Wall Street English (2022). Irregular plural noun. Online available at: https://www.wallstreetenglish.com/exercises/irregular-plural-nouns[Accessed on 22 January 202]

Biography of Author

Farisani Thomas Nephawe is an instructor of English Communication Skills (ECS) in the Department of English, Media Studies and Linguistics at the University of Venda (Univen), Limpopo Province, South Africa. He is currently a coordinator of Community Engagement, Linkages and Partnerships at the same university. He earned his MPhil in Second Language Studies at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa, and PhD in English at Univen. His scholarly interests include English Language Teaching, Pragmatics, and Communication skills.

Discussion and feedback