Social Pragmatic Failure of Indonesian Mandarin Learners at Elementary Level

on

e-Journal of Linguistics

Available online at https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eol/index

Vol. 15, No. 2 July 2021, pages: 162-170

Print ISSN: 2541-5514 Online ISSN: 2442-7586

https://doi.org/10.24843/e-jl.2021.v15.i02.p02

Social Pragmatic Failure of Indonesian Mandarin Learners at Elementary Level

-

1 Liu Dan Dan Nanchang Normal University, China Email:yf4248203@163.com

-

2 I Made Suastra Department of Linguistic, Faculty of Arts, Udayana University, Indonesia, Email: madesuastra@yahoo.com

-

3 Elvira Septevany Department of Tourism, Politeknik Negeri Bali, Indonesia, Email: elvira_s@pnb.ac.id

Article info

Received Date: 15 March 2021

Accepted Date: 22 April 2021

Published Date: 31 July 2021

Keywords:*

Social pragmatic failure, Mandarin language, Indonesian learners, elementary stage

Abstract*

The aim of this study is to help Indonesian learners avoid the failure of social pragmatics in intercultural communication and achieve successful communication goals. The data collection technique was carried out in two ways, the one way was done by distributing questionnaires given by google form, and the other way was done by direct observation when the author had daily conversations with Indonesian learners which were followed up with orthographic recording and note-taking techniques. The sampling technique was carried out by purposive sampling. The samples used were students at the elementary level learning Mandarin at Universitas Hasanuddin and Sekolah Islam Athirah of Indonesia. Through analyze, the results of the usage of Mandarin with a contextual approach, we find that there are 4 main types of social pragmatic failures committed by Indonesian learners at their elementary stage. These four types social pragmatic failures consist of failure to address people, failure to greeting, failure to farewell, and failure to ask for permission.

Cross cultural communication occurs in the native-non-native interactions and any communication between two people who, in any particular domain, do not share a common linguistic or cultural background. If a second language learner wants to be proficient in a foreign language, he must pay attention to the cultivation of pragmatic competence. According to Thomas (1983) pragmatic competence is the ability to use language effectively to achieve certain goals and understand language in context. Liu (2002) believes that pragmatic competence refers to the ability of listeners to understand the meaning and intention of others and to accurately express their own meaning and intention on the basis of their knowledge of context.

The lack of pragmatic competence of L2 students can lead to pragmatic failure. Pragmatic failure refers to the failure to correctly understand the speaker’s intention, which eventually leads to communication failure. They can be divided into pragmalinguistic failure and sociopragmatic failure (Thomas, 1983).

Pragmalinguistic failure, which occurs when the pragmatic force mapped by S(speaker) onto a given utterance is systematically different from the force most frequently assigned to it by native speakers of the target language, or when speech act strategies are inappropriately transferred from L1 to L2, and sociopragmatic failure, a term which refer to the social conditions placed on language in use. In other words, pragmalinguistic failure is basically a linguistic problem, caused by differences in the linguistic encoding of pragmatic force, while sociopragmatic failure stems from cross-culturally different perceptions of what costitutes appropriate linguistic behaviour.

However, in the process of learning Chinese, due to various reasons, various pragmatic errors often appear, which affect the furthermore improvement of language learning. (He,2020) The social pragmatic failure occurs in the process of cross-cultural communication, based on common daily life (Zhao,2017). Many studies have shown that a wealth of language knowledge does not necessarily ensure proper language use, and the acceptability of grammar does not equal the acceptability of pragmatics(Dong,2010). The result of research conducted by Chen (2011) shows that there is about 41% pragmatic failure which occurs in using Mandarin auxiliary verb “了le” in the context. L2 teachers often ignore pragmatics, because of teaching difficulties, and instead focus on the grammatical aspects of the language (Amaya, 2008).

The social pragmatic failures need to be calculated, analyzed more deeply in order to reduce or avoid pragmatic failures. This article focus on the social pragmatic failures of Indonesian Mandarin learners at their elementary level, it is hoped that this research will arouse mandarin teachers’ attention to the social pragmatic failure.

There are two data collection techniques which involved in this study, the first one is questionnaire in google form, the second one is direct observation which conducted daily conversations with learners in the process teaching Chinese in Indonesia These conversations are recorded and organized into written materials. The sampling technique is carried out by purposive sampling, namely the sampling technique for data sources with certain considerations (Sugiyono, 2010). The data collection of this research is in accordance with the sociolinguistic research method by taking into account the context of language use. The students of elementary stage of learning Mandarin at Hasanuddin University and Athirah Islam School are selected as the sample in this research. The failure of Mandarin are analyzed using a contextual approach. The contextual approach is a learning concepts that help teachers connect between material ones taught to students' real world situations and encourage students to create the relationship between the knowledge it has and its application in their life as family and community members. (Nurhadi, 2002).

Indonesian learners often fail to implement Mandarin when they learn Mandarin as a foreign/ second language, especially for learners at elementary level. After daily observation and ask the learners with questionnaire, we find that there are four types of expressive social pragmatic failures in usage of Mandarin, such as failures to address person (称呼偏误 chēnghu piān wù), failures to greeting (招呼语偏误 zhāohū yǔ piān wù), failure to farewell (道别偏误 dàobié piān wù), and failures to ask for permission (请求偏误 qǐngqiú piān wù).

chēng hu piān wù

In interpersonal communication, choosing the right and proper address reflects one's own upbringing, the degree of respect for each other, and even the degree of the development of the relationship between the two sides and social customs. Therefore, it should not be used indiscriminately. Sun & Niu (2014) state that ”In the exchanges with foreign students, we found that their Chinese address terms, especially social address terms, are used in a very innocent way, and there are many problems.”

In the Indonesian environment there are several ways of addressing the person. If we do not know someone's name, we can call “nona (miss)” for a young lady, call “ibu (mam)” for a woman, call “bapak (sir)” for a man. However, it is easier to call someone if the position of the person is known, for example “dok (doctor)”, “bu guru (teacher)” or “pak guru (teacher)”. This kind of addressing also applies to Chinese environment. However, there is difference to addressing the person when the someone’s position is added with his family name, as in the example of Table 1.

Table 1. Addressing person in Mandarin and Indonesian

|

Chinese environment Title/Position+family name |

Indonesian environment Name (Family nama)+ Title/Position |

|

Liu 老师 |

Dosen Liu |

|

Zhang 教授 |

Professor Zhang |

|

Wang 医生 |

Dokter Wang |

|

Li 经理 |

Manager Li |

The examples above show that there are differences in addressing the person in Indonesian and Mandarin environment. In the Indonesian environment, the way to addressing someone can be stated with the position first and then followed by the person's name or family name. On the other hand, in Mandarin environment, the way to addressing someone can be stated with his family name first, and then followed by his position/title.

At the beginning of the Mandarin language learning, because of the interference of mother tougne, the failures of addressing teachers often produced by Indonesian learners, they usually wrongly address “Liu laoshi” to “laoshi Liu”, or address “Dandan laoshi” to “laoshi Dandan”. Although been corrected several times by teachers, Indonesian students are still going to go wrong when address their teachers.

The reason for this failure is that the positions of the central words and modifiers in Mandarin and Indonesian are different. In Chinese, the central word is in the behind and the modifier is in the front, while in Indonesian, the central word is in the front and the modifier is in the behind. In the other word, the focus of an Indonesian sentence is in the front, and the focus of a Mandarin sentence is in the behind. So, the addressing term always fails to apply especially to Indonesian students at the elementary stage. They always reverse the position of someone’s name

or family name with their title, for example laoshi Liu, jiaoshou Zhang, yisheng Wang, and jingli Li.

zhao hu pia nwu

Greeting words exist in every language, and each language maybe has a different way of greeting. For example, “Hello”, “Hi”, and “How are you?” are used to express greetings between the English, “Halo” or “Apa kabar?” are used to express greetings between the Indonesian, “Assalamu Alaikum” is used to express greetings between the Arabs, and “Om Swastyastu” is used to the greetings between the Hindus in Indonesia. nι hao nfnhao nfnhao ma

There are many kinds of greeting words in Mandarin, such as “你好”, “您好”, “您好吗”, qu na er chτ le ma

“去哪儿? ”, “吃了吗?”. The pragmatic function of these greetings is different depending on the situation. “你好” is a greeting which usually used at the first time when you meet an unknown nǐ hǎo

person. “你好” is a greeting which used for those who are more respected, who are older or have higher social status. “你好吗?” is a greeting which used for friends who are already familiar but qu na er

in situations that have not been met in a long time. “去哪儿?” is a greeting used among chτ le ma

acquaintances when seeing him walking. “吃了吗” is the greeting used in the period of time before and after eating.

Indonesian students often use the above greetings incorrectly, especially at the elementary nǐ hǎ o stage. For example, the first time they meet the Chinese, Indonesian students directly use “你好 ma nǐ hǎo nǐ men hǎ o

吗?” instead of using “你好”;When the Chinese teacher asks all the students “你们好!” in class, most ha o l a os h τha o n Fnha o

students answer with “好” instead of “老师好!” or “您好”.

Figure 1 below shows that out of 49 students, there are 25 students who answered correctly, 23 students who answered incorrectly, and 1 student who did not know how to use it. This data nǐ hǎo ma shows that 50% of Indonesian learners have understood the use of the greeting words “你好吗?”. However, 23 students who answered incorrectly. There are many reasons for this kind of social pragmatic failure. The first one is the teaching materials that do not introduce the pragmatic rules of “how are you?”, besides that it was also caused by the teaching method. Teachers usually use the translation method so that forgot to tell the students the context of its use.

“ni hao ma? apa kabar?” Iebih cocok digunakan pada konteks apa?

.: Seriesl 8 25 IS 1

Figure 1. Questionnaire result

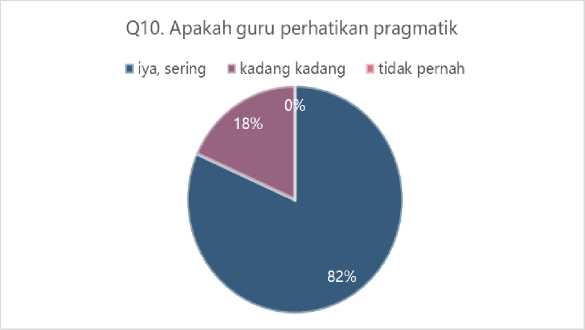

Instead, survey data shows that there are 25 students who answer correctly. The success of using the social pragmatic terms can be traced form teachers. In the question of “how often your teachers pay attention to pragmatic?”.

For the function of teachers, we ask the learners “When teaching a language item, does your teacher often explain how to use and what situation is more appropriate to use that sentence?”. The result shows that 82% of teachers often teach the pragmatic rules of a sentence.

Figure 2. Questionnaire value of teacher pay attention about pragmatic

According to He Ying (2020), there are three reasons for pragmatic mistakes: culture, knowledge and negative transfer from mother tongue. Pragmatic failures usually appear in the process of using Language. In general, language use needs a particular cultural environment, and it's not easy to understand. Because each country has a unique culture, a different language and the rules of communication, so when learning a second language or a foreign language, students find it very difficult to master the pragmatic rules and change their inherent thinking habits in communication.

The failure of this farewell is often expressed by Indonesian learners especially at the basic lǎo shī wǒ xiān qù le

level. The most commonly spoken phrase is “*老师 我 先 去 了” (Teacher, I will go first).

|

laosh∣ 老师 |

wǒ 我 |

xia n 先 |

qu 去 |

le 了 |

|

Guru |

saya |

duluan |

pergi |

(partikel) |

laosh∣ wo xian qu le

The expression *老师 我 先 去 了 is often pronounced by Indonesian learners when separating qù

from their teacher. In this context, the use of the verb “去” is not suitable. It should be more zǒu zǒu

appropriate to use the verb “走” because “走” in Mandarin means “going” and used in saying zǒu

goodbye with people and the word “走” emphasizes the meaning of “leave” a place. Its purpose is

qu

not clear. Whereas “去” in Mandarin means “to go to-”, usually followed by a place, the word qù

-

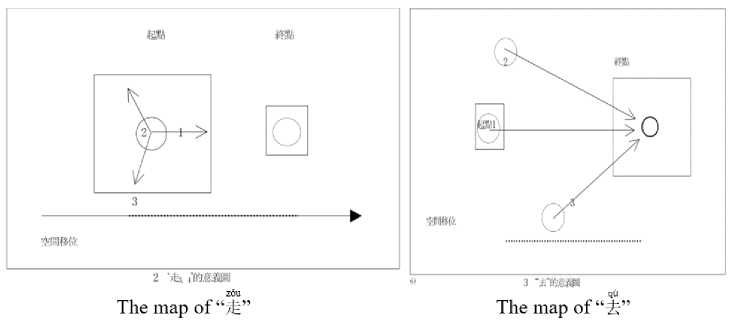

“去” emphasizes more “purpose”. It can be seen in Figure 3 below.

zǒu qù

Figure 3. Map of 走 and 去

zou qu zou

The picture above shows the use of the verbs “走” and “去”. The verb “走” is used when the qu

speaker plans to leave from somewhere while the verb “去” is used when the speaker plans to go somewhere. Another example is the following:

ta ga ng zo u

-

1. 他刚走。He's just leaving. wo mfngtia n ya o zou le

-

2. 我明天要走了。Tomorrow I'm leaving. ta qu be ijτng le

-

3. 他去北京了。He went to Beijing. nι ya o qu na r

-

4. 你要去哪儿?Where are you going?

Most of the pragmatic failures are due to negative transfer of the mother tongue. zou qu

Translation in textbooks sometimes confuses learners. The verbs “走” and “去” are usually the same translated into English as “go” or Indonesian as “pergi”. Meanwhile, in KBBI, the verb “go” has three meanings, namely:

-

(1) walking (moving) forward: he goes to the bathroom; he goes to the market.

-

(2) leave (somewhere): he has already left here.

-

(3) and departs: having locked the door of the house, he goes to his workplace; at five in the morning he went to the station. (KBBI)

zǒu

Here, the meaning of (1) is equal to (3) refers to the verb “走” in Mandarin. Guru or qu

teacher cannot translate the verb “去” in a simple way. So the connotation and denotation in the target language of the same mother tongue is different from a verb also causes learner pragmatic errors at the beginning of the second language learning process.

qIngqiu pia n wu

In this section, the failure to ask permission is also often encountered by Indonesian learners, especially at the basic level. For example, when Indonesian learners ask permission to their teachers because they cannot follow the lessons as usual.

lǎo shī míngtiān nǐ lái shàng kè ma

-

1. 老师 :明天你来上课吗?

xuéshēng lǎo shī wǒ bú huì míngtiān wǒ yāo qù yī yuàn

-

*学生 :老师,我不会,明天我要去医院。

It should be

laoshτ m^ngtia n n∣ la i sha ngke ma

老师 :明天你来上课 吗?

xue she ng laoshτ duι bu ql wo bu ne ngla i m^ngtia n wo ya o qu yT yua n

学生 :老师,对不起,我不能来,明天我要去医院。

|

m^ngtia n 明天 |

nǐ 你 |

la i 来 |

sha ngke 上课 |

shang ke 课 | ||

|

besok |

anda |

datang |

belajar |

kah? | ||

|

laoshτ 老师 |

duι bu q∣ wo bu nengla i 对不起,我不能来 |

m^ngtia n 明天 |

wǒ 我 |

ya o 要。 |

¾ |

yτ yuan 医院 |

|

Guru |

mohon maaf |

besok |

saya |

mau |

pergi |

rumah sakit |

laosh∣ nT j∣ntian ya o la i ma

2. 老师 : 你今天要来吗?

xue she ng la oshτ wo jτntia n bu huι la i wo youshι er

*学生 :老师,我今天不会来,我有事儿。

It should be

laoshτ n∣ jτntia n ya o la i ma

老师 : 你今天要来吗?

xue she ng lao shτ bu hao yι sτ wo jτn tia n bu ne ngla i wo you shι er

学生 :老师,不好意思,我今天不能来,我有事儿。

|

nǐ 你 |

j τn tia n 今天 |

ya o 要 |

la i 来 |

ma 吗? | |||||

|

besok |

anda |

datang |

belajar |

kah? | |||||

|

lao shτ 老师 |

bu hao yι sτ 不好意思, |

wǒ 我 |

jτntia n 今天 |

bu 不 |

ne ng 能 |

la i 来, |

wǒ 我 |

yǒu 有。 |

shι er |

|

Guru |

mohon maaf |

saya |

hari ini |

tidak |

dapat |

datang |

saya |

ada |

urusan. |

The same conversation of (1) and (2), both asked the teacher for permission, but the two did bu hao yι sτ

not use the word “不好意思 sorry”. In Chinese culture, teachers are so respected by society that a student and a student’s parents must respect their teacher and hear the teacher’s orders. In a campus or school environment, the words of the teacher are most listened to. At the time of requesting permission must apologize first then submit a request for permission. Indonesian learners who have first learned Mandarin and do not yet understand Chinese culture in terms of asking permission will directly ask permission without expressing an apology in advance. In addition, example (2) above shows the misuse of the auxiliary word “会”. The auxiliary word

huι bu ne ng bu ne ng

“会” should be changed to the auxiliary word “不能”. The auxiliary word “不能” is used when a person has the ability to do so but is unable to do so due to several factors (objective factors). bu huι

Meanwhile, the auxiliary word “不会” is used when someone doesn't know how to do it. “To the hospital” and “have business” are two reasons that are included in the objective factor, so it bu ne ng bu huι

should use the auxiliary word “不能” instead of the auxiliary word “ 不会”. Indonesian learners only know that these two phrases can be used but do not yet understand the context of their use.

4. Conclusion

Due to the interference of their mother tongue and the lack of mastery of mandarin pragmatic rules, Indonesian students who have just learned mandarin have appeared a lot of social pragmatic failures. Social pragmatic failures of Indonesian mandarin learners at their elementary level can be seen from the failures to address the person in mandarin, failures to greeting in mandarin, failures to say goodbye in mandarin, and failures to ask for permission in mandarin. The emergence of social pragmatic failures is a common phenomenon that will accompany the whole process of mandarin language acquisition. Mandarin language teachers and students need to work together in the learning process to reduce the pragmatic failures step by step and gradually improve the students’ mandarin level.

References:

Amaya, L. F. (2008). Teaching culture: Is it possible to avoid pragmatic failure?. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 21, 11-24.

Ai Feng, Chen. (2011). 印尼学生使用 “了” 的偏误及教学对策 ——从句法、语义、语用三个平面切入 Analysis of errors made by Indonesia learners in using “le” and suggestions of teaching methods-from the perspectives of syntax, semantics and pragmatics. Journal Of Zhaoqing University, 32(3), 32-35.

He, Ying.(2020).巴基斯坦留学生汉语学习的语用偏误分析[J]An Analysis of Pragmatic Errors in Learning Chinese by Pakistani Students.Journal of Kunming Metallurgy College,36(04):83-86.

Liu, S. Z. (2002). Pragmalinguistic failures and social pragmatic failures: One of the series of studies on pragmatic failures. Journal of Guangxi Normal University, 1(1), 44-48.

Nurhadi. (2002). Pendekatan kontekstual, Jakarta : Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, Dirjendikdasmen.

Pengfei, Zhao.(2017). 浅析跨文化交际中的社交语用偏误 Analysis of Social Pragmatic Errors in Intercultural Communication. Anhui Wenxue, 409, 82-83.

Qing, S. Y., & Xia, N. (2014). 在穗外国留学生称呼语研究 A Study on the address of foreign students in Guangzhou.语言文字应用 Application of Language,01, 120-127.

Sugiyono. (2010). Metode Penelitian Pendidikan (Pendekatan kuantitatif, Kualitatif dan R & D). Bandung: Alfabeta, 128.

Thomas, J. (1983). Cross-cultural Pragmatic Failure. Applied Linguistics, 20(2) 91-112.

Yuwen, Dong (2010).对外汉语教学视野下的汉语语用研究[J]The Study of Chinese Pragmatics from the

Perspective of Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Languagee.International Journal of Chinese,1(00):199-204.

Biography of Authors

Liu Dan Dan is a Doctor candidate of Linguistics in Udayana University, Denpasar, Indonesia. She was born in Henan, China, in 1982. By 2006, she finished her Bachelor Degree from Zhengzhou University, major in Chinese Language and Culture. In 2010 she got her Master Degree from the same university, major in Comparative Literature and World Literature. At the same year, she studied Master again in Hasannudin University, majoring Indonesian Language and Literature, and finished by 2015. After that, she continued to Doctoral study program of Linguistics in Udayana University, Denpasar, Indonesia. Now she works in the International Cooperation and Exchange Center of Nanchang Normal University, China.

Email: yf4248203@163.com

Prof. Drs. I Made Suastra is senior lecturer at faculty of arts, undergraduate Udayana University from 1993 until now.

Email: made_suastra@unud.ac.id

Elvira Septevany was born in Makassar, Indonesia, in 1989. She studied in Nanchang University, China, majoring in linguistic and applied linguistic from 2015 to 2018 . Now she is a lecturer in Tourism department, Politeknik Negeri Bali,Indonesia.

Email: elvira_s@pnb.ac.id

Discussion and feedback