Cross-Gender Inovativeness of Using Code Switching in Indonesan TV Talk Show

on

e-Journal of Linguistics

Available online at https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eol/index

Vol. 14, No. 1, January 2020, pages: 57-70

Print ISSN: 2541-5514 Online ISSN: 2442-7586

https://doi.org/10.24843/e-jl.2020.v14.i01.p07

Cross-Gender Inovativeness of Using Code Switching in Indonesan TV Talk Show

1Luh Putu Laksminy Denpasar, Indonesia putu_laksminy@unud.ac.id

Article info

Received Date: Nov 06, 2019

Accepted Date: Nov 09, 2019

Published Date: Jan 31, 2020

Keywords:*

implication, speaker, television programs.

Abstract*

Speakers will usually choose the appropriate code (certain languages, dialects, or variations of the same language) when communicating. The use of code switching by inserting English words, phrases, sentences, or clauses into Indonesian utterances is the implication of a bilingual speaker. This paper aims at analyzing the types and factors of using code switching by male participants and female participants in Indonesian TV talk shows. Data in this study is taken from a corpus of transcribed spoken text (82.270 words in total) from total 17 episodes from two talk shows aired on two different television programs. The results show that female and male participants in their roles as hosts, guests, and co-host switch codes in their speech. They can be said to be creative and innovative speakers

Language is related to the way people communicate with one another in every day interaction. In studying a language, we are much concerned with people or society in which the language is used. The study of language and society is known as sociolinguistics. Holmes (2001) defines Sociolinguistics as the study of the relationship between a language and society. The way people use a language related to social factors, such as participants including social distant and status, the setting (formality scale), the topic and the function of using the language. Some additional aspects of these factors are differences in regional and social dialect, gender differences, and bilingualism.

According to Wardough (2006:101), in multilingual society, there are few single-code speakers as an impact of language contact. The bilingual speakers are usually required to select a particular code- dialect, style or register whenever they choose to speak, and also decide to switch from one code to another or mixing codes even within sometimes very short utterances. A code is a system used for communication between two or more parties. In addition, Wardough said that creating a new code in a process of using a language known as CS. Code Switching (hereafter CS) is an important aspect of bilingualism. CS (also called code-mixing) can occur in conversation between speakers’ turns or within a single speaker’s turn. In the latter case it can occur between sentences (inter-sentential) or within a single sentence (intra-sentential). Broadly defined, CS is the ability on the part of bilinguals to alternate effortlessly between their two

languages. Hornberger& McKay (2010) defined CS as a phenomenon when there are two or more languages exist in a community and it makes speakers frequently switch from one language to another language (Wardough, 2006:101; Bullock &Toribio, 2009:2).

Poplack (1980) classified code-switching into: (1) tag-switching; (2) Inter-sentential switching; and (3) Intra-sentential switching. Tag-switching involves the insertion of a tag in one language into an utterance which is otherwise entirely in other language. Inter-sentential switching involves a switch at a clause or sentence boundary, where each clause or sentence is in one language or another. Intra-sentential code switching occurs when the alternation of language used is below sentential boundaries.

Meanwhile, Myer-Scotton (1989) proposed intra-word code switching, which occur within word boundary. She proposed Matrix Language Frame (hereafter MLF). In intra-word CS there is a dominant language at work. Thus, one language is assigned in the status of ‘matrix language’ (hereafter ML). The ML supplies the grammatical frame of the constituent, while morpheme is supplied by both languages. The content morpheme is from another language, and the embedded language (EL) may appear in this grammatical frame as well as matrix language (ML) and content morpheme. The example given is si ku-come, si pronoun, first person singular. ku tense marker denoting the past and denoting negation. Come verb, English. It should be noted that the system morpheme (tense marker, negation marker) are all in Swahili, while content morpheme (verb) is in English. Therefore, the ML is Swahili while English is the EL. According to Myer-Scotton (1989), there is always ML in bilingual communities.

Code differences based on gender are mostly related to opportunities for mobility into dominant culture, social role of the speaker and the structure of labor market. They are not influenced by their status being a man or a woman. Their language behavior in using different code and even adopted variation of dominant group is a kind of innovative tendencies (Smith, 1979: 120—122, Chamber, 2003: 138, Coates, 2004: 6).

According to folk linguistics, gender differences in language are mostly related to their social status being men or women. Such claim raised many protests. Gillieron, a famous dialectologist, stated that women easily receive and use new words than men do. The use of new word is an indicator of innovative and creative speaker in using a language (Pop, 1950:195; Coates, 1986: 42; Coates, 2004: 11, 35).

Holmes (2001) stated that women or men are sometimes the innovator and leading to language change. Women in Charmay, small village in Switzerland used new variants. In Norwich, women are leading changes towards RP in different vowel, while men in Belfast are introducing new vernacular variants. Clonard women are introducing into their community a speech feature of the more prestigious Ballymacarrett community. The generalization about women leading change towards the standard dialect applies only where women play some role in public social life (Holmes, 2001: 209—212).

The women and men from two immigrant communities in the UK, the Greek Cypriots and the Punyabi reported by Gardner-Chloros (1992) that there were no significant differences in using CS by them. Thus, the result does not support the hypothesis that women substantially use CS less than men.

The previous study relevant to this paper is conducted by Yuliana, Rosa and Sarwendah (2015). They investigated the types of code switching and code mixing employed by Indonesian celebrities. Their study consists of two groups. The celebrities of native speaker’s parents are classified in group I, and those who are capable of speaking two or more languages are put in group II. The result shows that the celebrities in group II use more code-mixing and code-

switching with a different frequency and speak foreign language more actively. My study is different in that their analysis is not related to gender differences.

The various choices of code will have different social meaning. Gal (1988, p. 247) says, ‘CS is a conversational strategy used to establish, cross or destroy group boundaries; to create, evoke or change interpersonal relations with their rights and obligation’. There are some reason of doing CS proposed by Grosjean, such as: fulfill linguistic need for lexical item, set phrase, discourse marker, or sentence filler; continue the last language; quote someone; specify addressee; qualify message (emphasize); specify speaker involvement (personalize message); mark and emphasize group identity (solidarity); convey confidentiality, anger, or annoyance; exclude someone from conversation, change role of speaker (raise status, add authority, and show expertise (Grosjean, 1982: 152)

The present study focused on the type and factor of using CS by male and female participants in Indonesian TV talk shows. The types of CS are said to be linguistic variables that are employed differently by different gender. The result will be qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed based on gender perspective.

The data in this study is taken from a corpus of transcribed text (82.270 words in total), comprising of total 17 episodes from two talk shows aired on two different television programs. The corpus data is thus a transcribed spoken text produced by participants in both talk shows. All episodes are broadcasted between 2011 –2013.

The first talk show is Just Alvin (henceforth T JA), which has a male host (abbreviated as MH). The second talk show is So Imah Show (henceforth T SIS), which has a female host (abbreviated as FH). All the invited guests in these talk shows are celebrities; they rarely meet each other guest. The total guests invited in both talk shows are 73 persons which consists of 34 female guests (abbreviated to FG) and 39 male guests (abbreviated to MG). The participants in both talk shows are those from public personae and all of them play social role as artists. All of them use Indonesian as their language background. In the conversation they switch their language into English, since English as their second language.

The data are analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively to compare the use of CS by male participants (MP) and female participants (FP) in both talk shows. MP involves male host (abbreviated to MH), MG and male co-host (abbreviated to M Co-H). FP involves female host (abbreviated to FH), FG and female co-host (abbreviated to F Co-H).

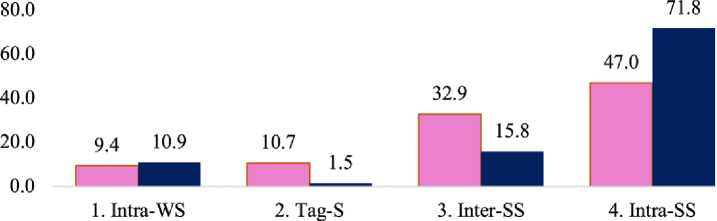

Based on the analysis, the results show that all types of CS are employed by MP and FP in both T JA and T SIS. The types are tag-switching, inter-sentential switching, intra-sentential switching, and intra-word switching as displayed in figure 1.

The Percentage of Code Switching by MP and FP

■ FP (Female Participant) ■ MP (Male Participant)

Figure 1. The percentage of Code-Switching type by MP and FP

Figure 1 shows that intra-SS is mostly employed by MP and FP. They are different in that both MP and FP employed intra-SS in different percentage. MP employ intra-SS in 71.8% while FP in 47%. In the following discussion, each of CS types employed in T JA and T SIS will be presented. The first type discussed is Intra-WS since it is rarely put in the researcher’s consideration.

Intra-WS found in my study support Myer-Scotton’s finding that there is always Intra-WS in bilingual community. The occurrence of intra-WS is 79 times. FP employed intra-WS (10,7%) higher than MP does, who employed it in 1,5% as shown in Figure 1.

Myer-Scotton (1989) proposed intra-word code switching, which occur within word boundary. She proposes Matrix Language Frame (MLF) that consists of Matrix language (ML) and Embedded Language (EL) in analyzing intra-word switching (hereafter Intra-WS).

In my study, the ML in MLF is in Indonesian, such as CJI suffix –in and prefix me- , meN-, and N-. They are verbs forming affixes that are attached to (i) verb phrase (back-up-in ‘to give back-up’) (see example (1)), (ii) verb (me-launching ‘to launch’, me-release ‘to release’, meng-operate ‘to operate’, (iii) noun (nge-fans ‘to be a fans (of someone)’, nge-gym ‘to go to gym’, nge-date ‘to have romantic date’, and nge-match ‘to adjust’. In these examples, the English words back up, launching, operate, release, gym, date, fan, and match are the Embedded Language (EL). Passive prefix di- as the ML can also attach to English EL, such as di-cancel ‘to be cancelled’ and di-share ‘to be shared’. The di- passive prefix attached to EL corresponds to CJI passive prefix ke- (see (2)).

-

(1) MH: … kalo nggak ada ya siapa back up-in if not exist yes who back-up-CAUS ‘if there is none who would do the back up?

ya? (JA M 2, 151) yes

-

(2) F: ... jadi mungkin aku kayak ke-built seperti itu, ... (JA F 6, 275)

… so probably I be.like PASS-build that way …

‘so probably, I was like being built/nurtured that way’

Indonesian prefix –nya as ML is generally attached to verb in (3), to VP in (4) to adjective in (5), and to noun in (6) as EL category in the frame and function as nominalizer.

-

(3) FG: Tapi by the way suka yah set-nya ungu. (JA F 8, 348) But by the way like yes set-nml purple ‘But by the way, I really like the setting in purple.’

-

(4) MH: Ok. Terus hari ini bisa di-bilang comeback-nya Reza (JA F5, 176)

Ok. Then day this can pass-sat comeback-nml name

‘Ok. Then, today, it can be said as the comeback of Reza.’

mature most important. that mature-nml

‘being mature is the most important. That is the mature.’

-

(6) MH: pribadi (…) seperti Robert Pattinson itu ya. Look-nya, style-nya... (JA F 6, 364) persona like name that yes. look-nml, style-nml

‘the persona like Robert Pattinson. The appearance, the style…’

MLF, such as prefix se-, ter-, particle –lah shown in examples (7) to (10) below, function as emphasizer. The EL of the example given are adjective (simple) (7), verb (update, declare) ((8) and (9)), and phrasal verb (make sense) (10).

-

(7) MH: mungkin keliatannya simple ya? tapi nggak se-simple itu mungkin ya? (JA M 2, 323) maybe appear simple yes but not as-simple that maybe yes

‘it appears simple, right? But it is probably not as simple as that, right?’

news most-update from quant name and family

‘the most updated news from Ahmad Dhani dan (his) family…’

laughter. declare-emph declare

‘hahahaha. Let’s declare, you know declare’

-

(10) FG: Jadi kalo sekarang aku langsing normal, maksudnya make sense-lah gitu kan

so if now I karena jarak

because distance

slim normal, the.meaning make sense-emp, like.that tag melahirkannya juga sudah jauh… (SI F 10, 328) give.birth also already far

‘So, if I am now slim, I mean it makes sense, isn’t it, because it has been a while since I

delivered (a baby)…’

In example (11) to (13) below, the ML suffix –nya corresponds to definiteness marker ‘the’. It can attach to the ELs noun phrases namely sound system (11), image (12), and host (13):

it.seems crazy like.that sound system-def

the sound system seems so crazy/awesome…

so it.seems image-def only that-red just yes

‘so the image does never change… right?’

Ok so rel name ov.do become host-def

‘ok, so what you, Agnes, did was to be the host?

The suffix -nya functions as ligature or linker before possessive noun as in (14) and linker before pronoun, usually first person as in (15).

‘How is Maia’s performance? Dev?’

because ‘hero’ image-LIG I tag?

‘because ‘hero’ is my image, isn’t it?’

The usage of Intra-WS is influenced by the factor to fulfill the linguistic items that are framed in ML and EL. The ML function as nominalizer, verbalizer, definiteness marker, and linker/ligature to emphasize the message.

Data in Figure 1 shows that most of the tags are employed by FP (10.7%), while MP only used 1.5%. Tag switching (hereafter Tag-S) involves the insertion of one language into an utterance which is otherwise entirely in the other language, such as you know, I mean,I wish you know, no way, …didn’t they, etc. Tags are subject to minimal syntactic restriction; they may be easily inserted at a number of points in a monolingual utterance. Tag-S is used to mark injection or to serve as sentence fillers (Romaine, 1995: 121--122, 162). The universal tags are yeeah, right, well (online Cambridge Dictionary).

In this study, Tag-S found in the forms of words involves well, right, actually, okay, so, then, and take the forms of phrasal items (the terms proposed by O’Keeffe (2006)) such as you understand, no problem, by the way, all right, I mean, it's ok, but it doesn’t mean, why not, I Know, right, I don't mind, oh my god, my god, that's why, actually, to be honest, as long, you know, oh my goodness, so basically, like that and so far. They help to fulfill the linguistic need for discourse markers or sentence filler.

Well in (16) below is used to introduce new topic. In (17), discourse marker right is used as rhetorical statement to invite the listener’s agreement and response to the speaker’s utterance.

and they interview me about name like.that

Well, Aaa dan aku punya banyak cerita sih waktu jaman-jaman waktu dulu Well name and I have many story when period-red time past

‘… and they interviewed me about Nike. Well, Aaa and I have many old stories in the past’

but yes also I’m not the one who got divorce yes [HM: eemm] right

‘but yeah, also, I’m not the one who got divorce, right’

Tags such as you understand (18), I was thinking, I mean (19), and you know (20) are classified as sentence filler. They serve as discourse marker used to emphasize the statement in which it is inserted.

one this woman rel poss.chatty excl also you understand

‘…this one woman who is also, oh my God, very chatty. You understand?’

we want hear name for bring all song name.poss

and then, I was thinking, I mean, yaah, nggak masalah juga sih. and then I was thinking I mean, OK not problem also part ‘…we want to listen to Nava singing all Nike’s songs… and then, I was thinking, I mean, it is not a problem indeed.’

but at end.def I for.instance I see character.def

nggak nggak you know nggak he's not the right person ya aku pikir (JAF6, 382) not not you know not he’s not the right person yes I think

‘…but at the end I noticed the characters, you know, I think it is a “no” from me, he is not the right person I think’

My god and my goodness are categorized as exclamation. These tags are used to express the speaker’s feeling of being surprised (see (21) and (22)).

see name loc TV surely my God want have man like name

‘… (I have been) seeing Gerry on TV and I’m clearly like My God… I want to have a boyfriend like Gerry’

-

(22) FG: bukan seseorang yang oh my God benar-benar yang bisa menghargai Nuri not someone rel oh my God truly rel can appreciate name

‘… not somebody that oh my God can truly appreciate Nuri’ (JA F7,305)

Actually, so, to be honest, as long, then actually, so far, like that, but it does not mean, and why not are discourse markers to emphasize and qualify the message being uttered. Some of the usages are given in examples (23) until (25):

-

(23) FG: Actually bukan aku yang menyampaikan gitu, ... (JA F7, 39) actually not I rel say like.that

‘Actually it was not me who said like that’

-

(24) FG: To be honest, mmm... begitu pulang ke Jakarta setelah pulang Umroh,

to be hones soon go.home to Jakarta after go.home umroh

sakitnya tuh udah nggak ada ya,... (JA F7, 38)

sick.nml that already not exist yes

‘To be honest, mmm… soon after arriving in Jakarta after Umrah, I did not feel pain anymore…’

-

(25) FG : as long...ya sampe aku ketemu ama the right one. aku nggak mau... (JA F 6, 392) as long well until I meet with the right one I not want

‘as long as…well until I meet the right one. I do not want…’

3.3 Inter-sentential switching

Inter-SS occur at a clause or sentence boundaries, where each clause or sentence is in one language or another in single speaker’s turn. Sometimes, it occurs between speaker turn. In inter-SS greater fluency is required in both languages (Romaine, 1995: 122). In this study, FP uses Inter-SS (32.9%) among the other types, whereas MP employed 15.8% among CS types they applied (cf. Figure 1). Example (26) shows Inter-SS between the parties. While example (27) shows Inter-SS in single speaker’s utterance.

approximately what part tips rel make you.pl become (male) widower cool

‘What would be the tips to make you guys be cool (male) divorcee/widower…’

MG: Enjoy the life aja. (SI M 15, 581)

Enjoy the life just

‘Just enjoy the life’

time.def not too long yes it.appears yes

‘The time is not too long, apparently, right?

FG : tidak pacaran, jadi baru kenal langsung dilamar …. This is a true story

Not dating so just know directly pass.propose this is a true story

‘we were not dating; so once we met, he proposed me directly. This is a true story.’

3.4 Intra-sentential switching

Intra-sentential switching (hereafter intra-SS), involves the greatest syntactic risk. It is generally employed by the most fluent bilinguals. It occurs within a clause or sentence boundary. It is considered that intra-SS include mixing between word boundaries (e.g. English word with Punjabi inflectional morphology (Romaine, 1995: 123). In this study, Intra-SS is the most frequent type among other types of CS (see Figure 1). MP employed it in 71.8% of the cases, while FP used it for 46.9%.

English words repackage in (28), then cleansing, smoothing, balancing, and spooring in (29), as well as the phrase hot mama in (30), are employed to fulfill the linguistic item that can qualify the message.

bringing all song name.poss for repackage again ‘…singing all Nike’s songs for repackaging again…’

treatment.def change-red I diligent rel name.def

kayak cleansing, smoothing, balancing, spooring. (SIM 15, 591) like cleansing smoothing balancing spooring

‘the treatments keep changing, I often do cleansing, smoothing, balancing, spooring’

it.means this already counting not hot mama again

‘it means this is not counted as hot mama anymore.’

Welcome back given in (31) express solidarity while everything, whatever, what happen in (32) express confidentiality, that is not to convey the message explicitly.

-

(31) MH : Welcome back Haha,,haha,, Apa kabar bro… (JA M 1. 4) welcome back laughter how.are.you brother ‘wecome back haha,,haha,, how are you, bro…’

what part meaning family make name ‘what is the meaning of “family” for you, Agnes?’

FG : everything, karena memang aku dibesarkan di keluarga yang sangat menjunjung tinggi everything since indeed I pass.raise in family rel very hold high

masalah itu, gitu. Jadi, kayak itu, kayak keluarga mafia aja gitu ha,ha

problem that like.that so like that like family mafia just like.that laughter

whatever, what happens in the families stays in the family.. (JA M 6, 98)

whatever, what happens in the families stays in the family

‘everything, I indeed was raised in a family that praise those matters. So, it seems like a mafia family hahahaha, whatever, what happens in the families stays in the family...’

The most dominant factor in employing all types of CS is to fulfill the linguistic need for words, phrases, sentence, clause, discourse marker, sentence filler. The employment of Intra-WS in the form of MLs (e.g., Indonesian prefixes, suffixes, CJI in- and ke-, and discourse particle – nya) that are attached to the ELs (i.e. English words and phrasal verbs) are influenced by the factor to fulfill the linguistic items in both Indonesian and English as forming noun, verb/VP, definiteness, and linker/ligature to emphasize the message.

The reason of using tag-S is to fulfill the linguistic items for discourse marker and sentence filler. Tags in the forms of exclamation, words, chunk of words in tag-S serve as discourse marker to emphasize and qualify the statement being uttered by the speaker as well as to express speaker’s feeling and emotion.

The linguistic items found as inter-SS are mostly influenced by the reason to fulfill linguistic need that could not only express what the speakers want to convey, but also raise the speaker status as bilingual person.

In Intra-SS, the words and phrases inserted in speaker’s utterance vary in the form to qualify the intentional message being uttered. They can also help to express confidentiality—not to convey the message explicitly as given in example (32).

In addition, CS serve expressive function, that is to convey the speaker’s feeling and emotion through tag switching and intra-word switching, express the speaker’s expertise being able to convey their feeling by inserting English words, phrases, sentence, or clause in their utterance. CS also express social relation between the parties, supposed that they have close relation.

Since media interaction is classified as formal context that the use of CS in both TV talk shows -T JA and T SIS considered as conversational strategy to establish intimacy, especially pseudo-intimacy. It means that both MP and FP use CS to express social meaning (Gal, 1988: 247; O’Keffee, 2006:5).

-

Figure 1 illustrates the use of CS by MP and FP as host and guest and CoHost. As Figure 1 shows, there are slight differences in the usage of intra-WS by both gender. However, FP shows greater preference of using inter-SS (32.8%) and TS (10.7%) compared to MP. On the contrary, MP show greater preference of using intra-SS (71.8%) and Intra-WS (10.9) compared to FP. Thus, the evidence from this study suggests that both MP and FP in T JA and T SIS employed the same type of CS but in fifferent frequency.

-

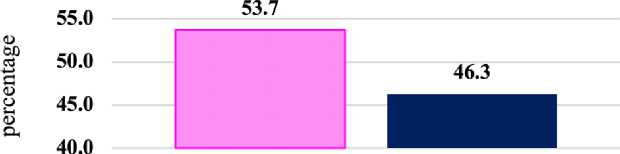

Figure 2 presents the cummulative percentage of CS. In this figure, the types of CS is collapsed into the use of CS from different gender—MP ‘Male Participants’ (MG+MH+Mco-H) and FP ‘Female Participants’(FG+FH+Fco-H).

The usage of Code Switching by MP and FP

gender of participants

-

□ FP (Female Participan) ■ MP (Male Participants)

-

Figure 2. Percentage of using CS by MP and FP in T JA and T SIS

As presented in Figure 2, it could be stated that both MP and FP employed all types of CS. FP shows greater preference of using CS (53.7%), compared to MP (46.3%). By using CS in the various forms of English linguistic items (English words, phrases, sentences, and clause in their utterances), both MP and FP in T JA and T SIS are creative and innovative speakers in using a language. The use of CS is considered as linguistic strategy that raise the speaker’s (i.e. MP and FP’s) status of being able to switch their code into English in their utterances (Expressive function). The most interesting result in my study is their innovativeness in employing intra-WS. They are quite creative in using Indonesian prefix, suffix, and particles as MLF and choose English words and phrases as EL. For this reason, the result of my study support Gillieron and Pop (1950) on the one hand, because FP is not only as creative speakers, but they are also

innovative speakers. On the contrary, my study is contradictory to Gillieron’s claim in that MP employs CS in their utterances even though in lower percentage than the FP does (cf. Figure 2).

This study takes, and contributes to, the growing trend in usage-based, functional linguistics in adopting corpus-based, quantitative method to study language use and variation in sociolinguistics (cf., e.g., Delbecque et al., 2005). In particular, this study demonstrates how relative frequency data (i.e. percentages) reveals the relative prominence of the types of codeswitching in actual, non-elicited language use (i.e. in the context of media interaction, namely TV show) (cf. de Klerk, 2006). Moreover, the inclusion of sociolinguistic variable such as gender enriches the characterization for (i) how these code-switching types vary with respect to gender, and (ii) what these usage variations reveal regarding discoursal, conversational strategy of the talk show participants (e.g., to establish [pseudo-]intimacy, to demonstrate creativity of the speakers, to fill language gap in the expression of certain intentions).

Based on the result, all types of CS (Tag-S, Inter-SS, and Intra-SS) proposed by Poplack (1980) and Intra-WS proposed by Myer-Scotton (1989) are found in T JA and T SIS that are broadcasted in Indonesian TV talk show. The linguistic items employed as CS is mostly influenced by the reason to fulfill linguistic need that could not only express what the speakers want to convey, but also raise the speaker status as bilingual person. Since media interaction is classified as formal context that the use of CS in both TV talk shows -T JA and T SIS to be considered as conversational strategy to establish intimacy, especially pseudo-intimacy. It means that both MP and FP use CS to express social meaning (Gal, 1988: 247; O’Keffee, 2006:5). In addition, by using CS in the various forms of English linguistic items, both MP and FP in T JA and T SIS are creative and innovative speakers in using a language.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank all those who have given valuable contributions to this research so that the results can be disseminated through publication, especially to the eexaminers: Prof. Drs. I Made Suastra, Ph.D, Prof. Dr. N.L. Sutjiati Beratha, M.A., Prof. Dr. I Wayan Pastika, M.S., Prof. Dr. Aron Meko Mbete., Prof. Dr. I Ketut Darma Laksana, M.Hum., Prof. Dr. Made Budiarsa, M.A., Prof. Dr. I Dw. Komang Tantra, M.Sc., Dr. Ni Made Dhanawaty, M.S., for their advices to deepen the analysis and presentation of appropriate research results.

References:

Bloomfield, Leonard (1933). Language. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Chambers, J. 2003. Sociolinguistic Theory. 2nd edition. Oxford:Blackwell.

Coates, J. 1986. Women, Man, and Languages. Hong Kong: Longman.

Coates, J. 1998. Language and Gender: A Reader . Blackwell.

Coates. 2004. Women, Man, and Languages (third edition), Hong Kong: Longman.

Coulmas, 1998. The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Blackwell Reference online.

Creswell, J W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Delbecque, N., van der Auwera, J., & Geeraerts, D. (Eds.). (2005). Perspectives on variation: Sociolinguistic, historical, comparative. Mouton de Gruyter.

de Klerk, V. (2006). Codeswitching, Borrowing and Mixing in a Corpus of Xhosa English.

International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(5), 597–614.

https://doi.org/10.2167/beb382.0

Eckert, P, Ginet. 2003. Langauge and Jender. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Gal, Susan (1988). The political economy of code choice. In M. Heller (ed.),Codeswitching: Anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives, pp. 245–264.

Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Gardner-Chloros, Penelope (1992). The sociolinguistics of the Greek-Cypriot community in

London. In M. Karyolemou (ed.), Plurilinguismes:

Grosjean, F. 1982. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gumperz, J. J. (1973, April). The communicative competence of bilinguals: Some hypotheses and suggestions for research. Language in Society,2(1), 143–154.

Holmes, J. 2001. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. New York: Longman Publishing.

Hornberger, N. H., & McKay, S. L. (2010). Sociolinguistics and Language Education. Great Britain: Short Run Press.

Labov, W. “The intersection of sex and social class inthe course of linguistic change.”Language Variation and Change 2 (1990) 205-254)

O’Keeffe, A. 2006. Investigating Media Discourse. In McCarthy M (ed), Domain of Discourse. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group

Sociolinguistique du Grec et de la Gre`ce, 4, pp. 112–136. Paris: Centre d’e´tudes et de recherches en planification linguistique (CERPL).

Poplack, S. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start the sentence in English y terminό en español: toward a typology of code-switching, Linguistics 18: 581 – 618.

Qismullah, Y,Y, Fata, I, A, Chyntya. 2018. Types of Indonesian English code switching employed in a novel. Kasertsart Journal of Social Sciences. 1—6

Romaine, S. 1995. Bilingualism. Oxford, UK: Blackwell

Scotton and Jake. 2009. A universal modelof code-switchingand bilingual languageprocessing and production. In Bullock, B, E, Toribio, A, J (eds), The CambridgeHandbook of LinguisticCode-switching. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, P.M. 1979. Sex Marker in Speech. In Scherer, K. R. and Giles, H. (eds). Social Markers in Speech.p 109—134). 1st edition. Great Britain: Cambridge University

Press.

Stockwell, P. (2002). Sociolinguistics: A Resource book for students. London: Routledge. Norwich.Language in Society , (1) , 179 95. #1#, #8#.

Trudgill, P. (1974). Sociolinguistics: An introduction to language and society (Fourth). England: Penguin Books.

Wardhaugh, R. 2006. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Yuliana, N; Luziana, A,R, Sarwendah, P. 2015.Code Mixing and Code Switching of Indonesian Celebrities. A Comparative Study. In Jurnal LINGUA CULTURA Vol.9 No.1 May 2015

Biography of Author

Dra. Luh Putu Laksminy, M.Hum

A Doctoral candidate in Linguistics, and lecturer at the English Department, Faculty of Arts, Udayana University, Indonesia.

Discussion and feedback