10.24843 Construction of The Verb Sequence Menjuruh in The Classic Malay Language

on

e-Journal of Linguistics

DOAJ Indexed (Since 15 Sep 2015)

e-ISSN: 2442-7586 p-ISSN: 2541-551

July 2018 Vol. 12 No. 2 P:100—118

DOI. 10.24843/eJL.2018.v12.i02.p.03

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eol/

Construction of The Verb Sequence Menjuruh in The Classic Malay Language

1I Made Madia, FIB Udayana University

-

2Ketut Artawa, ketut_artawa@unud.ac.id, Udayana University

3

I Wayan Pastika, wayanpastika@unud.ac.id, Udayana University

-

4I Ketut Darma Laksana, darmalaksana27@yahoo.com, Udayana University

*Corresponding Author: de.mad58@yahoo.co.id

Received Date: 13-12-2017 Accepted Date: 02-03-2018 Published Date: 11 July 2018

Abstract— The construction of verbs sequence ‘konstruksi verba beruntun’, which is hereinafter abbreviated to KVB, in this article is defined as a construction without the existence of any linking word and pausing mark (comma). Based on the theory of typology, as far as the complex predicate is concerned, the only KVB menjuruh+Vitr (intransitive verb) whose grammatical object functioning as the nucleus argument located after V2 (the second verb) and KVB menjuruh+Vtr (transitive verb) which is not marked by the morphological prefix meng- are identified as having the complex predicate construction ‘kontruksi predikat kompleks’ which is hereinafter abbreviated to KPK. Based on the theory of transformational grammar, the KVB menjuruh, except that identified as KPK, is identified as having the complex clausal construction ‘konstruksi klausa kompleks’, which is hereinafter abbreviated to KKK.

Keywords: construction of verbs sequence, construction of complex predicate, construction of complex clause

The classic Malay language ‘bahasa Melayu klasik’ which is hereinafter abbreviated to BMK was used between the 15th century and the 18th century (Collins, 2005). The Malay language used in literature, culture, religion, and in the matters pertaining to the form of government shows that the impact of the Arabic culture, which was introduced through Islam, was highly strong. The text of the history of Malay ‘Sedjarah Melaju’, which was written in 1612 and is hereinafter abbreviated to SM (Situmorang, 1952, 1958) is representative enough to show the use of BMK. The other text which can also represent the use of BMK is the book Hikajat Abdullah, which is hereinafter abbreviated to HA (Datoek Besar, 1953). It narrates the biography of Abdullah (ibn Abdulkadir Munsji) starting from 1976 to 1853.

The KVB in this article is defined as the existence of (at least) two verbs in a construction without the existence of any linking word and pausing mark (comma). Syntactically, the KVB menjuruh can be in the construction V1+V2 without any linguistic

100

constituent between V1 (the first verb) and V2 (the second verb). It can also be in the construction V1+X+V2 with the existence of a linguistic constituent, excluding linking word and pausing mark (commat), between V1 and V2. The article written by Dol (1996) and Menick (1996), in which the terms sequences of verbs and verbs sequence are used, has inspired the term KVB. In this article, the concept KVB is different from the concept KVB used by several writers before. According to Pradnyayanti (2010), the term KVB is equivalent to the term KVS ‘konstruksi verba serial’ (the construction of serial verb). Mas Indrawati, in her dissertation, states that the term KVB is identical with the term KPK. Furthermore, Subiyanto (2010) claims that KVB can be in the form of both KVS and KPK.

The verb menjuruh in BMK is an action verb which requires a complement (clause). Semantically, it means ‘memberikan perintah kepada seseorang untuk melakukan sesuatu tindakan’ (asking someone to do something). The verb menjuruh or menjuruhkan was used productively enough in BMK. Among 74,183 words used in SM, the verb menjuruh or menjuruhkan was used 133 times, meaning that 0.19% of the words used in SM was dominated by the verb menjuruh or menjuruhkan. If compared to the use of the verb memerintah or memerintahkan, which, semantically, has the same meaning as the verb menjuruh or menjuruhkan, there is a significant difference. In SM the verb memerintah or memerintahkan is only used 7 times (0.009%).

The productive use of the verb menjuruh has been the main reason why it is used as the topic of this article. The discussion in the current study covers three things; they are (i) the description of the verb menjuruh; (ii) the analysis of the KVB menjuruh as KPK, and (iii) the analysis of the KVB menjuruh as KKK.

This current study is an inductive-descriptive-explanative one. Collecting data using observational method and note taking technique initiated the study. The descriptive study attempts to identify and classify data based on the linguistic intuition parameter (see Keraf, 1981: 94). The explanative study attempts to present an analysis of or explanation on the evaluation of linguistic data, meaning that the explanative study attempts to explain why the speaker and addressee tend to choose and use particular sentence constructions (see Karim,

101

1988:226). In this current study a written text taken from the book SM was used as the data source (Situmorang, 1952, 1958) and HA (Datoek Besar, 1953). Therefore, the data are still in the original form, meaning that the data are still written using the Old Spelling (the Soewandi spelling/Republic spelling).

Based on the characteristics of the collected data, the KVB menjuruh in the text BMK requires two theories in order to be able to explain it comprehensively. They are the theory of complex predicate typology and the theory of transformational grammar.

A complex predicate, as far as its wide definition is concerned, is defined as a predicate which is made up of more than one (sub)predicate. The relation among the (sub)predicates varies; many are in the form of complementation structure and many others are in the form of serial structure (Arka et al., 2007: 187). In this article, the complex predicate in the form of complementation structure is emphasized. KPK can be determined phonologically, syntactically, and semantically (see Durie, 1997l van Staden, 2008; Kroeger, 2004; Aikhenvald, 2004; Senft, 2008; and Artawa, 2010). Phonologically, KPK is uttered in one unit of intonation, meaning that there is no pause between the verbs forming KPK. Syntactically, KPK has the following characteristics: (i) one of the verbs, namely V1 in KPK is the nucleus one, and the other, namely V2 is the subordinate one; (ii) it is monoclausal in nature (consisting of one clause); (iii) the verbs forming KPK share the same aspect, modality, and negation markers; and (iv) the verbs forming KPK share at least one argument. Semantically, KPK expresses one event or sub-events of one single event.

From 1957 to 1980s the theory of transformation grammar developed fast enough. Based on the phases during which it developed, it can be classified into four; they are (1) the phase during which the Syntactic Structure developed (1957—1964), (2) the phase during which the Standard Theory developed (1964—1972), (3) the phase during which the Standard Theory developed, resulting in the Extended Standard Theory (abbreviated to EST) and during which the Extended Standard Theory was revised, resulting in the Revised Extended Standard Theory (the Revised EST); this took place in 1970s, and (4) the phase during which the Theory of Government and Binding ‘Teori Penguasaan dan Ikatan (abbreviated to TPI)

102

was developed; this took place in 1980s (cf. Dardjowidjojo, 1987: 5 and Silitonga, 1990: 18—47). The model of analysis used in this current study is the phrase structure syntax, as one of standard versions developed after 1965. This model is highly similar to the analysis of immediate constituent analysis (see Sariyan, 1988 and Lapoliwa, 1990). The theory of transformational grammar consists of three components; they are syntax, phonology, and semantics. Syntax includes phrase structure, lexicon, and rule. Phonology includes deletion, filter, and phonological rules. Semantics includes the linguistically interpretative rules (grammar) and the cognitively interpretative rule. The linguistically interpretative rules change the deep structure of sentences into the logical forms. The logical forms and the cognitively interpretative rules produce semantic representations of sentences (Silitonga, 1990: 36 and Lapoliwa, 1990: 14).

There are several reasons why the theory of transformational grammar was chosen. First, it is reliable enough to use the transformational grammar using the sentence as the biggest unit to analyze the KVB menjuruh as KKK. Second, the transformational grammar is concerned with where a sentence construction comes from. What the transformation grammar is concerned with is which structure is the kernel and which is derived. In a derived construction it is concerned with where the structure comes from and how it is transformed. Third, the concepts of deep structure and surface structure which characterize the transformational grammar allow a researcher to explain the phenomenon that the components of a clause are not complete from the surface structure point of view; however, it can be felt that it is a clause.

Syntactically, the verb menjuruh is a transitive verb which requires the existence of two nucleus arguments, one functions as the grammatical subject and the other functions as the grammatical object. Based on the linguistic element existing between the verb menjuruh and V2, the KVB menjuruh can be grouped into two types; they are (i) the KVB menjuruh+V2 and (ii) the KVB menjuruh+X+V2 in which X is the linguistic element; however, the linking word and/or pausing mark (comma) are not included.

103

-

4.1.2 Description of the KVB Menjuruh+V2

Based on the grammatical type of V2, the KVB menjuruh+V2 can be grouped into two: they are the KVB menjuruh+Vitr and the KVB menjuruh+Vtr.

-

(a) KVB menjuruh+Vitr

-

(1) maka baginda me-njuruh ber-tanja (SM, 7.4:21)

CONJ baginda ACT-suruh (Vtr) ACT-tanya (Vitr)

’(maka) baginda menyuruh (orang) bertanya’ ‘(so) His Excellency asks someone to ask’

Baginda functions as the grammatical subject and nucleus argument (1); however, the grammatical object, as the other nucleus argument, that is, orang does not appear, as it is generic-indefinite in nature. This grammatical object, as the other nucleus argument, functions as the grammatical subject of V2 bertanja. As an intransitive verb, it does not need any grammatical object, the other nucleus argument, to appear. The fact that the appearance of the noun phrase (NP) orang has more than one function as can be seen in data (1) can be proved by the appearance of the NP orang in data (2).

-

(2) patih aria gadjah mada me-njuruh orang

patih arya NAME ACT-suruh (Vtr) orang

ber-djaga2 (SM, 14.16:133)

ACT-jaga-jaga

‘patih arya gajah mada menyuruh orang berjaga-jaga’ ‘Chief Minister Gajah Mada asks someone to stay awake’

Data (3) is another example of the KVB menjuruh+Vitr as in data (1); however, the nucleus argument, namely the grammatical object of V1 menjuruh, is specific-definite in nature, supai itu.

-

(3) orang me-njuruh lari supai itu (HA)

orang ACT-suruh (Vtr) lari (Vitr) serdadu PRON

‘orang menyuruh lari serdadu (india) itu’ ‘someone asks the indian soldiers to run’

-

(b) The KVB menjuruh+Vtr

-

(4) machdum-pun me-njuruh me-manggil tun

NAME-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) ACT-panggil (Vtr) tuan

bidja wangsa (SM, 20.5:68)

NAME

104

‘machdum pun menyuruh (orang) memanggil tuan bija wangsa’ ‘Machdum also asks (someone) to call Mr. BijaWangsa’

The nucleus argument, that is, the grammatical subject of V1 menjuruh (4) is machdum; however, the grammatical object, that is, orang, as the other nucleus argument, does not appear as it is generic-indefinite in nature. At the same time this grammatical object also functions as the grammatical subject of V2 memanggil. As a transitive verb, the V2 memanggil requires the existence of the grammatical object, that is, tun bija wangsa, as the other nucleus argument. Data (5) is another example of the KVB menjuruh+Vtr as in data (4).

-

(5) maka baginda me-njuruh me-njerang pahang (SM, 17.4:33)

CONJ baginda ACT-suruh (Vtr) ACT-serang (Vtr) NAME

‘(maka) baginda menyuruh (orang) menyerang pahang’

‘(so) His Excellency asks (someone) to attack Pahang’

Data (6) is another example of the KVB menjuruh+Vtras data (4)-(5); however, the second Vtris in the form of a verb without the prefix morphological marker meng-.

-

(6) maka baginda me-njuruh tutup pintu kota (SM, 1.13:91)

KONJ baginda AKT-suruh(Vtr) tutup (Vtr) pintu kota

’(maka) baginda menyuruh (orang) menutup pintu kota’ ‘(so) His xcellency asks (someone) to close the town door’

Based on the direction from which the linguistic constituent refers to the verb, the KVB menjuruh+X+V2 can be further described as the KVB menjuruh÷X÷V2, the KVB menjuruh ÷X+V2, the KVB menjuruh+X÷V2 and the KVB menjuruh÷X1+X2÷V2.

-

(a) The KVB menjuruh ,÷X÷V2

-

(7) ia me-njuruh orang me-mukul tjanang (SM, 14.4:27)

3T AKT-suruh (Vtr) orang AKT-pukul (Vtr) canang

‘ia menyuruh orang memukul canang’

‘he asks someone to hit the small gong’

The constituent orang in data (7) double functions; they are (i) as the grammatical object of the V1 menyuruh, and (ii) as the grammatical subject of V2 memukul, meaning that the construction in data (7) is made up of two clauses, namely clause (7a) and clause (7b).

-

(7) a. ia menjuruh orang

(he asks someone)

105

-

b. orang memukul tjanang

(someone hits the small gong)

The following data shows the KVB menjuruh ÷X÷V2 as in data (7)

(8)

maka sultan

CONJ sultan

me-njerang

ACT-serang (Vtr)

mahmud me-njuruh

NAME ACT-suruh (Vtr)

mandjung (SM, 26.31:286) NAME

paduka paduka

tuan tuan

(9)

‘(maka) sultan mahmud menyuruh paduka tuan menyerang manjung’ ‘(so) Sultan Mahmud asks His Excellency to attack Manjung’ maka baginda-pun me-njuruh-kan orang pergi ke

CONJ baginda-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) orang pergi (Vint) PREP

madjapahit (SM, 14.8:73)

NAME

‘maka baginda pun menyuruh orang pergi ke majapahit’

‘so His Excellency also asks someone to go to Majapahit’

The suffix –kan attached to the verb menjuruhkan (9) functions to emphasize the existence of the nucleus argument, namely the grammatical object (Sasrasoeganda, 1986: 40;

Hollander, 1984: 65; van Wijk, 1985: 64) which is generic-indefinite in nature, namely orang, meaning that the existence of the suffix –kan in the verb menjuruhkan requires the existence of the grammatical object, namely orang, causing the construction which resembles (9a) is not found in BMK. The existence of the nucleus argument, namely orang as the grammatical object, is optional if there is no suffix -kan (9b).

-

(9) a. ?maka bagindapun menjuruhkan pergi ke madjapahit ‘?so His Excellency asks to go to Madjapahit.’

-

b. maka bagindapun menjuruh (orang) pergi ke madjapahit ‘so His Excellency also asks (someone) to go to Madjapahit’

-

(b) The KVB menjuruh ÷X+V2

(10) maka CONJ

sultan sultan

ber-tanja-kan

ACT-tanya (Vtr)

mahmud NAME mas'alah masalah

hendak hendak

me-njuruh

ke

ACT-suruh (Vtr) PREP

(SM, 32.11:105)

pasai

NAME

‘(maka) sultan mahmud hendak menyuruh (orang) ke pasai menanyakan masalah’ ‘(so) Sultan Mahmud intends to ask (someone) to go to Pasai to ask the problem. The constituent kepasai in data (10) is the non-nucleus argument, namely the adverb of place

which refers to the V1 menjuruh. Data (11) exemplifies the KVB menjuruh ÷X+V2 as in data (11).

106

-

(11) hatta maka sultan mahmud hendak me-njuruh ke-benua

CONJ sultan NAME hendak ACT-suruh (Vtr) PREP-negeri

keling mem-beli kain serasah (SM, 28.2:17)

NAME ACT-beli (Vtr) kain perca

‘(hatta maka) sultan mahmud hendak menyuruh (orang) ke negeri keling membeli kain perca’

‘(so) Sultan Mahmud intends to ask (someone) to go to Keling to buy kain perca’ (c)KVB menjuruh +X÷V2

-

(12) maka baginda-pun me-njuruh segera ber-lengkap

CONJ baginda-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) segera ACT-sedia (Vtr)

perahu (SM, 29.12:121) perahu

‘(maka) baginda pun menyuruh (orang) segera menyediakan perahu’

‘(so) His Excellency also asks (someone) to prepare a canoe immediately’

The constituent segera in data (12) is an adverb indicating the aspect of the V2 berlengkap.

Data (13) below exemplifies the KVB menjuruh+X÷V2 which uses the adverb indicating negation djangan for the V2 bersurat.

-

(13) kita me-njuruh djangan ber-surat (SM, 32.11:108)

1stpl ACT-suruh (Vtr) jangan ACT-surat (Vitr)

‘kita menyuruh (orang) jangan bersurat’

‘We ask (someone) not to write’

(d) The KVB menjuruh ÷X1+X2÷V2

-

(14) bubun-nja-pun me-njuruh ke malaka hendak

raja-PAR-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) PREP NAME hendak

minta surat sembah (SM, 13.1:3)

minta (Vtr) surat tanda tunduk

‘rajanya pun menyuruh (orang) ke malaka hendak meminta surat tanda tunduk’ ‘His Excellency also asks (someone) to go to Malaka to ask for the letter to surrender’

Data (14) shows that the non-nucleus argument, namely the adverb of place kemalaka refers to the V1menjuruh; however, the adverb modality hendak is the constituent which refers to the V2 minta.

Based on the characteristic of KPK, the only KVB menjuruh+V2 potentially becomes

KPK. There are two types of the KVB menjuruh+V2 which are identified as KPK; they are the KVB menjuruh+Vitr and KVB menjuruh+Vtr.

107

-

(a) The KPK menjuruh+Vitr

-

(15) orang me-njuruh lari supai itu (HA)

orang ACT-suruh (Vtr) lari (Vitr) serdadu PRON

‘orang menyuruh lari serdadu (india) itu’

‘Someone asks the Indian soldiers to run’

Data (15) contains the KPK menjuruh lari which functions as one predicate, which binds two nucleus arguments, namely the nucleus argument orang functioning as the grammatical subject and the noun phrase (NP) supai itu functioning as the grammatical object. The Vitr lari does not have any nucleus argument/grammatical subject as it has become an integral part of the KPK menjuruh lari. In KPK, the V1 menjuruh is the main verb determining the primary meaning (primary semantics), and the V2 lari is the light verb/vector verb/explicator verb functioning to express grammatical elements such as modality, aspect, tense, and modus (see Arka et al., 2007:187; Kroeger, 2004:255; Bukhari, 2009: 28; and Kosmas, 2007: 318). The semantic relation between the verbs in KPK expresses ‘purpose/expectation’.

Phonologically, the verbs forming KPK (15) are hypothesized as being within one unit of intonation (15a). In the bi-clausal construction, they are hypothesized as possibly having two pauses taking place after the matrix clause (16a-b).

-

(15) a. orang menjuruh lari supai itu∖

-

(16) a. orang menjuruh supai itu lari ×

-

b. orang menjuruh supai itu lari ‘someone asks the soldier to run’

The following data (data 17) exemplifies the KPK menjuruh+Vitr as data (15).

-

(17) ia hendak me-njuruh-kan lari tengku panglima besar

3T hendak AKT-suruh (Vtr) lari (Vitr) NAMA

itu (HA)

PRON

‘ia hendak menyuruh lari tengku panglima besar itu’ ‘He intends to ask Tengku Panglima Besar to run’

-

(b) The KPK menjuruh+Vtr

-

(18) maka baginda me-njuruh tutup pintu kota (SM, 1.13:91)

KONJ baginda AKT-suruh(Vtr) tutup (Vtr) pintu kota

’(maka) baginda menyuruh menutup pintu kota’ ‘(so) His Excellency asks to close the town door’

108

Data (18) contains the KPK menjuruh tutup functioning as (one) predicate. The predicate menjuruh tutup binds two nucleus arguments; they are the NP baginda functioning as the grammatical subject and the NP pintukota functioning as the grammatical object. The fact that the prefix meng- does not exist in the Vtr2 tutup strengthens the hypothesis that it is more accurate to analyze the KVB menjuruh+Vtr as in data (18) as KPK.

Phonologically, the verbs forming KPK (18) are hypothesized to be within one unit of intonation (18a). In the bi-clausal construction which is indicated by the use of the prefix meng- in V2, they are hypothesized to have a pause after the matrix clause (19).

-

(18) a. maka baginda menjuruh tutup pintu kota

-

(19) maka baginda menjuruh menutup pintu kota

‘so His Excellency asks to close the town door’

The data below exemplify the KPK menjuruh+Vtr as in data (18)

-

(20) maka baginda-pun me-njuruh panggil tun

CONJ baginda-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) panggil (Vtr) tuan

perpatih pandak (SM, 6.8:77)

pejabat NAME

’(maka) baginda pun menyuruh memanggil tuan pejabat pandak’

‘(so) His Excellency also asks to call Mr. Pejabat Pandak’

-

(21) jang diper-tuan me-njuruh bunuh hang

CONJ PAS-tuan ACT-suruh (Vtr) bunuh (Vtr) ART

tuah itu (SM, 16.2; 33.9)

NAME PRON

‘yang dipertuan menyuruh membunuh hang tuah itu’.

‘one who is considered the boss asks to kill Hang Tuah’

The KVB menjuruh which is identified as KKK has the characteristic of having a pausing mark between the V1 menjuruh and V2 in one construction, namely the bi-clausal construction in which the non-nucleus argument, namely the adverb can appear after the V1 menjuruh; the aspect, modality, and negation markers can appear prior to V2; the nucleus argument; in this case the nucleus argument or the grammatical subject of V1 can be the same as that of V2, or the nucleus argument or the grammatical subject of V1 can also be different from that of V2 expressing two events, depending on the verbs.

109

In general, the KVB menjuruh is KKK. All units of the KVB menjuruh+X+V2 are identified as KKK for the reason that all of its characteristics, or, one of its characteristics described above are or is fulfilled. Data (22) constitutes the KVB menjuruh+V2 which is identified as KKK, and can be used a reference to identify the KVB menjuruh identified as KKK.

-

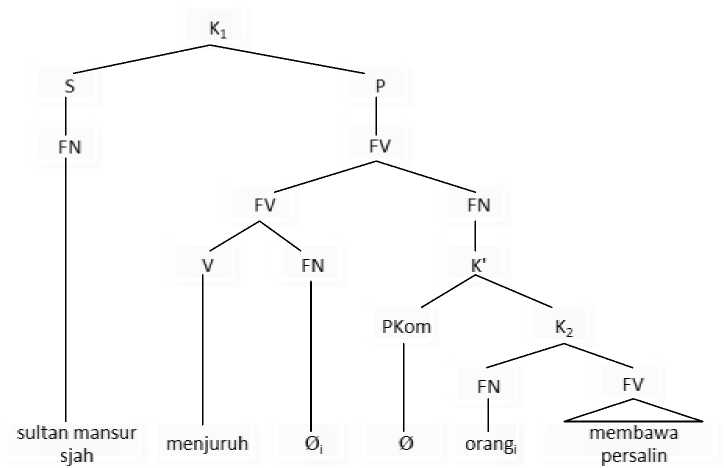

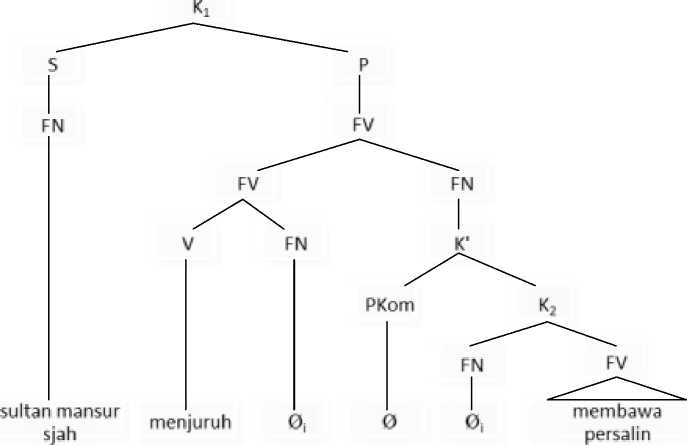

(22) sultan mansur sjah me-njuruh mem-bawa per-salin (SM, 16.6:100)

sultan NAMA AKT-suruh (Vtr) AKT-bawa (Vtr) N-salin

‘sultan mansur syah menyuruh (orang) membawa pesalin’ ‘Sultan Mansyur Syah asks (someone) to bring the childbirth’.

Data (22) shows that the Vi menjuruh and V2 membawa follows each other without any linguistic constituent between them. This construction is identified as a bi-clausal construction/KKK with an interpretation that the nucleus argument, namely the grammatical object of the V1 menjuruh, and the other nucleus argument, namely the grammatical subject of the V2 membawa are the generic indefinite NP orang whose existence is optional. This construction, according to van Valin (1984; 1990) and Durie (1997:228 and Artawa

(2010:152), is a bi-clausal construction formed through the nucleus juncture. Based on this analysis, it can be identified that data (22) is made up of two clauses (22a-b) which form the bi-clausal construction (22c).

-

(22) a. sultan mansur sjah menjuruh (orang) ‘Sultan Mansur Syah asks (someone)’ b. (orang) membawa persalin ‘(Someone) brings the childbirth’ c. sultan mansur sjah menjuruh orang membawa persalin ‘Sultan Mansur Syah asks someone to bring the childbirth’

Raising position from the lower position (object/patient) takes place in the shared argument orang in the bi-clausal construction (22c); in other words, the object/patient of the V1 menjuruh raises to the higher position and becomes the subject/agent of the V2 membawa (Noonan, 1998: 69—69).

Phonologically, it is hypothesized that there is a pausing mark between V1 and V2 as in the bi-clausal construction (22e) which is not intonated as in KPK (22f).

-

(22) d. sultan mansur sjah menjuruh membawa persalin

-

e. sultan mansur sjah menjuruh orang membawa persalin∖

-

f. *sultan mansur sjah menjuruh membawa persalin∖

‘Sultan Mansur Syah asks to bring the childbirth’

110

As a bi-clausal construction, the relation between the clauses in (22) shows the complementation relation. Clause (22a) is a matrix clause; however, clause (22b) is a subordinate/complement clause functioning as the object NP of the matrix clause. The semantic relation between (22a) and clause (22b) shows ‘purpose/expectation’ which can be

indicated by the complement marker (CM) supaja in BMK as reflected by data (23).

-

(23) aku pergi supaja djangan bel-adjar (HA)

1srs pergi (Vitr) PKom tidak ACT-ajar (Vitr)

‘aku pergi supaya tidak belajar’

‘I go in order not to learn’

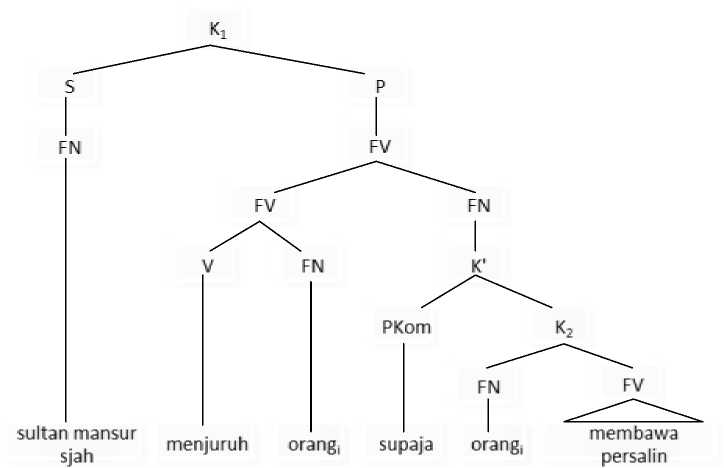

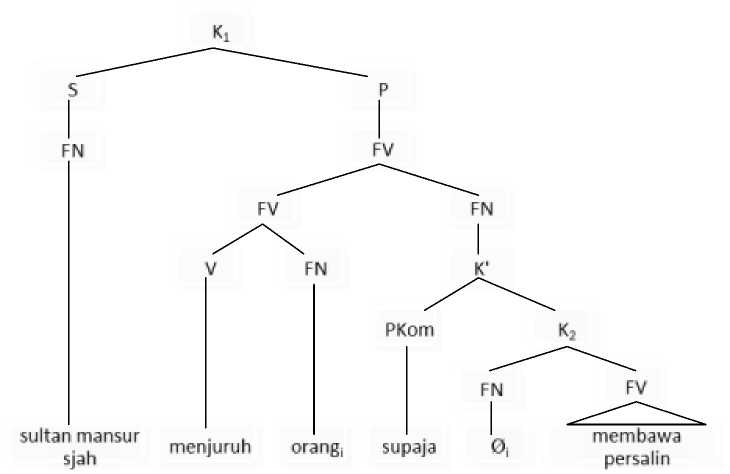

From the analysis using the transformational grammar, the basic structure of the surface structure of data (22) can be traced, as can be seen from the derivational process (22g)

illustrated in diagram (22h).

-

i. orang supaja orang membawa persalin

(22) g. sultan Mansur sjah menjuruh

-

ii. orang supaja membawa persalin

-

iii. orang membawa persalin

-

iv. membawa persalin

someone so that he/she

‘Sultan Mansyur Syah asks

carries the childbirth

-

ii. someone in order to carry the childbirth’

-

iii. someone to carry the childbirth’

-

iv. to carry the childbirth’

(22) h.i

111

(22) h.ii

112

(22) h.iii

(22) h.iv

Data (22) is derived from one basic form (22g.1) whose deep structure is illustrated in diagram (22h.i). (22g.ii) is formed by deleting the NP functioning as the subject, namely orang in the complement clause as it is the same as the NP functioning as the object, namely orang in the matrix clause as illustrated in (22h.ii). (22g.iii) is formed by deleting CM,

113

namely supaja and raising the NP functioning as the object, namely orang in the matrix clause to the position of the NP functioning as the complement clause as illustrated in diagram (22h.iii). (22g.iv) is formed by deleting the nucleus argument, namely orang functioning as the generic-infinitive grammatical subject in the complement clause as illustrated in (22h.iv). In BMK the construction (22g.i-ii)/diagram (22h.i-ii) only appears in the deep structure; however, the construction (22g.iii-iv)/diagram (22h.iii-iv) is a very common construction.

The following data (24—26) illustrate the KVB menjuruh-V2, which is identified as KKK as shown by data (22). All units of the KVB menjuruh+X+V2 as shown in (7)—(14) are identified as KKK.

-

(24) maka hang tuah me-njuruh turun (SM, 16.3:38)

CONJ ART NAME ACT-suruh (Vtr) turun (Vitr)

‘(maka) hang tuah menyuruh (orang) turun’ ‘(so) Hang Tuah asks (someone) to go down’

-

(25) maka bendahara me-njuruh ber-sadji nasi (SM, 22.4:23)

CONJ bendahara ACT-suruh (Vtr) ACT-saji (Vtr) nasi

’(maka) bendahara menyuruh (orang) menyajikan nasi’ ‘(so) the treasurer asks (someone) to serve rice’

-

(26) tuan-ku me-njuruh mem-bantu pahang (SM, 31.1:6)

tuan-PAR ACT-suruh (Vtr) ACT-bantu (Vtr) NAME

’tuanku menyuruh (orang) membantu pahang’

‘my boss asks (someone) to help Pahang’

The current study, in which the KVB mernjuruh was analyzed using the theory of complex predicate typology and theory of transformational grammar, shows that the KVB menjuruh is identified as KKK. The only the KVB menjuruh+Vitr and the KVB menjuruh+Vtr which are potentially identified as KPK. The KVB menjuruh+Vitr will be identified as KPK if the nucleus argument, namely the grammatical object, follows V2. The KVB menjuruh+Vtr will be identified as KPK if Vtr2 is not morphologically marked with the prefix meng-.

114

The KVB menjuruh can be classified into two; they are the KVB menjuruh+V2 and the KVB menjuruh+X+V2. Based on the grammatical characteristic of V2, the KVB menjuruh+V2 can be classified into two; they are the KVB menjuruh+Vitr and the KVB menjuruh+Vtr. The KVB menjuruh+X+V2 can be grouped into: the KVB menjuruh ÷X÷V2, the KVB menjuruh ÷X+V2, the KVB menjuruh+X÷V2, and the KVB menjuruh ÷X1+X2÷V2. Based on the theory of complex predicate typology, the only the KVB menjuruh+Vitr whose grammatical object functioning as the nucleus argument follows V2 and the KVB menjuruh+Vtr with Vtr2 which is not morphologically marked by the prefix meng- are identified as KPK. Based on the theory of transformational grammar, all units KVB menjuruh, except the ones identified as KPK, are identified as KKK.

The syntactical analysis of the KVB menjuruh in this article is highly specific in BMK. It is suggested that the researchers who are interested in Malay language and literature should further explore any syntactical and discursive aspects.

REFERENCES

Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. "Serial Verb Constructions in Typological Perspective". Dalam Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y dan RMW Dixon (eds). 2004. Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross Linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arka, I Wayan; Jeladu Kosman, I Nyoman Suparsa. 2007. Bahasa Rongga: Tata Bahasa Acuan Ringkas. Jakarta: Penerbit Universitas Atmajaya.

Artawa, Ketut. 1998. “Bahasa Indonesia: Sebuah Kajian Tipologi Sintaktis”. Laporan Penelitian Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Udayana. Denpasar.

Artawa, Ketut. 2004. Balinese Language: A Typological Description. Denpasar: CV Bali Media Adhikarsa.

Awang, Halimah Wok. 1988. ”Teori Standard dalam Perkembangan Aliran Transformasi-Generatif”. Di dalam Karim (penyunting). 1988. Linguistik Transformasi Generatif: Suatu Penerapan pada Bahasa Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

Bukhari, Nadeem. 2009. "A Comparative Study of Gojri Double Verb Constructions" dalam Language in India. Volume 9, 1 January www.languageindia.com.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structure. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspect of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, Mass: MIT

Collins, James T. 2005. Bahasa Melayu Bahasa Dunia: Sejarah Singkat. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Dardjowidjojo, Soenjono. (penyunting). 1987. Linguistik Teori & Terapan. Jakarta: Lembaga Bahasa Universitas Katolik Atma Jaya.

115

Datoek Besar, R.A.; R. Roolvink. 1953. Hikajat Abdullah. Djakarta: Penerbit Djambatan

Dol, Philomena. 1996. “Sequences of Verbs in Maybart” dalam Ger P. Reesink. Nusa: Linguistic Studies of Indonesian and Other Languages in Indonesia Volume 40. Jakarta: Lembaga Bahasa Universitas Katolik Atma Jaya.

Durie, Mark. 1997. "Grammatical Structures in Verb Serialization." Dalam Alsina Alex Joan Bresnan, dan Peter Sells (ed). Complex Predicates. 289-354. Stanford, California: CSLI.

Hollander, J.J. de. 1984. Pedoman Bahasa dan Sastra Melayu. Jakarta: PN Balai Pustaka.

Karim, Nik Safiah (penyunting). 1988. Linguistik Transformasi Generatif: Suatu Penerapan pada Bahasa Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

Karim, Nik Safiah. 1988. Linguistik Transformasi Generatif. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendiddikan Malaysia.

Kosmas, Jeladu. 2007. “Klausa Bahasa Rongga: Sebuah Analisis Leksikal-Fungsional.” Disertasi Program Pascasarjana Universitas Udayana. Denpasar.

Kroeger, Paul R. 2004. Analysing Syntax: a Lexical-Functional Approarch. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Lapoliwa, Hans. 1990a. Klausa Pemerlengkapan dalam Bahasa Indonesia. Seri ILDEP. Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

Lapoliwa, Hans. 1990b. "Deretan Verba: Frasa atau Kalusa?". Dalam Majalah Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia. Tahun 8 No. 2 Desember 1990.

Mas Indrawati, Ni Luh Ketut. 2012. “Konstruksi Verba Beruntun Bahasa Bali (Kajian Sintaktis dan Semantis”. Disertasi Program Studi Linguistik, Program Pascasarjana Universitas Udayana. Denpasar.

Menick, Raymond H. 1996. “Verb Sequences in Moi” dalam Ger P. Reesink. 1996. Nusa: Linguistic Studies of Indonesian and Other Languages in Indonesia Volume 40. Jakarta: Lembaga Bahasa Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya.

Pradnyayanti, Luh Putu Astiti. 2010. “Konstruksi Verba Beruntun Bahasa Sasak Dialek Ngeto-Ngete”. Tesis Program Studi Linguistik, Program Pascasarjana Universitas Udayana. Denpasar.

Sariyan, Awang. 1988. ”Penerapan Teori Linguistik Transformasi Geberatif dalam Analisis Teks: Suatu Kajian Kesinambungan Bahasa”. Di dalam Karim (penyunting). 1988. Linguistik Transformasi Generatif: Suatu Penerapan pada Bahasa Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

Sasrasoeganda, K. 1986. Kitab jang Menyatakan Djalannja Bahasa Melajoe. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

Senft, Gunter. 2008. Serial Verb Constructions in Austronesian and Papuan Languages. Australia: Pacific Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies.

Silitonga, Mangasa. 1990. ”Tata Bahasa Transformasional Sesudah Teori Standar” dalam Bambang Kaswanti Purwo (Penyunting). PELLBA (Pertemuan Linguistik Lembaga Bahasa Atma Jaya) 3. Jakarta: Lembaga Bahasa Universitas Katolik Atma Jaya.

Situmorang, T.D. dan A. Teeuw dengan Bantuan Amal Hamzah. 1958. Sedjarah Melaju (edisi terbitan Abdullah ibn Abdulkadir Munsji). Cetakan ke-2. Jakarta: Penerbit Djambatan.

116

Subiyanto, Agus. 2010. “Konstruksi Verba Beruntun dalam ‘Nona Koelit Koetjing’”. Dalam Magister Linguistik PPs Undip Semarang, 6 Mei 2010. Semarang.

van Staden, Miriam dan Ger Reesink. 2008. “Serial Verb Constructions in a Linguistic Area” dalam Gunter Senft (Ed.). Serial Verb Constructions in Austonesian and Papuan Languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics RSPAS ANU.

van Wijk, D. Gerth. 1985. Tata Bahasa Melayu. Jakarta: Penerbit Djambatan.

117

Thanks are expressed and a word of appreciation should go to Prof. Dr. I Nengah Sudipa, M.A.; Prof. Dr. Aron Meko Mbete; Prof. Dr. Made Budiarsa, M.A.; Prof. Dr. Drs. Ida Bagus Putra Yadnya, M.A.; and Prof. Dr. I Nyoman Kardana, M.Hum. for their criticism and suggestions.

118

Discussion and feedback