CODE-CROSSING: HIERARCHICAL POLITENESS IN JAVANESE

on

E-Journal

CODE-CROSSING: HIERARCHICAL POLITENESS IN JAVANESE

Majid Wajdi

State Polytechnic of Bali

Email: mawa2id@yahoo.com

I Ketut Darma Laksana

Doctorate Program in Linguistics, Faculty of Letters, Udayana University

I Made Suastra

Doctorate Program in Linguistics, Faculty of Letters, Udayana University

Made Budiarsa

Doctorate Program in Linguistics, Faculty of Letters, Udayana University

ABSTRACT

Javanese is a well known for its speech levels called ngoko ‘low’ and krama ‘high’ which enable its speakers to show intimacy, deference, and hierarchy among the society members. This research applied critically Brown and Gilman (1960)’s theory of terms of address to analyze the asymmetrical, factors which influence, and politeness of the use of speech levels in Javanese.

Method of observation, in depth interview, and document study were applied to collect the data. Recorded conversation was then transcribed into written form, classified and codified according to the speech levels, and analyzed using politeness system (Scollon and Scollon, 2001) and status scale (Homes, 2001).

The use of speech levels shows asymmetric communication: two speakers use two different codes, i.e. ngoko and krama because of power (+P) and with/without distance (+/-D), and it is the reflection of hierarchical politeness. The asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama by God and His Angel, God and human beings strongly explicated the asymmetrical communication between superiors and inferiors. The finding of the research shows that the use of ngoko and krama could present the phenomena of code-switching, code-mixing, and the fundamental phenomenon is ‘code-crossing’. It is concluded that hierarchical politeness in Javanese is ‘social contract’ i.e. the acknowledgment of the existence of high class (superior) and low class (inferior) implemented in ‘communications contract’ using speech levels of the Javanese language in line with status scale. Asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama indexed inequality, hierarchy, and harmony

Key words: asymmetric, code-crossing, hierarchy, Javanese, speech levels

The Javanese language is widely known for its speech levels: ngoko ’low’ and krama ’high’ which enable its speakers to show intimacy, deference, and hierarchy among its speakers. Geertz (1981) as paraphrased by Fasold (1990: 34; cf. Hudson, 1982) admitted that “Javanese way of showing deference and intimacy by means of language is much more elaborate than any examples in European languages” which only have terms of address (T/V) (cf. Brown and Gilman, 1960) and even the languages known in the world (Berman, 1998: 12; cf. Keeler, 1987; cf. Smith-Hefner, 1988: 537). T/V in Javanese is an integral part of ngoko and krama speech levels. Because of its ngoko and krama speech levels, Javanese is classified as a diglossic language (Sadtono, 1972; Errington, 1998).

Interestingly, Javanese diglossia could not be simplified to be similar to other diglossias. Sneddon (2003) identified diglossia in Indonesian language in which standard Indonesian as H(igh) variation and non-standard Indonesian as L(ow) variation. Anderson (1966; 1990 in Jurrien, 2009: 16; Anderson, 1992; cf. Samuel, 2008) analysed standard Indonesian (H) using high speech level (krama) and non-standard Indonesian (L) is similar to low speech level (ngoko). Errington (1986) disagreed with Anderson’s model of analysis and it is reinforced by Samuel (2008) that Errington has deep understanding of diglossia. Diglossia and Javanese diglossia could not be simplified to be either similar to bilingualism. That is why the phenomena in Javanese is not exactly similar to the phenomena in bilingualism, because diglossia is different from bilingualism (Romaine, 1985) which was associated with code-switching and or code-mixing as shown in the previous researches, as examples, Sadtono, (1972), Markhamah (2000), Rahardi (2001) and Rokhman (2004). In this research the theory of terms of address (T/V) (cf. Rubin (1972; cf. Schiffman, 1997: 213) is extended and critically applied to analyze the use of ngoko ‘low’ and krama ‘high’ in Javanese.

Based on the background above, the use of speech levels in Javanese constitutes the research problems of the study, namely (1) what pattern of asymmetrical use, (2) what factors, and (3) what politeness of the use of speech levels by speech community of Magelang Central Java during their daily life. The research is meant to describe, analyze,

and interpret (1) the patterns of asymmetrical use, (2) the factors which influence, and (3) politeness of the use of ngoko and krama speech levels of Javanese.

In theory, the research hopefully gives, i.e. (1) a new understanding of the theory, (2) reinterpretation of terms of address, (3) model of the theory of modification. The research is focused on the asymmetrical communication: asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama speech levels.

2 Research Method

The data of the research was collected through observation, in depth interview, and document study. The recorded data were then transcribed, classified or codified according to Javanese speech levels, analysed by terms of address or T/V (Brown and Gilman, 1960), politeness systems (Scollon and Scollon, 2001), and status scale (Holmes, 2001).

The discussion, analysis, and interpretation include how the speech levels of Javanese are used and employed by its speakers to fulfill daily needs of communication and interaction. The discussion here is focused on asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama, the factors which influence, and politeness of the use speech levels of Javanese.

The following text 1 is a short message (SMS) sent by first participant (P1) to second participant (P2) as presented below.

Text 1

(01) P1: Uni, kowe melu tes CPNS pa ora?

‘Uni, did you join a test of civil servant candidate or not?’

(02) P2: Ora mbak. Wong ora ana lowongan sing pas karo ijazahku.

SAMPEYAN melu pa?

‘No, sister. There is not any position in line with my certificate. (How about you) Did you join it?)’

In text 1 the participants use ngoko to speak to each other. The difference is that the first speaker (P1) uses term of address kowe (tu) ‘you’ but the second speaker (P2) employs SAMPEYAN (vous). The first speaker (P1) called her younger sister using her

younger sister’s name only (name), but the second speaker (P2), as younger, addresses her elder sister using kin term or title (plus name) mbak to show her respect to her elder sister. Although all speakers in Text 3 use ngoko to each other, but P2 employs high term of address sampeyan ‘you’ to address her elder sister (P1). On the other hand, P1 uses low term of address kowe ‘you’ to her younger sister (P2). This phenomenon is not by accident and a random linguistic behavior. The participants consciously control and consider carefully choosing and using different codes (terms of address). Seniority consideration which leads to P2 in Text 1 to choose high term of address sampeyan ‘you’ to her elder sister (P1), who is older than her. On the one hand, P1 employs low term of address kowe ‘you’ to her younger sister (P2).

The following text is a phone conversation between a father (around 70 years old) and his daughter (30 years old).

Text 2

This is a dialogue between P1 (father) and P2 (P1’s daughter). Capital transcription refers to krama and non-capital transcription is ngoko.

(01) P1: Seka ngomah apa seka sekolahan kowe?

‘(Are you calling) from home or from (your daughter’s) school?’ (02) P2: SAKING GRIYA. KULA MENAWI DINTEN SETU MBOTEN

NDEREK

‘From home. I, if (it is) Saturday, do not follow (her husband to pick her daughter from school)’

(03) P1: Oh ngono to

‘Oh, like that’

(04) P2: NGGIH, MENAWI SETU MAS MIDUN LIBUR, TERAS MAS

MIDUN INGKANG WONTEN MRIKA

‘Yes, if (it is) Saturday brother Midun is off, then he is there (to pick the children from school)’

(05) P1: Saiki kowe nang ngomah?

‘Now, you are at home?’

-

(22) P2: NGGIH MBOTEN MENAPA-MENAPA. WONTEN KABAR

MENAPA PAK?

‘Yes, there is not any problem. How are you, father?’

Text 2 is a dialogue between a father (P1) and his daughter (P2). The father (P1) completely uses ngoko, but his daughter definitely employs krama. It is important to underline here that the father uses the second pronoun kowe (tu) ‘you’ to his daughter, as seen in (01) and (05), but his daughter, on the other hand, employs (ba)pak ‘Dad’ (literally

’Sir/Mr’) in (22). Of course, it is a very interesting phenomenon to observe. Daily communication between a father and his daughter (and also all his children, all are married, in the family) is conducted in Javanese using two different speech levels. This (Text 2) is an example of a conversation between two participants in which they choose and use fundamentally two different codes, low code (ngoko) and high code (krama). This phenomenon shows us that there is inequality found in language use.

Text 3

Surat Albaqarah (2): 67, 68 (Taufiq, 1995: 24). The English translation was based on Dawood (1995: 16).

Prophet (Musa): Satemene Allah iku DHAWUH marang sira kabeh supaya nyembelih sapi wadon (2: 67)

‘Verily, Allah commands you to sacrifice a cow’

Human: DHUH NABI MUSA, PUNAPA PANJENENGAN DAMEL

GEGUJENGAN DHATENG KULA SEDAYA (2: 67) ‘Are you making game of us?’

Human: DHUH NABI MUSA, KULA ATURI NYUWUN DHATENG

PANGERAN PANJENENGAN KANGGE KULA SEDAYA, SUPADOS PANJENENGANIPUN NERANGAKEN DHATENG KULA SEDAYA, LEMBU PUNAPA PUNIKA (2: 68)

‘Call on your Lord to make known to us what kind of cow she shall be’.

Prophet ( Musa): Satemene Allah NGENDIKA, yen sapi wadon mau dudu sapi tuwa lan uga dudu sapi enom, nanging tengah-tengah antarane iku. Mula sira kabeh padha nendhakna apa kang diDHAWUHake marang sira kabeh (2: 68)

‘Verily your Lord says: Let her neither an old cow nor a younger heifer, but in between. Do, therefore, as you are bidden’.

Text 4 QS

Al Imran (3): 45 and 46, 47

Gabriel: He Maryam, satemene Allah nggembirakake sira (kanthi lahire

sewijining putra kang dicipta) kanthi kalimat (kang teka) saka Pengerane, jenenge Al-Masih Isa anak Maryam, sewijining kawulane Allah kang kaparingan keluhuran ing donya lan akhiran,

lan klebu golongane wong-wong kang cedhak marang Allah. Lan dheweke omong karo manungsa ana ing sajerone iyunan lan nalika wis diwasa, lan dheweke salah sijine wong-wong kang saleh-saleh

‘O Maryam (Mary)! Verily, Allah gives you the glad tidings of Word [“Be!”- and he was! i.e. ‘Iesa (Jesus) the son of Maryam (Mary) from Him, his name will be the Messiah ‘Iesa (Jesus), the son of Maryam (Mary), held in honour in this world and this world and in the Hereafter, and will be one of those who are near to Allah’

Maryam: DHUH GUSTI PANGERAN KULA, KADOS PUNDI KULA

SANGED GADHAH ANAK, KAMANGKA KULA DERENG NATE DIPUN SENGGOL DENING TIYANG JALER SINTEN KEMAWON

‘O my Lord! How shall I have a son when no man has touched me?’

Text 4 is a dialogue between Angel Gabriel and Maryam (Mary). In the name of Allah (God), Angel Gabriel informed Maryam (Mary) that she will soon have a baby called Iesa. Of Course Maryam (Mary) was very surprised because she was unmarried. How can a spinster get a baby of her? The Angel Gabriel spoke using ngoko and Maryam (Mary) responded it in krama. In this dialogue Angel Gabriel is superior and Maryam (Mary) is inferior.

The data of asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama were collected through document study i.e. Javanese translation of Al Quran (Taufiq 1995: 7; QS 2: 11). Text 5 is a dialog between God and human being. God reminds human being not to commit evel in the land during their life. The English translation is based on Dawood (1995: 11).

Text 5

-

(1) God: Sire kabeh aja padha gawe kerusakan ana ing bumi”

‘Do not commit evil in the land’

-

(2) Human: SAYEKTOSIPUN KULA SEDAYA PUNIKA TIYANG-TIYANG INGKANG DAMEL KESAENAN

‘We do nothing but good’

The above quotation is a dialog between God and human being. God reminded human being (man) who likes to make disharmony on earth not to do so. The original dialog is in Arabic which was then translated into Javanese. God, when speaking to human

being was translated into ngoko, but man (human being) responds to it in krama (Taufiq, 1995: 7) (ngoko is written in non-capital and krama is in italic capital). According to the social rule in the Javanese society, inferiors are obliged (as well their rights) to speak in krama but superior has rights and obligation to use ngoko. The dialog between God and human is clearly seen that superior (God) speaks ngoko “downward” to inferior but inferior (human) speaks krama “upward” vertically to superior. Asymmetrical communication between God and human being explicitly shows “code-crossing” communication.

Why do the participants choose to use two different codes? Why does the first speaker (P1) use ngoko while the second speaker (P2) employs krama as a means of communication during their daily life? Why do they not use ngoko only or krama to communicate to each other? Why do the participants not use and employ krama to each other as a means of interaction and communication during their life? It is impossible for them to use two different codes, the first speaker uses ngoko and the second speaker employs krama, if there is not any factor and reason. Two participants when using ngoko and krama indicate that they have different social statuses: ngoko user has higher status than krama user, or krama user has lower status than ngoko user. Power difference is symbolized by (+P) ‘plus power’. Social hierarchy is expressed using two different speech levels, i.e. ngoko and krama speech levels. The asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama is an index of inferiority of ngoko user and krama is an index of superiority of its user.

A father, in general, has close relationship with his children, but he has power over them. That is why it is symbolized by (+P;-D) ‘plus power’ and ‘minus distance’. In this context, the choice of different speech levels between a father and his children is governed by the factor of power (+P), not because of social distance since a father has a close relationship with his children. On the other hand, an uncle who lives in the other city or village, could be said that he has power (+P) as well as distance (+D) since he rarely meets his brother’s or sister’s children. Here the factor of distance (+D) could be added to complete the factor of power (+P) in driving the choice of speech levels in Javanese.

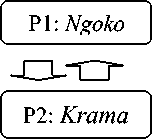

If the use of ngoko and krama by two participants is identified as a marker of hierarchy and the meaning is inequality between the participants, the next question which could be delivered is whether there is politeness in asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama? Is there any politeness in the use of ngoko and krama? Is the only the speaker who uses krama that could be classified as a polite speaker? Is the speaker who employs krama that could be seen as a polite speaker? Who is showing politeness, the speaker of ngoko or the user of krama? Are they, both the speaker of ngoko and krama user, showing politeness in language use? The question is what kind of politeness can be inferred from the use of ngoko and krama? Is it polite enough for the speaker who uses ngoko speech level, while the other speaker employs krama? Or is just the speaker of krama showing politeness? Are all the speakers in Text 1, 2, 3, and 4, identified to be polite? Since it is asymmetrical dyadic communication, the politeness shown is called hierarchical politeness. Hierarchical politeness system is illustrated below (cf. Wajdi 2009b; 2010a/b; 2011a/b). Ngoko, in asymmetrical use, is an index of superiority of the speakers and krama is an index of inferiority of the users. In hierarchical politeness the participants know each other and respect social differences that put someone in ‘higher’ position (superordinate) and the other in ‘lower’ position (subordinate). This is a face system in which a father speaks ‘downward’ to his children but the children speak ‘upward’ to their father (Text 4).

Figure 1 Hierarchical Politeness in Javanese

The main characteristic hierarchical politeness system is the difference in status (Cf. Geertz, 1981) or power (cf. Scollon and Scollon, 2001) of the participants, and for the sake of it, the symbol (+P) ‘plus power’ is used. Superior, of course, has high status and inferior has low status. Politeness involves the use of language which is marked by clear status of the participants (cf. Holmes, 2001). In Javanese, the choice of appropriate codes is the reflection of the speakers’ assessment of the relation status of the participants. The factor of code choice, including the use of appropriate term of address, is age, family

relationship, and social status shown in one’s profession and education. The superiority of a speaker is shown by the use of low code (ngoko) and the inferiority of a participant is reflected by the use of high code (krama).

The type of asymmetrical communication using Javanese speech levels formed when two speakers using ngoko and krama to speak to each other is identified as hierarchical politeness. The relationship between two asymmetric speakers, which is implemented using ngoko and krama to speak to each other during their daily life is principally a reflection of politeness. The factor of inequality, (it is symbolized by (-P) ‘minus power’ and whether intimate or non-intimate (+/-D) ‘plus/minus distance’) is the main factor of the use of ngoko and krama, which reflects hierarchical politeness. Asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama is an index of superiority of ngoko user and inferiority of krama speaker.

The phenomenon of the use of two different codes, i.e. ngoko and krama codes by two unequal speakers is identified as “code-crossing”. The dialogues in Text 1, Text 2, and Text 3, and Text 4 show that the first participant (P1) uses ngoko and the second participant (P2) employs krama. Such a phenomenon is an interesting phenomenon of language use which reflects inequality between the participants. The inequality of the participants which is implemented by the use of low (ngoko) and high codes (krama) is called “code-crossing”

Asymmetrical communication in stratified society and using language stratification, seen from the use of the code, is called code-crossing. When two unequal participants: superior-inferior, senior-junior, boss-employee, teacher-student have to communicate to each other using language code, i.e. superior uses ngoko and inferior employs krama is called code-crossing. If it is contrasted, the use of term of address kowe ‘you’ by an elder sister (brother) and sampeyan ‘you’ by a younger sister (brother) as seen in Text 1, it is best called “code-crossing” (Wajdi, 2009, 2010a/b, 2011a/b). The phenomenon of code-crossing is not merely communication strategy, but it is a kind of

“social contract”, i.e. an acknowledgment of the existence of low and high class which is implemented in communication contract using their own language stratification. As it is normally a contract, there is right and obligation which have been agreed by the participants. Social contract that has been made: superior (e.g. elder sister/brother, father) uses low term of address kowe ‘tu’ and inferior (younger sister/brother, children) employs sampeyan or panjenengan ‘vous’. The use of term of address kowe ‘you’ and sampeyan by two participants shows “crossing” phenomenon; that is why it is called “code-crossing”. The use of T vs. V by two participants also presents “crossing” phenomenon that is why it is called “code-crossing”.

Code-crossing, in a society with social stratification, is a social contract made and agreed by the members of society as an acknowledgment of the existence of two social groups or classes: superior and inferior. As part of society members and as social human beings, they could not get rid of communicating to each other. Communication behaviour using speech levels in Javanese is well patterned. In asymmetrical communication, the participants use ngoko and krama utterances to each other. It could be said that communication behavior in Javanese speech community is a stable not temporary phenomenon. Once two participants use two different codes, the first participant uses ngoko and the second one employs krama, they will maintain it for ever as far as they communicate using Javanese. Once the participants build an asymmetrical communication, they will treat themselves as an inferior and superior. Once they agree to be superior and the other participant is inferior, they will build an asymmetrical communication: a superior uses ngoko and an inferior employs krama every time they communicate in Javanese. In code-crossing, it is agreed that a superior has rights as well as obligations to use ngoko and the inferior’s rights and obligations is to use krama. Seen from the communication point of you, code-crossing could be stated as communication contract between superior (who has rights and obligation to use ngoko) and inferior (has rights and obligation to employ krama). Code-crossing, if it is seen from conversation point of you, is conversatinal contract between superior and inferior as an acknowledgment of the existence of social stratification using speech stratification in the language implemented by the use of ngoko and krama utterances.

Code-crossing, if it is seen from inferior participant’s point of you, is inferior group’s empowerment before superior. The existence of two groups, called superior and 10

inferior, is separated by a great wall. By having code-crosing, inferior group is allowed to trespass the border of superior’s territory. In order to to cross the border and great wall, the inferior has to possess and fulfill a certain qualification approved by the territory’s owner or superior. The requirements which is both agreed is the use of krama as inferior’s rights and obligation, and superior’s rights and obligation is the use of ngoko. The use of krama, for inferior, is a kind of ”driving licence” in order to be able to enter an exclusive territory of superior. Krama utterance, when it is used by inferior before superior, is a kind of ”password” which could be employed to open and access superior’s territory. The use of ngoko and krama codes when they are used in code-crossing communication is a kind of ”personal identification code”, who the participants are and what roles of social class they perform.

They, of course, have to make a kind of agreement: superior has a right to use ngoko and inferior’s obligation is to use krama every time they are involved in a communication. Such a phneomena is not a temporary phenomena but a really stable or even a permanent phenomena. Once a superior uses low code to address an inferior and the inferior employs high code to speak to superior, they will maintain it for ever as far as they are communicating in Javanese. Once they make an agreement (or social contract) they will be consistenly committed to following what they have agreed. The social contract they have made and agreed in the speech community is that superior, senior, or older person has rights and obligation to use ngoko and krama is inferior’s (junior, or younger person) rights and obligation. It is superior’s rights as well as obligation to use Tu or kowe ’you’ to inferior and inferior’s rights as well as obligation is to employ Vous or sampeyan or panjenegan ’you’. It could be concluded that superior has to use ngoko and inferior has to employ krama every time they communicate to each other. In asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama, the speakers are even obligated (or have rights and obligations) to increase linguistic or communicative differences. Superior speaks “downward” vertically to inferior, but inferior speaks vertically “upward” to superior.

The description of the use of speech levels shows three communication patterns. Firstly, the symmetrical exchanges of ngoko in which the participants use ngoko to communicate to each other because of equality and intimacy (-P); (-D) and it is the 11

reflection of solidarity politeness. Secondly, the symmetrical exchanges of krama, in which the participants make a decision to choose and use krama to communicate everything during their life. Thirdly, the asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama in which the participants make an agreement to use two different codes, i.e. ngoko and krama.

The analysis and interpretation of the use of speech levels were driven by equality and intimacy factors, equality without intimacy, and inequality. Firstly, the symmetrical exchanges of ngoko reflects solidarity politeness, because of equality (-P) and intimacy (D). Secondly, the symmetrical exchanges of krama reflects deference politeness because of equality in distance (-P;+D). Thirdly, the asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama reflects hierarchical politeness which was driven by inequality or hierarchy (+P;+/-D).

The analysis of the use of speech levels yielded asymmetrical politeness system in Javanese. The asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama reflects hierarchical politeness. The communication types using speech levels are well patterned, and they are supported by factors, and yielded types of hierarchical politeness; it could be concluded that politeness in Javanese is ”social contract”, i.e. an acknowledgment of the existence two social classes: high (superior) and low classes (inferior) which is implemented in ”communication contract” using speech levels of the language based on the status scale of the participants in line with their rights and obligations.

The use of speech levels, the factors which influence, the politeness shown both in symmetrical exchanges ngoko, symmetrical exchanges krama and asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama are still relevant to maintain in the Javanese society, as shown in the following reason.

Asymmetrical exchanges of ngoko and krama gives emphasis on inequality and hierarchy plus harmony. Asymmetrical use of ngoko and krama is an acknowledgement of

the existence of high (superior) and low classes (inferior), but harmony not disharmony becomes the priority then it is called hierarchical politeness.

6. Acknowledgements

In this opportunity, the writer would like to thank those who have contributed to this study such as Prof. Dr. I Ketut Darma Laksana, M.Hum., as the main supervisor, Prof. Drs. I Made Suastra, Ph.D., as co-supervisor I, Prof. Dr. Made Budiarsa, M.A., Ph.D., as co-supervisor II, and Prof. Drs. Ketut Artawa, M.A., Ph.D., Prof. Dr. I Wayan Pastika, M.S., Prof. Dr. I Wayan Simpen, M.Hum., Dr. Ni Made Dhanawaty, M.S., and Prof. Dr. Fathur Rokhman, M.Hum., as the examiners for their critical and constructive input for the improvement of this dissertation.

A word of appreciation should also go to the Rector of Udayana University and the Director of Post Graduate School of Udayana University for the opportunity and facilities provided.

References

Anderson, B.R.O’G.1966. “The Language of Indonesian Politics”, Indonesia. – no.1, April, pg. 89—116.

Anderson, B.R.O’G.1992. Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia. New York: Cornell University Press.

Anderson, B.R.O’G.1996. “Sembah-Sumpah, Politik dan Kebudayaan Jawa” Dalam Latif, Yudi dan Idi Subandy Ibrahim (ed.).1996. Bahasa dan Kekuasaan: Politik Wacana di Panggung Orde Baru. Bandung: Mizan.

Anderson.B.R.O. 1990. “Professional Dreams: Reflections of two Javanese Classics” republished in Anderson. 1992. Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia. New York: Cornell University Press.

Berman, L. A. 1998. Speaking Through the Silence: Narratives, Social Conventions, and Power in Java. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bonvillain, Nancy. 2003. Language, Culture, and Communication: The Meaning of Messages. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc. 4th edition.

Brown, R. and A. Gilman. 1960. “The Pronoun of Power and Solidarity”, in Sebeok, T.A.

(Ed.). Style in Language. MIT Press.

Dawood, NJ. 1994. The Koran. England: The Penguin Group.

Errington, J. J. 1986. “Continuity and Change in Indonesian Language Development”, Journal of Asian Studies. – No. XLV-2, February, pg. 329—353.

Errington, J. J. 1998. Shifting Languages, Interaction and Identity in Javanese Indonesia.

United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Fasold, Ralph. 1990. Sociolinguistics of Language. USA: Basil Blackwell Inc.

Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. “Diglossia”. Word, vol. 15.

Fishman, J.A. (Ed.). 1968. Advances in the Sociology of Language. Paris: The Hague.

Volume1.

Fishman, J.A. 1967. “Bilingualism with and without Diglossia; Diglossia with and without Bilingualism”. Journal of Social Issues 23: 29—38.

Fishman, J.A. 1972. ”Varieties of ethnicity and Varieties of Language consciousness”. In Dil, A.S (Ed.). Language and Socio-cultural Change: Essay by J. Fishman. Standford: Standford University Press.

Fishman, J.A. 1980. “Bilingualism and Biculturalism as Individual and Societal Phenomena”. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1: 3—17.

Geertz, Clifford. 1981. Abangan, Santri, Priyayi Dalam Masyarakat Jawa. Jakarta: Pustaka. Penterjemah: Aswab Mahasin.

Gunarwan, Asim. 2007. “Implikatur dan Kesantunan Berbahasa: Beberapa Tilikan dari Sandiwara Ludruk”, Dalam Nasanius, Yassir (Ed.). PELBBA 18. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. hal 85—119.

Halliday, M.A.K. and Ruqaya Hasan. 1985. Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-semiotic Perspective. Victoria: Deakin University.

Harjawiyana and Supriya. 2009. Kamus Unggah-ungguhing Bahasa Jawa. Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

Hudson. R.A. 1982. Sociolinguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ibrahim, A.S. 1993. Kapita Selekta Sosiolingustik. Surabaya: Usaha Nasional.

Jurriëns, Edwin. 2009. From Monologue to Dialogue: Radio and Reform in Indonesia.

Leiden: KITLV Press. Could be accessed at: www.kitlv.nl

Kartomihardjo, Suseno. 1978. Ethnography of Communication: Code in East Java. Canberra: The Australian National University Press.

Keeler, Ward. 1987. Javanese Shadow Plays, Javanese Selves. Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press.

Markhamah. 2000. Bahasa Jawa Keturunan Cina di Kota Madya Surakarta. Yogyakarta: PPs. UGM. Disertasi. Tidak Diterbitkan.

Poedjosoedarmo, Soepomo. 1968. “Wordlist of Javanese Non-Ngoko Vocabularies”.

Indonesia, N0. 6, October 1968. source

http://cip.cornell.edu/DPub?service=UIandversion=1.0&verb=Display&page=toc& handle=seap.indo/1107139648

Poedjosoedarmo, Soepomo. 1970. “Javanese Speech Levels”. Indonesia, No. 7. Source: http://www.jstor.org/pss/3350711

Purwoko, Herujati. 2008a. Jawa Ngoko: Ekspresi Komunikasi Arus Bawah. Jakarta: Indeks.

Rahardi, Kunjana. 2001. Sosiolinguistik, Kode dan Alih Kode. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar.

Rampton, Ben, 1997. “Language Crossing and the Redefinition of reality: Implications for research on Code-switching community”. Source:

(http://www.kcl.ac.uk/schools/sspp/education/research/groups/llg/wpull4l.html)

Rokhman, Fathur. 2004. Pemilihan Bahasa Dalam Masyarakat Dwibahasa: Kajian Sosiolinguistik di Banyumas. Yogyakarta: PPs.UGM. Disertasi. Tidak Diterbitkan.

Romaine, Suzanne. 1995. Bilingualism. USA: Blackwell Publishers. 2nd edition.

Rubin, J. 1972. “Bilingual usage in Paraguay”, In J.A. Fishman (ed.), Advanced in the Sociology of Language, vol. 2, 512—530. The Hague: Mouten.

Sadtono, Eugenius. 1972. Javanese Diglossia and Its Pedagogical Implications. Austin: The University of Texas.

Samuel, Jérôme. 2008. Kasus Ajaib Bahasa Indonesia? Pemordernan Kosakata dan Politik Peristilahan. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia (KPG).

Schiffman, H. F. 1997. “Diglossia as a Sociolinguistics Situation”, in Coulmas, Florian. (Ed.).1997. The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. UK: Blackwell Publisher Ltd.

Scollon, Ron and Suzanne Wong Scollon. 2001. Intercultural Communication: A Discourse Approach. UK: Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Sneddon, J.N. 2003. “Diglossia in Indonesia”, source: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl

Smith-Hefner, Nancy. 1988. Women and politeness: The Javanese example.

Language in Society, Vol. 17, 535-554.

Sumarsono. 2002. “Alih Kode dan Silang Kode”, Dalam Ied Veda Sitepu (Ed.). 2002. Festschrift 70 Tahun Pak Maurits Simatupang. Jakarta: Universitas Kristen Indonesia Press.

Supardo, Susilo. 1999. Sistem Honorifik Bahasa Jawa Dialek Banyumas: Sebuah Kajian Sosiolinguistik. Yogyakarta: PPs. UGM. Disertasi. Tidak diterbitkan.

Taufiq, Abu. 1995. Kitab Tarjamah Al Quran Krama Jawi. Temanggung: CV. Hafara. Jilid I.

Wajdi, M. 2009a. “Verba Derivasi Bahasa Jawa: Kajian Morfologi dan Sosio-kultural”, Makalah disajikan pada Seminar Nasional Bahasa Ibu 2, Program S2/S3 Linguistik UNUD, Denpasar, 27—28 Februari 2009.

Wajdi, M. 2009b. “Alih Kode dan Silang Kode: Strategi Komunikasi dalam Bahasa Jawa”, Dalam Sukyadi, Didi (Ed.). 2009. Proceeding of the 2nd International Conference on

Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2), UPI Bandung, 3—4 Augustus 2009. Bandung: CV Andira and UPI Press.

Wajdi, M. 2010a. “Politeness Systems in Javanese”, Makalah pada Seminar Nasional Bahasa Ibu III, Program S2/S3 Linguistik UNUD, Denpasar, 25—26 Februari 2010. Denpasar: Udayana University Press.

Wajdi, M. 2010b. “Code-crossing: Hierarchical Politeness in Javanese”, Proceeding of International Seminar on Austronesia Languages. Denpasar: Udayana University Press.

Wajdi, M. 2011a. “Ketidak-setaraan dan Pola Komunikasi Masyarakat Tutur Jawa”, Makalah Seminar Nasional Bahasa Ibu IV, diselengarakan oleh Program Studi S2/S3 Linguistik UNUD, Denpasar, 25—26 Februari 2011.

Wajdi, M. 2011b. “Code-choice and Politeness in Javanese”, Paper presented at The Third International Symposium on the Language of Java (ISLOJ 3), held by Mac Plank Institute, UNIKA Atmajaya and UIN Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang, Malang 23— 24 June 2001.

Wajdi, M. 2011c. “Reinterpretasi Teori (Sistem) Sapaan dari Brown and Gilman (1960): Analisis Penggunaan Tingkat Tutur Bahasa Jawa”, Makalah Konferensi Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia (KIMLI), UPI Bandung, 09—12 Oktober 2011.

Wajdi, M. 2012. “Sistem Kesantunan Masyarakat Tutur Jawa”, Dalam Linguistika Vol.

19, No. 36 Maret 2012. Denpasar: Program Studi Magister (S2) dan Doktor (S3) Linguistik Universitas Udayana bekerjasama dengan Asosiasi Peneliti Bahasa-bahasa Lokal (APBL).

Wijana, D. P. 2008. “Kata-Kata Kasar dalam Bahasa Jawa”. Yogyakarta:Humaniora Vol. 20 nomor 3, Oktober 2008.

Wolff, J.U. and Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo. 2002. Communicative Codes in Central Java. New York: Southeast Asia Program Publication.

16

Discussion and feedback