Language Diversity in Japan

on

e-Journal of Linguistics

Available online at https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eol/index

Vol. 18, No. 1, January 2024, pages: 127--134

Print ISSN: 2541-5514 Online ISSN: 2442-7586

https://doi.org/10.24843/e-jl.2024.v18.i01.p12

Language Diversity in Japan

1 Ni Putu Luhur Wedayanti

Udayana University, Denpasar, Indonesia Email : luhur_wedayanti@unud.ac.id

Article info

Received Date: 8 September 2023

Accepted Date: 25 September 2023

Published Date: 31 January 2024

Keywords:*

Japanese language, language diversity, sign language

Abstract*

As the world becomes more borderless, it is hard to find any country that remains homogeneous. Japan, which is well-known as a homogeneous and monolingual country, also has diversity in their language phenomenon. This study uses a qualitative research approach, because the direction of this research is to examine language phenomena that occur in Japanese society as the subject and source of this research. Even within Japanese people there is sign language that is used by the Japanese Deaf or hearing people who sign fluently. The Japanese sign language (nihon shuwa) has its own system different from the Japanese language. The presence and increasing recognition of sign language has created awareness of heterogeneity and diversity in culture in Japan.

Japanese society is often referred to as a homogeneous society because it consists of only one type of ethnic group and uses only one language. However, in recent years, the proportion has gradually disappeared along with the emergence of diversity in various forms within the society. It is not only the emergence of people with different skin colors that are increasingly spreading to almost remote corners of the country but also a variety of culinary culture, fashion, or street signs in public spaces that have entered Japan and made its people being more accustomed to multilingualism. In big cities in the country, there are quite a number of foreigners and even shops or business ventures of the diaspora who have managed to find a decent living and have lived for generations in the country (Wedayanti & Dewi, 2022). These phenomena make Japan’s belief as a monolingual country as well as a country with a single ethnic group increasingly disappeared. In addition, there are also studies which found that the Ainu tribe in Japan and the people of Okinawa or the languages of the Ryukyu Islands have a language system that is distinguishable from Japanese. The language could not develop and even now almost becomes extinct because during the Meiji era, it was strictly prohibited from being used by the Meiji Government at that time. At that time the Meiji government also considered that centralized uniformity would make Japan better and easier to govern (Bukh, 2010; Burgess, 2005; Godefroy, 2012; Wedayanti & Dewi, 2021).

The diversity of language modalities in Japan is signified by the existence of the language used by deaf people, that is sign language. Sign language is believed to be a language that

appeared along with the emergence of deaf people on this earth (Fisher, 2014). The deaf use their hands to produce speech so that, often their speech organs are not trained to speak. Therefore, in general, people who are deaf from birth tend to be deaf and mute. Even though these people are deaf and mute, they can still communicate using sign language both with other deaf people and with hearing people who able to communicate using sign language. In Japan, sign language has been developing for a long time, even before the Japanese occupation in Korea (Hara, 2002; Nakamura, 2006). South Korean Sign Language (SKSL) and Taiwan Sign Language (TSL) are referred to as the Japanese Sign Language Family based on the language contact that took place during the Japanese occupation of the two countries, precisely before the second world war (Matsuoka et al., 2023). This paper describes the existing and developing sign language as a modality form distinct from the spoken language used in Japan. In the literature review section, some of the results of past studies conducted on Japanese sign language are used and in the discussion section the general characteristics of Japanese language and Japanese sign language are presented as a comparison of variations in the modality of language in the country.

Hara (2002) states in her article entitled “Japanese Sign Language: An Introduction” that JSL has actually been used in Japan for quite a long time. It is just that, because there is no written evidence it is very difficult to determine or trace the initial linguistic traces of sign language in the country. Historically, JSL first appeared when a school for the blind and deaf opened in Kyoto (Kyoto Moain or The Kyoto School for the Blind and Deaf). Interaction between deaf students from various regions studying at the school formed a pidgin which gradually became a creole, and after undergoing a grammaticalization process, JSL started to be recognized as a language. This situation is precisely similar to that of the emergence of the Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL) which emerged after a school for the deaf was opened in the country (Hara, 2002).

Torigoe found that gestures have different modalities compared to spoken language as language with aural-oral, that is to say, the visual gestural mode of communication. The word in sign language is referred to as a sign which carries three important forming components, such as the shape of the hand, the movement of the hand, and the position or location of the hand that gives the signal. These three components are the basic parameters of phonological studies which greatly influence the morphological system in sign language. Furthermore, Torigoe described the early period of child development in acquiring Japanese sign language (hereinafter referred to as JSL) in the country. Just as the acquisition of spoken language is concerned with the environment and language input, Torigoe conducted several further studies to examine the interactions between their mothers and their deaf children in everyday communication situations. Although with different modes, deaf mothers also used several child-directed utterance (CDU) or motherese patterns in interacting with their children. For example, the mother wanted to enter the child’s signaling spatial area to get their attention, which she would not do when communicating using signs with other adults. In the process of perfecting language mastery using signs, deaf children also experienced phonological errors. Of the 96 sign errors found in the spontaneous communication of deaf children, Torigoe found that error of movement was the main error, then in the next stage the errors in the shapes of hands in gesturing increased. Meanwhile, there was a

129 slight misplacement of the hands. For instance, the sign for TO EAT (in JSL) was indicated by straightening the index finger and middle finger. However, errors in the shapes of the hands also occurred in children who frequently only signaled their parents with a straightened index finger (Torigoe, 2016). Still regarding children sign language, Torigoe & Takei (Torigoe, 2016) compared the pointing habits of deaf children and those of children who could hear. The results showed that there were two patterns of errors in the use of signs which were two combinations of gestures and consisted of one gesture and one pointing gesture. Torigoe’s research comprehensively examined Japanese sign language and the acquisition and use of Japanese sign language by children.

This study uses a qualitative research approach, because the direction of this research is to examine phenomena that occur in society as the subject and source of the research. Qualitative research departs from empirical phenomena that occur in society which is then followed by proving concepts or social scientific principles to generate a conclusion. This study examines linguistic phenomena that occur in Japan by paying attention to the concepts of homogeneity and heterogeneity as well as the general characteristics possessed by Japanese language and Japanese sign language itself. Within an explicit scope, this study seeks to formulate conclusions that remain within the boundaries of the topic, which is the diversity of language facilities and perceptions, or the diversity of language modalities that exist in Japanese society.

Japanese is the official language used by Japanese people in various official and casual activities in their everyday lives. Japanese belongs to the Altaic language family and is characterized as an agglutinative language (Igarashi, 2003). Aspects, modalities, and tenses in Japanese are very productive, integrated morphologically into a word, and thus many words in Japanese are classified as polymorphemic. As a vocal language, Japanese letters always end in an open vowel and form syllables for consonants ending with each of the five vowels a, i, u, e, o. For instance, the consonant /k/ will have a series of syllables ka, ki, ku, ke, and ko. Combination of several syllables forms a word, such as kaku ‘to write’; kiku ‘to listen’; and kaki ‘persimmon’. Orthographically, Japanese also recognizes four types of letters, namely Hiragana, Katakana, Kanji and Romaji. Each of these writings has its own form and function.

Letters of Hiragana have a more rounded shape and are used to write vocabulary that is classified as native Japanese vocabulary. Letters of Katakana have a more angular shape and are usually used to write vocabulary that is not native Japanese, or borrowed Japanese. Kanji is a form of writing brought home by Japanese scholars who were sent to study in China in the fifth century. At that time, Kanji letters could only be used by men, because at that time only men in Japan were allowed to receive education, so only men could write and read kanji. Nowadays, there is no longer any discrimination in the use of Kanji, and in general Kanji is used to write official documents. Romaji letters or letters of the alphabet are used to write foreign vocabulary that cannot be written using the other three types of letters. In general, Japanese has a

grammatical structure with a SOV pattern, which is followed by a postpositional particle which contains information regarding topicalization, tool, causality, obligue and others. As previously mentioned, Japanese is an agglutinative language, whose morphological processes are said to be very productive. The following is an example of a sentence that shows the agglutinative character of Japanese sentences and a highly productive morphological process.

-

(1) Okusama-ga otaku-ni irassya- imas- u- ka.(Igarashi, 2003) wife-subject home-at be(humbly)-non-familiar-non-past-question ‘Is your wife home?’

-

(2) Harasumento is composed with the word buraddo ‘blood’ (Wedayanti, 2015)

buraddo +harasumento blood harassment;

discrimination

→buraddo harasumento → burahara

‘harassment (discrimination) because of blood group differences’

The two example sentences show that in one word irassyaimasu ka, there is a lot of information contained as aspects and modalities in it. Then, there is the word burahara ‘discrimination because one has a different blood type than most of the blood groups that members have in their community’. Burahara is derived from an absorbed word which then undergoes a process of clipping on the first two syllables in each word.

Sign language in Japanese is known as nihon shuwa. The word shuwa is formed from two kanji words: shu ‘hand’ and wa ‘to speak; to say’; thus, the word can be interpreted as a word which means ‘to speak with the hand’. The proportion corresponds to the way in which deaf people produce speech, that is to say, using their hands to communicate. Sign language is the language used by deaf people, people who cannot hear or people who have lost their hearing at birth or at a later stage in that person’s life. Because they cannot hear, deaf people usually rely on their visual capability to perceive things in their daily lives and then produce speech to communicate using their hands.

There are two systems of sign language used in Japan, which are sign language which emerged and developed in the deaf community and is called nihon shuwa or Japanese Sign Language (JSL), and sign language which is a sign manifestation of spoken Japanese or nihongo taiou shuwa (The Sign System of Japanese Language). The signed spoken Japanese is used in the only school for the deaf at The Tochigi Perfectural School for Deaf. Tanokami Takashi is a teacher who implements dojiho, which is a similar system used in English to speak orally while gesturing in formal or spoken Japanese. This proportion makes the deaf generation attending the school use signs that are quite different from the ones used in other areas of Japan (Nakamura, 2006).

Japanese has an alphabetic (orthographic) system which includes not only the Arabic alphabet but also Hiragana, Katakana and Kanji letters. Variations in the shape of the letters are also found in Japanese sign language. In general, the finger signs (yubimoji) used are finger signs that

131 combine ASL, realistic descriptions that resemble letter shapes or those that use homophones with the syllables in the yubimoji, and use number and shape signs that are close to the Katakana letters. Kanji letters that are still simple are usually indicated by writing these letters in the area in front of the marker. For example, hito ‘person’ will be signaled by moving the index finger of the hand following the shape of the Kanji for hito ‘person’.

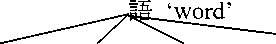

Hara gave an overview regarding JSL studies which can and deserves to be studied from the language rules themselves. JSL is a natural sign language that is very distinguishable from spoken Japanese. There are at least three important components that determine the meaning of a sign, such as hand shape, location of sign, and movement. These components are also said to be the smallest units of a sign, cannot stand alone and function or have meaning when joined with other components. These components will distinguish the minimum pair of each sign, like a segment of a phoneme that can be deconstructed to get the smallest phoneme unit. For example, the Japanese for WAKAI ‘young’ and KOUKOU ‘high school’ are minimal pairs because they are both located on the forehead (temple); the movement of the same sign is away from the body of the signaler but has a different hand shape. The following is an illustration of this explanation.

Fig. 1. left of wakai ‘young’; right of koukou ‘high school’(Hara, 2002)

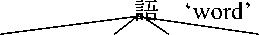

In terms of grammatical aspect, Japanese sign language is parallel to one word in Japanese language, consisting of at least three parameters, such as the shape of the hand when gesturing, the location of the hand when producing the sign and the direction of the gesture. These three components of parameter can form a complete and meaningful sign vocabulary unit. Likewise spoken language, sentences in sign language are composed of several simultaneous or sequential signs. The following is segmentation in the linguistics of sign language.

文 ‘sentence’

手形 手のひら向き 位置 動き 手形 手のひら向き 位置 動き

‘form ‘orientation ‘location’ ‘gesture ‘form ‘orientation ‘location’ ‘gesture

Chart 1. Segmentation in the linguistics of sign language (Matsuoka, 2015)

Sign language as previously mentioned is a language whose main input is visual and occurs both simultaneously and spontaneously, so the general word order in sentences is an object followed by a verb, as in the construction of the following sentences:

-

(3) a. chichi pan taberu (JSL)

father-S bread-O eat-V

‘Father eats bread’

-

b. chichi wa pan o taberu (Japanese language)

father-S TOP bread-O ME eat-V

‘Father eats bread’

In (3-a), (JSL) the sentence structure is not equipped with particles, distinct from spoken Japanese which requires the presence of certain particles to understand the meaning of the sentence as a whole. Although sign language does not have accusative markers, it still has patterns in distinguishing transitive and intransitive sentences. If there are two sentences that have both transitive and intransitive constructions, the verbs that appear will be in the same sign form. The strategy used is to use the actor’s pointing system at the end of the sentence (Matsuoka, 2015). Here is the explanation:

-

(4) a. /PT2 hon yaburu PT2/ (Matsuoka, 2015)

Pr2 book ruin Pr2

‘You ruined (your) book’

-

b. /PT2 hon yaburu PT3/ (Matsuoka, 2015)

Pr2 book ruin Pr3

‘Your book is broken’

In (4-b) the signaler points to the third person and explains that the actor is neither the first nor the second person, and the focus shown is the object of the book. Structurally, sign language uses several strategies to be able to convey the speaker’s intent within the scope of sentence construction.

The focus of this study is analysis of the existence of languages other than spoken language that are actively used in Japan. Japan, which most people know as a homogeneous and monolingual country, has turned into a multicultural and multilingual country. Although sign language is a minority language in terms of the percentage of users compared to spoken language, sign language is present in society at various moments involving the deaf in Japan.

This study departs from the fact that there is sign language as a modality of language use which is generally different from the spoken language used by the majority of Japanese people. Sign language is produced by hand as manual features and expressions and by mouth movements, eye gaze directions as non-manual features forming words, and sentences are composed by

133 several sign vocabularies simultaneously or sequentially. Japanese language, which has more than one type of writing, is also represented in Japanese sign language finger gestures. Finger signs (yubimoji) in Japanese sign language consist of syllables that have realistic references to their syllables, resembling katakana letters, homophones with number signs, as well as some finger signals borrowed from American sign language. The presence and increasing recognition of the various differences existing in Japan have solidified the position of Japanese sign language as a language study that has a language system and structure that is identical with the rules of spoken language.

References

Bukh, A. (2010). Ainu identity and Japan’s identity: The struggle for subjectivity. Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, 28(2), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.22439/cjas.v28i2.3428

Burgess, C. (2005). Jepang yang multikultur? Wacana dan mitos homogenitas [1] Chris Burgess Translated by Dipo Siahaan with the assistance of Susy Nataliwati, Muhamamad Surya and Danarto Suryo Yudo.

Fisher, S. D. (2014). Sign languages in their historical context. The Routledge Handbook of

Historical Linguistics, August 2014, 442–465. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315794013.ch20 Godefroy, N. (2012). The Road from Ainu Barbarian to Japanese Primitive: A Brief Summary of Japanese-Ainu Relations from Edo to Meiji. Consortium Making a Difference -Representing/Constructing the Other in Asian and African Media, Cinema and Languages: Consortium of African and Asian Studies (CAAS), 1–10.

Hara, D. (2002). 17 Japanese Sign Language: An introduction.

Igarashi, Y. (2003). Japanese As An Altaic Language: An Investigation of Japanese Genetic Affilliation Through Biological Findings. Proceedings of the 19th Northwest Linguistics Conference, 17, 35–47.

Matsuoka, K. (2015). Nihonshuwa de Manabu SHuwa Gengogaku no Kiso (Foundations of Sign Language Linguistics with a Special Reference to Japanese Sign Linguistics). Kuroshio Publisher.

Matsuoka, K., Crasborn, O., & Coppola, M. (2023). East Asian Sign Linguistics (M. Coppola, O. Crasborn, U. Zehshan, & S. M. Michaelis (eds.)). De Gruyter Mouton.

Nakamura, K. (2006). The Politics of Japanese Sign Language. In Deaf in Japan: Signing and The Politcs od Identity (pp. 13–30). Cornell UP.

Torigoe, T. (2016). Japanese Sign Language. In Handbook of Japanese Applied Lingustics (Vol.

-

21, Issue 0, pp. 137–143). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.7877/jasl.21.81 Wedayanti, N. P. L. (2015). Produktivitas kata Harassment Berkomposisi Dalam Bahasa Jepang.

PRASI: Jurnal Bahasa, Seni, Dan Pengajarannya, 10(19), 36–44.

https://ejournal.undiksha.ac.id/index.php/PRASI/article/view/8853

Wedayanti, N. P. L., & Dewi, N. M. A. A. (2022). Mobilitas Sosial Pada Kelompok Zainichi Korean di Jepang. Jurnal Sakura, 4(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/DOI: http://doi.org/10.24843/JS.2022.v04.i01.p03

Wedayanti, N. P. L., & Dewi, N. M. A. A. (2021). Wacana Rasisme Terhadap Golongan Minoritas di Jepang (Tinjauan Analisis Wacana Kritis). International Seminar On Austronesian Languages And Literature, 9(1), 201–205.

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/isall/article/view/79907

Biography of Author

Ni Putu Luhur Wedayanti is a lecturer in the Japanese Department, Faculty of Humanities, Udayana University. She is currently completing his dissertation at Udayana University. She has broad interest in researching correlation between language and culture.

Email: luhur_wedayanti@unud.ac.id

Discussion and feedback