RATIONAL MANAGEMENT OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE

on

RATIONAL MANAGEMENT OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Mun Yin Yen1, Ketut Tirtayasa2, Dewa Putu Sutjana2

-

1Medical Student of Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University

2

-

2Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University

ABSTRACT

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disease which is characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms. The motor symptoms which are also known as cardinal features are resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability. The etiology is unknown in most cases but there are findings that relate Parkinson’s disease to the genetics and environmental factors. The clinical course of Parkinson’s disease varies from patient to patient. Levodopa is still the main therapy of this disease although it leads to motor complications as the disease progresses.

Keywords: Parkinson, bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, postural instability, Levodopa

Introduction

One of the most common neurodegerative disorders of the central nervous system is

Parkinson’s disease. It belongs to a group of conditions called movement disorders or motor system disorders. 1 In general, Parkinson’s disease usually affects people above the age of 50. It has been associated with a heavy burden of the illness itself and cost to the society, thus it is important for the society to know about it.2,3,4

Parkinson’s disease, also known as "primary parkinsonism" or "idiopathic

Parkinson’s disease" has no known cause. However, genetic mutation accounts for the cause in afew cases. "Secondary" cases of parkinsonism may result from toxicity.1,3 The pathophysiology of it is generally associated with a loss of dopamine to the brain which results from death of certain brain cells that secrete dopamine.1, 4

The four primary symptoms or cardinal features are muscle rigidity, tremor at rest, a slowing of physical movement which is called bradykinesia, and postural instability. Early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease often occur gradually. As the disease progresses, it will begin to interfere with patients’ daily activities. Symptoms may also progress faster in some people. The diagnosis is entirely based on medical history, neurological examination and clinical manifestations. 1,3,5

Parkinson's disease is a chronic disorder that requires a management plan that should include patient and family education, support group services, general wellness maintenance, physiotherapy, exercise, and nutrition. At present, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, but medications or surgery can provide relief from the symptoms. It is most commonly treated with drugs that replace the lost dopamine.6, 7

Epidemiology

Parkinson’s disease affects about 1 to 2% of individuals over the age of 50 and 1 to 2% of those over age 60 worldwide.4,8 According to Guttman et al, in Ontario, the annual crude prevalence of Parkinson’s disease from year 1993 to 1999 was 3.6 per 1000 population among men over the age of 25 and 3.2 per 1000 among women over the age of 25. Over 90% of patients were over 60. The society often thinks of Parkinson’s disease as an elderly disease. However, it can occur in any age group.1,3

Etiology

The cause is unknown for majority of patients with Parkinson’s disease. However, there are growing evidences that suggest Parkinson’s disease may be due to a combination of environmental and genetic factors. These factors cause degeneration of the nigrostriatal dopamine-producing neurons and loss of pigmented neurons in the substantia nigra which thus induce the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.1,3 The etiologies of Parkinson’s Disease are divided into genetic factor and environmental factor.

According to Guttman et al, 2 mutations in the alpha-synuclein gene (PARK 1) were found in a few Greek and Italian families that caused autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease. A wide variety of mutations of another gene which is called Parkin gene (PARK 2) have also been found in 50% of families in which at least one of the affected siblings developed symptoms at or before 45 years old.3 Therefore, it is likely that the symptoms of patients younger than the age of 50 are related to genetic factors, while the disease appearing after the age is caused by both genetic and environmental factors.1, 2

The environmental toxin here refers to the MPTP (pro-toxin N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine), a toxin that destroys dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra. Studies suggest that Parkinson's disease might be caused by environmental toxins when several drug addicts were discovered to develop symptoms of Parkinson's disease after injecting the synthetic narcotic. The symptoms were caused by a contaminant called MPTP which has a strong chemical similarity to many pesticides and other environmental chemicals.2,3 The toxins most strongly suspected are certain pesticides and transition-series metals such as manganese or iron. 8,9

Pathophysiology

Although the etiology of Parkinson's disease is not completely understood, the condition probably results from several factors. The first is an age-related death of the approximately 450,000 dopamine-producing neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra. For every decade of life there is estimated to be a 9% to 13% loss of these dopamine-producing neurons.10,11

The environment has already proposed etiologies for Parkinson's disease which are quite definitive after the discovery of the neurotoxin (MPTP). There are also a number of other environmental neurotoxins which have also been described to lead to parkinsonian state. Thus, Parkinson's disease may develop as a combined consequence of the ongoing aging process and environmental exposures that worsen the nigral cell death.11,12,13

Some individuals may have a predetermined genetic susceptibility to these environmental toxins.4,10 A number of families in Greece and Italy were shown to have a mutation on chromosome 4 for the alpha-synuclein gene which is one of the major components of the lewy bodies and member of proteins that are expressed within the substantia nigra. It is a presynaptic protein of unknown function. The mutation of this gene is associated with the autosomal dominant Parkinson's disease.2,3,4

Another gene abnormality on chromosome 6 has been found in patients with autosomal recessive form of young-onset Parkinson’s disease. The protein product of this gene, Parkin, is closely related to in several neurodegenerative disease.2,3,10 Parkin helps in

the degradation of certain neuronal proteins through the proteosomal degradation pathway. The loss of function of both parkin genes results in autosomal recessive form of youngonset Parkinson’s disease.3,4,10

Clinical Features

The cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease include tremor at rest, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. We can confidently diagnose that the patient has definite Parkinson’s disease if patient has any two of the four features above, with one of the two being tremor or bradykinesia. The presence of these cardinal features can be used to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other related Parkinsonian disorders. However, motor and non-motor impairments should be evaluated as well.1,3,5 The primary symptoms result from decreased stimulation of the motor cortex by the basal ganglia which is normally caused by the insufficient formation and action of dopamine. Secondary symptoms may include high level cognitive dysfunction and subtle language problems.1,3,5

Bradykinesia is usually the most characteristic symptom although it may be present in other disorders. Patients report slow movement and reactions times when performing their activities of daily living.1,5 Other manifestations of bradykinesia include loss of spontaneous movements and gesturing, drooling because of impaired swallowing, monotonic and hypophonic dysarthria, loss of facial expressions, reduced arm swing while walking. Watching a patient get up from a chair is helpful in assessing patients.5,14

Resting tremor is the most common and most easily recognized symptom, present in 70% to 80% of patients. It often starts in one extremity and worsens with precipitating factors such as stress, fatigue, and cold weather. It may be confused with the more common essential tremor, but can be differentiated if it occurs predominantly at rest or with action. Tremor in Parkinson’s disease normally occurs at rest while tremor occurs with action is essential tremor. Essential tremor tends to begin more symmetrically, whereas patients with Parkinson’s disease usually have a unilateral tremor.1,5

Rigidity is characterized by increase in tone or resistance, which is velocityindependent. Rigidity is usually accompanied by the “cogwheel” phenomenon on examination. For example, when a patient move passively, the patient’s limb may seem to

repeatedly catch and release. However, it must be distinguished from the rigidity resulting from upper motor neuron lesions. In Parkinson’s disease, passive movement of the joints reveals continuous resistance throughout the whole range of motion. In upper motor neuron lesions, the muscles suddenly relax after an initial period of rigidity to movement.1,3,5

Postural Instability or impaired balance is common in Parkinson’s disease, which is caused by the loss of postural reflexes and it is generally a feature of the late stages of Parkinson’s disease. It usually occurs after the onset of other clinical features. Postural instability may lead to fall-related injuries, restriction in gait patterns and decreased mobility. The pull test is used to assess the degree of retropulsion. When performing this test, patient is quickly pulled backward or forward by the shoulders to assess the degree of retropulsion or propulsion, respectively. A patient who takes more than two steps backwards or do not have any postural response indicates an abnormal postural response. 1,5

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Parkinson's disease is based on medical history, clinical criteria and a neurological examination of patients. The clinical criteria for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease are the cardinal features including tremor at rest, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability.3,5 We can diagnose that the patient has definite Parkinson’s disease if patient has any two of the four features above, with one of the two being tremor or bradykinesia. The neurological examination includes an evaluation of walking and coordination, and simple hand tasks. 3,5,11

Table 1 : National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease.5

|

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease (PD) | |

|

Group A features (characteristic of PD)

Group B features (suggestive of alternative diagnoses)

symptom onset

years

gaze) or slowing of vertical saccades

medications

parkinsonism and plausibly connected to the patient’s symptoms (such as suitably located

months) |

Criteria for definite PD

obtained at autopsy Criteria for probable PD

present and

symptom duration >3 years is necessary to meet this requirement) and

dopamine agonist has been documented Criteria for possible PD

present; at least one of these is tremor or bradykinesia and

symptoms have been present (3 years and none of the features in group B is present

or a dopamine agonist has been documented or the patient has not had an

|

The only definitive diagnostic method of Parkinson’s disease is actually by pathological confirmation of the hall-mark lewy body on autopsy, while in clinical practice, diagnosis is basically based on the presence of a combination of cardinal motor features.1,5 Diagnostic criteria have been developed by the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to improve the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (see Table 1). Research shows there are only 8.1% of patients who did not meet these diagnostic criteria at the final diagnosis.3,5

Rational Management

Rational management refers to a management plan which patient’s lifestyles, backgrounds, traditions, and individual characteristics should be taken into account. Individual characteristics here include the severity of disease, co-morbidities, age and

others. At present, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, but there is a variety of medications which provide reliefs from the symptoms, physical therapy and surgery.1,6,7

Medications.

Medications improve the patient’s quality of life by helping in managing problems with walking, movement and tremor by increasing the brain's supply of dopamine. Medication varies for different stages of Parkinson’s disease. Medications which are used currently include levodopa, dopaminergic agonists, monoamine oxidase B (MAO B) inhibitors and antivirals.1,6

Levodopa is still the mainstay of therapy and the most effective Parkinson’s disease drug. It can improve all motor symptoms in early disease. Levodopa is a natural substance that we all have in our body, when taken orally in pill form, it passes into the brain and is converted to dopamine. Motor complications including motor fluctuations and dyskinesia can occur as the disease progress, because there is a decreased capacity for cells to take up Levodopa and store dopamine for continuous release in patients who are losing more and more dopaminergic cells. The onset of Parkinson’s disease at a younger age is related with earlier motor fluctuations which are more severe.1,7,15 Thus, it is important when selecting initial medications. A levodopa-sparing strategy may delay the onset of motor complications, for example, starting with a dopaminergic agent with longer half-life. There are a few drugs that can be used as part of this strategy, for example, amantadine, MAO B inhibitors, and dopinergic agonists. Levodopa’s side effects include confusion, delusions and hallucinations, as well as involuntary movements called dyskinesia.6,15

Dopaminergic agonists which includes ropinirole and pramipezole are effective in treating the motor symptoms when used as initial monotherapy. They may also help in delaying the onset of motor complications. Unlike levodopa, these drugs are not changed into dopamine. Instead, they mimic the effects of dopamine in the brain and cause neurons to react as if dopamine is present.1,15,16 However, they are not as effective in treating the symptoms of Parkinson's disease. This class includes pill forms, pramipexole (Mirapex) and ropinirole (Requip), as well as patch forms, rotigotine (Neupro).1,16 Bromocriptine (Parlodel) and pergolide (Permax) which are ergot-derived dopaminergic agonists are less

used because they are associated with pulmonary and retroperitoneal fibrosis and heart valve damage. Early use of dopaminergic agonists may reduce or delay the motor complications.1,15 The side effects of dopamine agonists include those of carbidopa-levodopa, but they are less likely to cause involuntary movements. They can also cause hallucinations, sleepiness, swelling, and increase the risk of compulsive behaviors.15,16

MAO-B inhibitors including selegiline (Eldepryl) and rasagiline (Azilect) which are effective as initial monotherapy can help to prevent the breakdown of both naturally occurring dopamine and dopamine formed from levodopa. They act by inhibiting the activity of the enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO B) which is the enzyme that metabolizes dopamine in the brain.1,16 MAO B inhibitors are effective as monotherapy in early disease and as adjuvant therapy in more advanced disease, but not as efficient as levodopa or dopamine agonists.6 Selegiline (Eldepryl) is metabolized to an amphetamine in the body and thus should be used carefully in the elderly patients or in patients prone to anxiety, cognitive difficulties or insomnia. Side effects of MAO B inhibitors are rare but can include serious interactions with other medications.1,6,16

Amantadine (Symmetrel) is an antiviral agent and N-methyl-D-aspertate glutamate receptor antagonist which provide short-term relief of mild, early-stage Parkinson’s disease when used alone initially. It may also be added to carbidopa-levodopa therapy for people in the later stages of Parkinson's disease, especially if they have problems with involuntary movements (dyskinesia) induced by carbidopa-levodopa. Side effects include swollen ankles and a purple mottling of the skin.1,15

Physical Therapy

Exercise is important for general health, but especially for maintaining function in Parkinson's disease. Physical therapy may be advisable and can help improve mobility, range of motion and muscle tone. Although specific exercises can't stop the progress of the disease, improving muscle strength can help patients to feel more confident and capable. A physical therapist can also work with patient to improve patients’ gait and balance. A speech therapist or speech pathologist can improve problems with speaking and swallowing.1

Surgery

Deep brain stimulation is the most common surgical procedure to treat Parkinson's disease. It involves implanting an electrode deep within the parts of your brain that control movement. The amount of stimulation delivered by the electrode is controlled by a pacemaker-like device placed under the skin in upper chest. A wire that travels under the skin connects the device to the electrode.1,6 Deep brain stimulation is most often used for patients with advanced Parkinson's disease who have unstable medication (levodopa) responses. It can stabilize medication fluctuations and reduce or eliminate involuntary movements (dyskinesias). Tremor is especially responsive to this therapy. However, the surgery may cause brain hemorrhage or stroke-like problems and infections. Deep brain stimulation isn't beneficial for people who don't respond to carbidopa-levodopa.1,6,16

Decision Pathway in managing a Parkinson’s disease patient

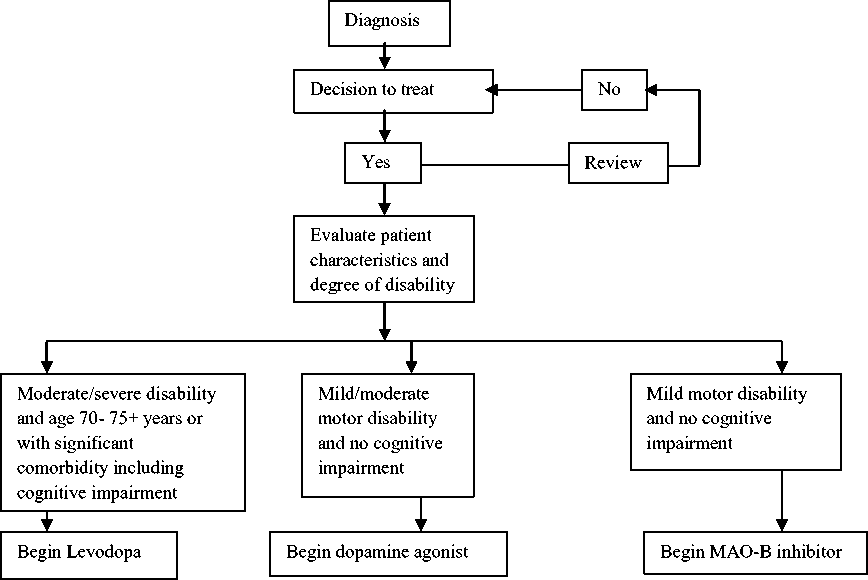

According to the figure below by Anthony et al, after the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and decision of patients to be treated, evaluation should be done on patient’s individual characteristics and degree of disability (see figure 1). Levodopa should be begun in patients with moderate or severe disability and age 70 to 75+ years or with significant co morbidity. But, if these patients are cognitively intact and lack any signifant co morbidity, MAO-B inhibitors or dopamine agonist can be initiated.

Patients who are below the age of 70 need a good symptom relief medication with minimum risk in adverse effects. For these patients with no cognitive dysfunction, the choices of medications are between MAO-B inhibitors and dopamine agonist.6,17 For patients with mild or moderate motor disability with no cognitive impairment, dopamine agonists should initially be given. Lastly, MAO-B inhibitor is used initially in patients with mild motor disability and no cognitive impairment. For patients who have cognitive dysfunction, levodopa treatment should be started and avoid dopamine agonists because dopamine agonists worsens the problem.3,6

Figure 1 : Decision pathway for the initiation of drug treatment for Parkinson’s disease 6

Medication given differs for different stages of Parkinson’s disease and should be given according to individual need especially the effects that Parkinson’s disease has on their working and home activity performances, life expectancy and quality of life. Besides, co morbidities, adverse effects and cost should also be taken into account.3,6

Levodopa is still the most efficient drug in reducing the signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and lower cost. Dopamine agonist is not as efficient as Levodopa in the reduction of signs and symptoms and higher cost and can only reduce but not eliminate the incidence of dyskinesia.1,6,17

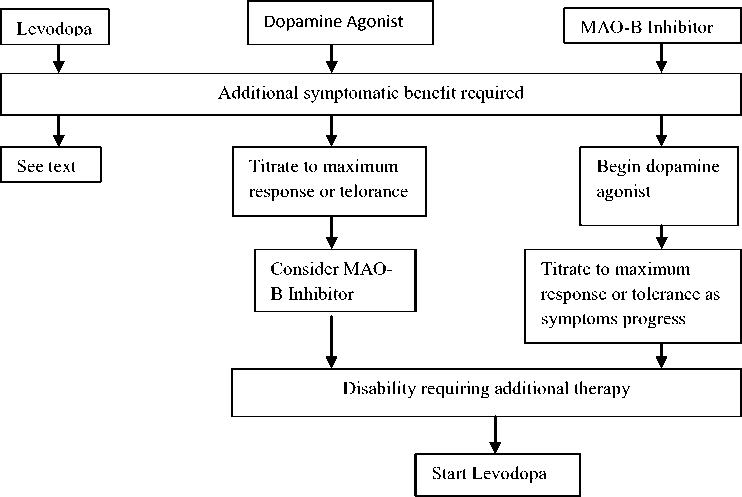

According to Anthony et al, patients who start receiving dopamine agonist or MAO-B inhibitor will still need levodopa at some point of time during the course of their disease.6 From the diagram below (see Figure 2), we can summarize that patients who have started with MAO-B inhibitor as an initial treatment, dopamine agonist should be given next. For those patients who are already receiving dopamine agonist with maximum

tolerance dose and who needs an additional treatment, MAO-B inhibitor should be given.

Levodopa is the subsequent choice for these patients.1,6,17

Figure 2 : Decision pathway for the sequence and combination of drugs in early

Parkinson’s disease. MAO-B indicates monoamine oxidase B.6

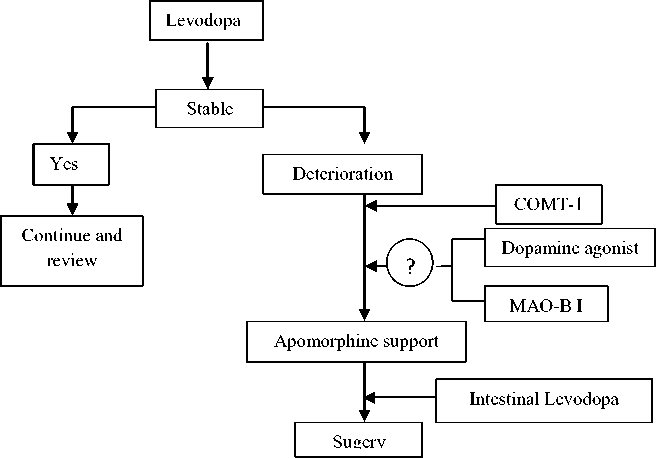

As for patients whom motor fluctuations have occurred and are already receiving levodopa, total daily dose of levodopa should be increased to control the symptoms better. Cathechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor should be added to help in the treatment of wearing off due to levodopa treatment. Total Levodopa dosage determines the motor complications. Thus, for patients who have already started receiving levodopa, addition of MAO-B inhibitor can improve control.6,17

Advanced patients are patients whose symptoms respond well to levodopa but who still suffer from significant tremor, end-of-dose wearing off, or dyskinesia should undergo deep brain stimulation. There are a few conditions that patients must fulfill to undergo this surgery including a secure diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, good respond to dopaminergic therapy, cognitively intact.1,6

Figure 3 : Decision pathway for the treatment of advancing and complex Parkinson’s disease. MAO-BI indicates monoamine oxidase B inhibitor; COMT-1, cathechol-o-methyltransferase inhibitor 6

Summary

The rational management of Parkinson’s disease includes medications, physical therapy, and surgery. There are a few medications available including levodopa, dopamine agonist, MAO B inhibitor, antiviral (amantadine). Levodopa is associated with motor complications but it is the most efficient medication in treating the symptoms among all. Dopamine agonist and MAO B are both helpful in reducing or delaying the onset of motor complications when used as initial therapy although they are not as efficient as levodopa. However, they can worsen the condition of cognitive impairment, thus cannot be used in patients who have cognitive dysfunction. Unlike levodopa which is converted into dopamine in the brain, dopamine agonist mimics the effect of dopamine while MAO B inhibitor prevents the breakdown of dopamine. Amantadine provides short-term relief of mild and early stage Parkinson’s disease and also helps in patients who are in the late stages who have dyskinesia. Physical therapy involves exercises, speech therapist in helping with speaking and swallowing problems. Surgery for Parkinson’s disease is deep brain

stimulation for patients who are still responding to levodopa and are cognitively intact, but has medication fluctuations and suffer from significant motor complications. It also helps in eliminating dyskinesia.

References

-

1. Giroux ML. Parkinson disease: Managing a complex, progressive disease at all stages. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2007;4(5):313-314.

-

2. Anthony H. Peter Jenner. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(6):1049-1055.

-

3. Guttman M, Stephen JK, Yoshiaki Furukawa. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168(3):293-301.

-

4. Thomas B, Beal MF. Parkinson’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16(2):183-194.

-

5. Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2007;79(4):368-376.

-

6. Anthony H. V. Schapira. Treatment Options in the Modern Management of Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(8):1083-1088.

-

7. Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2055–2066

-

8. Raimova M. Studtt of the role of environmental factors in development of Parkinson’s Disease. Medical and Health Science Journal. 2012;11:22-26\

-

9. Stein J, Schettler T, Rohrer B, Valenti M. Environmental factors in the development of Parkinson’s Disease. In: Myers N, editor. Enviromental Threats to Healthy

Aging. Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility and Science and Environmental Healthy Network. 2008, p.145-177.

-

10. Levy G. The Relationship of Parkinson Disease with Aging. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(9):1242-1246.

-

11. Weintraub D, Comella CL, Horn S. Parkinson’s Disease : Part 1 : Pathophysiology, Symptoms, Burden, Diagnosis, and Assessment. American Journal of Managed Care. 2008;14(2):S40-S48

-

12. Porras G. Qin Li. Bezard E. Modelling Parkinson’s Disease in Primates : The MPTP model. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2:1-10

-

13. Parkinson’s NSW. MPTP and drug-induced Parkinson’s. Parkinson’s NSW [online series] 2007 [accessed on 13 November 2012]. Downloaded at: URL: http://www.parkinsonsnsw.org.au/assets/attachments/documents/InfoSheet_1.7_MP TP%26Drug-InducedParkinson's.pdf

-

14. Zigmond MJ. Burke RE. Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editor. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2002;p.1781-1794.

-

15. Boll MC, Zubeldia MA, Rios C. Medical Management of Parkinson’s Disease: Focus on Neuroprotection. Current Neuropharmacology. 2011;9:350-359

-

16. Goldenberg MM. Medical Management of Parkinson’s Disease. P&T Community. 2008;33(10):590-606

-

17. Shobha S. Laura A. Hofmann. Amer Shakil. Parkinson’s Disease : Diagnosis and Treatment. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2006;74(12):2046-2054.

14

Discussion and feedback