WILDLIFE USE IN LAPUA COMMUNITY OF KAUREH, PAPUA

on

P ISSN: 1410-5292,

E ISSN: 2599-2856

JURNAL BIOLOGI UDAYANA 22 (2): 51 –58

WILDLIFE USE IN LAPUA COMMUNITY OF KAUREH, PAPUA

PEMANFAATAN HASIL BURUAN OLEH MASYARAKAT DI KAMPUNG LAPUA KAUREH, PAPUA

Wes Weyah, Henderina Josefina Keiluhu and Aditya Krisna Karim

Biology Department of Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Cenderawasih, Jayapura Papua *Corresponding author: henderinaj.keiluhu@gmail.com

Diterima 25 Juni 2016 Disetujui 21 Juli 2018

ABSTRACT

A wildlife study to find out about hunting wildlife was taken in Lapua Community, Kaureh, Papua. Specific purpose of the research was to obtain the information about wildlife species hunted, hunting techniques, and utilizations of hunted animals by the community. The study was taken place in September-October 2015, used survey method with interview techniques. The study found out about 19 species of wildlife as common hunted species, which could be grouped into 31.58% protected by Indonesian Law, 52.63 % usually used for self-consumption, and 68.42 % were birds. People in Lapua have their own traditional wisdom in hunting activities, which they know as active hunting which consists of eyehunting (Hwe), hunting with dogs (Seeht/kenang), skilled hunting (Mbree), and imitate animal sounds (Sukwe), while in passive hunting (Ptia) they use foot snares, confinement and bird nets. Hunting equipments for the community’s traditional hunting are spears (Tumuayuja), bows (Dyi) and arrow (Sii), rattan strings (Wii) and wood for mesh materials. The hunted animals are usually for self-consumption and to be raised up and for sale.

Key words: hunting, wildlife animals, traditional wisdom, Lapua Community, Papua

INTRODUCTION

Hunting wild animal becomes one inseparable activity from Papuan people’s life. This activity has been going since former times in order to fulfill people needs on food, economic commodities, medicines and culture accessories. For Papuan people, the utilization type of wildlife usually depends on the type of hunted animals and their own traditional knowledge on hunting. Hunted animals are generally preferred for consumption (Pangau and Noske, 2010, Iyai et al., 2011, Pangau-Adam et al., 2012 and Keiluhu, 2013), or being sold to meet the family’s economic needs (Pangau and Noske 2010, Pangau et al., 2012 and Keiluhu, 2013). The animals are also kept as a pet to be sold later when the hunter or owner needs money (Keiluhu, 2013). Hunted animals are valuable in cultural events because Papuan people use them as accessories (Kwapena 1984, Pattiselanno and Mentansan, 2010, Keiluhu, 2013).

Community of Lapua Village comprises of some indigenous tribes who live in the remote area in Jayapura Regency, Papua. This community mostly relies on shifting cultivation and poaching to fulfill their daily life’s needs. Similar to communities in many other areas in Papua, the information about people’s activities in utilize and consume wildlife resources is still insufficient. Hence, this study was carried out in order to obtain the information about wildlife species hunted, hunting techniques, and utilizations of hunted animals by the community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Time and Location

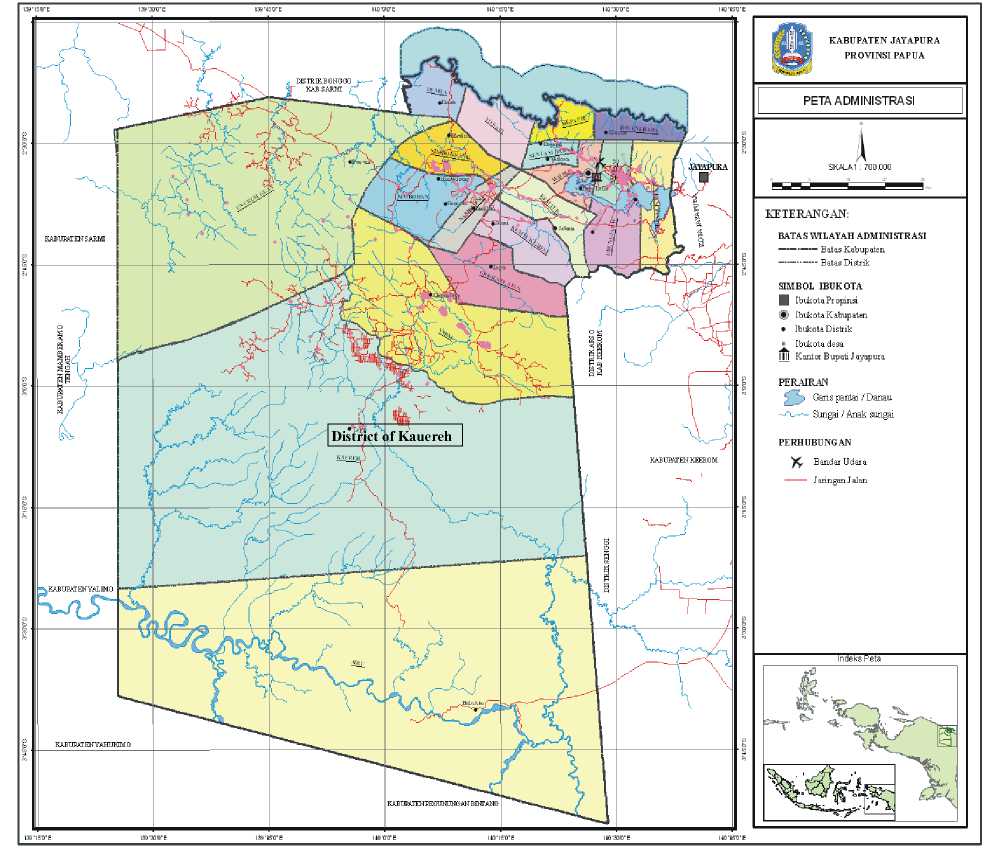

The research was conducted on September – October 2015 in the village of Lapua, Kaureh District, Jayapura Regency, Papua (Figure 1). The data were collected from some indigenous tribes within Lapua, which were Hirwa, Yamle, Masita, Bitaba, Auri, and Bogogo Tribe. These tribes then will be mentioned as indigenous tribes in this paper.

Research Materials, Data Collection and Analysis

Tally sheets were used as interview guide, with recorder, digital camera, and stationeries for documentation. The books of Mammals of New Guinea (Flannery, 1995) and Birds of New Guinea (Pratt and Beehler, 2015), also some wild animal photographs were used to assist ease the hunted animal identification.

Direct observations and open-ended interviews with prepared question list were taken for data collection. The list of research aspects and related data collected were adapted from Keiluhu (2013) and Novriyanti et al. (2014) (Table 1). The total of nineteen respondents for this study were determined 1) intentionally through purposive sampling, which consisted as tribal chief, village head and religious leader, and 2) randomly through random sampling, which targeted the hunter families. All data and information were then analyzed descriptively and described in tables and diagrams.

Figure 1. Research location

Table 1. Type of research data

|

No. |

Aspects |

Specific data recorded |

|

1. |

Utilization patterns |

|

|

2. |

Other values Beliefs, elderly or secret methods in hunting | |

RESULTS

Utilization Pattern of Hunted Animals

The total of 19 (nineteen) animals were hunted and utilized by the community of Lapua Village (Table 2). These hunted animals were mostly birds (13 species), and then followed by mammals (5 species) and reptiles

(1 species). Most of the animals were hunted for selling commodities, but some species were also hunted for domestic consumption, being raised as pets or preserved and set for accessories. Community of Lapua Village used mostly meat from the animals, then only few from other parts (skin, bones, fangs, claws, feather and horn), or they took the whole animal for sale or accessory. For consumption purposes, most of the meats were cooked, and then others were dried and roasted.

Table 2. Hunted wildlife of community in Lapua Village

|

No |

Species |

Tax a |

Purpose |

Body part needed |

Consumption methods | ||||

|

Local Name |

Scientific Name |

P |

C |

A |

S | ||||

|

1. |

Hysayah (Wild hogs – Babi hutan) |

Sus scrofa |

M |

v |

v |

v |

v |

meat, fang |

cook, dry, roast |

|

2. |

Kirinya (Deer - Rusa) |

Cervus timorensis |

M |

v |

v |

v |

v |

meat, horn |

cook, dry, roast |

|

3. |

Tinggano (Spotted Cuscus - Kuskus) |

Spilococus maculatus |

M |

v |

v |

v |

v |

meat, feather |

Cook |

|

4. |

Sauty (Bandicoot – Tikus tanah) |

Echimipera kalubu |

M |

v |

meat |

Cook | |||

|

5. |

Butuai (Fruit Bat - Kelelawar) |

Pteropodidae-u.i species |

M |

v |

v |

meat |

Cook | ||

|

6. |

Tarke (Monitor lizard - Biawak) |

Varanus sp |

R |

v |

v |

meat, skin |

Cook | ||

|

7. |

Kwii (Northern Cassowary - Kasuari) |

Casuarius unappendiculatus |

A |

v |

v |

v |

v |

meat, bone, feather |

cook, roast |

|

8. |

Mambruk (Victoria Crowned Pigeon) |

Goura victoria |

A |

v |

v |

v |

v |

meat, feather |

Cook |

|

9. |

Bahape (Megapod bird - Maleo) |

Megapodius freycinet |

A |

v |

v |

meat, feather |

Cook | ||

|

10. |

Yapung (Lesser Bird of Paradise -Cenderawasih) |

Paradisaea minor |

A |

v |

v | ||||

|

11. |

Yarini (Palm Cockatoo - Kakatua raja) |

Probosciger aterrimus |

A |

v |

v |

feather | |||

|

12. |

Yarini (Sulphur-crested Cockatoo – Kakatua jambul kuning) |

Cacatua galerita |

A |

v |

v | ||||

|

13. |

YariniSakrian (Black head Parakeet – Nuri kepala hitam) |

Chalcopsitta atra |

A |

v |

v | ||||

|

14. |

Yarini (Blue-Collared Parrot – Nuri kalung biru) |

Geoffroyus simplex |

A |

v | |||||

|

15. |

Yariniriykakriy (Moluccan Red Lorry – Nuri kalung ungu) |

Eos squamata |

A |

v |

v | ||||

|

16. |

YariniHimti(Electus Parrott – Nuri bayan) |

Electus roratus |

A |

v | |||||

|

17. |

Yatra (Spotted Whistling Duck- Belibis totol) |

Dendrocygna guttata |

A |

v |

meat |

Cook | |||

|

18. |

Yarini (RainbowLorikeet-Perkici pelangi) |

Trichoglossus heamatodus |

A |

v | |||||

|

19. |

Yarini(Western Black capped Lorry-Kasturi kepala hitam) |

Lorius lorry |

A |

v | |||||

Notes: ui: unidentification P: Preservation/Pet, C: Consumption, A: Accessories, S: Selling commodity, cook: cooked, dry: dried, roast: roasted

Conservation Status of Hunted Animals

Mostly hunted animals of community in Lapua Village are protected, some are positioned under Convension on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) status (Table

3). Many of them are already listed in International Union fot Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List, and also protected under the law of Republic Indonesia, while the rest are animals with uncertain status due to insufficient data.

Table 3. Conservation Status of Hunted Animals from Lapua Village

|

Species |

Status of Protection | ||||

|

No |

Local Name |

Scientific Name |

IUCN/Red List |

CITES |

PP No.2/1999 |

|

1. |

Hysayah (Wild hogs – Babi hutan) |

Sus scrofa | |||

|

2. |

Kirinya (Deer - Rusa) |

Cervus timorensis |

VU |

Yes | |

|

3. |

Tinggano (Spotted Cuscus - Kuskus) |

Spilococus maculatus |

VU |

II |

Yes |

|

4. |

Sauty (Bandicoot – Tikus tanah) |

Echimipera kalubu |

LC |

UC | |

|

5. |

Butuai (Fruit Bat - Kelelawar) |

Pteropodidae-u.i species | |||

|

6. |

Tarke (Monitor lizard - Biawak) |

Varanus sp | |||

|

7. |

Kwii (Northern Cassowary - Kasuari) |

Casuarius unappendiculatus |

VU |

UC |

Yes |

|

8. |

Mambruk (Victoria Crowned Pigeon) |

Goura victoria |

VU |

II |

Yes |

|

9. |

Bahape (Megapod bird - Maleo) |

Megapodius freycinet |

VU |

UC |

Yes |

|

10. |

Yapung (Lesser Bird of Paradise -Cenderawasih) |

Paradisaea minor |

LC |

II |

Yes |

|

11. |

Yarini (Palm Cockatoo - Kakatua raja) |

Probosciger aterrimus |

LC |

I |

Yes |

|

12. |

Yarini (Sulphur-crested Cockatoo – Kakatua jambul kuning) |

Cacatua galerita |

CR |

I |

Yes |

|

13. |

YariniSakrian (Black head Parakeet –Nuri kepala hitam) |

Chalcopsitta atra |

II | ||

|

14. |

Yarini (Blue-Collared Parrot – Nuri kalung biru) |

Geoffroyus simplex |

II | ||

|

15. |

Yariniriykakriy (Moluccan Red Lorry – Nuri kalung ungu) |

Eos squamata |

II | ||

|

16. |

YariniHimti(Electus Parrott – Nuri bayan) |

Electus roratus |

II |

Yes | |

|

17. |

Yatra (Spotted Whistling Duck- Belibis totol) |

Dendrocygna guttata | |||

|

18. |

Yarini (RainbowLorikeet-Perkici pelangi) |

Trichoglossus heamatodus |

II | ||

|

19. |

Yarini(Western Black capped Lorry- Kasturi kepala hitam) |

Lorius lorry |

II |

Yes | |

Notes : VU: Vulnerable, LC: Least Concern, UC: Unclear, I: Appendix I, II: Appendix II (Source: Research Data)

Hunting methods and tools

Community of Lapua village strongly follows the way of hunting inherited by their ancestors. They have five hunting methods which are commonly taken these days, though hunting using snare becomes the most common method (Table 4). Using dog to hunt is usually applied altogether with other hunting methods, because dog can sniff and chase targeted animals, so they can be easily caught or herded to the snare traps.

Types of hunted animals were various based on hunting methods. For instance, foot snares with smallsize nylon thread were used for small animals like ground-dweller pigeon, megapod bird and bandicoot,

while snares with big-size nylon thread or plastic rope were used for bigger animals such as hogs and deer. These animals were hunted at anytime, because hunters in Lapua community have no particular time preference for hunting activity.

Simple hunting tools were used by community of Lapua village during their hunting activity. They only used spears, dogs, foot-snares, and bird-nets, though modern tool like air gun was also recorded as one of the hunting tools in hunting (Table 5). Foot-snare as the most common hunting tool was used to catch cassowary, ground-dweller pigeon, megapod bird, bandicoot, wild hogs and deer. The community also has traditional names for the weapons, like Tumuayuja for spears, Dyif or bows, Sii for arrow, Wii for rattan strings and also use wood for mesh materials.

|

Table 4. Methods of hunting | ||||

|

No. |

Hunting technique (traditional name) |

Hunting methods |

Targeted animals |

Time of hunting |

|

1. |

Eye hunting (Hue) |

This hunting methoduse certain rules which are usually known only by the hunters and have to obey some taboos |

cuscus, bats, birds, monitor lizard |

night and day |

|

2. |

Hunting with dogs (Seeht/kenang) |

This hunting method use dog which can sniff, bark on the targeted animals, then startle and chase the animals |

wild hogs, deer, cuscus, bandicoot |

night and day |

|

3. |

Skilled hunting (Mbre) |

This hunting technique is only taken by particular hunter who knows the fruiting season in the forests, targeted animals’ playing and nesting sites |

cuscus, birds |

night and day |

|

4. |

Sound forgery (Sukwe) |

This hunting technique is taken by imitate the sound of certain animals, need more time and has rarely carried out specially by young people |

deer, cuscus, birds |

night and day |

|

5. |

Hunting with traps (Ptia) |

Most common and preferred hunting method |

wild hog, deer, cuscus, bandicoot, cassowary |

night and day |

Table 5. Hunting tools

|

No. |

Hunting tools |

Targeted animals |

Using method |

Notes |

|

1. |

Spears |

wild hog, deer, cassowary |

This weapon is thrown directly to the body of targeted animals |

Common |

|

2. |

Dog |

wild hog, deer, monitor lizard |

It sniffs and chases targeted animals |

Common |

|

3. |

Foot snare |

cassowary, ground-dweller |

It is set on the certain location around |

most |

|

pigeon, megapod birds, bandicoot |

sources of bird food |

common | ||

|

4. |

Bird net |

little birds |

It is set on the particular trees, which are |

most |

|

usually playing trees or forage trees |

common | |||

|

5. |

Air gun |

paradise bird, cuscus |

It is usually used around playing trees or forage trees of targeted animals |

rarely |

Taboos about hunting activity in Lapua community

People in Lapua community have one taboo related to hunting activity. Hunters from outside and from the community should keep away from Gunung Babi (Mount of Pig) area. The forest in this area is a sacred place for Yamle Tribe, one of indigenous tribes in Lapua village. This sacred place is named with Tapkay and Satae Tuy, means “prohibited to do any activity”. In addition to the taboo, there is a specific rule for the hunters or people from outside the community who want to hunt or gather forest products within the

Lapua’s community forest, they should report to and ask for the permission from village chief, local Ondoafi (tribe leaders) or any elders in Lapua.

DISCUSSIONS

Hunting becomes the main livelihood for local people in Papua and Papua New Guinea to fulfill the need of animal protein for their family, traditionally. People in Lapua community also sell their hunted animals to get fresh money beside consume the animals. The hunters use the money for their children’s education funds, house construction, and their other economic needs (Pangau et al., 2012; Keiluhu, 2013). The 54

meat from hunted animals that used for fulfilling the need of animal protein and partly for sale is named as bushmeat (Nasi et al., 2008; Pangau-Adam et al., 2012; Novriyanti et al., 2014). This kind of bushmeat has been known provide many ethnic groups needs of wildlife in the world at present (Novriyanti et al., 2014, Pangau et al., 2012).

Indigenous people in Papua prefer to sell their hunted animals for money than consume them. This is shown by the condition on Papuan indigenous people who live in Nimbokrang (Pangau and Noske, 2010), Mamberamo Catchment Area and Buare (Boissiere et al., 2004; Keiluhu, 2013), many parts in the Northern coast of Papua (South Supiori, Unurumguay, and Bonggo – Keiluhu, 2013), in Nabire (Pattiselano, 2007), and from this study in Lapua as well. This indicates that money becomes the main and inseparable part of the people’s life, though they live far from the city (Pangau and Noske, 2010; Keiluhu, 2013; Novriyanti et al., 2014).

Hunted animals are sometimes caught alive to be raised for pets and sold later. The young wild hogs, deer, cassowary and some parrots are usually caught alive to be raised as pets and sold later with higher price. Community in Lapua also use certain parts of hunted animals like hog tusks, antlers, fur-skin of possum and skin of monitor lizard as accessories in their culture events. For instance, wild hog’s tusk is used by people of Meyah Tribe in Manokwari (Fatem et al., 2014), while skins of deer, cuscus and monitor lizard are common accessories for Yaur tribe in Nabire (Iyai et al., 2011). It is also known that Cenderawasih (Paradise bird) has become the most hunted bird in Papua, which is usually used as souvenir, though it has zero quotas for trading and is already under protection of Peraturan Pemerintah (Government Law) No. 7/1999.

Various types of utilization on hunted animals and bushmeat are encountered in some areas in Indonesia and other places in the world as well. Rimba people (Forest people) in Jambi, Indonesia, usually hunt and use wildlife for source of meat protein and traditional medicines (Novriyanti et al., 2014). In other countries, there is a record about a group of indigenous people in Northeast India who use their hunted animals as source of protein and fresh money, and also for ornaments (i.e skull of wild hog and other animals, fantail of pheasant bird – Aiyadurai, 2011). Similarly, communities of Ngunnchang and Obang in Cameroon use horns, bones, skins, skull, even bile of hunted animals for traditional medicines, music equipments and decorations, beside for bushmeat and cash money source (Bobo et al., 2014).

Hunting activity may become very important for livelihood of local community around the forest, but it can be considered as a serious threat to the survival of wildlife, in Papua and also in the world as well. The rich rain forest area in Papua (Pattiselano, 2006 and 2008; Pangau and Noske, 2010; Pangau-Adam et al., 2012;

Keiluhu, 2013, Fatem et al., 2014), or in other area of Indonesia such as Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Sumatra (O’Brien and Kinnaird, 1996 and 2000; O’Brien et al., 1998; Novriyanti et al., 2014), and in foreign countries like Kameroon , Brazil and India ( Bobo et al., 2014; Barboza et al., 2016; Randrianandrianina et al., 2012; Aiyadurai, 2011; Aiyadurai et al., 2010) provides so many sources of food for local communities who live in the forest edges. This serious threat can be described by conservation status of hunted animals. Specifically in this study, some most-common hunted birds are already threatened; even the species of Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo has already get status of Critically Endangered on IUCN Red List (2012). Other species like cassowary, grounddweller pigeon, megapod bird and cuscus have already classified as Vulnerable. Many times, the preference of particular animal such as bird groups that can be sold as ornaments beside as food and money source might increase the threat to the group as the hunting target (Barboza et al., 2016, Pangau and Noske 2010, Mack and West 2005, O’Brien et al., 1998).

Hunting activities in Lapua community were mostly carried out with simple tools like foot snares, which are still used to catch small animals such as birds. The snare is commonly used by traditional hunters in Papua (Fatem et al., 2014, Pangau and Noske 2010, Pangau-Adam et al., 2012) and in other places, though other weapons like bows and arrows, or air gun are already used and show negative impacts to wildlife existence (Kwapena, 1984, Kumpel et al., 2008, Keiluhu, 2013).

In general, indigenous people in Papua still obey the traditional wisdom, knowledge and rules about taboo, sacred place and other rituals from their ancestors, especially indigenous people around remote forest (Wadley and Colfer, 2004; Pattiselano, 2006 and 2008). Community in Lapua can never enter or do any activities in their sacred area of Gunung Babi, the place where they believe as their ancestors’ dwelt. Similarly, many indigenous Papuans who live in Mamberamo Catchment Area really appreciate their forest and set prohibition or at least need particular ceremonies to enter it due to their traditional wisdom about forest as sacred place and home for their ancestors (Sheil et al., 2004). People from outside usually can never enter that area. Local people who want to go hunt need permission from tribe leaders and they also should obey other rules about hunting. It is believed that if the rules are violated, the hunters will get nothing during hunting, or might suffer from accident, illness and even death (Keiluhu, 2013).

Implication of Conservation

For Papuan, forest is usually considered as a mother who provides all the needs for the people, but the tremendous pressures on forest areas for development purposes, such as infra- structures development, road constructions and forest clearing for other purposes, as well as poaching and illegal trade are very difficult to be halt. The pressures already taken place and threaten to the existence of wildlife in their habitat. Hunting activity itself also cannot be banned because it has become part of the lives of the people of Papua since former

time. Additionally, tribes in Papua are different between one tribe to anotherin the aspects of ecological, social and institutional (Mansoben, 2005). Consequently, conservation approaches should pay attention to the traditional customs and habits of each ethnic group (Keiluhu, 2013; Pattiselano and Arobaya 2013).

It is commonly said that Papuans have already known rules and management system in using their forest and marine products, which are usually accompanied by such a customary punishments or sanctions for the violators (Mansoben, 2005; Makabori, 2005). The approach in the form of CBNRM (Community-Based Nature Reserve Management) has also been developed by PtPPMA (Limited Association for Assessment and Empowerment of Indigenous People) in several areas around Jayapura (Wamebu, 2000). Conservation International worked together with CIFOR to support the involvement of local people in manage and review their own natural resources (Boissiere et al., 2004; Padmanaba et al., 2012) using MLA (Multidisciplinary Landscape Assessment) to identify all important natural resources for local communities within the forest landscape. Some similar methods were also developed by WWF Papua Region to manage natural resource in the Wasur National Park Merauke (Supriatna, 2008). The main focus of CBRNM and MLA systems in Papua is to support local people in each village to participate in mapping and then reviewing their own natural resources. By doing these, local people can be able to record all of their hunting areas, sago-palm farms, villages, sacred places, and customary lands, also any taboos within their community (Boissiere et al., 2004; Padmanaba et al., 2012; Keiluhu, 2013 ).

Basically, it is shown that Papua and West Papua need local regulation such as Peraturan Daerah Khusus (Perdasus or Specific Regional Regulation) to control and to protect Papuan unique, endemism and valuable wildlife. Unfortunately, even though Special Autonomy in the local government has prevailed for a long time, there had been a lack of awareness and products of regulations to protect and conserve endemic wildlife specifically from illegal hunting and trade. Other important thing to do is enforcement of sanctions and punishments to the offenders in regard with the appropriate law, because it has not been implemented properly until now. A latest and better-distinct step that has been taken by Governor of Papua is to rule out all forms of hunting and the use of Bird of Paradise as well as a souvenir headdress (Loen, 2016). Then, the real action to put the ban on the Perdasus should be implemented immediately, to support conservation of Paradise birds and other wildlife as unique and endemic species in Papua.

CONCLUSIONS

Local community in Lapua Village utilize as many as 19 wild animals from hunting, consists of birds (68.42 %), mammals (26.32 %) and reptiles (5.26 %). The community use the

hunted animals as pets/preservation (63.16 %), consumption (52.63 %), accessories (36.84 %) and commodity for selling (84.21%). They use the dome different parts of animals’ body, namely fur, feather, flesh, skin, bones, also horns, claws and fangs.

This local community recognizes five hunting techniques in active hunting which are eye-hunting (Hwe), hunting with dogs (Seeht/kenang), skilled hunting (Mbree) and imitate animal sounds (Sukwe), while in passive hunting they use foot snares, confinement and bird nets.

REFERENCES

Aiyadurai, A., N.J. Singh, E.J. Milner-Gulland. 2010. Wildlife hunting by indigenous tribes: a case study from Arunachal Pradesh, North-east India. Oryx 44 (4): 564-572.

Aiyadurai, A. 2011. Wildlife hunting and conservation in northeast India: a need for an interdisciplinary understanding. Intl. J. of Galliformes Conservation 2: 61-73.

Barboza, R.R.D., S.F. Lopes, W.M.S. Souto, H. Fernandes-Ferreira, R.R.R. Alves. 2016. The role of game mammals as bushmeat in the Caatinga, Northast Brazil. Ecology and Society 21 (2): 2.

Bobo, K.S., F.F.M. Aghomo, B.C. Ntumwel. 2014. Wildlife use and the role taboos in the conservation of wildlife around the Nkwende Hills Forest Reserve South-West Camerron. J. on Ethnobiology and Etnomedicine 11 (2):1-23.

Boissiére, M., M. van Heist, D. Sheil, I. Basuki, S. Frazier, U. Ginting, M. Wan, B. Hariadi, H. Hariyadi, H.D. Kristianto, J. Bemey, R. Haruway, E.R.Ch. Marien, D.P.H. Koibur, Y. Watopa, I. Rachman, N. Liswanti. 2004. Pentingnya sumberdaya alam bagi masyarakat lokal di daerah aliran sungai Mamberamo, Papua dan implikasinya bagi konservasi. J.of Tropical Ethnobiology 1 (2):76-95.

Fatem, S., M.H. Peday, R.N. Yowei. 2014. Ethno-biological notes on the Meyah Tribe from the Northern Part of Manokwari, West Papua. J. Manusia & Lingkungan. 21 (1): 121-127.

Flanery, T.F. 1995. Mammals of The South-West Pacific and Moluccan Islands. Reed Book. Chastwood NSW 2067 Australia.

Iyai, D.A., A.G. Murwanto, A.M. Killian. 2011. Sistem perburuan dan ethnozoology biawak (Famili Varanidae) oleh Suku Yaur pada Taman Nasional Laut Teluk Cenderawasih. Biota 16 (2). [Abstrak].

https://ojs.uajy.ac.id/ index.php/biota/article/view/110/129 [June 08, 2016]

Kwapena, N. 1984. Traditional conservation and utilization of wildlife in Papua New Guinea. The Environmentalist 4: 22-26 (Supplement

No. 7).

Keiluhu, H.J. 2013. Impact of Hunting on Victoria Crowned Piegon (Goura victoria: Columbidae) in the Rain Forest of Northern Papua,

Indonesia. Goettingen Cuvillier Verlag

Goettingen.

Kümpell, N.F., E.J. Milner-Gulland, J.M. Rowclife, G. Cowlishaw. 2008. Impact on un-hunting on diurnal primates in continental Equatorial Guinea. International Journal Primatology 29: 1065-1082.

Loen, A. 2016. Hindari kepunahan, Gubernur Papua Larang Burung Cenderawasih jadi hiasan kepala. http://tabloidjubi.com/2014/04/15/ hindari-kepunahan-gubernur-papua-larang-burung-cenderawasih-jadi-hiasan-kepala/ [ June 08, 2016]

Mack, A.L, P. West. 2005. Ten thousand tones of small animals: wildlife consumption in Papua New Guinea, a vital resource in need of management. Working Paper No. 61.Resource Management in Asia-Pacific.

Makabori, Y.Y. 2005. Pergeseran pola perlaku kepatuhan masyarakat pada norma adatnya, kasus pergeseran nilai igya ser hanjop pada masyarakat lokal di kawasan Cagar Alam Pegunungan Arfak Kabupaten Manokwari. (Master Thesis) Bogor, Indonesia. Sekolah Pasca Sarjana IPB.

Mansoben, J.R. 2005. Konservasi sumber daya alam Papua ditinjau dari aspek budaya. Anthropologi Papua 2 (4): 1-12.

Nasi, R., D. Brown., D. Wilkie, E. Bennett, Tutin, G. vanTol, T. Christophersen. 2008. Conservation and use of wildlife-based resources: the bushmeat crisis. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, and Center for International Forest Resarch (CIFOR). Bogor. Technical Series No. 33.

Novriyanti, Burhanuddin, M. Bismarck. 2014. Pola dan nilai lokal etnis dalam pemanfaatan satwa pada Orang Rimba Bukit Duabelas Provinsi Jambi. Jurnal Penelitian Hutan dan

Konservasi Alam 11 (3):209-313.

O’Brien, T.G., N.L. Winarni, F.M. Saanin, M.F. Kinnaird, P. Jepson. 1998. Distribution and conservation status of Bornean Peacockpheasant Polypectron schleiermacheri in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Bird

Conservation International 8 (4): 373-385

DOI 10.1017/S095ß270900002136.

O’Brien, T.G., M.F.Kinnaird. 1996. Changing

populations of birds and mammals in North Sulawesi. Oryx 30 (2):150-156

O’Brien, T.G., M.F. Kinnaird. 2000. Differential vulnerability of large birds and mammals to hunting in North Sulawesi, Indonesia and the outlook for the future. In: Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Forests, eds. J.G. Robinson and E.L. Bennett 199-213. New York. Columbia University Press.

Padmanaba, M., M. Boissiére, Ermayanti, H. Sumatri, R. Achdiawan. 2012. Pandangantentangperencanaandi Kabupaten Mamberamo Raya, Papua, Indonesia. Studikasus di Burmeso, Kwerba, Metaweja, Papasenadan Yoke (Collaborative outlook of spatial planning of Mamberamo Raya Regency, Papua, Indonesia-case study in Burmeso, Kwerba, Metaweja, Papasena and Yoke)). Center for International Forest Research. Bogor. Indonesia. Pp 82.

http://www.cifor.org/mla/download/publication/ Mamberamo_id_web.pdf [ October 4, 2012]

Pangau, M.Z., R. Noske. 2010. Wildlife hunting and bird trade in Northern Papua (Irian Jaya), Indonesia. In: EthnoOrnithology, Birds, indigenous peoples, Culture and society, eds. S. Tideman and A. Gosler. 73 – 85. Washington DC. Earthscan.

Pangau-Adam, M.Z., R. Noske, M. Muehlenberg 2012.

Wildmeat or bushmeat? subsistence hunting and commercial harvesting in Papua (West New Guinea) Indonesia. Human Ecology. DOI: 10.1007/S110745-012-9492-5. http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/

10.1007%2Fs10745-012-9492-5 [December 12, 2012]

Pattiselano, F., 2006. The Wildlife hunting in Papua. Biota 11 (1): 59-61. Http://www.papuaweb.org/dlib/

jr/pattiselano2006.pdf [ April 4, 2012]

Pattiselano, F.,2007. Perburuan kuskus (Phalangeridae) oleh Masyarakat Napan di Pulau Ratewi, Nabire, Papua. Jurnal Biodiversitas 8 (4): 27-28.

Pattiselano, F. 2008. Man-wildlife interaction understanding the concept of conservation ethics in Papua. Tiger Paper 35 (4):10-12. http://www.fao.org/

docprep/012/ak855e00.pd [ April, 2012]

Pattiselano, F., G. Mentansan. 2010. The practice of traditional wisdom in wildlife hunting by Maybrat Etnic group to support wildlife sustainability in Sorong Selatan Regency. Makara Sosial Humniora 14 (2): 75 – 82.

Pattiselano, F., A. Arobaya. 2013. Indigenous people and nature conservation:opinion.

http://www2.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/01/05/i ndigenous-people-and-nature-con-servation.html. [ January 7, 2013]

Pemerintah Republik Indonesia. 1999. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor. 7/1999. Tentang pengawetan dan

pemanfaatan satwa liar. Jakarta. Sekretariat Negara.

Pratt, T.K., B.M. Beehler. 2015. Bird of New Guinea. 2 Edition. Princeton University Press.Princeton.

Sheil, D., R.K. Puri, I. Basuki, M. Van Heist, M. Wan, N. Liswanti, Rukmiyati, M.A. Sardjono, I. Samsoedin, K. Sidiyasa, Chrisdanini, E. Permana, E.M. Angi, F. Gatzweiler, B. Johnson, A. Wijaya. 2004.

Mengeksplorasi keanekaragaman hayati, lingkungan dan pandangan masyarakat local mengenai berbagai lanskap hutan; metode-metode penilaian lanskap secara

multidisipliner (Exploring biological diversity, environment and local people’s perspectives: multidisciplinary landscape assessment methods). Bogor. CIFOR.

Supriatna, Y. 2008. Melestarikan Alam Indonesia.

Jakarta. Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Randrianandrianina, F.H., P.A. Racey, R.B. Jenkins. 2010. Hunting and consumption of mammals and birds by people in urban areas of Western Madagascar. Oryx 44 (3): 411-415

Wadley, R.L., C.J.P. Colfer. 2004. Sacred forest, hunting and conservation in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Human Ecology22 (3): 313-337

Wamebu, N. 2000.Pemetaan Partisipatif Multipihak: Wilayah Nambluong di Kabupaten Jayapura-Papua. http://www.jkpp.org/downloads/ 04.%20Papua.pdf ] Januari 17, 2013]

58

Discussion and feedback